A few days ago, U.S. Navy Landing Craft Air Cushions, or LCACs, roared onto Sunset Beach in Warrenton, Oregon and across the sand at Oak Harbor, Washington, offloading trucks, construction equipment, and other cargo, as well as Sailors, Marines, and other personnel. But the force wasn’t conducting a mock amphibious assault. It was training to respond to a potential natural disaster that could, and by most predictions would, be on a scale the United States hasn’t seen in modern times—a major Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake event, often referred to as “the big one.”

The paired training exercises, which focused on what is officially known as the Defense Support to Civil Authorities (DSCA) mission, occurred on June 3, 2019. Pictures and video show the two hovercraft LCACs leaving the well deck of the San Antonio-class landing platform dock amphibious ship USS Anchorage and bringing ashore various vehicles, including Marine Corps 5-ton Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacement (MTVR) trucks, pickups, and front end loaders. Members of the Navy’s Beachmaster Unit One (BMU-1), based at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado in California, were on hand to manage activities on the beach and direct the landing craft to and from their assigned drop off points.

“These training evolutions are a great way to showcase the Navy-Marine Corps team’s capability of bringing help to those in need after a natural disaster,” U.S. Navy Captain Dennis Jacko, the commanding officer of the Anchorage, said in a statement. “Exercises and training like this helps prepare our Sailors and local government agencies to work together seemlessly so that in the event of an earthquake or tsunami, we are ready to help in any capacity required. Amphibious ships are a key component of this capability, with tremendous cargo and medical facilities that are flexible enough to provide support anywhere along the coast.”

The exercise also involved elements of the Oregon National Guard and Clatsop County Emergency Management. In conjunction with the DSCA exercises on the beaches, the Oregon Air National Guard also conducted an exercise called Cascadia Airlift, involving the movement of vehicles, cargo, and personnel via a C-130 Hercules transport aircraft, also as part of a mock disaster relief mission. The C-130 flew low over the Oregon beach as part of a mock airdrop, as well.

But when it comes to landing on beaches, the LCACs offer significant benefits over traditional shallow-draft boat-type landing craft, including better speed and “over the beach” mobility. Hovercrafts, in general, can also cross very shallow water and conduct operations on soft ground, such as marshes and swamps, which also helps them get into areas that may be inaccessible to other boats. Most importantly, they can access totally unimproved beaches and rapidly deliver massive loads ashore—something that would be absolutely critical if the big one hit the Pacific Northwest.

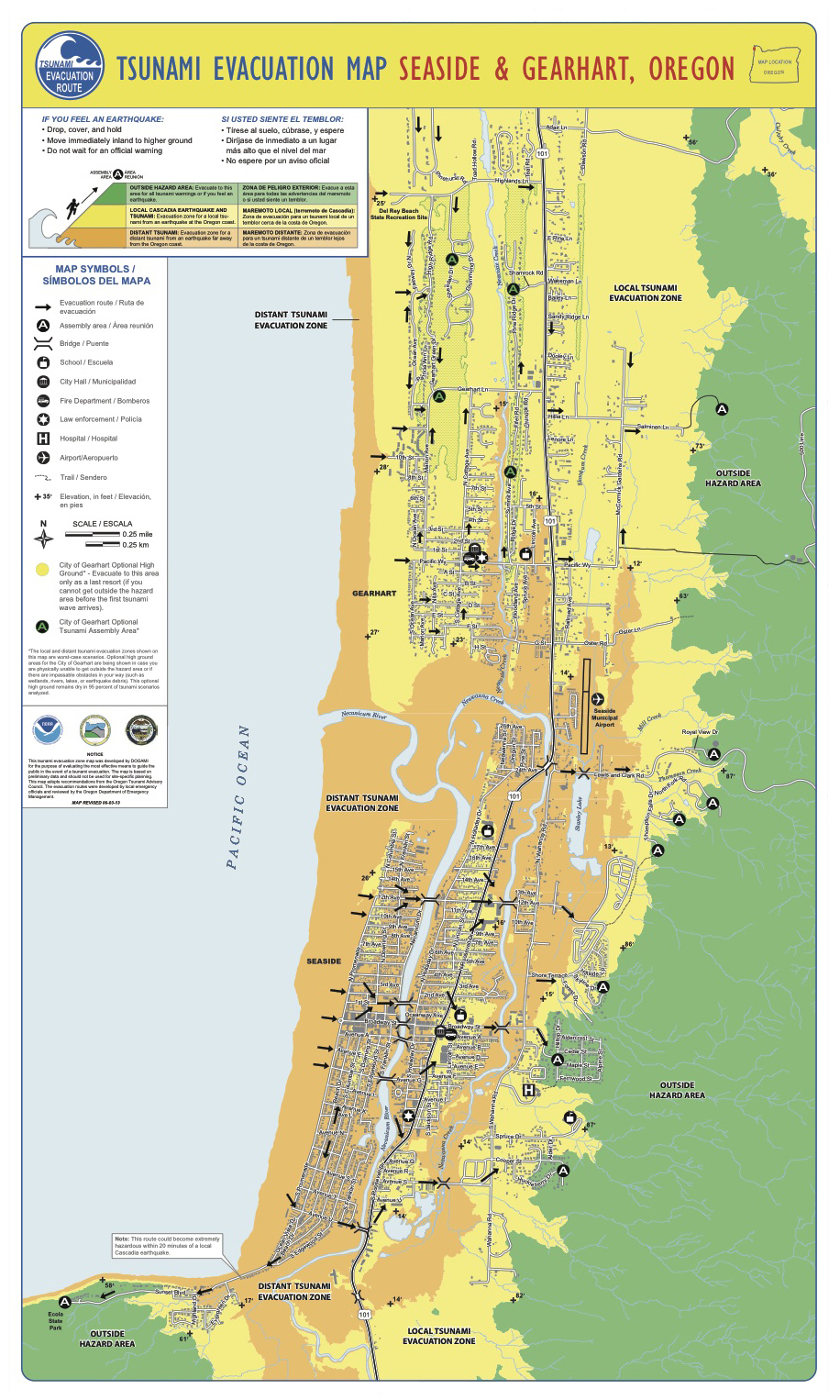

Within minutes of a major movement along the Juan de Fuca and Pacific tectonic plates, a massive tsunami would come roaring ashore across huge stretches of Oregon and Washington coastline. The small beach towns already devastated by the powerful quake that would measure around a nine on the Richter Scale would be slammed with a massive wall of water rising up to 100 feet high.

The level of destruction we are talking about here in small communities with limited resources is largely unfathomable. Roads that snake through the coastal mountain ranges will be unpassable for days, weeks, and even months. Bridges and overpasses will be dropped all over the states and especially along and near the coast. Channels will be unpassable and docks will be destroyed. This leaves few options for evacuating citizens and conveying absolutely essential supplies in large quantities to devastated coastal locales. The Navy’s mighty LCACs and the amphibious ships that tote them around are Oregon and Washington’s best potential lifeline during what would be both states’ darkest hour.

This is largely what’s behind these exercises. The region is well overdue for this horrible event and predictions keep getting worse as to what it will actually look like when it occurs as well as its protracted aftermath. So, seeing the military getting serious about the reality that this emergency call will come sometime in the future and only it really has the capacity to make large-scale and rapid impacts when it comes to saving lives and beginning a recovery effort that will take place over a huge stretch of territory where infrastructure will be completely obliterated, is very much a good thing. In fact, it’s baffling that the LCACs haven’t arrived on Oregon and Washington shores for this type of training years ago.

As for the LCAC itself, the Navy first began using the LCAC in 1986. The service has been slowly putting the hovercrafts through a Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) since 2001. As of December 2018, 64 had gone through the SLEP process, which involves a major structural overhaul, improved corrosion resistance, upgraded engines for more reliable operation in very hot weather, and improved communications, navigation, and other mission systems. Eight more of the hovercrafts still needed the update.

Able to carry up to 75 tons of cargo if necessary and capable of reaching speeds of more than 40 knots, or over 45 miles per hour, LCACs can readily bring vehicles, heavy equipment, and supplies into affected areas even if traditional port facilities are not operational. Depending on the exact terrain, they can also try to bring those cargoes closer to the desired destination, bypassing roads and bridges that may be impassable.

The video below offers a good look at the LCAC’s general capabilities.

Though LCACs are primarily intended to support amphibious assault missions, these same attributes have repeatedly proven to be valuable in responding to natural disasters in coastal areas over the years. LCACs notably took part in the response to Hurricane Katrina along the Gulf Coast in 2005.

To keep these skill sets fresh for LCAC crews and other adjacent units and personnel, such as the Navy’s Beachmasters, as well as to help appraise federal, state, and local officials as to the hovercraft’s capabilities, they routinely take part in DSCA exercises.

In 2017, Anchorage actually conducted a similar exercise in the Pacific Northwest, but with boat-type landing craft rather than LCACs, in and around Newport, Oregon and Grays Harbor, Washington. This exercise also involved U.S. Army UH-60 Black Hawk and CH-47 Chinook helicopters, which flew to and from the ship. During disaster response missions, helicopters have also shown themselves to be an essential asset for moving equipment, supplies, and personnel ashore, as well as rescuing civilians or otherwise providing an immediate response to medical and other crises.

Amphibious ships with LCACs and other landing craft, as well as helicopters, would be essential when it comes to responding to a disaster like the big one, but just getting all of the necessary assets into position could be extremely time-consuming. That is why training for this specific event is so key. Hopefully doing so will cut down the time it takes to initiative such deployments on a sudden basis and such a large scale.

The value of LCACs in a disaster relief scenario isn’t limited to the West Coast, though. There are equal fears that serious disasters might ravage the East Coast. Hurricane Sandy in 2012 exposed a host of issues in preparations to respond to major disasters in the Northeastern United States. Since 2017, Hurricanes Harvey, Maria, and Michael have also underscored the threat to the Gulf Coast region from increasingly extreme weather, which many scientists have linked to global climate change.

The U.S. military is already coming to terms with these issues, and their connections to global climate change, but even in the best case scenarios, it may not be possible to stave off an uptick in all sort of severe weather in the near-term, including flooding and tornadoes. The various branches may find it more and more important to be training for disaster relief missions, and with an eye toward the homeland, rather than the more traditional focus of being prepared to respond to humanitarian emergencies overseas.

At the same time, the Navy is in the process of replacing its aging LCACs altogether with a new, improved hovercraft, known as the Ship-to-Shore Connector (SSC). Unfortunately, this program has suffered a number of delays due to technical problems with the design since development began in 2009. The service now expects to take delivery of the first SSC in July 2019, some two years behind schedule, though it still hopes to declare initial operational capability with the improved hovercrafts in 2020.

Until the SSCs reach full operational capability, which is still years away at best, the LCACs will continue to serve as a means of getting troops ashore during amphibious operations and as a tool for responding to natural disasters at home, as well as abroad. If the big one does hit and the large parts of Pacific Northwest coastline lay in ruin, the arrival of these amazing machines will equal local survivors’ most desperate wishes coming true.

Contact the authors: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com and tyler@thedrive.com