In the Vietnam-era U.S. military’s ceaseless quest to find new ways of sapping the morale of an often-elusive enemy, ‘ghosts’ were drafted in, too, as part of Operation Wandering Soul. It broadcast an eerie soundtrack of human voices as well as moans, screams, and shrieks, all calculated to mess with the minds of the enemy. The ultimate success (or otherwise) of this bizarre psychological warfare operation is hard to determine, but the surviving soundtrack of the so-called “Ghost Tape Number 10” makes for fascinating listening … especially around Halloween.

In Bao Ninh’s famous Vietnam War novel

The Sorrow of War, the protagonist, Kien, is given the job of helping to recover the remains of fallen soldiers once the Americans have left the country. The story, while fictionalized, is based on the real-life experiences of Vietnam’s Missing in Action teams, who gathered the dead while haunted by the conflict and what it had left behind.

Ninh’s recollections of the battlefields — “Bloated human corpses, floating alongside the bodies of incinerated jungle animals, mixed with the branches and trunks cut down by artillery, all drifting in a stinking marsh” — remain in the reader’s mind, but so do the descriptions of the many ghosts that populate the jungles and the imaginations of the soldiers and civilians who survived.

In the traditional Vietnamese understanding of death, ghosts play an important role, tied in with concepts of “good deaths” and “bad deaths.” Many of the almost one million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong war dead were understood as being in the category of “chet duong,” meaning that they had died violently, away from their family homes, and were unable to transition properly from the living world to the spirit world. Instead, tradition has it, their spirits were left to wander the battlefields, suspended between this life and the next.

In traditional Vietnamese culture, these ghosts are known as ‘linh hon,’ or wandering souls.’

Ghosts, in general, had been identified by the U.S. military as a potentially effective element of psychological warfare operations in Vietnam. A U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) fact sheet published in December 1969, a portion of which you can find reproduced here, even outlined different types of ghosts that might be mobilized in support of psyops campaigns. The document describes the “ma heo” (pig ghost), “ma cho” (dog ghost), and “ma meo” (cat ghost) that were part of rural folklore in Vietnam. Other, more malevolent spirits included “the ‘tightening-knot ghost,’ which goads people into suicide by muttering ‘co co’ (neck, neck) into their ears. Ma A Phien is the opium ghost, related to addiction and eventual ‘death in the pleasures.’”

In its essence, Operation Wandering Soul had much in common with previous psychological warfare efforts, broadcasting specially prepared audio tracks to undermine the adversary. The difference was how it relied on this particular Vietnamese idea of the battlefield ghost to spook the enemy.

The surviving Ghost Tape Number 10 was prepared by the U.S. Army’s 6th Psychological Operations Battalion, or 6th PSYOP Battalion, which had been activated in Vietnam in November 1965. Worthy of a horror movie soundtrack, it deployed disembodied voices and other unearthly sounds that would carry through the jungle like the wandering souls themselves.

These were not just spooky sounds engineered to creep out the listener but were intended to have a much more visceral reaction among troops very likely to be familiar with the idea of “chet duong.” After all, for the credulous, what they were hearing was nothing less than the sounds of the fallen soldiers they had once fought alongside. South Vietnamese participants were brought into the recording process to make the audio tracks sound more authentic.

Ghost Tape Number 10 was employed by the units of the U.S. Army and Navy, broadcast from loudspeakers on helicopters, Patrol Craft Fast (PCF) “Swift” boats, or by specialist infantry who would infiltrate enemy areas, normally at night.

“My friends,” pleads a disembodied Vietnamese voice on the tape. “I have come back to let you know that I am dead… I am dead!”

“It’s hell. … I’m in hell!” the track continues. “Don’t end up like me. Go home, friends, before it’s too late!”

As well as the voices of fallen soldiers, the same tape included banging gongs, crying women, and a child calling for her father.

To be sure, this particular psywar campaign was not always effective. There are reports of soldiers immediately opening fire in the direction of the speaker-equipped helicopters broadcasting it, for example. Another time, it’s reported that the crew of a Swift boat gave up playing the ghost tape in favor of Tina Turner after their boat began to be targeted with rockets.

Since leaflet-dropping, surrender pamphlets, and other propaganda broadcasts were already widely employed already, many troops would have been familiar with the broader concept of U.S. psyops campaigns.

Others reckon that Ghost Tape Number 10 was at least sometimes very effective. “Even if the Viet Cong didn’t believe there were in fact ghosts in the jungle with them, that this was just a supernatural horror show being put on by the Americans, just the sounds and the message were more than a little eerie,” explains Nathan Mallett, of MilitaryHistoryNow.com, on The Stuff of Life

In one truly remarkable extension of the ghost tape idea, it’s said that the 6th PSYOP Battalion added a tiger’s roar, capitalizing on rumors that there was a dangerous big cat attacking North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong troops. A former member of the battalion recalled the incident to psyops researcher Sergeant Major (ret.) Herbert A. Friedman:

The 6th PSYOP got an Air Force pilot to fly to Bangkok, to get an actual recording of a tiger from their zoo. We had a Chieu Hoi [a Viet Cong defector] come down the mountain and tell of a tiger that was attacking the Viet Cong for the past few weeks. So, we mixed the tiger roar onto a tape of 69-T, “the Wandering Soul,” and a two-man team got up on the mountain, played the tape and 150 Viet Cong came off that mountain.

As well as that account, there are reports of the tape being played in different parts of South Vietnam in late 1969 and early 1970 “with mixed results.” One mission, carried out in the jungle near the U.S. Army’s Fire Support Base Chamberlain in Hau Niga Province, on the night of Feb. 10, 1970, was described in a contemporaneous account in The Tropic Lightning News, which is reproduced here:

If you were a Wolfhound of the First Battalion, 27th Infantry, 25th Infantry Division, and were at Fire Support Base Chamberlain on the night of February 10 you might have sworn the place was being haunted by poltergeists, ghosts that is. The moans, groans, and weird sounds began at eight that night, a likely time for the cloudlike forms to reveal themselves. Of course, ghosts are nonexistent, or are they? In this case, the ghosts and weird sounds were furnished by the Sixth PSYOP Team and the S-5 Section of the 1/27th Wolfhounds who were conducting a night mission at Chamberlain. With the help of loudspeakers and a tape of ‘The Wandering Soul,’ a mythical tale of a Viet Cong gone to Buddha, the mission was a success.

Furthermore, Raymond Deitch, who had commanded the 6th PSYOP Battalion, later recalled that “The tape was so effective that we were instructed not to play it within earshot of the South Vietnamese forces because they were as susceptible as the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese Army.”

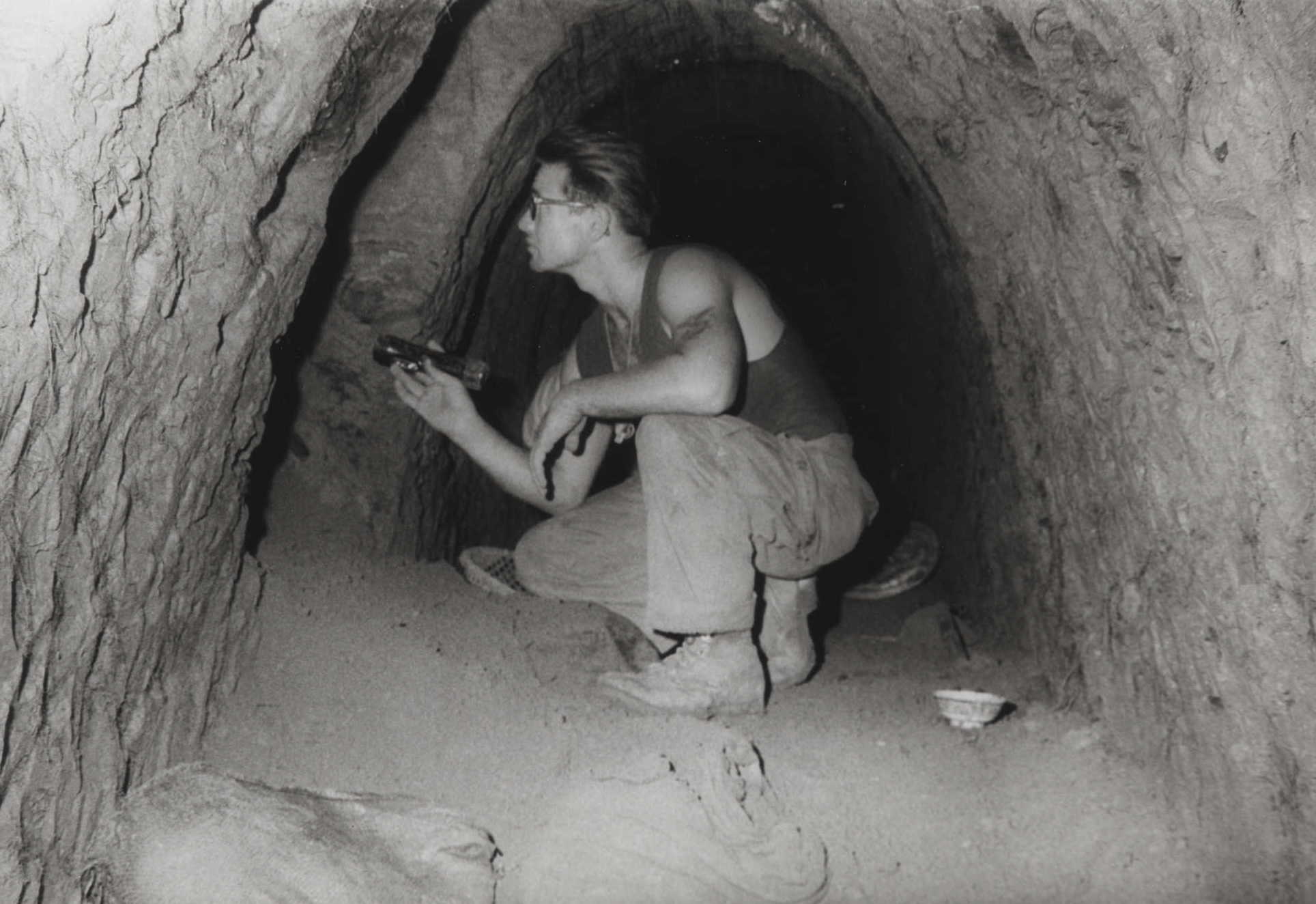

There’s even some evidence that the enemy leadership was indeed worried about the possible results of the ghost tape, and psyops broadcasts more generally. One account of the 4th Psychological Operations Group in Vietnam has it that a Viet Cong commander complained that “audio messages were hard to ignore, for the sound even penetrated through the earth to VC hidden in underground tunnels.” The same commander apparently pointed to Ghost Tape Number 10 as being particularly effective.

On the other hand, even on the occasions that the ghost tape backfired and instead drew enemy fire, that could also be useful to uncover the location of the adversary. One unnamed U.S. Navy helicopter pilot told Herbert A. Friedman that their crew played the ghost tape “many times” in 1968 and 1969. “On about half the missions a PSYOP officer would fly with us and attempt to direct the mission. We dropped leaflets, magazines, and played the tape. Without exception, we drew fire each mission. This was one of the primary objectives of the mission.”

Ultimately, it seems the success of Operation Wandering Soul was mixed, at best, at least when it came to diminishing the fighting morale of the enemy and motivating defections. However, similar concepts have resurfaced in successive U.S. campaigns since then, including the use of heavy metal music to make Manuel Noriega surrender and the broadcasts of crying, retreating troops, and other confusing sounds used against ISIS in the Middle East in recent years.

But the sinister sounds of Ghost Tape Number 10 provide a remarkable glimpse into the psyche, real or imagined, of the different antagonists involved in the war in Southeast Asia.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com