Japan has the ability to shoot down an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) like the Hwasong-12 fired off by North Korea on Oct. 4th and flew over Japan, prompting warnings for people to seek shelter and temporarily halted trains. Yet, the powers that be in Tokyo opted not to. Here’s why.

It is one thing to have the capability to intercept an incoming IRBM. But actually firing an interceptor at one launched by North Korea, something that has never happened, raises a lot of issues, David Shank, a retired Army colonel and former commandant of the Army Air Defense Artillery School at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, told The War Zone Tuesday morning.

“In my opinion, there is no reason to engage a ballistic missile if it’s going to land in the Pacific Ocean,” said Shank, who has co-authored papers for the National Institute for Public Policy on missile defense.

Shank said that there are a wide array of space-, sea- and ground-based radars and other sensors that can quickly detect such a launch and determine its general trajectory and altitude.

The trajectory and altitude of a ballistic missile launch can be recognized “fairly quickly, within the first five minutes,” said Shank, with those radars and other sensors, powered by artificial intelligence, updating the track along the way.

Monday’s launch, which took place at 7:22 a.m. Tokyo time, lasted about 22 minutes, Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada told reporters.

It flew “about 4,600 km (almost 2,900 miles) at a maximum altitude of about 1,000 km (about 620 miles), and passed over Aomori Prefecture from about 7:28 a.m. to 7:29 a.m.,” he said. “Later, at around 7:44, it is estimated that it fell outside of Japan’s exclusive economic zone, about 3,200 km (nearly 2,000 miles) east of Japan.”

In this case, Japan did not engage the North Korean IRBM because the JSDF – using “various radars of the Self-Defense Forces” – confirmed it posed no risk of landing in Japan, Hamada said.

“Since we judged that there was no risk that the missile would come to our country, we did not take any measures to destroy the ballistic missile, based on Article 82-3 of the Self-Defense Forces Law.”

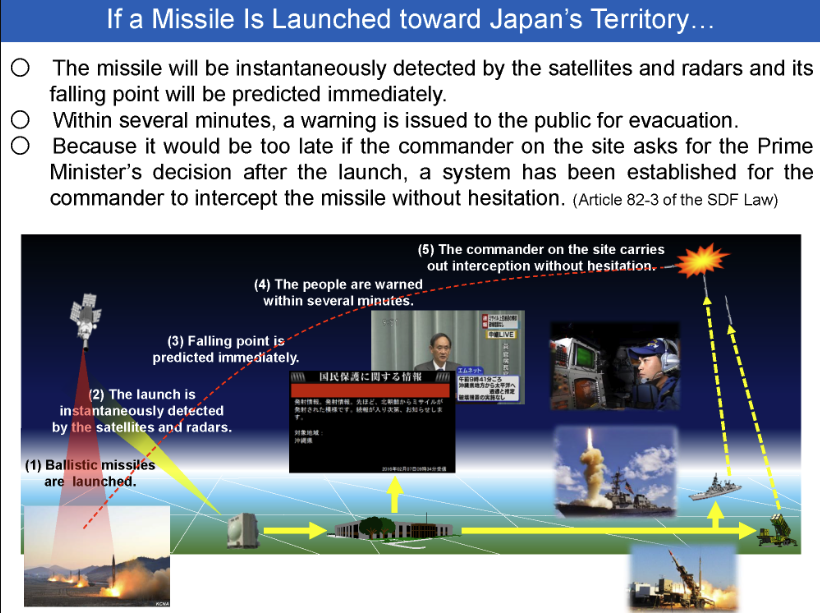

That law spells out how and when the JSDF can launch an intercept, with the recommendation of the defense minister and the approval of the prime minister.

Know When To Hold ‘Em

Shank gave four reasons for not wanting to fire an interceptor in a situation like Monday.

The first is that firing an intercept “could escalate the situation” when the landing point was somewhere in the Pacific Ocean.

The second is that “an engagement would demonstrate U.S. and Japanese capabilities (ie., early warning and when a system such as an Aegis cruiser or destroyer would engage a target).”

The third is that a miss could cause “great concern among Americans, the Japanese, other allies and partners around the world, and give North Korea the narrative momentum.”

The fourth “is that an engagement over a population center or other critical infrastructure” could cause damage “due to falling debris from an engagement.”

Japan has two ways of shooting down ballistic missiles. These include ship-based SM-3 interceptors capable of broad area defense via midcourse interception — while the missile is cruising towards its target at very high altitudes. The other is the Patriot (PAC-3 MSE) missile, which is capable of intercepting some ballistic missiles during the terminal stages of their flight as they descend toward their targets at very high speed.

Shank was far less optimistic about the effectiveness of the Patriot system when it comes to Japan’s missile defense arsenal.

“The SM-3, in this case, is the only capable system available to defeat an IRBM,” he said. The Patriot system “has a chance, but a very low probability of a kill.”

The Patriot is known to be better suited for intercepting shorter-range ballistic missiles during the final phase of their flight and does not feature the large area defensive capabilities as a midcourse interceptor like the SM-3.

“The SM-3 is responsible for midcourse defense and the Patriot PAC-3 for terminal defense,” Maj. Gen. Hiroyuki Sugai, the Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) attache in Washington D.C., told The War Zone. “Each covers a different area. Generally speaking, midcourse defense covers a large area, so Aegis ships can intercept a large area.”

Japan Remains Confident

The Japan Self Defense Forces (JSDF) is “confident in our efforts” to “intercept” an IRBM like the nuclear-capable Hwasong-12, Sugai told The War Zone Tuesday morning.

The Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) Interceptor gives Japan the ability to defend against exactly these kinds of attacks and updates to the type’s design bring even more capabilities.

The SM-3 interceptors are enabled by ballistic missile defense-capable baselines of the Aegis Weapon System, using a hit-to-kill kinetic kill vehicle.

Currently, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, or JMSDF, Aegis fleet comprises two Maya class, two Atago class, and four Kongō class destroyers. The latest Maya class warships are subvariants of the Atago class, which in turn evolved from the Kongō class, a Japanese derivative of the U.S. Navy’s Arleigh Burke class destroyer.

Sugai would not comment on the operational status of the newer SM-3 Block IIA interceptors he said Japan began purchasing in 2017. They offer a wider engagement envelope than currently fielded SM-3 variants and are thus better able to tackle a wider range of missile threats. This missile is a joint development effort between the U.S. and Japan.

Japan had previously abandoned a land-based arrangement from which to deploy SM-3 interceptors.

Work on the planned pair of land-based Aegis Ashore systems was suspended in 2020, with officials citing amid technical issues, rising costs, and domestic criticism. The latter included concerns that debris from intercepted missiles could land on Japanese territory and cause damage or injury, which threatened to jeopardize testing of the missile portion of the system. There has also been significant public concern about the potential health impacts of the radiation from the Aegis Ashore system’s powerful radars.

Japan, meanwhile, is looking to boost its fleet of Aegis-equipped, ballistic missile defense-capable vessels.

It has plans to build two huge new warships. The as-yet-unnamed missile defense ships are expected to have a standard displacement of around 20,000 tons — more than twice as much as the current Aegis-equipped Maya class destroyers — making them potentially the biggest Japanese surface combatants since World War II. You can read much more about that here.

In addition to the Japanese systems, the U.S. deploys SM-3s aboard some Aegis-equipped destroyers and cruisers. The U.S. also maintains Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) systems in South Korea and Guam. This is also a terminal intercept system but with far great capabilities than Patriot and is uniquely suited to defend specific areas against IRBMs.

Muted Response

Neither the U.S. nor Japan launched an inceptor against the North Korean missile. But the U.S. and its allies, Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK) did take action in the wake of that launch.

On Wednesday, Korean Standard Time, the U.S. and South Korea “fired four ground-to-ground missiles into the East Sea on Wednesday in joint drills, a day after North Korea’s intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) launch,” the Yonhap News Agency reported, citing the South’s military.

“The two sides each launched two Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) missiles, which precisely hit mock targets and demonstrated the allies’ capability to deter further provocations,” Yonhap reported, citing the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff.

However, one of those missiles misfired, setting off explosions at the Gangneung Air Base.

A day before, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and ROK airmen conducted a joint exercise over the West Sea on Oct. 4 Korean Standard Time “to showcase combined deterrent and dynamic strike capabilities while demonstrating our nation’s bilateral interoperability. During the exercise, they conducted a live Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) strike” at a firing range on the uninhabited Jikdo Island.

In addition, U.S. Marine Corps F-35 Joint Strike Fighter jets joined Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) fighters in a bilateral exercise over the Sea of Japan on Oct. 4.

While both Japan and the U.S. claim they have the ability to intercept a North Korean IRBM, it’s never happened in a real-world launch and, as David Shank pointed out, there are many reasons to keep that powder dry. Missile defense is not the shield many perceive it to be either. Many things have to work perfectly for it to work and while testing has been persistent and encouraging in some ways, there are questions as to how well they would perform under real-world circumstances. This is especially true if multiple missiles were launched at a target at once. You can read more about this reality in this past feature of ours.

But at some point, there may come a time when a kinetic response is required in the wake of a missile launch and many believe denying North Korea these tests kinetically would be a key deterrent in keeping them from happening in the first place. This is especially true when it comes to sending missiles over Japan and the real dangers that are involved in such operations.

For now, it seems, like pretty much everything else related to the North Korean situation, Japan and the U.S. are locked into a status quo when it comes to attempting to intercept the Kim Regime’s ballistic missile tests.

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com