Members of the U.S. Senate are pressing the Department of Defense to adopt more uniform policies to limit the ability of third parties, including the general public, to track U.S. military flights via their Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast transponders. Senators have expressed particular concern about the current ease with which aircraft carrying senior officials can be monitored. If these measures become systemically implemented, it could severely limit the ability for the public to track aerial movements of U.S. military aircraft.

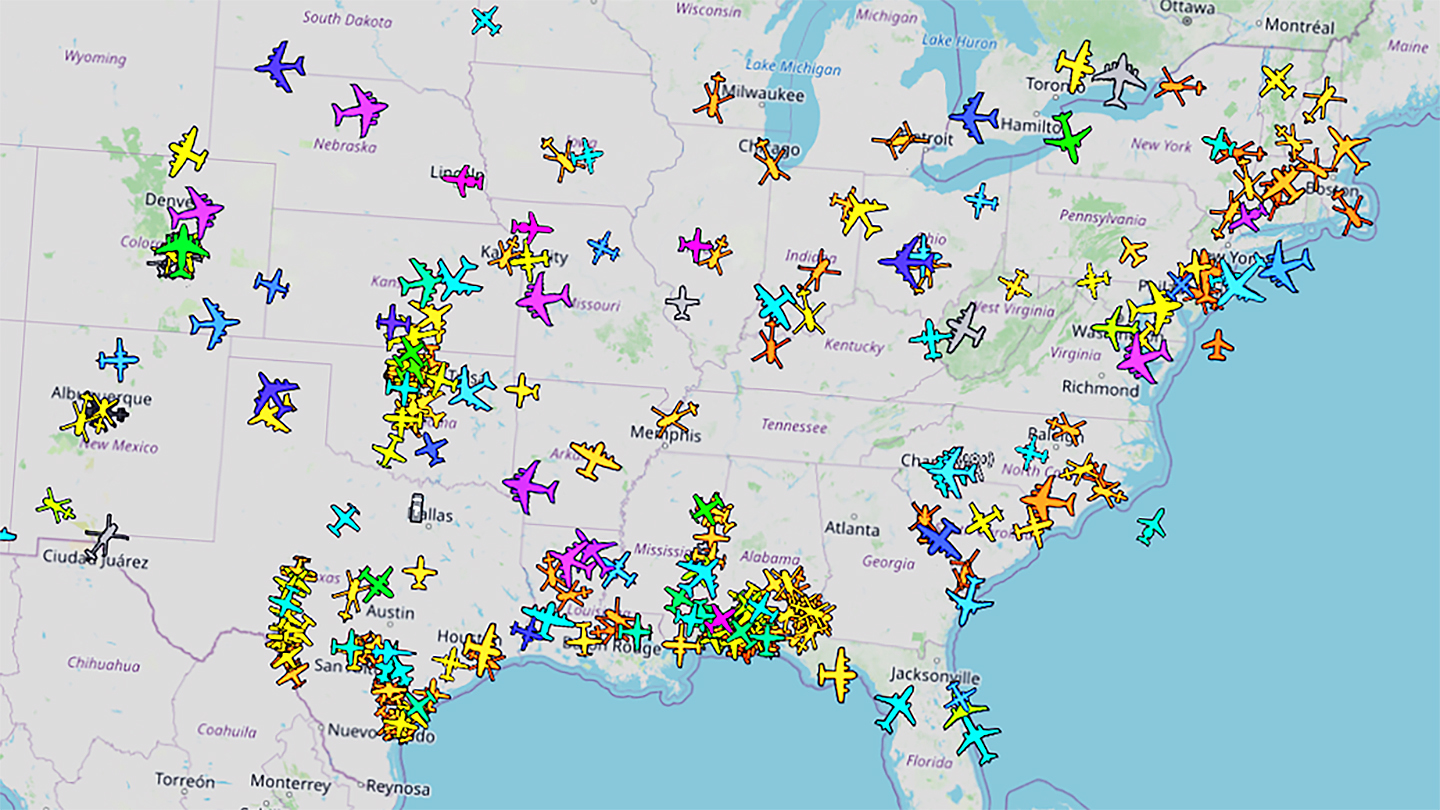

In recent years, tracking flights online via Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) and other data has become a particularly valuable tool for news outlets, including The War Zone, and other organizations. The power of flight tracking became particularly apparent as a result of investigations into the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) secret extraordinary rendition program in the early 2000s. Public advocacy and accountability-focused groups also regularly use this information to draw attention to other controversial or potentially wasteful use of military aircraft, including potentially illegal domestic surveillance and travel by top officials.

It has also prompted concerns about how foreign intelligence agencies and other malign actors might exploit this data.

The Congressional guidance in question was included in a report accompanying a draft of the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for Fiscal Year 2024 that Senators Jack Reed and Roger Wicker filed last week. Reed, a Democrat from Rhode Island, and Wicker, a Republican representing Mississippi, are the chairman and ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, respectively.

The full relevant section, titled “Mitigation of Aviation Transponder Vulnerabilities,” is as follows:

“The Department of Defense (DOD) has confirmed in briefings that it has developed a number of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), which it calls Joint/Interagency-Ground/Air Transponder Operational Risk Reduction, that are intended to mitigate the operational security threats posed by third parties tracking DOD aircraft through open source data broadcast by Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast [ADS-B] transponders. The Department has also confirmed that it has tested these TTPs and that they can be effective against tracking.

However, the Department acknowledges that the use of these TTPs is not consistently applied for sensitive DOD flights, in part because the decision whether to use the TTPs has been decentralized due to a lack of an overarching DOD policy.

The committee understands there are several software programs that track DOD aircraft, including aircraft DOD uses to transport senior government officials. The software is able to do this because these flights are not using the TTPs, making them readily tracked. Therefore, the committee expects the Secretary of Defense to address this situation by ensuring that a DOD-wide policy for preventing release of such sensitive information is promulgated as soon as possible.“

ADS-B transponders, which are in widespread use globally, broadcast precise location and other data, and do so in an unencrypted manner. Many countries require various types of aircraft to carry them for safety purposes and to otherwise help with air traffic control monitoring. This includes the United States, where Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations have required most aircraft, including military types, to employ this system since 2020.

In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration offers options to aircraft operators to withhold ADS-B data, but that only applies to what the U.S. government collects and releases. Since ADS-B is not encrypted, a number of publicly accessible websites now exist that display flight information in near-real-time based on information fed in from various non-FAA sources, including receivers operated by private individuals all around the globe.

Broadly speaking, from the perspective of Congress and the U.S. military, at least officially, fears lie in what bad actors might do with that information.

“The Department of Defense considers open source flight tracking and data aggregation on our aircraft a direct threat to our ability to conduct military air operations around the world,” the U.S. Air Force told National Defense magazine earlier this year.

As highlighted by the Senate report attached to the Fiscal Year 2024 NDAA draft, those concerns about those risks extend to non-combat activities, including the transport of senior officials from one location to another. It is also worth noting that the use of U.S. military aircraft by members of Congress and other U.S. government officials has drawn accusations of waste and abuse on many occasions in the past.

As a particularly notable and relevant example of high-profile U.S. military flight tracking, the U.S. Air Force C-40 Clipper aircraft that ultimately carried Nancy Pelosi, then a Democratic party Representative from California and Speaker of the House, to Taiwan last year was visible online despite concerns that the Chinese military might attempt to forcefully prevent the flight from reaching the island or otherwise harass it. That flight, which used the callsign SPAR19, was one of the most tracked ever in terms of total simultaneous users monitoring it on the popular site FlightRadar24.

Private citizens, most notably SpaceX and Tesla founder Elon Musk, have been increasingly voicing similar concerns, as well.

As the Senate report attached to the draft of the Fiscal Year 2024 NDAA notes, the U.S. government already has various tactics, techniques, and procedures it can use to mitigate those risks. The Senate Armed Services Committee did not provide specific details about these “Joint/Interagency-Ground/Air Transponder Operational Risk Reduction” tactics, techniques, and procedures, but there are a number of known capabilities and strategies that are relevant here.

It’s important to point out immediately that many U.S. military air operations are not readily trackable online at all. Tactical combat aircraft and bombers, in particular, routinely fly combat and non-combat sorties without broadcasting this data. U.S. military aircraft also have the option of flying with their transponders off entirely under so-called “due regard” procedures, including on sensitive flights outside of combat operations, wherein the pilot assumes full responsibility for keeping their aircraft safe and avoiding mid-air collisions.

When circumstances require U.S. military aircraft to publicly broadcast transponder data, there is also the option of using a more selective output setting known as Mode S. Transponders broadcasting in this way can be set to not pump out specific geolocation data or send out information of any kind automatically, unlike when using ADS-B. Aircraft using Mode S can still be tracked, but it requires at least four receivers pinging them to triangulate their lateral position and establish altitude. The Tweets below offer an example of how ADS-B versus Mode S flight tracking data might appear online.

With this in mind, open-source intelligence enthusiasts and analysts have been noting for some time now that the majority of instances of U.S. military aircraft disappearing from online tracking sites are very likely to be the result of them switching to Mode S rather than them turning transponders off entirely.

On top of that, ADS-B is only as good as the feeders available, and errors and dead zones are well-known issues in publicly-available flight tracking data. Deliberate spoofing is another issue that is becoming more pronounced and could potentially be used to deceive and misdirect perceptions during times of conflict or crisis.

The U.S. military is also known to use bogus hex codes, which identify a transponder as belonging to a specific aircraft, to help mask certain sensitive flights. For instance, the U.S. Air Force VC-25A Air Force One jet that carried President Donald Trump to Afghanistan in 2019 masqueraded electronically for a time as a KC-10 Extender tanker in this way.

It is, of course, worth noting that none of these TTPs to mitigate online flight tracking limit the ability of traditional plane spotters to visually observe aircraft coming and going from various locations. The U.S. Air Force has recently begun removing individually identifying markings on a host of different transport and tanker aircraft to try to mitigate this kind of manual flight tracking, as well.

As The War Zone has noted in the past, there are many questions about the utility of this strategy, especially given online flight tracking tools. It’s possible that these efforts could be bolstered by other measures to limit the ability for people to track U.S. military flights electronically.

Interestingly, The Intercept published a story yesterday that indirectly highlights the potential limitations of all these strategies. The secretive U.S. Joint Special Operations Command, which operates fleets of aircraft the identities of which are already heavily obfuscated visually and electronically, is reportedly interested in the possibility of acquiring an “Aircraft Flight Profile Management Database Tool” to help those planes ‘hide’ out in the open.

“When determining if the planned movement is suitable and appropriate, the ‘Aircraft Flight Profile Management Database Tool” reveals that the aircraft is primarily associated with a distinctly different geographic area. Additionally, ‘tail watchers’ have posted on social media pictures of the aircraft at various airfields,” a U.S. military procurement document uses as a notional scenario where this tool would be applicable, according to The Intercept. “Based on the information available, the commander decides to utilize a different airframe for the mission. With the aircraft in flight, the tool is monitored for any indication of increased scrutiny or mission compromise.”

How feasible it might be to create such a tool, at least in the near term, is unclear. Such a system sounds like it would need to leverage things like artificial intelligence and machine learning technology to help scrape and scan large amounts of data quickly.

Regardless, JSOC’s interest in this capability speaks directly to the broader issues at play and the difficulties in mitigating them in a world where flight tracking information of various kinds can be readily shared and disseminated in multiple ways online.

It is important to remember that what Senators are calling for in the report attached to the draft of the Fiscal Year 2024 NDAA is just a more uniform implementation of the existing mitigation techniques. What impacts doing that might actually have remain to be seen.

What is clear is that Congress is now actively pushing the Pentagon to take those steps, which could have significant ramifications for anyone who currently uses online tools to track U.S. military flights going forward.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com