When was the last time you got your camera’s film developed at a 1-hour photo? You can’t remember, can you? Neither can we! Well, the folks at Beale Air Force Base in California have continued to process large amounts of film long after the digital imaging revolution swept massive brand names like Kodak and Fuji Film to the back of the public’s consciousness.

The U.S. Air Force’s 9th Reconnaissance Wing says that the U-2 Dragon Lady spy plane has flown Beale Air Force Base’s last Optical Bar Camera, or OBC, mission. In service for over half a century with the U-2, the OBC is one of the high-flying plane’s oldest sensor systems. Making its exit from Beale truly marks the end of an era in more ways than one.

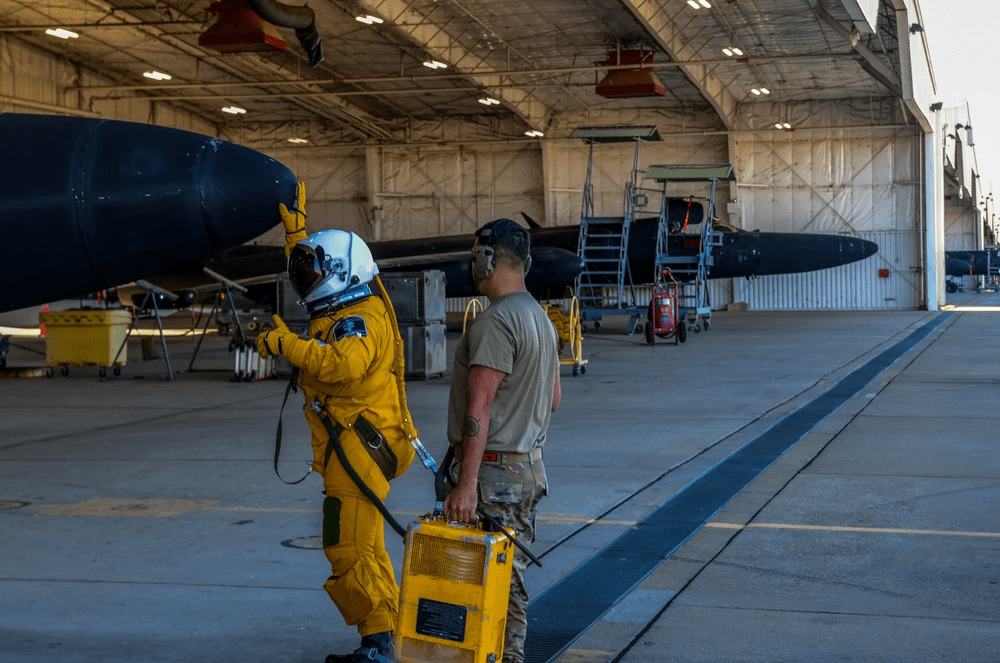

A Dragon Lady piloted by U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Ralph Shoukry flew the last sortie with the OBC from Beale — the home of the U-2 community — on June 24. Upon its return to the base, technicians ceremoniously lowered the sensor out of the jet one final time. Because the OBC is a wet film camera, its last flight from the base also effectively ended wet film processing at the 9th Reconnaissance Wing. With that, Beale’s U-2s have finally fully embraced the digital imaging age.

“This event closes a decades-long chapter for Beale Air Force Base and film processing, and it opens another chapter into the digital world,” Adam Marigliani, engineering support specialist for Collins Aerospace, which works with Beale’s intelligence gatherers to process OBC imagery, said in a USAF press release.

“The OBC mission operated out of Beale for close to 52 years, with the first U-2 OBC deploying from Beale in 1974,” wrote 2nd. Lt. Hailey M. Toledo in the official Air Force press release. “Pulled from the SR-71 [Blackbird], the OBC was modified and flight tested to support the U-2 platform, replacing the long-standing IRIS sensor. While the IRIS’s 24-inch focal length provided widespread coverage, the OBC’s 30-inch focal length allowed for significantly greater resolution.”

U-2 Dragon Lady, which took its first flight in 1955 and was eventually supposed to be replaced with the RQ-4 Global Hawk but only continues to impress, was designed from the very beginning with a high degree of modularity. This means that the OBC is just one of many sensor packages available for the aircraft, although this specific pairing has certainly carried out some historic intelligence gathering over the years.

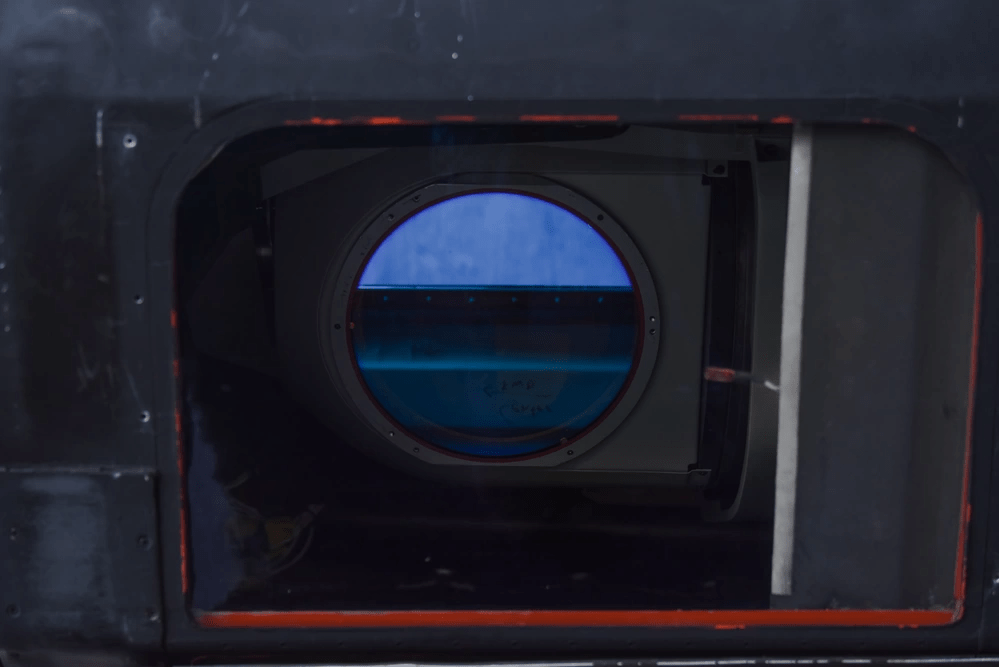

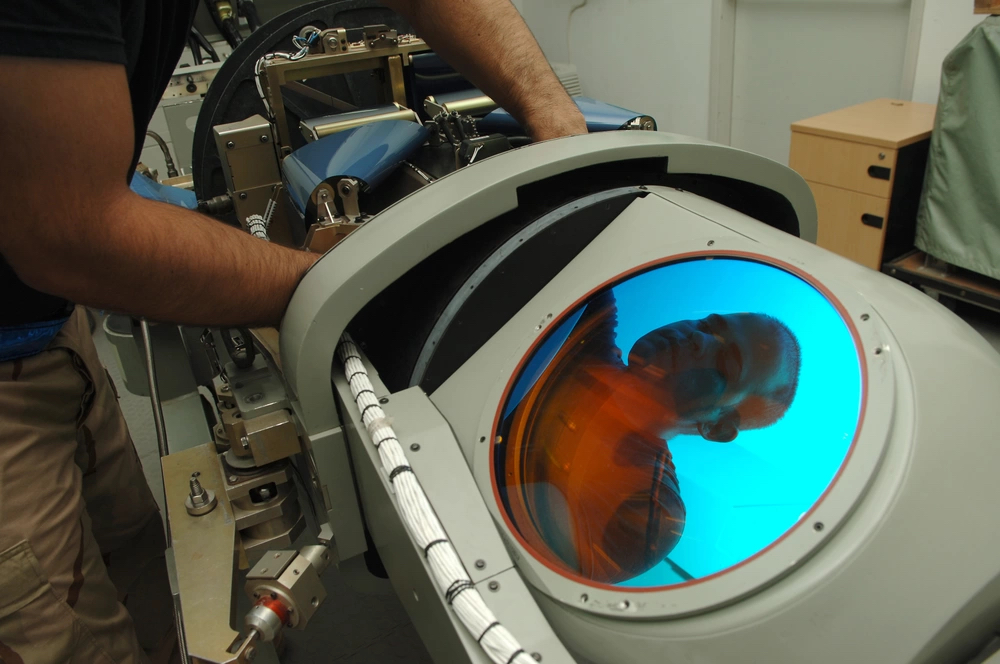

Designed as a long focal-length panoramic camera that oscillates back and forth to capture sweeping images, the OBC’s genesis extends far back into the 1950s. According to a blog post dedicated to explaining the camera’s origin, the first iteration of what would later be called the OBC was developed by a tech start-up known as Itek between the years of 1957 and 1965. The spinning reconnaissance cameras that Itek first engineered were intended specifically for the CIA to equip some of the world’s first spy satellites.

Once Itek went on to build versions of this imaging system for America’s spy planes, it finally became known as the OBC. Along with the U-2 Dragon Lady and the SR-71 Blackbird, the Apollo spacecraft was also a platform that went on to utilize Itek’s OBC payload. The blog post further explains that the cameras aboard these craft all featured a rotating structure called the roller cage, through which the film would pass, and fixed to the rotating camera that allowed the system to achieve its panoramic imaging capabilities.

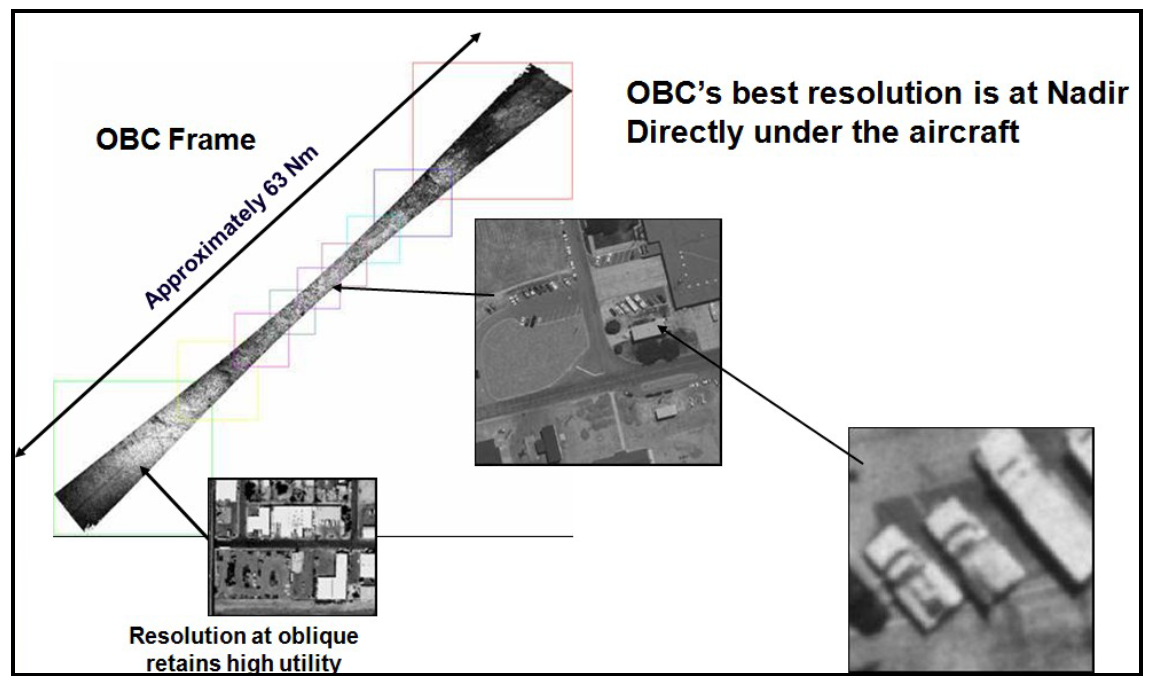

Listed among its technical specifications are a swath range of up to 134 kilometers and a massive “area collected” range of up to 362,000 square kilometers. A USAF release states:

“Each roll of OBC film is 5 inches wide and 10,500 feet long with each frame of imagery measuring more than 6 feet long… With an entire roll of film, the camera can take about 1,600 frames in one mission. Each frame covers roughly 110 square nautical miles in a panoramic horizon-to-horizon format. Basically, a roll of film can shoot an area the size of Colorado… When the OBC was on the SR-71 it took a frame about every 1.7 seconds, but for the U-2 it was slowed down to one frame every 6.8 seconds… This had to be done because the difference in the cruising speeds of the aircraft could cause the imagery to blur if the timing and speed of the camera was wrong.”

Although film held on to certain advantages — the OBC is still the U-2’s highest resolution imaging sensor — digital imaging has come of age and is superior in many regards, especially as it has matured over the last two and a half decades or so. Dealing with delicate film definitely presented its own set of drawbacks for aerial reconnaissance applications, as well.

“The basic problems with using film stem from the fact that the sensor surface is a thin, pliable, moving, relatively inexpensive object that has to be held within the camera with very high precision,” reads the blog post on the OBC. “There must have been several problems associated with getting the film aligned within +/- 11 microns of the lens’s focal plane. Among other things, the machines resemble Van de Graff generators, and so the film is subject to static electricity buildup and discharges, along with heating that tends to make it even more pliable and sticky.”

Despite the drawbacks presented by film and its cumbersome and time-consuming chemical developing process, the OBC served the Air Force aboard the U-2 for many decades to support an array of missions even as digital capabilities were becoming commonplace. The Air Force announcement noted a small selection of these use cases including Hurricane Katrina relief, the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster, as well as Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and Combined Joint Task Force Horn of Africa. Also mentioned in the release was the OBC’s time with the U-2 in Afghanistan, where the duo is said to have imaged the entire country every 90 days, providing the Defense Department with imagery critical to planning operations. Although, the OBC has been employed in a significant number of ways and locations throughout its extensive service, with its products being called upon repeatedly during the ups and downs of the Cold War.

The twilight of the OBC’s service saw a hybrid approach to processing and distributing the sensor’s high-resolution intelligence products. The film was downloaded and developed after the mission as normal, but then digitized and sent to ‘customers’ on hard disks. This hybrid approach made distributing and exploiting the imagery easier, but it still lacked digital’s near-real-time distribution capabilities.

Even though the OBC’s time at Beale has come to a close, the Air Force says that the U-2 will retain the capability to fly the OBC and that the operational know-how gained by U-2 pilots throughout the sensor’s service won’t be for naught either.

“All U-2 pilots will retain the knowledge and skills to employ the sensor through a variety of mission sets and operation locations to meet priority intelligence collection needs of the geographic combatant commanders as tasked,” said Lt. Col. James Gaiser, commander of the 99th Reconnaissance Squadron. “ The U-2 retains the capability to fly the OBC mission worldwide and, if called upon, to execute in a dynamic force employment capacity… With a growing need for more diverse collection requirements, the U-2 program will evolve to maintain combat relevance with a variety of C5ISR-T capabilities and combat air forces integration roles.”

So, the OBC will still be available for frontline expeditionary operations and can be returned to service if needed, with its film processed at forward locations where the U-2s are operating from. We also know that the OBC was flying test flights aboard a U-2 out of Lockheed Skunk Works’ plant in Palmdale, California just over a year ago. So, it’s not like it has totally faded into obscurity before this announcement was made.

Nothing is in the pipeline for the U-2 to replace the OBC’s wide-area super high-resolution imaging capabilities. Existing digital suites will provide radar (which can see through clouds and can isn’t limited to daytime conditions) and optical imaging, but their resolution is inferior to the OBC and they cannot collect as large of areas as the OBC could. This has left some of those who worked on the program somewhat dismayed at the decision to end OBC and film developing operations at Beale, outright calling it a tragedy:

Still, the U-2 retains many sensor configurations, which are continuing to improve, but the future of the U-2 force remains murky. The Global Hawk, which was supposed to replace it, is now being retired in large numbers, with only the latest block aircraft being kept on hand for frontline duties. Those aircraft have powerful optical suite options, as well. In fact, both can carry the incredibly capable, and digital, MS-177 sensor. Digital imaging combined with high-bandwidth communications also means it’s possible for some imagery to be beamed around the globe for dissemination in near-real-time — as opposed to downloading film canisters after the flight is over and developing it using chemicals. Of course, today satellites can do much of what the Optical Bar Camera can do, and even more, in some regards. Still, the OBC had unique capabilities and was truly the best sensor at its particular job. As such, it isn’t surprising that it will be kept in reserve if needed, at least for now and possibly as long as the U-2 keeps flying. And the death of the Dragon Lady has been predicted many times over the decades, yet it still flies critical intelligence-gathering missions around the globe today.

A high-flying very stealthy spy aircraft that can penetrate into contested airspace, not loiter outside of it with no defenses (aside from electronic warfare in the U-2’s case), will likely replace or at least further augment the U-2 and Global Hawk fleet. That secretive aircraft is flying in very small numbers today. And while Lockheed’s Skunk Works has come up with novel ideas to keep Dragon Ladies in the air for years to come, the nature of the threat has changed and operations in permissible airspace within range of the U-2’s sensors will no longer be an option in many wartime scenarios in the future.

Like the OBC itself, the U-2 could eventually be seen as something that is finally in need of phasing out, but what comes after may not be as good at all missions the U-2 presently covers, as is the case with Global Hawk. As such, don’t be surprised if the U-2s soldier on in reserve for special missions that are best suited for their unique manned capabilities even after its second try at a replacement becomes fully operational.

But for now, the Dragon Lady force is still going strong and Kelly Johnson’s legendary design is adapting to an increasingly digital reality nearly 70 years after it first took flight.

Contact the author: Emma@thewarzone.com