On March 6, 2017, the first elements of a U.S. Army Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) battery arrived in South Korea. While the deployment followed a series of North Korean missile launches, that latest provocation may have been in response to the imminent American plans, rather than vice versa, as the Pentagon implied in its announcements.

“Continued provocative actions by North Korea, to include yesterday’s launch of multiple missiles, only confirm the prudence of our alliance decision last year to deploy THAAD to South Korea,” U.S. Navy Adm. Harry Harris, head of U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM), said in a statement. “We will resolutely honor our alliance commitments to South Korea and stand ready to defend ourselves, the American homeland, and our allies.”

Sending THAAD to the Korean Peninsula has long been controversial. In addition to North Korea’s accusations of more Western aggression, Chinese officials repeatedly argued the missile battery could be aimed at their country’s nuclear deterrent. South Korea protesters worried the unit could make them priority targets or pollute the environment. South Korean conglomerate Lotte Group ultimately agreed to host the battery at a remote, defunct golf course to allay those concerns.

But beyond all of these political issues, there is a much bigger one lurking: does THAAD even work? Most notably, the system still has yet to prove it can take down a surrogate for missiles like North Korea’s worrisome Musudan. Pyongyang’s troops first successfully tested that missile in June 2016. Since long-time leader Kim Jong Il died in 2011 and his son Kim Jong Un took over, the reclusive country has been steadily and publicly expanding and improving its ballistic missile arsenal in general.

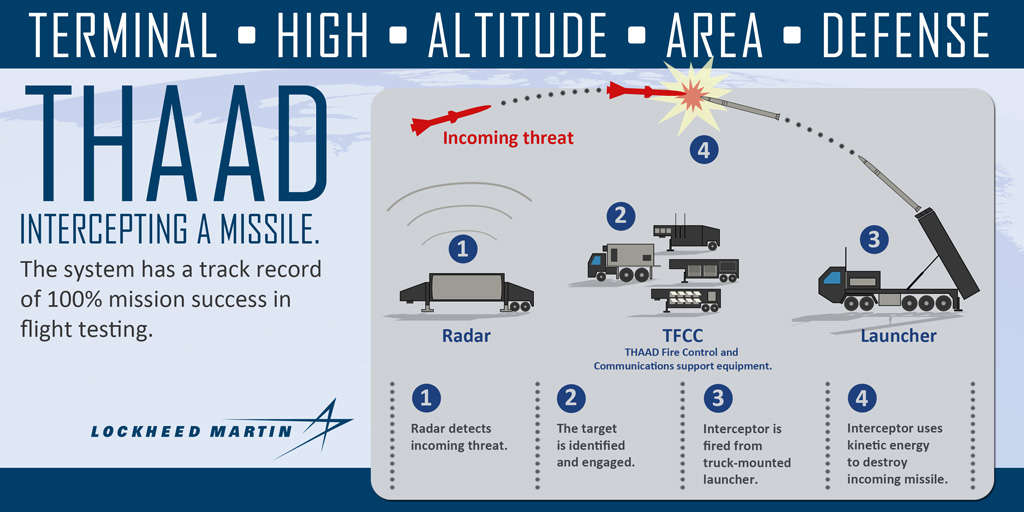

In theory, the THAAD works by detecting incoming ballistic missiles and then firing interceptors to destroy them high above, and well before they hit the ground. Tracking a fast-flying projectile with powerful radars, such as the trailer-mounted AN/TPY-2 or the floating Sea-Based X-Band (SBX) and then knocking it out of the sky is a complicated procedure even when everything is working properly. As of January 2017, a complete THAAD battery included the missiles in their wheeled launchers, an AN/TPY-2, fire control equipment and other supporting gear.

In active development since the 1990s, the THAAD program has suffered repeated delays, quality control issues and other problems. Defense contractor Lockheed Martin kicked off the first flight tests kicked in April 1995. THAAD did not successfully hit a target of any kind until its 10th test in June 1999.

A year later, the Pentagon gave Lockheed Martin a new contract to start the engineering and manufacturing development of the system. Engineers did not test fire the refined system until November 2005. Part of that delay had been beyond the Maryland-headquartered defense contractor’s control. The firm had subcontracted work on the rocket motors to Pratt and Whitney’s space propulsion division.

Between August and September 2003, explosions at Pratt and Whitney’s production complex in San Jose California killed one employee, caused significant damage and physically rattled the surrounding community. Lockheed Martin scrambled to find someone else to make THAAD motors and Pratt and Whitney ultimately closed the accident-prone plant.

It wasn’t until 2012 that THAAD managed to shoot down a mock medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM). The weapon has repeated that feat multiple times since. However, as of December 2016, the system had still not proven it could shoot down an intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) surrogate, according to the Pentagon’s Office of the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation’s (DOT&E) annual report.

In commonly accepted terms, an MRBM has a range of between approximately 1,000 kilometers (just over 620 miles) and 3,000 kilometers (under 1,870 miles), while an IRBM can hit targets nearly twice as far away. Many experts believe North Korea’s Musudan, also referred to as the BM-25 or Hwasong-10, is in the IRBM category.

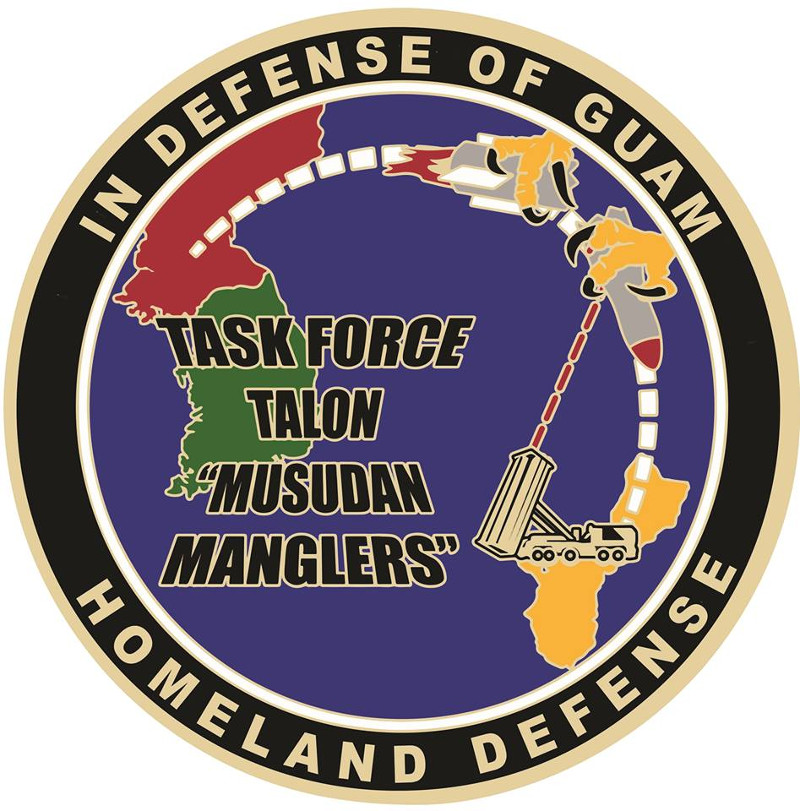

When Army missile defenders touched down with THAAD on Guam in 2013, they adopted the nickname “Musudan Manglers.” Unfortunately, there is no definitive proof at this point THAAD can actually defeat all the North Korean missiles the Pentagon cites as the reason for its deployment South Korea in the first place. Even more problematic, the Pentagon has not yet deemed the missiles suitable for general service.

“The THAAD program continued work on achieving a Full Materiel Release of the first two THAAD batteries,” DOT&E’s routine review added. These units “achieved Conditional Materiel Release in February 2012.”

The Pentagon agreed to that conditional release in order to get the missiles to Guam. In its 2013 review, DOT&E said the system had only a “fundamental capability” and that there were still more than 30 significant problems for Lockheed Martin to fix. Sending THAAD out into the Pacific in that state had been “better safe than sorry, better something than nothing,” John Pike, director of GlobalSecurity.org, told Foreign Policy in April 2013.

The concerns do not appear to have been entirely unwarranted. In 2015, the Army quietly replaced all of the THAAD missiles on Guam with new ones to “maintain operational readiness.” The service touted the operation as a major feat of logistics, but offered no details as to why it needed the replacements.

To be fair, none of this proves THAAD can’t do its job. The system has steadily improved its record over the decades, continuing to knock down targets in tests. In 2016, the missiles smashed a short range ballistic missile (SRBM) surrogate and an MRBM-type target near simultaneously during a flight test in the Pacific Ocean near Wake Island.

The program’s engineers plan to try and hit a mock IRBM for the first time during the 2017 fiscal year. In 2018, they want to try and test the system in conjunction with a Patriot missile battery. In December 2016, DOT&E said only four of its original 39 recommendations remained unresolved.

Of course, if and when Lockheed works all the kinks out of THAAD, the system will still has significant limitations. For the interceptors to be truly effective, commanders have to position the launchers near potential targets, along likely flight paths, pointed opposite where the warheads might fall. Based on publicly available information, the weapon can only pinpoint and fire at targets in an 120-degree cone and over a finite range. Not just that, but THAAD has not been thoroughly tested or lacks engagement capability against targets that fly extreme apogee flight profiles, a tactic North Korea could use to hit targets in Seoul and military bases not too far south of the DMZ.

Even if the battery is situated properly, that might not be enough. The single THAAD battery in South Korea has just two launchers, each with eight interceptors at the ready. In any realistic future attack scenario, North Korea would launch dozens of missiles or more at targets across the southern portion of the peninsula and potentially beyond, using both road-mobile weapons, and in the not so distant future, even ballistic missiles launched by submarines. Those submarines will also likely voyage outside of THAAD’s engagement envelope before launch.

Both of these launch methods are very hard to track, often alerting U.S. early warning satellites only as the missiles take flight, leaving little time for missile defenders to reorient themselves towards the threat. American and allied forces would need dozens of launchers and a constantly active constellation of space, surface and ground-based sensors spread across East Asia to have a reasonable chance at not getting overwhelmed by the ensuing barrage.

So far, the Army has never fired a THAAD in anger against a real threat. Hopefully, the troops in South Korea won’t need to respond to an attack before they know exactly what the missiles can do and have them in the right places.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com