The U.S. Air Force is looking to get rid of all of its remaining Block 30 RQ-4 Global Hawk drones in the next year or two. The service says that it plans to replace those unmanned aircraft with a mixture of alternatives, including “penetrating” platforms and “5th- and 6th-generation capabilities.” Those terms generally refer to stealthy platforms able to get past hostile air defense works to conduct operations in denied areas. This comes amid an increasing number of reports that a new, secret stealth spy drone, commonly referred to as the RQ-180, which also looks set to act as a communications and data-sharing gateway, is close to entering operational service, if it hasn’t already.

Air Force General Charles Brown, the service’s Chief of Staff, offered these details in a hearing before the House Appropriations Committee on May 7, 2021. Additional information was contained in written remarks that the Department of the Air Force, to include Space Force, prepared for both that Committee and the Senate Appropriations Committee.

“Legacy ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] platforms, once considered irreplaceable to operations, are often unable to survive or deliver needed capabilities on competition-relevant timelines,” the written remarks say. “These legacy platforms must be phased out, with resources used to invest in modern and relevant systems. Working together, we must take calculated risk now in order to reduce the greater future risk.”

“For instance, the RQ-4 Block 30 Global Hawk was crucial to the ISR requirements of yesterday and today. However, this platform cannot compete in a contested environment,” that statement continues. “The Air Force will continue to pursue the FY21 NDAA [National Defense Authorization Act] RQ-4 Block 30 divestment waiver in order to repurpose the RQ-4 Block 30 funds for penetrating ISR capability. Overall, intelligence collection will transition to a family of systems that includes non-traditional assets, sensors in all domains, commercial platforms, and a hybrid force of 5th- and 6th-generation capabilities.”

This is not the first time the Air Force has attempted to retire some or all of its RQ-4 fleet, efforts that Congress has blocked in the past. The NDAA for the 2021 Fiscal Year said the service could obtain a waiver to begin divesting some of those drones if certain conditions were met, such as assurances there would not resulting ISR capacity or capability gaps, and appropriate justifications were provided to lawmakers.

The Air Force had asked in its Fiscal Year 2021 budget for approval to retire all 21 of its remaining Block 20 and Block 30 Global Hawks. It’s not clear from the information presented to the House Appropriations Committee whether the Air Force is looking to get a waiver to begin divesting Block 30 RQ-4s before the current fiscal year ends on Sept. 30, or if it’s hoping to start retiring those drones in Fiscal Year 2022, which begins on Oct. 1.

Separately, the plan now, as it was last year, also appears to be to retain the more modern Block 40 RQ-4s, at least for the immediate future.

How any of this might also reflect plans to scale back the Air Force’s U-2S Dragon Lady manned spy planes, another platform the service has proposed retiring on multiple occasions in recent years, is unclear. Discussions about the futures of the RQ-4 and US-2S within the Air Force have often been directly linked to each other. The Fiscal Year 2021 NDAA’s Global Hawk divestment waiver requirements also apply equally to any future decisions regarding the U-2S fleet.

None of this is necessarily surprising. The reality that the vast majority of the Air Force’s existing aerial ISR fleets would fare poorly in any kind of future contested environment against a near-peer adversary, such as Russia or China, if they were even committed to flying there in the first place due to the risks, is no secret. The service has admitted as much itself publicly on more than one occasion and first declared its intention to pursue a new “system of systems” approach to meet various future ISR requirements, as well other operational support needs, years ago now.

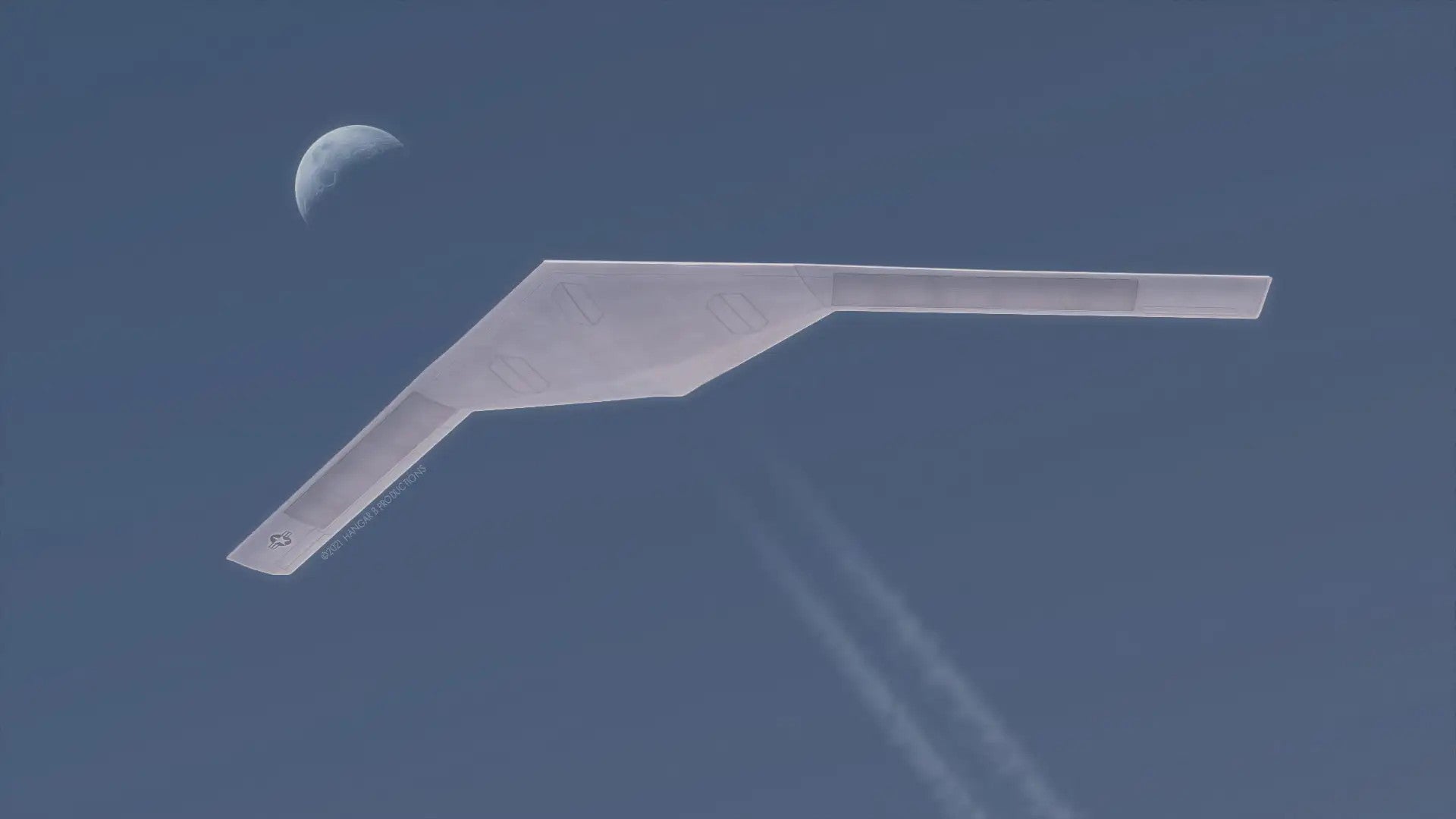

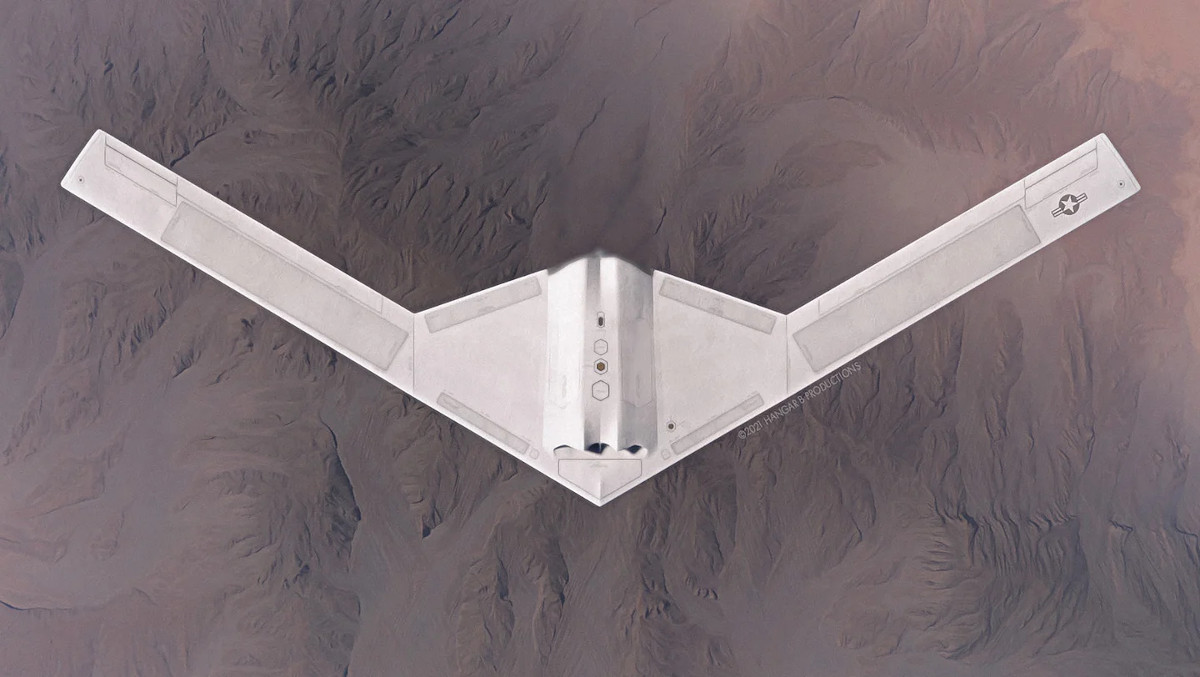

At the same time, the Air Force’s comments here about “penetrating ISR capability” and “5th- and 6th-generation capabilities” strongly point to work on the RQ-180, the report on which first appeared in Aviation Week the better part of a decade ago. In October 2019, another report from Aviation Week detailed evidence that this drone was close to entering operation service at that time, if it hadn’t already. In November 2020, a picture of what may have been one of these unmanned aircraft, or a related test article, flying over the Mojave Desert appeared online.

Just last month, The War Zone

published an in-depth feature covering a large body of evidence that all points to the RQ-180 being at the very center of a coming revolution in how the Air Force conducts penetrating aerial operations, as a whole, not just with regards to ISR. By every indication, this drone, or a derivative thereof, looks set to be a critical node in passing information to and from current and future stealthy aircraft, including the Air Force’s F-22 and F-35 stealth fighters, the existing B-2 Spirit and future B-21 Raider stealth bombers, and whatever platforms might be under development now as part of the service’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program. The Air Force’s RQ-170 stealth drones, which are understood to be more tactically oriented compared to the strategic-focused RQ-180, will also continue to be part of this overall ecosystem.

The RQ-180 would also link those platforms to other stealthy and non-stealth aircraft inside and outside of the Air Force, as well as nodes at sea and on the ground, including the service’s own expanding network of Common Mission Control Centers (CMCC). You can read more about the entire distributed networking framework that is already emerging publicly within the Air Force, as well as elsewhere across the U.S. military, and that the RQ-180 would be an important force-multiplier for, here.

Of course, as the Air Force has stated itself, its future ISR capabilities will involve a mix of platforms and capabilities, not just the RQ-180. Still, it’s hard to see how the service could retire a significant portion of its RQ-4 fleet in the next year or two in favor of a new “penetrating” platform, and convince Congress there is no risk of capacity or capability gaps, without something already at least close to being operational.

It will be very interesting to see what might emerge now about advanced ISR capabilities the Air Force is developing, or may already be employed in the classified realm, if legislators sign off on the service’s plan to be getting rid of the Block 30 Global Hawks.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com