Undersea sensors off the coast of northern Norway that are able to collect data about passing submarines, among other things, have been knocked out, the country’s state-operated Institute of Marine Research, or IMR, has revealed. The cause of the damage is unknown, but the cables linking the sensor nodes to control stations ashore are said to have been cut and then disappeared. This has raised suspicions about deliberate sabotage, possibly carried out by the Russian government, which definitely has the means to do so.

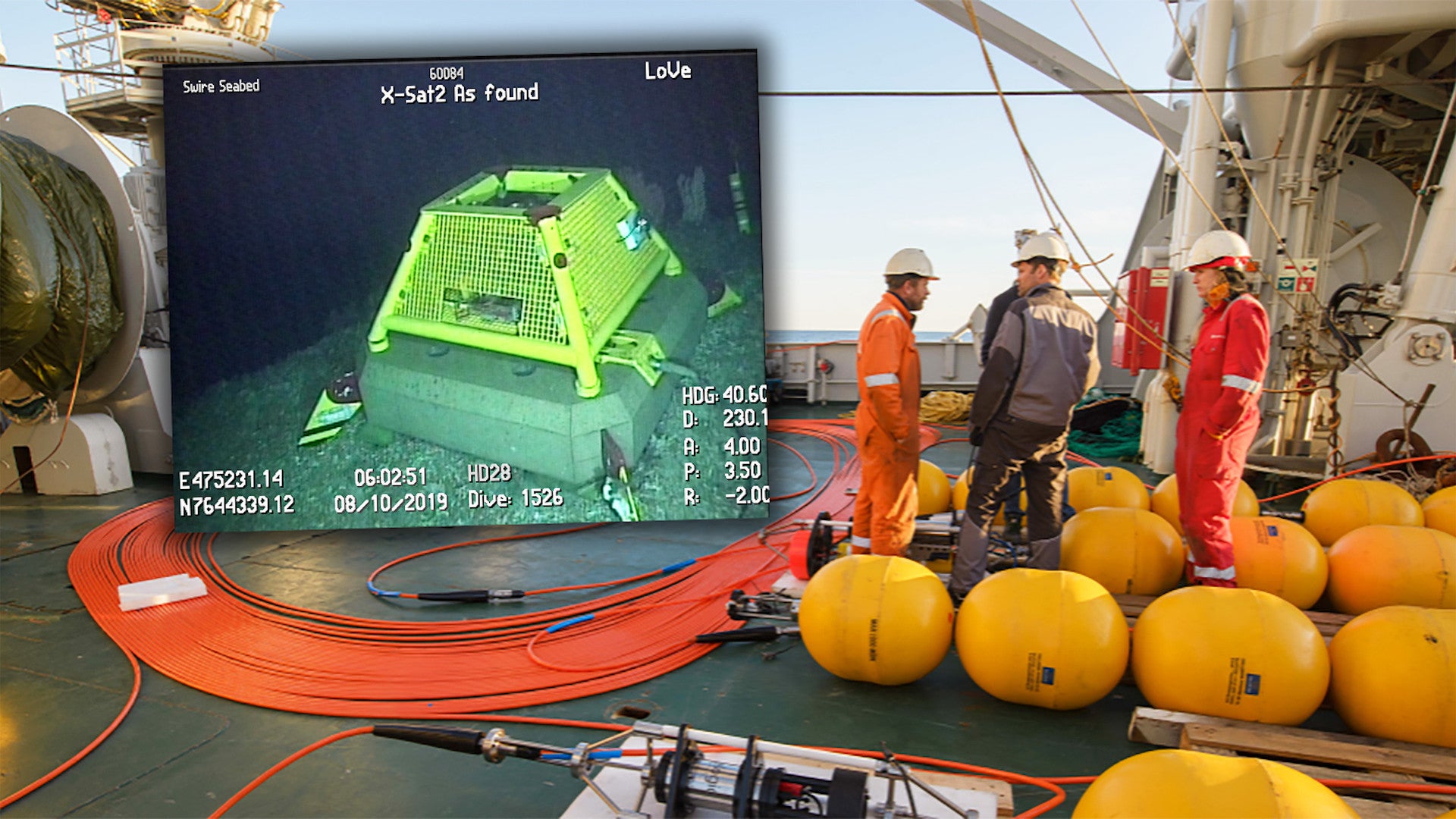

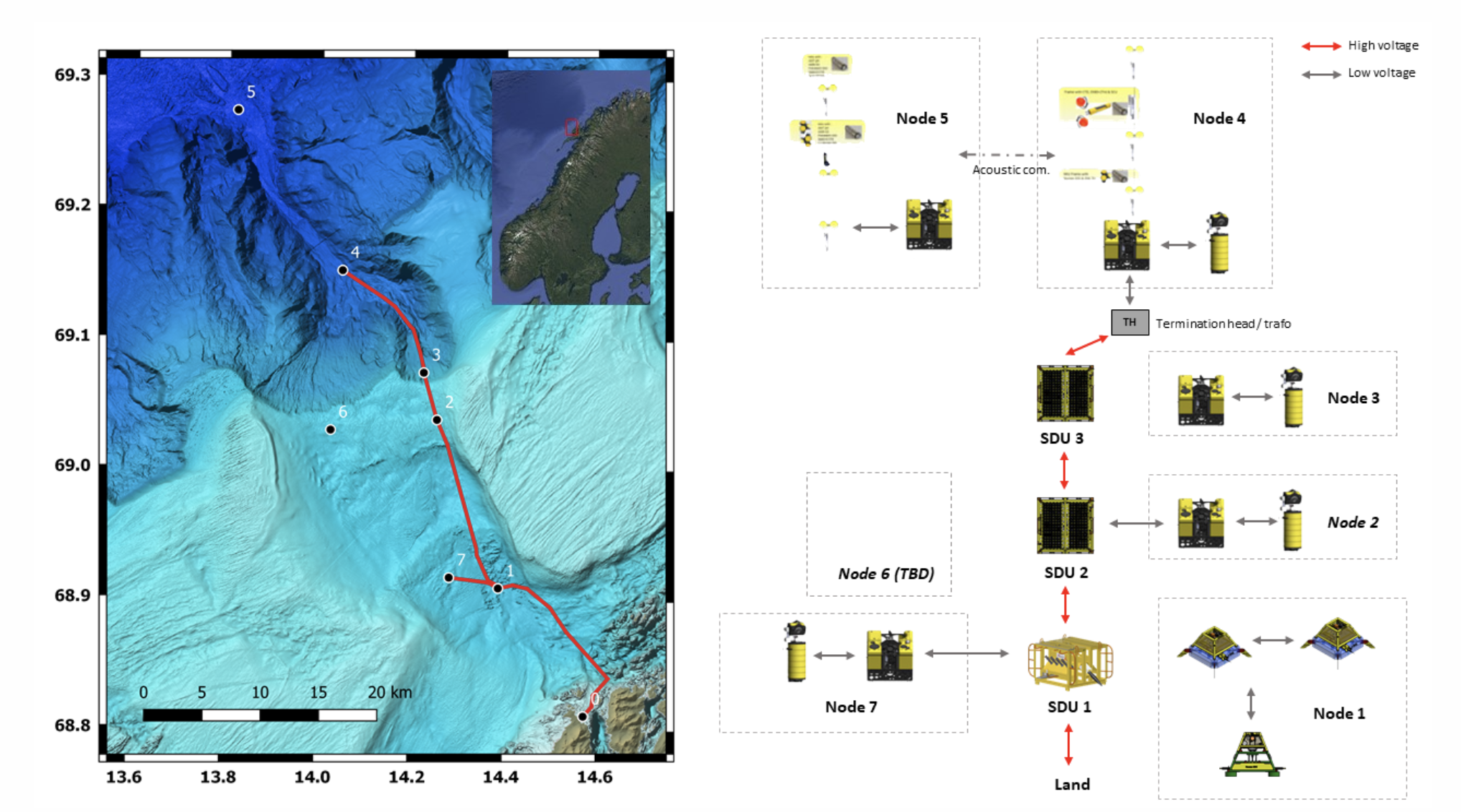

The IMR, one of the biggest marine research institutes in Europe, described “extensive damage” to the outer areas of the Lofoten-Vesterålen (LoVe) Ocean Observatory, putting the system offline. LoVe, which was only declared fully operational in August 2020, consists of a network of underwater cables and sensors located on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, an area of strategic interest for both Norway and Russia.

Norway’s military and the country’s national Police Security Service are reportedly investigating what happened to the research surveillance system. LoVe’s stated purpose is to use its sensors to monitor the effects of climate change, methane emissions, and fish stocks, providing scientists with a live feed of imagery, sound, and other data.

Of course, the system also monitors submarine activity in the area, so will immediately be of interest to the Russian Navy, in particular. Indeed, data gathered by its sensors is first sent to the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, also known by its Norwegian acronym FFI, before being handed over to the IMR for further study. “FFI is believed to routinely remove traces of any submarine activity in the area before turning over the observatory’s data to IMR so that it only contains fishing, currents, and climate information,” according to a report from Norway’s News in English website.

“We don’t care so much about the submarines in the area (located not far from onshore military installations at Andøya, Evenes and other bases in Northern Norway), but we know the military is,” IMR director Sissel Rogne told the Norwegian newspaper Dagens Næringsliv. “You could see what’s going on down there regarding all types of U-boats [submarines] and all other countries’ U-boats. That’s why I didn’t think this was just a case for the police but a case for [the police security agency].”

“Something or someone has torn out cables in outlying areas,” Geir Pedersen, the LoVe project leader, said in a press statement last Friday. Reports indicate that more than 2.5 miles of fiber optic and electrical cables were severed and then removed. In total, LoVe uses more than 40 miles of cables in the Norwegian Sea.

Based on reports in the Dagens Næringsliv, the LoVe observatory has been affected by interference since at least April, when the connection between the sensor network and the control station at Hovden on the northern island of Langøya was lost. An unmanned submarine subsequently traced the cause of the breakdown to one of the underwater surveillance platforms, Node 2, which had been dragged away from its normal location with its connecting cable severed and removed.

A follow-up mission in September attempted to trace the cable running from Node 2 with Node 3, only to find that this platform also had been moved, its components damaged, and its cable was missing.

Meanwhile, News in English

reports that the surveillance system has not been online since the initial disturbances to its operations in April.

Rogne told Dagens Næringsliv that the size and weight of the cable running between Nodes 2 and 3 was so great it would have required something with considerable power to have severed it.

IMR’s Øystein Brun told the same newspaper that the institute was now assessing whether the cables were cut deliberately, but suggested that seems the most likely explanation since the crew of a vessel should have noticed if they had accidentally become entangled with them and would likely have reported it.

It’s also unclear what has happened to the missing cable, around 9.5 tons in all, which has not been recovered.

Part of the investigation has sought to identify the vessels that were active in the area in question as of April this year. According to the IMR, that has been made more difficult by the fact that some of them likely were underway without transponders activated, meaning they would not have been broadcasting their positions to the Coast Guard or other agencies. Any vessel attempting to tamper with the cables would probably have had its transponder off, implying that a foreign power performed this act deliberately. In the meantime, at least some of the vessels in the area at the time have been identified, although no more details have been disclosed.

The reasons why a foreign nation may have attempted to sever the cables, and take them away, are several. First, as we have already seen, the surveillance system is an important means for Norway to track foreign submarine activity in the Norwegian Sea, potentially restricting certain operations in these waters. Second, this power may have wanted to explore the type of information that the LoVe system is capable of gathering, to give an idea of the sorts of capabilities available to Norway and, by extension, NATO. Third, as IMR director Rogne pointed out, the cables themselves may yield valuable technical information, for anyone wanting to install a similar system, for example.

The video below contains a recording from one of LoVe’s hydrophones of a larger ship passing by, highlighting the kind of acoustic data that the system can collect.

With the Russian Navy’s Northern Fleet on Norway’s doorstep, it would not be unexpected to see suspicion fall upon some kind of Russian espionage or sabotage activity, although the IMR is so far being circumspect on this matter. While we don’t know what happened, there could also be a more banal explanation, perhaps an unintended tangling of the cables with some kind of vessel or as the result of deep-sea dredging during oil exploration.

However, News in English

reports that there has been “lots of Russian shipping activity in the area of late, often cropping up around Norwegian offshore infrastructure.” In this case, the activity referred to is legal, but the implication is that this is an area in which Russia has a particular interest, and in which its vessels, naval and civilian, operate routinely.

While the area is very close to the Norwegian coast, it’s also adjacent to the Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom Gap, or GIUK Gap, a major strategic bottleneck through which Russian submarines would need to break through undetected if they wish to move out into the wider Atlantic without being traced.

Norwegian authorities have publicly disclosed Russian interference with and otherwise aggressive actions toward other sensor and communications networks in the region in the past. In 2018, the Norwegian Intelligence Service (NIS) disclosed three separate instances where Russian aircraft had flown mock attack profiles against a secretive radar station in the northern part of the country. The year before, the NIS blamed Russian jamming for disruptions in cell phone and GPS service in the region, though it said this was a byproduct of an exercise and not a deliberate attack.

Prior to these new developments involving the LoVe, various reports have suggested that Russia has been deploying boats at least close to undersea cables in the North Atlantic, part of a general uptick in its naval operations in those waters. Recent activity has included the presence of the survey ship Yantar off the Atlantic coast of Ireland in August. As well as carrying deep-sea submersibles and sonar systems, the Yantar has been repeatedly suspected of covert operations involving undersea cables.

“We are now seeing Russian underwater activity in the vicinity of undersea cables that I don’t believe we have ever seen,” U.S. Navy Rear Adm. Andrew Lennon, then serving as NATO’s top submarine officer, told The Washington Post in December 2017. “Russia is clearly taking an interest in NATO and NATO nations’ undersea infrastructure.”

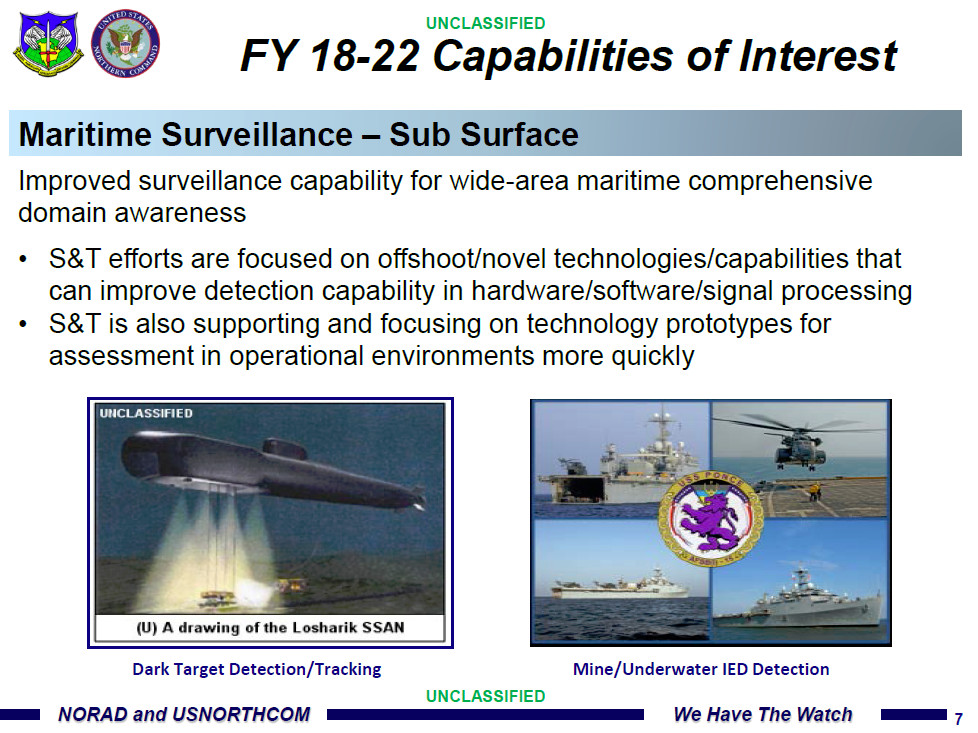

Certainly, Russia possesses special mission submarines that could well be equipped to both cut and tap cables, or even remove them for further study, as seems to have been the case with the LoVe network. In particular, U.S. Northern Command has highlighted the potential threat posed by the Russian Navy’s nuclear-powered midget submarine Losharik, compounded by the fact that it’s judged especially difficult to detect and monitor.

In an earlier piece on the Losharik, The War Zone described its covert role and unique capabilities as follows:

The Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research, Russia’s main naval intelligence entity, also known by the Russian acronym GUGI, operates Losharik and its primary missions are investigating, manipulating, and recovering objects on the seabed, such as hunting for items of intelligence value or tapping or cutting seabed cables. The small submarine is also designed to ride underneath a larger submarine mothership to get closer to the target area. GUGI has a number of motherships converted from ballistic missile and cruise missile submarines.

Losharik

has been laid up since suffering extensive damage in a fatal fire in 2019, but Russia has other similar special-mission boats available, as well as large mothership submarines capable of bringing them covertly to and from a mission area.

The capabilities thought to be provided by the Losharik, and others like it in Russian service, have long been a worry for NATO officials. Their concerns include hostile submarines operating close to their coasts and undetected while carrying out missions including tapping cables, deploying sensors, or otherwise collecting intelligence. Even one Russian submarine could potentially wield power far greater than its size, representing a powerful asymmetric naval threat by cutting cable completely as an information warfare tactic. While we have no evidence that this is what happened off the coast of Norway, it’s would be expected that this scenario would at least be a line of inquiry.

That the North Atlantic is an area of renewed interest for the Russian military is also no surprise, given the establishment of a new Northern Fleet Joint Strategic Command in 2014, responsible for the Arctic, North Atlantic, and Scandinavian regions. It includes the Northern Fleet, assets of which are concentrated on the Kola Peninsula, as well as military garrisons, and airbases, including a growing number of forward-located airfields in the High North. The Russian Navy has been exploring establishing underwater sensor networks and other infrastructure, including nuclear reactors on the seafloor to provide power, in the region, as well.

The United States has also stepped up its military presence in this wider region, with a particular tilt toward cooperation with Norway. In recent years, this has joint exercises in the air and on the ground and consideration has also been given to operating U.S. Navy submarines from a cavernous naval base built under a Norwegian mountain. U.S. Navy submarines have been a more visible presence in the region. This includes a rare publicized appearance by the first-in-class USS Seawolf surfaced in a fjord near Tromsø last year and an actual port visit there by the Virginia class attack submarine USS New Mexico in May of this year.

Seemingly, the LoVe case has proven very puzzling — and costly — for the IMR, although it’s not clear what kinds of evidence have been gathered by the Norwegian military or intelligence services. As it stands, however, for the time being, Norway has lost a very important source of surveillance for all manner of underwater activities. While the IMR will hope to bring at least a part of the system back online as soon as it can, the Norwegian Armed Forces will likely also be eager to have this source of underwater intelligence restored as soon as possible.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com