China successfully placed its first crew members aboard its Tiangong space station, which is still under construction. Three taikonauts (astronauts) boarded the Tianhe core space station module in orbit, marking a new milestone in the Middle Kingdom’s rise as a global leader in space. While the launch of the Shenzhou-12 mission is significant on its own right as a demonstration of China’s space program, it also highlights growing concerns about Chinese ambitions in space.

The Shenzhou-12, or “Divine Boat” mission, is the seventh crewed Chinese spaceflight in history and China’s first space manned mission since 2016. Three astronauts, Commander Nie Haisheng, Liu Boming and Tang Hongbo, took off aboard a Long March 2F rocket launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Inner Mongolia on June 17. Seven hours after launch, the crew successfully docked with the Tianhe module in low Earth orbit (LEO) at an altitude of around 236 miles.

The Chinese astronauts will spend three months aboard the Tianhe bringing the module online and conducting tests of its systems ahead of other planned manned missions. Other modules will be added to the Tianhe and expanded into the full Tiangong space station in subsequent launches planned for later this year.

In a statement translated by the BBC, Commander Nie said the mission will be difficult and will help further the goal of establishing a Chinese space station. “We need to set up our new home in space and test a series of new technologies. So, the mission is tough and challenging. I believe with the three of us working closely together, doing thorough and accurate operations, we can overcome our challenges. We have the confidence to complete the mission.”

Shenzhou-12 marks the second flight to the Tianhe module after it was placed in orbit. An unmanned supply flight docked with the module in May 2021, and two more launches, the unmanned Tianzhou-3 and the manned Shenzhou-13, will follow later this year.

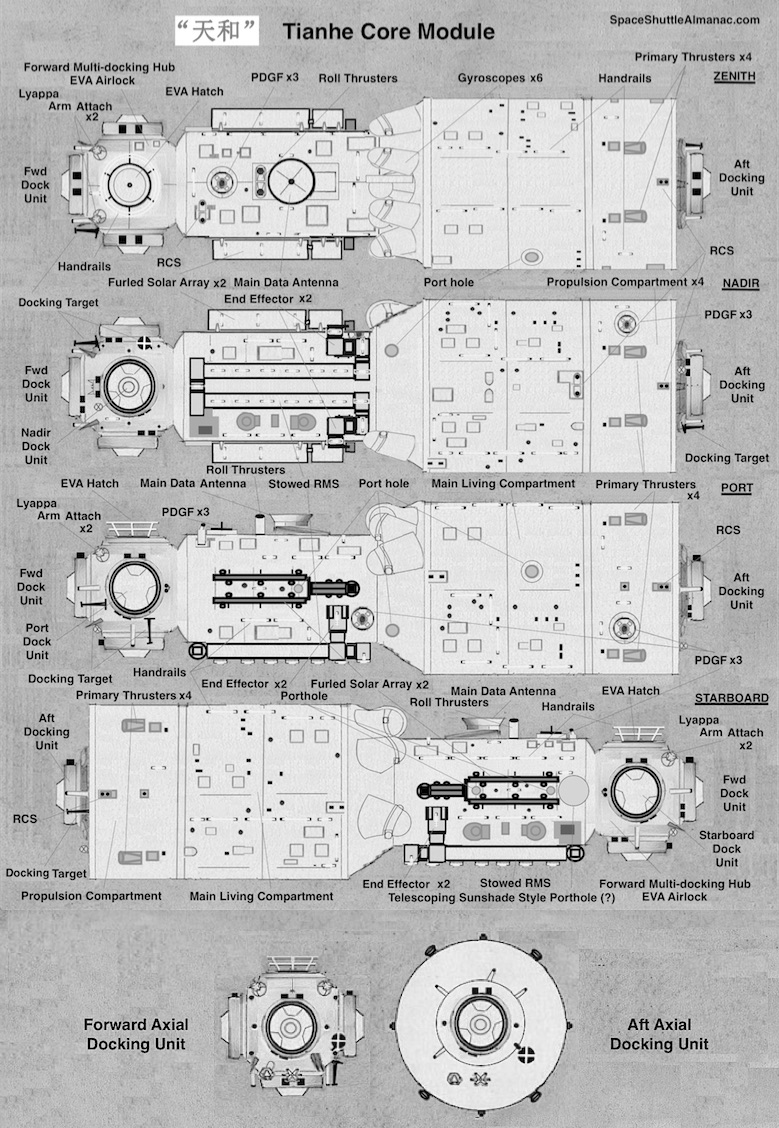

The 54-foot-long, 14-foot diameter cylindrical Tianhe core module was launched into orbit in April 2021 and includes living quarters for up to three crewmembers, life support systems, and power, propulsion, navigation, and guidance features for the entire Tiangong space station, which is expected to be completed by 2022. The entire module has just 1765 cubic feet of space for all of its equipment and systems in addition three crew members, making the three month stay for these taikonauts fairly spartan in terms of living conditions.

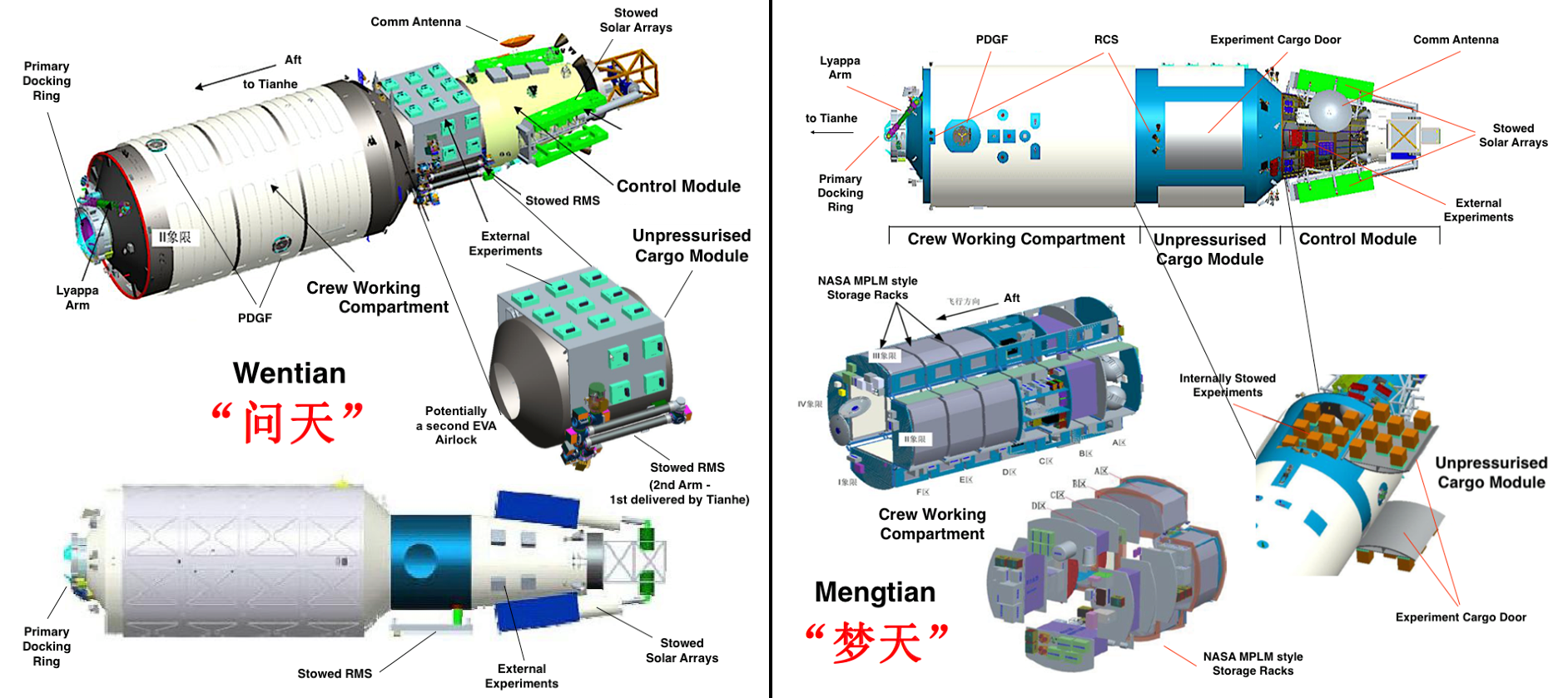

Aside from the Tianhe module, two laboratory cabin modules, the Mengtian and Wentian, will be added to the Tiangong space station in later missions planned for 2022. Both of those modules will expand the station’s navigation, propulsion and orientation capabilities in addition to enabling crew members to conduct scientific and technical experiments both inside and outside of the modules. In addition, China plans to launch a companion space telescope capable of independent orbit as well as being able to dock with Tiangong that is claimed to have a viewing angle hundreds of times wider than that of the Hubble Space Telescope.

Once completed, the Tiangong space station will have a mass roughly one-sixth of the ISS and will measure roughly 60 feet in length. The entire station has just 3,884 cubic feet of habitable space, and can house three astronauts. That makes Tiangong roughly the same size as the retired Russian Mir space station or America’s first space station, Skylab. Both of those space stations also had a maximum crew of three.

As progress on Tiangong is being made, the International Space Station (ISS) continues to encounter a range of problems and malfunctions. Just this week, astronauts were unable to conduct a planned installation of new solar panels due to technical issues and spacesuit errors. Last year, the ISS experienced a significant air leak and the breakdown of one of its critical life-support systems. The ISS has been in space for over twenty years now and its age is beginning to show, all while China continues to advance development of its own brand new space station.

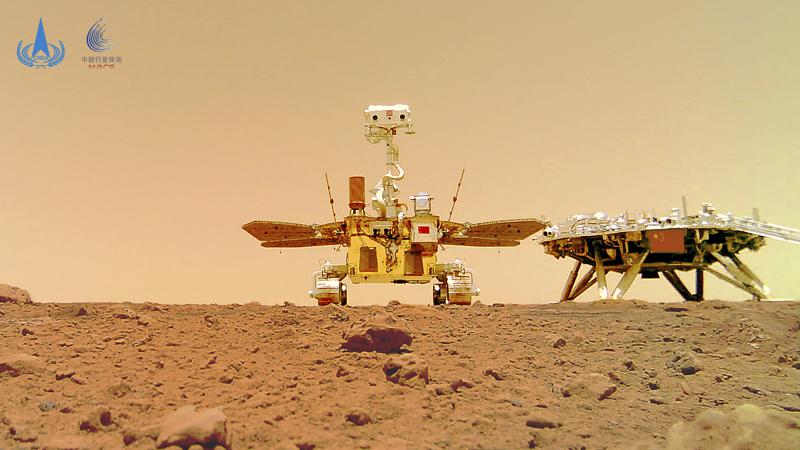

The Shenzhou-12 mission comes on the heels of several other recent major milestones for China’s space program. In late 2020, China successfully brought lunar soil and rocks back to Earth that were gathered by its Chang’e 5 lunar rover. In May 2021, China landed the Zhurong rover successfully on Mars to conduct a 90-day mission that includes collecting samples of the red planet’s surface and atmosphere. China has also conducted tests of more advanced spaceflight systems, including a reusable space plane similar to the U.S. Air Force’s shadowy X-37B.

China has also signed an intergovernmental memorandum of understanding with Russia that establishes plans for both nations to work together on a lunar research station. Construction is planned to begin in 2026 and continue through 2035, at which point the moon base will become operational in 2036. Russia and China unveiled a roadmap for the lunar base at the Global Space Exploration (GLEX) conference in St. Petersburg, Russia this week that contains plans for installations both in orbit around the moon and on the lunar surface, in addition to descent and ascent vehicles, surface energy and communications, infrastructure, and a variety of robotic systems, such as rovers. Russian space agency Roscosmos shared a concept video that outlines the moon base roadmap to social media this week.

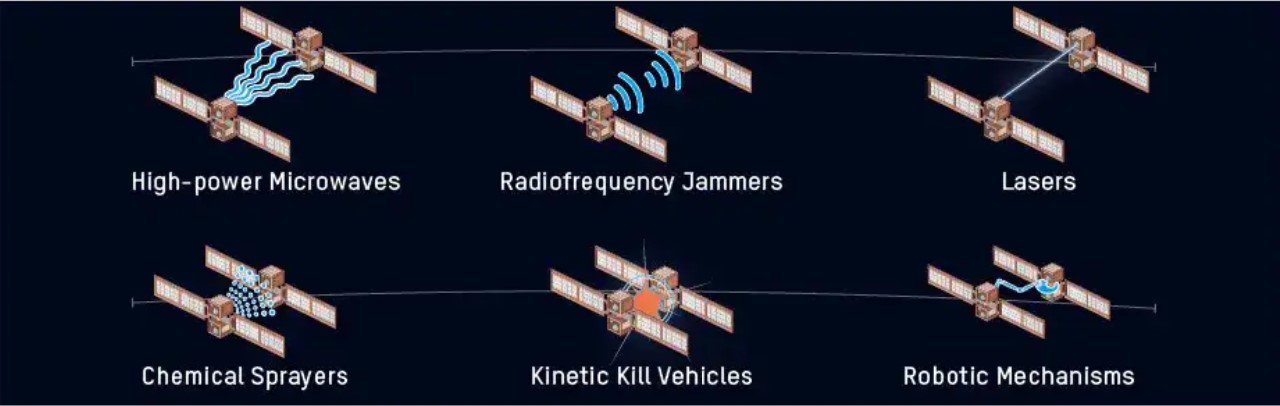

Already, the Chinese space station is raising concerns about its plans for its space program, given the program’s close ties with the Chinese military. U.S. Space Command (USSPACECOM) commander Gen. James Dickinson told the Senate and House Armed Services Committees earlier this year that China’s anti-satellite weapons, in particular, could soon pose a threat as China’s space program continues to advance and expand.

“They invest heavily in space, with more than 400 satellites on orbit today, and China could have as many as 1,000 on orbit by the end of the decade,” Dickinson told Congress. “China is building military space capabilities rapidly, including sensing and communication systems, and numerous anti-satellite weapons. All the while, China continues to maintain their public stance against the weaponization of space.”

In addition to other satellite and ground-based anti-satellite technologies, Dickinson specifically cited China’s deployment of a robotic arm aboard the experimental Shijian-17 satellite in his opening remarks to the Senate Armed Services Committee. Dickinson claimed the satellite could “be used in a future system for grappling other satellites,” although the China Academy of Space Technology has stated Shijian-17’s purpose is “high-orbit space debris observation technologies.”

There have long been concerns about the ability of certain space systems to have dual military-civilian capabilities. Much of the entire “killer satellite” discussion concerns what are publicly described as benign “inspector satellites” that inherently have the ability to maneuver close to other objects in orbit and engage with them, potentially in hostile ways. Any of these so-called inspector satellites could very well be described as being designed and intended to manipulate and observe space debris, while also being perfectly capable of being able to move other satellites out of orbit or otherwise render them inoperable.

As the Shenzhou-12 mission and other recent milestones show, China is a rising space power and, like any space program, this rise has military as well as civilian dimensions. Orbital space has quickly become a site of not just scientific exploration, but also geopolitical competition as nations become more and more dependent on space-based assets that support early-warning defenses, weapon guidance, intelligence gathering, navigation and communications, and more. As China, Russia, and the U.S. continue to expand their orbital presence, the development of space infrastructure, anti-satellite technologies and rapid launch capabilities will without a doubt become more of a priority.

Beyond the competition of space-based capabilities, the actual environment of space looks to become an increasingly contested domain. Competing space stations, using space as a transport route, could potentially become platforms to support various missions and operations including as a launch platform for cargo deliveries bound for Earth. The discussion has historically been about threats to space-based capabilities with respect to activities on the ground, but there is a clear push, especially in the US military, to at least explore the idea of developing different kinds of military presences in space itself.

While the U.S. has traditionally held the upper hand when it comes to space-based capabilities, the rise of China’s space program could tip the balance. Some experts have forecasted that China’s rapid progress could fuel a new space race, which could advance a wide range of technologies for both civilian and military applications as did the space race of the mid-20th century. It could also have potentially disastrous consequences during a conflict.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com