Vice President of the United States and Chair of the first National Space Council Kamala Harris vowed to halt U.S. destructive direct ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons testing earlier this week. This would make the United States the first country to do so, causing both concerns for America’s ability to target enemy satellites and optimism for the health of future low-earth-orbit access and operations.

Harris made this announcement during a visit to Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on Monday. There had been previous indications that the U.S. government might have been moving in this direction, including a call for an end debris-generating ASAT testing worldwide from Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks in December 2021.

An ASAT weapons test can include the actual destruction of an on-orbit spacecraft or object. the military-sanctioned destruction of an on-orbit spacecraft or object. Beyond the testing value, these events serve to signal adversaries that their space-based capabilities are not assured. While the target is typically an antiquated and out-of-service satellite — or even a piece of space junk — owned by the country doing the testing, the collateral damage that follows has the potential to span nations.

Harris touched on this during her announcement, vocalizing hope that the United States could “lead by example.” She urged foreign, spacefaring countries to follow suit after previous ASAT missile tests resulted in debris clouds that posed significant threats to the International Space Station and other potential space-based operations.

The Russian ASAT weapons test that took place in November 2021 is a particularly notable example of the issues at play when it comes to destructive anti-satellite weapon testing. During the test, a direct-ascent anti-satellite (DA-ASAT) missile was fired at a defunct Russian intelligence satellite designated as Kosmos-1408, causing what U.S. Space Command (SPACECOM) described to The War Zone at the time as a “debris-generating event.” Its impact on orbital operations would become even more clear in the days and weeks following the test.

In a subsequent press release, U.S. Army Gen. James Dickinson, head of SPACECOM, expressed the U.S. government’s core position on the test, stating:

“Russia has demonstrated a deliberate disregard for the security, safety, stability, and long-term sustainability of the space domain for all nations. The debris created by Russia’s DA-ASAT will continue to pose a threat to activities in outer space for years to come, putting satellites and space missions at risk, as well as forcing more collision avoidance maneuvers. Space activities underpin our way of life and this kind of behavior is simply irresponsible.”

Russia, however, isn’t the first country to crowd orbital paths with the aftermath of an ASAT weapons test.

In January 2007, a Chinese test resulted in what would go down in history as yet another major space-polluting event. A missile from Xichang Space Launch Center intentionally collided with a non-operational Chinese weather satellite, the Fengyun-1C, and created a cosmic mass of debris that Harris cited as a problem the U.S. government is still actively mitigating today.

“These tests, to be sure, are reckless, and they are irresponsible.” Said Harris. “These tests also put in danger so much of what we do in space. When China and Russia destroyed their respective satellites, it generated thousands of pieces of debris. Debris that will now orbit our Earth for years, if not decades.”

The Space Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron at Vandenberg is in charge of monitoring and tracking what remains of these debris clouds. Harris explained that the 18th has identified over 1,600 pieces of debris from the Russian ASAT weapons test, while over 2,800 pieces from both the obliterated Russian and Chinese satellites remain in orbit.

As it stands, Russia and China are both actively developing many technologies and weapon systems already intended to take out enemy satellites and spacecraft.

The U.S. military has conducted destructive ASAT weapon tests in the past, as well. This includes the destruction of the Solwind P78-1 solar observatory satellite using an ASM-135 missile in 1985 and the interception of the out-of-control spy satellite USA-193 with a modified SM-3 in 2008.

India became the most recent country to join this select group of nations that have conducted destructive ASAT tests in 2019. That test, which Vice President Harris conspicuously did not mention, was widely condemned at the time, particularly over the debris it produced.

The added threat of uncontrolled debris hurtling through orbital space creates a mess for all countries with a space presence to clean up, despite not making the mess in the first place. And cleaning up this debris still remains in the realm of theory, not practice. Next-generation connectivity solutions, GPS systems, communications networks, and countless other military and commercial capabilities are put at risk by the debris that follows an ASAT weapons test.

Despite the United States being one of the four countries that have participated in such experiments in the past, this new announcement comes with the hope of inspiring international adoption of best practices in space. The Artemis Accords, an international agreement authored by NASA and the State Department to outline principles for civil cooperation in space, was cited by Harris as a reference point for future rules that militaries could potentially adhere to.

While there is a finality to Harris’ announcement that could easily be perceived as the end of all DA-ASAT weapons testing for the United States, it is important to remember that she only announced a pledge to end ‘destructive’ tests. This leaves open the potential to carry out future DA-ASAT work, so long as it does not produce any debris in space. Defining how DA-ASAT testing differs from tests related to mid-course ballistic missile defense, which can also involve intercepting threats in space, will be important going forward, too.

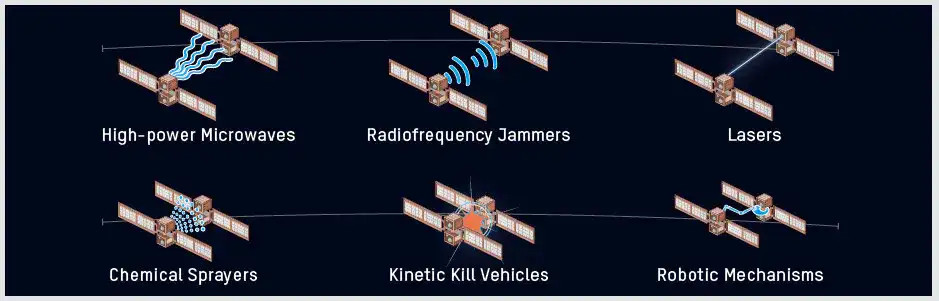

Still, the reality is that direct ascent methods of destroying orbital platforms already have increasing competition from on-orbit anti-satellite capabilities. Attacks on U.S. satellites are occurring every day from nondirect ascent methods, which can include using smaller ‘inspector satellites’ to maneuver close to and manipulate the operations of the targeting satellite. Once nearby they can jam the targeted satellite’s communications, blind its optics with lasers, use aerosols to temporarily or permanently block its view, or even obscure its optics and solar arrays. Other options include shooting a projectile at the satellite from another satellite or even having the ‘inspector satellite’ attach itself to it to disable the targeted satellite or even deorbit it. Satellites can also be temporarily degraded via jamming and laser dazzling from the ground, as well.

These capabilities are where ‘war in space’ is clearly heading, and are understood to be available now, to some degree, by major space players. But still, firing a missile to pulverize a satellite in orbit is a far less advanced proposition that has its benefits. During a time of war, eliminating the enemy’s space-based capabilities could be viewed as necessary in order to prevail or even survive at all, especially if they rely on them more than one’s own military. This is especially true for rogue states. So, even though direct ascent ASAT capabilities may become less essential to China, Russia, and the U.S., other countries without such space-faring abilities could rely on direct ascent weapon ASAT weaponry.

As it sits, for the U.S., the world’s most advanced space-faring power, direct ascent ASAT weaponry simply is not necessary and it endangers its own capabilities and access to low-earth orbit as a whole. In other words, it has a lot to lose. So, it isn’t surprising that the Biden Administration is willing to lead this initiative. Also, it speaks to the capabilities that the U.S. has as alternatives to direct ascent ASAT weaponry, all of which remain classified but have been heavily hinted at by top officials on numerous occasions.

The big question is, will anyone else follow?

Contact the author: Emma@thewarzone.com