The U.S. Air Force is again looking to retire its fleet of iconic U-2S Dragon Lady spy planes by 2026, according to a new report. The service is also reportedly sticking to its previously announced plan to get rid of its remaining RQ-4 Global Hawk drones, the fate of which has often been intertwined with that of the U-2s, within four years. The planned divestment of the U-2s adds to other evidence in recent years that a top-secret, high-flying, stealth spy drone commonly referred to as the RQ-180, or variants or derivatives thereof, are close to becoming operational, if they aren’t to some degree already.

Aviation Week first reported earlier today that the Air Force’s U-2 fleet is again on the chopping block based on official information the outlet said it obtained. This follows the rollout of the Air Force’s latest budget proposal, which includes plans to cut 310 aircraft, but no Dragon Ladies, in the 2024 Fiscal Year. A single Global Hawk does stand to be divested in the upcoming fiscal cycle. As it stands now, the Air Force has around 27 U-2s, including a small number of two-seat TU-2S trainers, and some 10 RQ-4 Global Hawks, all Block 40 types, in service.

The War Zone has reached out to the Air Force to confirm and get more information about its plans for the U-2 and RQ-4 fleets.

In 2021, the Air Force had announced its intention to retire the U-2s by 2026. However, no mention was made of this last year when it rolled out its budget proposal for the 2023 Fiscal Year, which did include details about the separate plan to divest the rest of the RQ-4s by 2027.

This initially suggested the Air Force might have changed course and decided to keep the Dragon Ladies around while cutting the Global Hawks instead. This view was reinforced by the service moving ahead with the retirement of all pre-Block 40 RQ-4s, while leaving the U-2 fleet unchanged. The last Global Hawk left Beale Air Force Base in California, which remains a hub for the Dragon Lady, in August 2022.

The Air Force has gone back and forth in recent years about cutting one or the other of these fleets, but not both. So, the Air Force’s apparent actual plan now to cut the U-2s and the RQ-4s well before the end of the decade is a significant development.

The first versions of the U-2 and the RQ-4 entered U.S. service in 1956 and 2001, respectively. Today, the remaining examples represent the Air Force’s two highest-flying dedicated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets. Both types are also capable of flying across long distances without needing to refuel, with the Global Hawk having an endurance far in excess of the U-2.

The Dragon Lady is the service’s highest-flying aircraft of any type, at least that we know of. It can operate well above the Global Hawk. This particular fact was on full display as part of the U.S. military’s response to a high-altitude Chinese spy balloon that passed through U.S. and Canadian airspace for a number of days before being shot down off the coast of South Carolina. The War Zone was the first to report that U-2s helped monitor the balloon’s movements and gather intelligence about it. They were even able to fly above the balloon, an advantageous capability for various reasons, as evidenced by the selfie taken from the cockpit of one of the jets seen below.

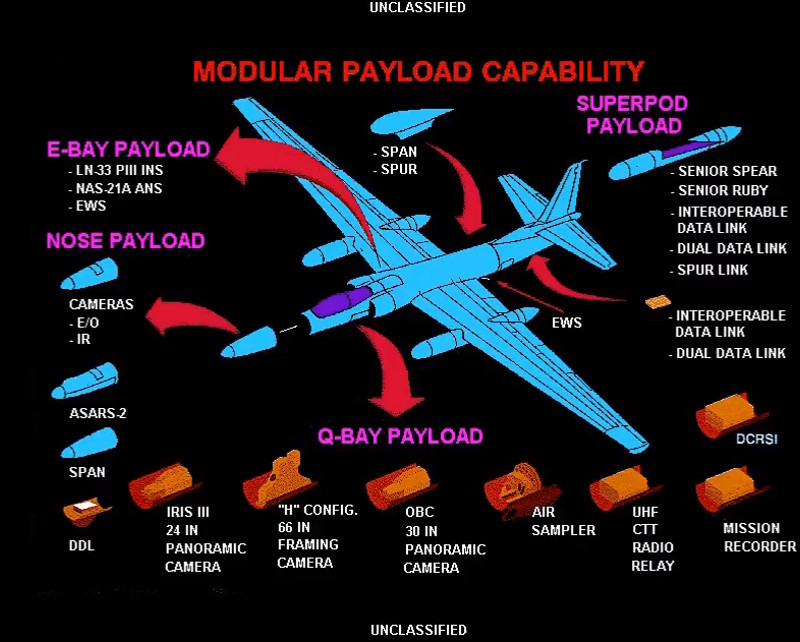

Since its introduction in the 1950s, the U-2 series has proven to be highly adaptable. The current U-2S variant can be configured to carry a wide array of sensors and other payloads as you can read more about here. Even more sensor capabilities for the Dragon Lady have reportedly been in development just in recent years.

The U-2s have also been increasingly used in various non-ISR-related roles. This includes acting as a highly capable airborne communications and data-sharing gateway node and as a testbed for new artificial intelligence-driven software and data-processing capabilities.

Despite efforts to expand its multi-intelligence capabilities, the Air Force’s RQ-4s have proven less flexible than the U-2s. The Block 40 Global Hawk’s only sensor is the AN/ZPY-2 Multi-Platform Radar Technology Insertion Program (MP-RTIP) radar, an active electronically-scanned array (AESA) type that is capable of collecting high-fidelity imagery in its synthetic aperture mode and has ground-moving target indicator (GMTI) functionality for tracking enemy forces down below.

Of course, that the Air Force is looking to retire the U-2 and RQ-4 is not entirely surprising. The service has been saying for years that it needs to replace various legacy aircraft, including ISR types, that it views as becoming too vulnerable and otherwise obsolete to make useful contributions in future high-end conflicts, such as a potential one in the Pacific against China. The loss of a U.S. Navy RQ-4N Broad Area Maritime Surveillance Demonstrator (BAMS-D), a variant of the early Block 10 Global Hawk, to Iranian air defenses in 2019 prompted a major debate about the utility of this entire family of drones in even moderate-risk environments.

“Legacy ISR platforms, once considered irreplaceable to operations, are often unable to survive or deliver needed capabilities on competition-relevant timelines,” Air Force Gen. Charles Q. Brown, who is still Air Force chief of staff, wrote in comments submitted ahead of a Congressional hearing back in May 2021. “These legacy platforms must be phased out, with resources used to invest in modern and relevant systems. Working together, we must take [a] calculated risk now in order to reduce the greater future risk.”

The exact specifics of the Air Force’s path forward from the U-2 and RQ-4 are unclear. What is clear is that the service has some kind of plan either already in place or in the works to make up for the loss of the distinct high-altitude ISR and other capabilities that the U-2 and the RQ-4, especially the former, provide.

“The Air Force has invested considerable time and effort in planning for divestments of ISR platforms, such as the MQ-9, U-2, and RQ-4,” members of the Senate Armed Services Committee wrote in a report last year accompanying a draft of the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for the 2023 Fiscal Year.

Air Force officials have all but outright said in the past that this includes a stealthy penetrating high-altitude long-endurance uncrewed aircraft commonly referred to as the RQ-180. In 2013, Aviation Week first reported on the existence of this specific drone.

In 2014, now-retired Air Force Lt. Gen. Bob Otto, then deputy chief of staff for Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance said that the service was working on an advanced drone to go “where the unmanned RQ-4 Global Hawk and manned U-2S platforms are vulnerable,” according to Air Force Magazine. That report indicated that Otto had referred to the RQ-180 by name, but did not quote him directly on that point.

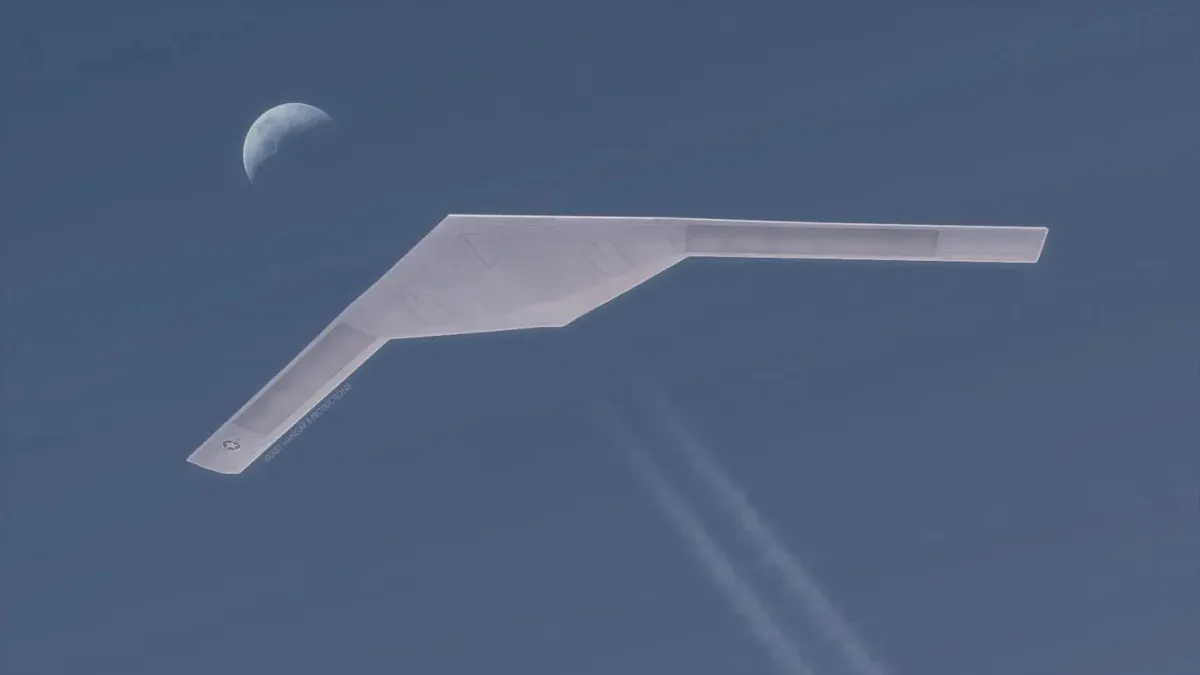

As The War Zone has reported on multiple occasions in recent years, there is growing evidence that this drone, or variants and derivatives thereof, is moving closer to entering service, if it isn’t already being used on at least a limited level in certain roles.

On top of that, all the signs point to the uncrewed aircraft being more than just an ISR platform, but also a communications and data-sharing node, similar to how the U-2 has been employed publicly in recent years. A platform like it could also be critical in the service’s Advanced Battle Management System initiative. You can read more about this in detail in this previous War Zone feature.

It is possible, if not probable that other advanced stealthy aircraft, or other capabilities, including space-based assets, could be part of the larger U-2/RQ-4 replacement equation, too. While more focused on tactical missions than the RQ-180, the RQ-170 Sentinel stealth drone is part of this larger intelligence-gathering ecosystem, and other types could be in development, or even in service, that are more oriented toward the tactical tier of penetrating ISR missions.

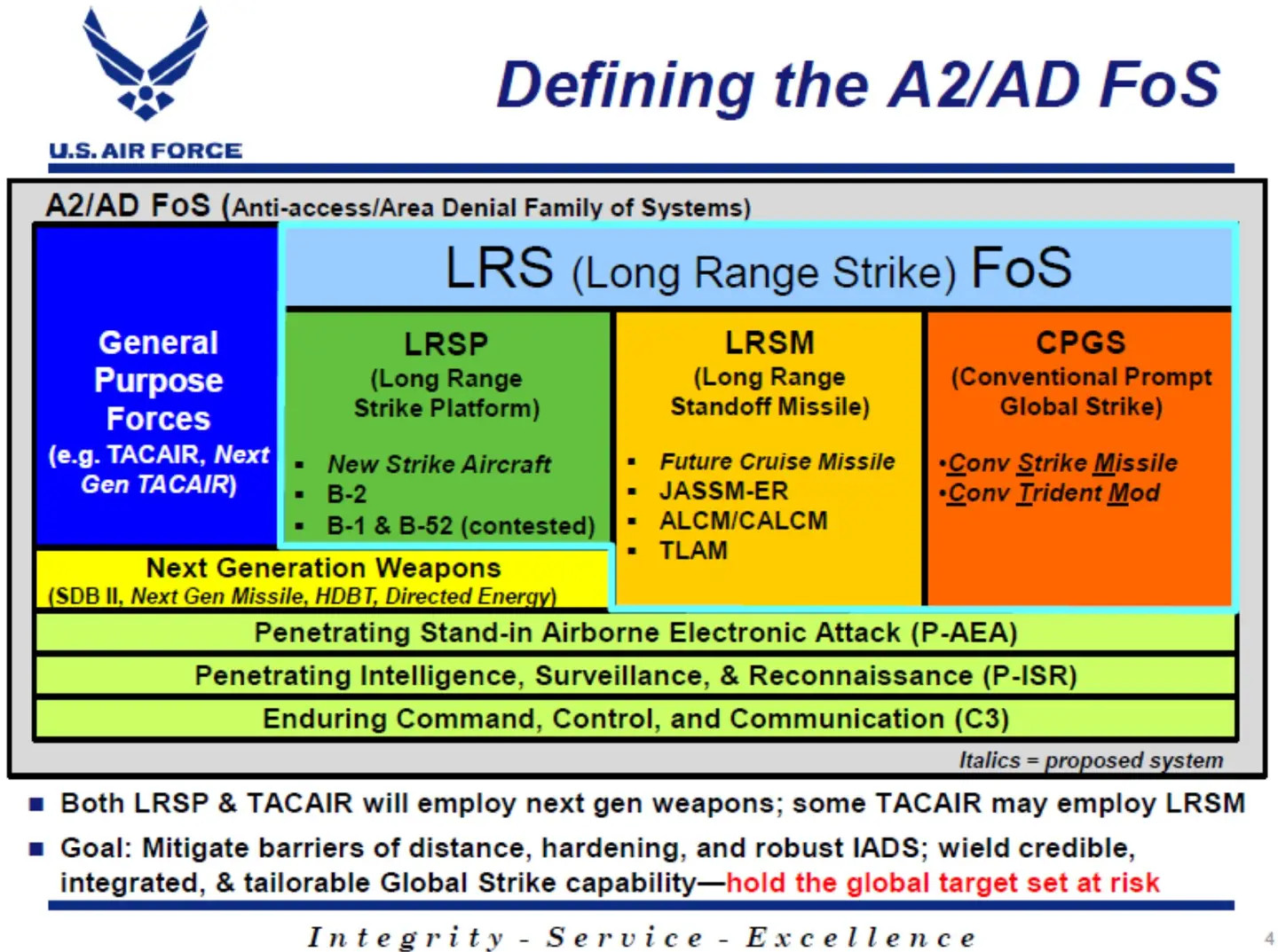

In his written statement ahead of the hearing in 2021, Air Force Chief of Staff Brown had specifically referenced plans to replace at least the RQ-4s with a future “penetrating ISR capability” as part of “a family of systems that includes non-traditional assets, sensors in all domains, commercial platforms, and a hybrid force of 5th- and 6th-generation capabilities.”

At a separate hearing that year, Lt. Gen. David Nahom, then the service’s deputy chief of staff for Plans and Programs, also mentioned “a family of systems” as part of the RQ-4 replacement plan, but said that “I’ll have to come back in [a] classified session to talk about that more.”

With this discussion of a family of systems, it’s interesting to point out that the Air Force has brought up penetrating ISR (P-ISR) capabilities in the past in relation to the secretive Long Range Strike Family of Systems (LRS FoS). The LRS FoS is known to include the B-21 Raider stealth bomber and Long-Range Stand-Off (LRSO) nuclear-armed cruise missile.

At the rollout ceremony for the bomber last year, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin specifically brought up ISR as being among the other mission sets that the Raider itself is expected to perform in addition to long-range strike.

“The Raider was built with an open-system architecture, which makes it highly adaptable,” he said during a speech at that event. “The B-21 is multi-functional. It can handle anything from gathering intel to battle management to integrating with our allies and partners. And it will work seamlessly across domains, and theaters, and across the joint force.”

The RQ-180 is rumored to be a Northrop Grumman design, like B-21, and would be paired with it operationally, at least in some regards. There have been reports in the past that the drone may have been utilized to help with risk reduction efforts related to the bomber.

All told, it remains to be seen how the Air Force will ultimately go about divesting its U-2s and RQ-4s, and what platforms and other capabilities may fill the resulting gaps. Congress, as always, may seek to slow or outright block these planned divestments, as it has done in the past with the Global Hawk fleet.

The U-2 still has a unique value that even a penetrating strategic drone does not. This is in its operational flexibility and ability to be used openly in uncontested or near semi-contested airspace. This has helped protect the fleet from cuts in the past. It can also be adapted to many types of payloads that do not have to adhere to a stealthy moldline.

At the same time, the Senate Armed Forces Committee report from last year mentioned earlier indicates that at least some legislators are aware of and confident in the Air Force’s plans behind these coming cuts.

What is becoming ever more apparent is that the Air Force feels that the careers of both types have finally run their course.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com