The news hit this weekend that the Carl Vinson Carrier Strike Group, which was visiting Singapore and slated to move south to Australia, has been ordered north, toward the Korean Peninsula. The order came as President Trump wrapped up his first state visit with Chinese President Xi Jinping, during which North Korea was supposedly a top topic for discussion.

The White House had increasingly made it clear that it is prepared to “deal with” North Korea and their ballistic missile and nuclear programs alone if China will not help out. Another ballistic missile test launch just last week seems to have accelerated this initiative, and a possible major missile or nuclear test on April 15th—the locally cherished birthday of Kim Il Sung—would only put more pressure on the Trump regime to act in some way. This all comes as it has been widely reported that Trump’s national security team has wrapped up a review of options for taking on the Kim regime.

These options have ranged from enacting even more invasive sanctions on Pyongyang, to changes in strategic posture, to direct military actions. The changes in strategic posture options in particular seem to include forward deploying tactical nuclear weapons to South Korea—something that has not occurred since 1991—and would require the approval of the South Korean government. It is uncertain if such a plan would be possible to achieve seeing as one of South Korea’s Presidential candidates, Moon Jae-in, looks to take a far less iron-fisted approach with North Korea than his ousted predecessor, and would even put the deployment of the American THAAD anti-ballistic missile defense system up for review. The other front runner candidate, Ahn Cheol-soo, looks to increase South Korea’s hardline approach toward its pesky neighbor to the north.

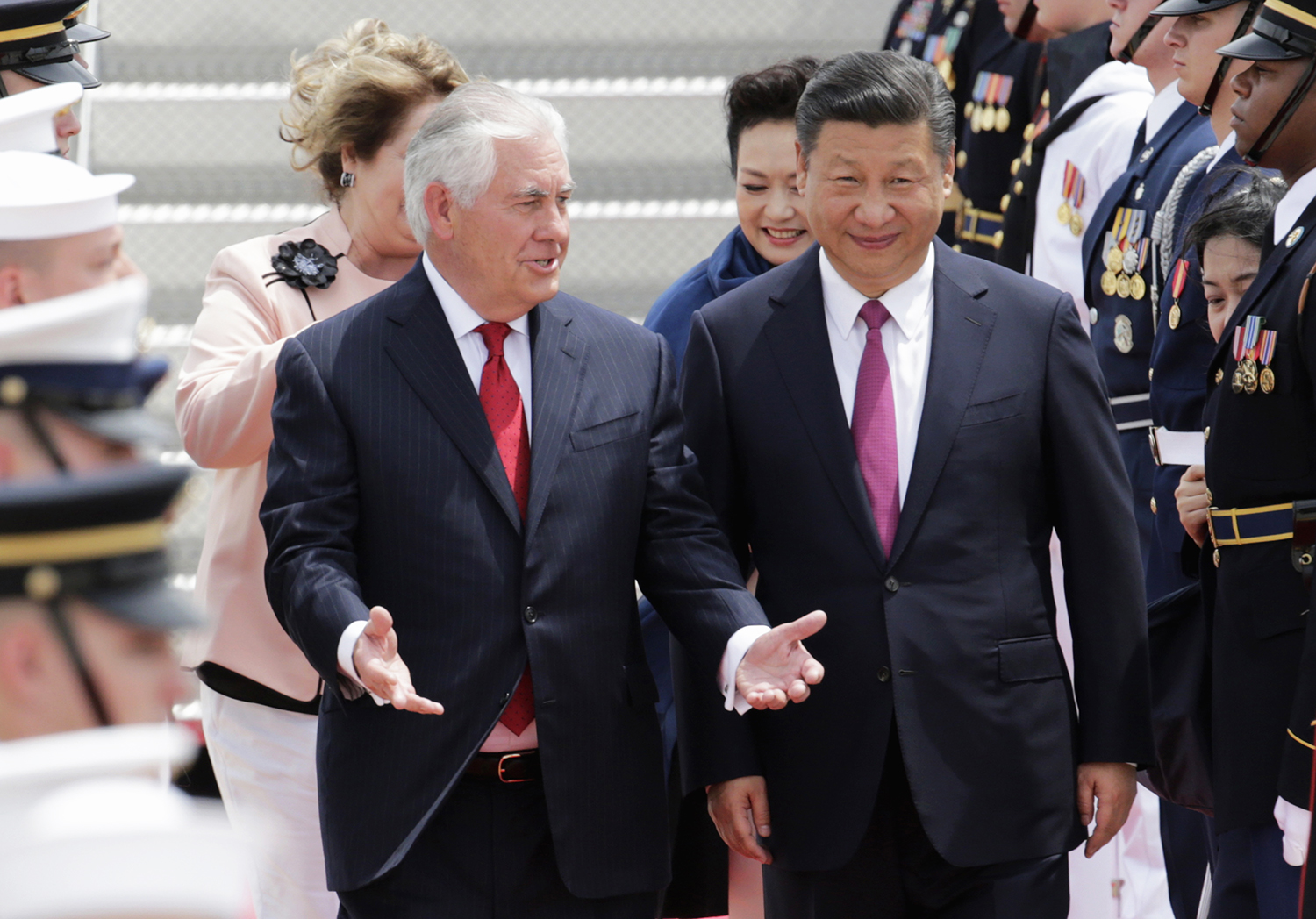

Aside from longer-term strategic options and possibilities, there is real concern that some sort of military action or showdown will occur once the USS Carl Vinson and her flotilla arrive in the waters off the Peninsula. In recent weeks, there have been somewhat vague indications that have pointed toward something like that being in the works, so it is not just the fact that the Navy has suddenly ordered a carrier to head in that direction that is causing anxiety about what’s to come. In fact, the Carl Vinson recently left South Korean waters after partaking in large scale exercises over and around the Peninsula. Just last week Trump made it clear that “if China is not going to solve North Korea, we will.” And this weekend, the meeting with Xi Jinping didn’t seem to result in some overwhelming breakthrough in cooperation, yet alone an agreement on a firm plan between Washington and Beijing on the issue. Still, it seems China was willing to put a bit more pressure on North Korea than before. This morning Secretary of State Rex Tillerson stated:

“President Xi clearly understands, and I think agrees, that the situation has intensified and has reached a certain level of threat that action has to be taken… We’re hopeful that we can work together with the Chinese to change the conditions in the minds of the DPRK leadership. And then, at that point, perhaps discussions may be useful… But I think there’s a shared view and no disagreement as to how dangerous the situation has become. And I think even China is beginning to recognize that this presents a threat to even to China’s interests as well.”

There was also this Tillerson quote from his trip to South Korea:

“Let me be very clear: the policy of strategic patience has ended. If they [North Korea] elevate the threat of their weapons program to a level that we believe requires action, that option is on the table.”

Then this short but ominous statement from Tillerson following North Korea’s latest missile launch:

“North Korea launched yet another intermediate range ballistic missile. The United States has spoken enough about North Korea. We have no further comment.”

So we are left with a bit of a mixed bag as to understanding exactly what comes next. But above all else, Thursday’s token attack on Syria’s Shayrat Air Base has led many to think that the President may be more open to grabbing for the military option in the near term than as a last resort when it comes to North Korea. The reality is that the missile attack did no real damage to Assad’s war fighting machine—in fact it strengthened it drastically—nor did it threaten Assad himself in any way. And no, the attack was not a credible warning to North Korea, it was an omission that Trump’s White House may not only react nearsightedly in a military manner to changing events, but also that they are only willing to do it in a highly limited and symbolic way. And North Korea is no Syria.

At Kim’s fingertips, in addition to nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, is a massive, blunt and deadly military force, much of which has been contoured to cause as much immediate pain and suffering to South Korea, the US and its regional allies following an attack than anything else. As such, there is no real limited “military option” when it comes to North Korea. Anything “kinetic” in nature is a crap shoot that could result in the immediate release of tens of thousands of artillery guns and rockets emplacements, most of which are buried in highly fortified revetments along the DMZ. These weapons, which can contain gas, will rain down on South Korea, including large parts of Seoul. The destruction and loss of life would be on a scale we have not seen since WWII, and no, there is no super weapon that can intercept this barrage.

There has also been some talk that Trump could order special operations raids into North Korea—ones that target regime interests and critical infrastructure. This would be just as reckless and bombing those North Korean targets. And it is not as if Pyongyang doesn’t have their own massive cadre of special operations forces that basically run on a suicide pact mentality. These forces are meant to infiltrate into South Korea during the opening hours of a conflict via submarines, low-flying and hard to target An-2 biplanes, and clandestine paths through and under the DMZ. Their one mission—to wreak all out havoc on South Korea’s population and military installations.

In the end the ante for “testing” North Korea militarily is exponentially greater than for Assad’s regime in Syria, regardless of their Russian backers. In fact, last week’s missile strike on Syria has only reinforced North Korea’s rationale for obtaining nuclear weapons and a credible delivery system that is capable of threatening the US. With that reinforced rationale and increased paranoia comes a lighter hair trigger that could set the region on ablaze.

So what could Trump do right now that would put greater pressure on North Korea without realizing a major escalation militarily? More military presence is always the first go to, hence the Carl Vinson’s new orders. This would also include more bombers and fighter aircraft being deployed to the Peninsula on training missions. The US Navy could also be ordered to interdict any and all naval traffic headed to North Korea and confiscate anything but the most basic human needs items. Electronic warfare and cyber attacks on North Korean communications and infrastructure could also be used to put pressure on the regime. Finally, and this would be a risky move but not as risky as attacking targets on North Korean soil or unleashing special operations forces into the country, Washington could order any North Korean test launch that ventures into international airspace shot down.

Doing so would be tricky, as the flight profiles that North Korea’s most advanced missiles fly for testing purposes can be unusually steep, but the idea would be to take them out when possible—and America’s Aegis ballistic missile defense equipped destroyers and cruisers would be the the right tool for that job, a handful of which are part of the Carl Vinson strike group. Still, even doing this would risk a violent reaction from Pyongyang, but the precedent of shooting down a missile in international airspace is a far cry from attacking targets within North Korea’s own borders. By limiting each missile’s flight time, it could slow North Korea’s ballistic missile program that has drastically accelerated over the last year.

These tactics could be paired with an increased push by China to get Pyongyang to sit down for talks. China is the only country who really holds sway over North Korea as the so called “Hermit Kingdom” relies on Beijing almost exclusively for energy, food stuffs and most other things. But if China won’t act, or if Kim simply won’t listen, and depending on which direction the political winds will blow in South Korean Presidential election, the US could find that enhanced deterrence is the only logical option, and that may very well include not just deploying US tactical nukes to South Korea, but having South Korea build out its own nuclear deterrent, a massive strategic shift that Trump has floated in the recent past.

Above all else, the idea that some grand “military option” exists today in dealing with the ongoing North Korean crisis—one that won’t feature a high probability of leaving scores of South Koreans dead and a region totally destabilized—is at best an absurdly high stakes game of chance, and at worst a nearsighted invitation to the worst war the world has seen in 70 years.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com