The Pentagon says that a replacement for the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter’s long-troubled cloud-based computer brain is finally coming. The U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy have said that the existing system is one of, if not the most significant factor in the abysmal mission capable rates for their respective F-35 variants and a major contributor to the growing sustainment costs for the aircraft. Unfortunately, the upgraded system is not expected to be in widespread use until 2022 at the earliest.

Bloomberg was first to report that Ellen Lord, the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisitions and Sustainment, had revealed the existence of a replacement in the works for the F-35’s existing Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), on Jan. 14, 2020. Lord had talked to reporters about the new Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN) after leaving a Congressional hearing on the F-35 that was not open to the public. ODIN is a forced acronym that Lord said was a reference to the Norse god of the same name, according to Bloomberg.

The Pentagon is developing ODIN “with the voice of the maintainer and the pilots at the forefront of the requirements list,” Lord later told Reuters. “We have heard our maintainers on the flight lines loud and clear when they say they want to spend less time on administrative maintenance on ALIS.”

Despite often being described as the computer brain inside the F-35, ALIS is a much broader system that encompasses physical components on the aircraft and on the ground, as well as the cloud-based network backend that links them all together. The Joint Strike Fighter’s manufacturer, Lockheed Martin, which also developed ALIS for the U.S. military, has described it in the past as akin to a “smartphone” that is responsible for running “more than 65 applications that do everything from managing operations and training to maintenance and supply chain.”

Maintenance personnel definitely do use ALIS to collect information about the “health” of individual aircraft in order to perform various day-to-day tasks, such as isolating potential problems and order spare parts from the depot. It’s how Lockheed Martin sends out software updates for the F-35’s various systems, as well.

However, the system also serves as the upload and download point for operational data packages for the aircraft, which includes planning information such as the location of potential threats and general routes to and from mission areas. After a sortie, ground crews can then extract that information, plus additional data gathered from the F-35’s powerful sensor suite, for debriefing purposes and to support planning for future operations. You can read more about how all this works in detail in this past War Zone piece.

The Joint Strike Fighter’s manufacturer, Lockheed Martin, which also developed ALIS for the U.S. military, has long billed the system as helping to streamline maintenance and other operational activities. In principle, the networked system should allow personnel to more readily spot problematic maintenance trends and rapidly exchange important mission data between units.

In principle, ALIS has done anything but make the lives of personnel assigned to Air Force F-35 units, especially their maintenance, easier. “I can guarantee that no Air Force maintainer will ever name their daughter Alice,” then-Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson said during a public talk at a conference in February 2019.

After years of work and billions of dollars to try to fix its underlying software, ALIS has remained a broken mess that is difficult to use and often displays information that is flat out wrong, leaving maintenance personnel struggling to diagnose problems and wasting time ordering the wrong parts or mistakenly sending perfectly serviceable components back to the depot. On top of that, the system has to contend with the fact that not all F-35s are configured the same way as a product of a concept known as concurrency, wherein Lockheed Martin started building aircraft with the idea that upgrades and fixes would be added into the jets during depot maintenance down the line.

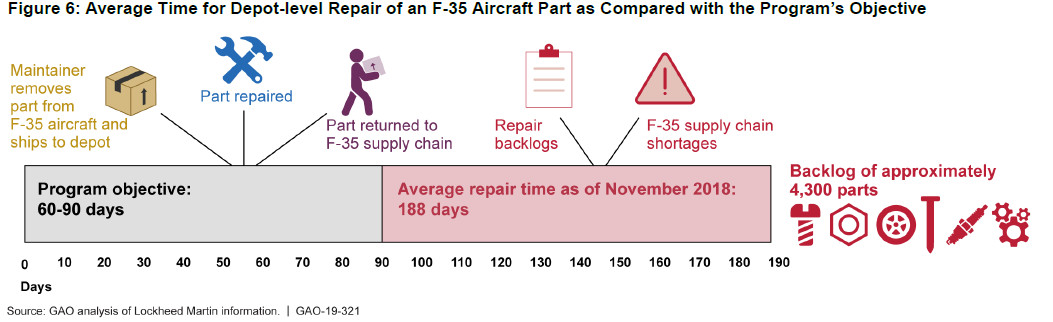

So, for example, as of April 2019, it took 188 days on average for depot-level repair of F-35 parts, more than twice as long as the Pentagon’s desired maximum timeframe, in large part because of issues with ALIS, according to the Government Accountability Office. General parts shortages and cascading maintenance backlogs have only exacerbated the issue.

In 2018, U.S. Air Force training units at Eglin and Luke Air Forces Bases simply stopped using ALIS altogether, relying on separate databases instead, because of these and other problems. These issues with ALIS have also, in turn, contributed to extremely low availability rates for F-35s across all the services.

ALIS has also posed nagging cybersecurity and operational security risks, the latter of which has led some foreign Joint Strike Fighter partners to develop their own firewalls to limit how much data they exchange with it.

As then-Air Force Secretary Wilson’s remarks last year made clear, these issues are very well-known. The month before she publicly quipped about how much maintainers hate ALIS, the Air Force had announced that it had begun development of a replacement under a program called Mad Hatter. It’s unclear whether or not this is related to the new ODIN effort that Undersecretary of Defense Lord says is also now in progress. It’s also not clear how much ODIN leverages from ALIS and how closely related the two systems might be, despite the name change.

“The goal [of Mad Hatter] is not simply to fix ALIS within the constraints that define it,” Will Roper, the Air Force’s top acquisition official, had told Defense News regarding that program, in February 2019. “It is to make the operator – the maintainer – more efficient, to make their user experience more pleasant.”

Beyond that, it remains to be seen when ODIN might produce any real results and when an upgraded system might actually find its way to actual F-35 units. Lord told Reuters that she only expected the new computer system to be available to all Joint Strike Fighter units across the U.S. military by 2022, if everything goes to plan. Representative John Garamendi, a California Democrat who chairs the House Armed Services Committee’s Readiness Subcommittee, which held the recent hearing on the F-35, also told Reuters he felt that the Pentagon was working on “a very tight time frame.”

Lord also added that deployable versions of the system would not be ready in 2022. This means that it’s unclear when forward-deployed F-35 units and Marine and Navy Joint Strike Fighters operating from amphibious warfare ships and aircraft carriers will actually start using ODIN and how this might impact their operations. The Marines and Navy are already facing issues due to the fact that various stocks of spare parts the services had previously purchased to support afloat operations are no longer usable in the more current configurations of their respective F-35B and C aircraft, another byproduct of concurrency.

If there’s any silver lining to the present situation, F-35 units have already demonstrated that workarounds are available, if time-consuming. This could actually be valuable experience for conducting operations in instances where ALIS, or the future ODIN replacement, are suddenly unavailable for any reason.

All told, the Pentagon, as well as the Air Force, Marines, and, Navy, are clearly eager to put the ALIS saga behind them. Unfortunately, any improvements still appear to be years away, leaving F-35 units stuck with ALIS, or convoluted workarounds using other systems, in the meantime.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com