The SS Petersburg (T-AOT-9101), a 56-year-old Chesapeake class tanker operated by U.S. Maritime Administration, put to sea as part of a month-long exercise to demonstrate amphibious logistical capabilities that can be put to use in the Arctic environment. Arctic Expeditionary Capabilities Exercise (AECE) 2019 is mainly taking place in and around Alaska, including the Aleutian Islands, but elements of it are also being executed much further south. In SS Petersburg’s case, it left its mooring in Suisun Bay off Benicia, California, to exercise its core mission set—that being moving huge quantities of fuel from sea to shore—off of Coronado, California as part of the exercise. Exactly how it goes about doing this is pretty bizarre and looks even stranger to the average landlubber, to say the least.

The antique ship uses a massive device called a Single-Anchor Leg Mooring (SALM) buoy to work as a nexus of sorts that conveys fuel from ship all the way to the shore. The system’s barge-like apparatus sinks to the seafloor while leaving a buoy on the surface connecting it to the ship. Lines then carry large quantities of fuel from the ship to the barge and then to a weighted conduit that extends out all the way to shore—up to four miles away—laying along the bottom of the sea. That conduit ascends up the beach to a mobile receiving and distribution installation called a Beach Termination Unit (BTU) that is ferried ashore. The SALM can support up to four tankers offloading their fuel at once.

At first glance, it’s an odd and complex system, but it’s also effective and well-proven. Similar counterparts exist in the commercial world, as well. Petersburg can move a staggering 1,200,000 gallons of refined petroleum to an austere beachhead in a single day. But before the SALM can be put to work and the ship’s 225,000 barrels of fuel—as well as fuel from other tankers—can be sent ashore persistently, the huge SALM barge has to get from the ship’s deck into the ocean. That’s where the whole listing maneuver comes in to play.

The ship is built to be able to trim itself to list up to 15 degrees to port so that the SALM barge and buoy system can be shifted from its tilting deck platform into the ocean. The whole affair is bizarre if not downright unnerving looking:

Petersburg is one of five Offshore Petroleum Discharge System (OPDS) tankers that were built in the late 1950s and early 1960s that eventually found themselves assigned to the Ready Reserve Force. The tiny fleet was divided between three classes. Today, SS Petersburg is the last of the OPDSs, with her sistership SS Chesapeake, having been taken out of service in 2009.

The USMC currently relies on a number of methods for moving vast amounts of fuel from ship to shore. Remember that without gas, the modern Corps can’t fight and all of its vehicles and generator-dependent systems require copious amounts of fuel on a daily basis. A single new commercial ship under Military Sealift Command’s control, the MV Vice Adm. K.R. Wheeler, was introduced in 2007 to accomplish a similar role as SS Petersburg, but it is not a tanker and relies on other vessels to supply the fuel, acting as a node for transferring it from their holds to shore.

The Marines also leverage Navy LCAC hovercraft and landing ships to move fuel bladders and tanks ashore. The Navy’s new Expeditionary Transfer Docks will also come in handy for quickly transferring gas to the beach as needed. For higher volume, sustained operations, the Amphibious Bulk Liquid Transfer System (ABLTS) is used. It’s a far more modular and adaptable system—it can also pump fresh water—than what the SS Petersburg represents, but it isn’t as powerful and doesn’t have as long of a reach. It can be installed on different ships and can be rapidly deployed around the globe as required.

Still, even with these newer capabilities, as it sits now, the SS Petersburg’s combined tanker and fuel transfer capabilities are unique and will cease to exist within the Pentagon’s portfolio when she is finally retired sometime in the future. The Marines have posited other concepts to replace some of this capability and to augment the capabilities they already have, but no firm plans for the Pentagon to procure additional dedicated vessels, and especially anything like the Petersburg, appear to be in place at this time.

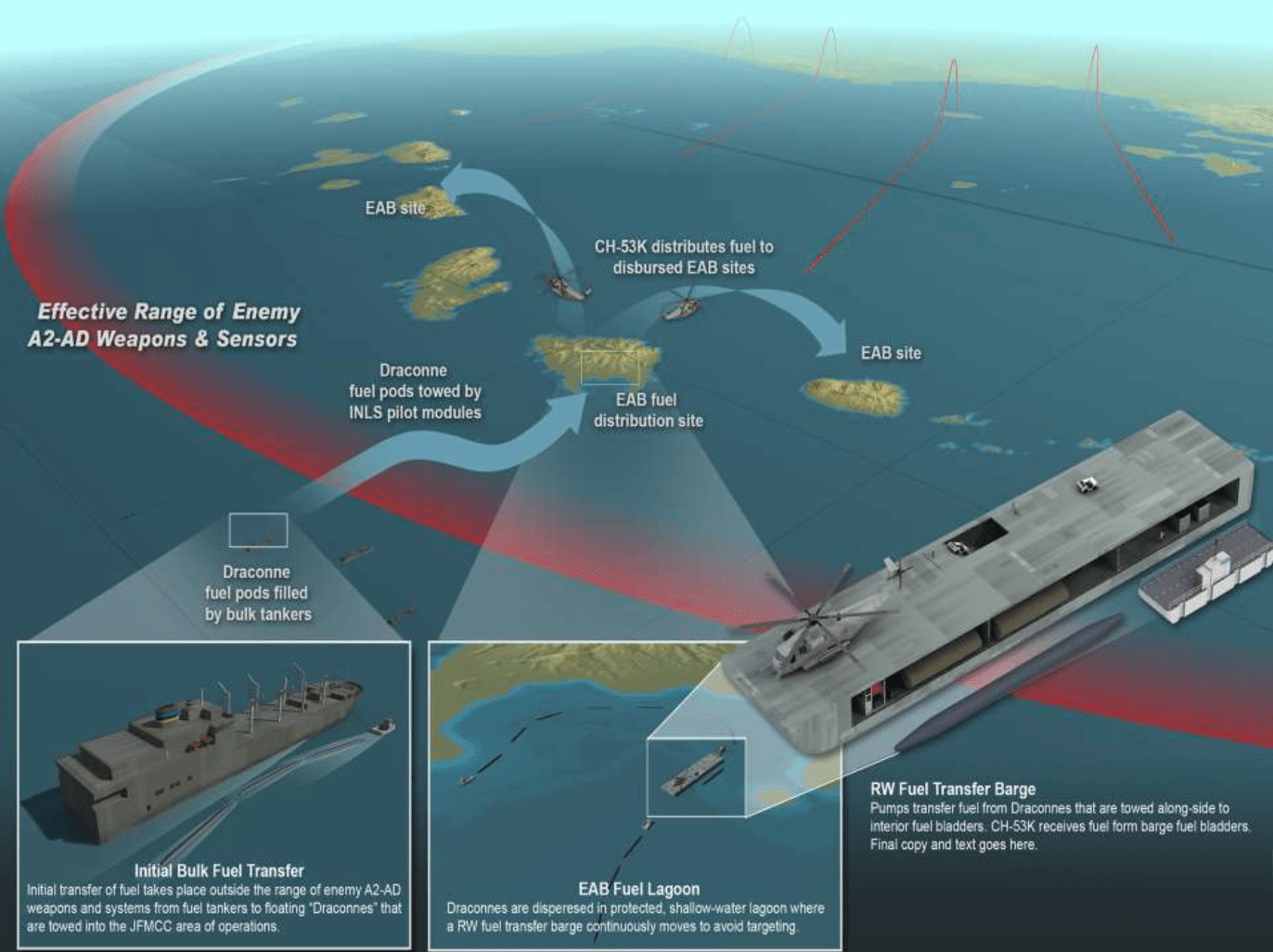

In many ways, SS Petersburg is a relic of times that may have finally passed us by—an age when massive beach landings were still seen as a highly plausible eventuality in a time of war. Fast forward to today and even smaller beach landings are becoming far less plausible. In fact, after years of debate, those at the top of the USMC’s power structure are admitting this and redesigning their procurement and combat strategies to focus less on amphibious landing operations and more on distributed forms of warfare across the maritime environment. You can read all about this new and controversial initiative in this past feature of ours.

Regardless of the highly questionable possibility of huge amphibious landings in the future, the need to move fuel from sea to shore without elaborate dock and transfer facilities hasn’t and won’t go away. In fact, the ability to do so more flexibly and numerously with smaller vessels and teams will likely define such a capability going forward, and not just for combat operations, but also for disaster relief and other contingency operations.

But until the Kennedy-era SS Petersburg pumps her last gallon, in the event that gobs of fuel are needing to be transferred from the sea to the beach, it’s still among the very best ships, if not the best ship for the job—even though it looks like it is about to sink while doing it.