Matt Damon announces to the crowd, “We have an early Christmas present for you.” Kenneth Branagh takes over, holding court with an adoring audience. Playing General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, and nuclear physicist Niels Bohr respectively, the two A-listers herald the arrival of the Danish scientist at Los Alamos. This is the secret facility established in New Mexico in 1943 to build the first atom bomb and recreated 80 years later by Christopher Nolan to film his epic hit movie, Oppenheimer.

“The British pilots put me in the bomb bay,” Branagh as Bohr laughingly recounts in his best Danish accent, they “showed me the oxygen — of course, I messed it up. When they opened me up in Scotland I was unconscious. I pretended I’d been napping.”

The scene barely hints at the knife-edge circumstances of the Dane’s dramatic escape from Nazi-occupied Europe, nor the remarkable story behind his flight to safety. While researching my new book, Mosquito, about the U.K. Royal Air Force raid on the Gestapo headquarters in Copenhagen, I discovered the fascinating truth about both.

At the time he joined the Manhattan Project, Niels Bohr was perhaps the most famous scientist in the world after Albert Einstein. His Danish homeland had been under German occupation since April 1940.

On the day of the invasion, the professor was in the lab in Copenhagen that he had set up, attempting to dissolve a pair of Nobel medals in a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acid. Bohr was trying to stop the Nazis from getting their hands on two 23-karat-gold Nobels he’d been given for safekeeping by two Jewish German physicists fleeing the antisemitism of Hitler’s Germany. He’d auctioned off his own Nobel medal in 1940 to raise money for victims of Finland’s ‘Winter War’ with the Soviet Union. That he’d allowed the institute in Copenhagen that carried his name to provide sanctuary for those German exiles also spoke to his altruism. But it was also personal. By virtue of his Jewish mother, Niels Bohr was Jewish by heritage, if not through religious belief.

Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE), set up in 1940 with instructions from Winston Churchill to “set Europe ablaze” through sedition and sabotage, had first tried to prompt Bohr’s departure from Denmark in 1943 by sending a secret agent to the scientist’s home. Bohr’s polite rejection of London’s invitation was hidden beneath the stamps stuck to three separate postcards. Next time, SOE sent a written message, along with detailed instructions:

“A small hole to a depth of 4mm has been bored in the two keys. The holes were plugged up and concealed after the message was inserted. Professor Bohr should gently file the keys at the point indicated until the hole appears. The message can then be syringed or floated out onto a micro-slide.”

The message inside from Bohr’s friend Professor James Chadwick of Liverpool University was the size of a grain of sand and contained in a hole the width of a pinhead and had to be deciphered using a 600-power lens microscope. Chadwick urged him to leave Denmark for the United Kingdom, alluding to “a particular problem in which your assistance would be of the greatest help.”

Chadwick, his fellow Nobel Laureate for his discovery of the neutron, was leading Britain’s research into the atomic bomb.

Again, Bohr politely declined, feeling he could do more good in occupied Denmark, but he was in no doubt about the nature of the “particular problem” his friend alluded to. He just didn’t believe that given the current state of the art, an atomic bomb was feasible.

Two months later Bohr reported to Chadwick that new information had convinced him that Germany had established the means to develop a nuclear reactor using uranium and heavy water. But as the British scientist prepared to take on a new role as head of the British Mission to the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, it still wasn’t enough to persuade the ‘Great Dane,’ as he was known to SOE, to leave Copenhagen.

It wasn’t until a Danish woman working for the Gestapo saw an order for Bohr’s arrest and tipped off Bohr’s brother, Harald, that the physicist finally accepted that he had to go. Evidence of imminent action by the Nazis against Denmark’s Jewish community and the threat to him specifically was now impossible to ignore. Senior SS personnel poured into Copenhagen. A large German ship, the Wartheland, was alongside harbor, ready to carry as many of the country’s 7,000 Jews as could be packed in.

Bohr and his wife, Margarethe, left their home at the Carlsberg brewery estate within hours of the tip-off from Harald. As they slipped out of the back of their house a Nazi snatch squad was already on its way. When the couple later crawled on all-fours from a beach hut to a waiting boat, the most famous man in Denmark had with him a single bag, a beer bottle full of heavy water retrieved from the lab, and a sketch purporting to be of the Nazi’s reactor design. There had been no time to gather any more possessions before being smuggled across the strait to Sweden.

Niels and Margarethe Bohr may have thought that, with their arrival in Malmø, they were safe from the clutches of the Nazis, but that was neither how the Gestapo nor Danish Army intelligence saw the situation.

Like Madrid, Lisbon, or Casablanca, the capital of neutral Sweden was a hotbed of wartime intrigue, with spies from intelligence agencies from around the world operating side-by-side all competing for advantage. Secrets, lies, treachery, and deception were all common currency in Stockholm, and cutouts, agents, safe houses, dead drops, surveillance, and ciphers were the means by which they were traded. And with the arrival of the world’s most celebrated nuclear physicist, they had a prize worth playing for.

At first, the Swedish authorities were reluctant to acknowledge that Bohr was at risk of abduction or assassination, telling the Danish Army captain charged with his protection, “This is Stockholm, not Chicago.”

When it came to ruthlessness and brutality, the officer replied, there was no gangster that could compare to the Gestapo, and that “if anything happens to the professor it will be a disgrace to your country.” The captain never left Bohr’s side while he was in Sweden. But from now on, he was also joined by three armed Swedish secret police. Arriving in Stockholm, Bohr was bundled from a taxi into a house owned by Swedish intelligence, led through the attics to the other side of the building, and met by a second taxi, which took him to a safe house.

Three days later, the Nazis moved against Denmark’s Jews as planned, but it was already too late. Alerted, like Bohr, to the imminent danger, they were taken in, hidden, and, over time, evacuated by their countrymen. Sweden, after lobbying from Bohr himself, agreed to take them all in. Of Denmark’s 7,000 or so Jews, just 284 of the weakest and most vulnerable had been arrested.

It wasn’t even enough, remarked a crestfallen Nazi official “to justify the dispatch of a train to the concentration camp.”

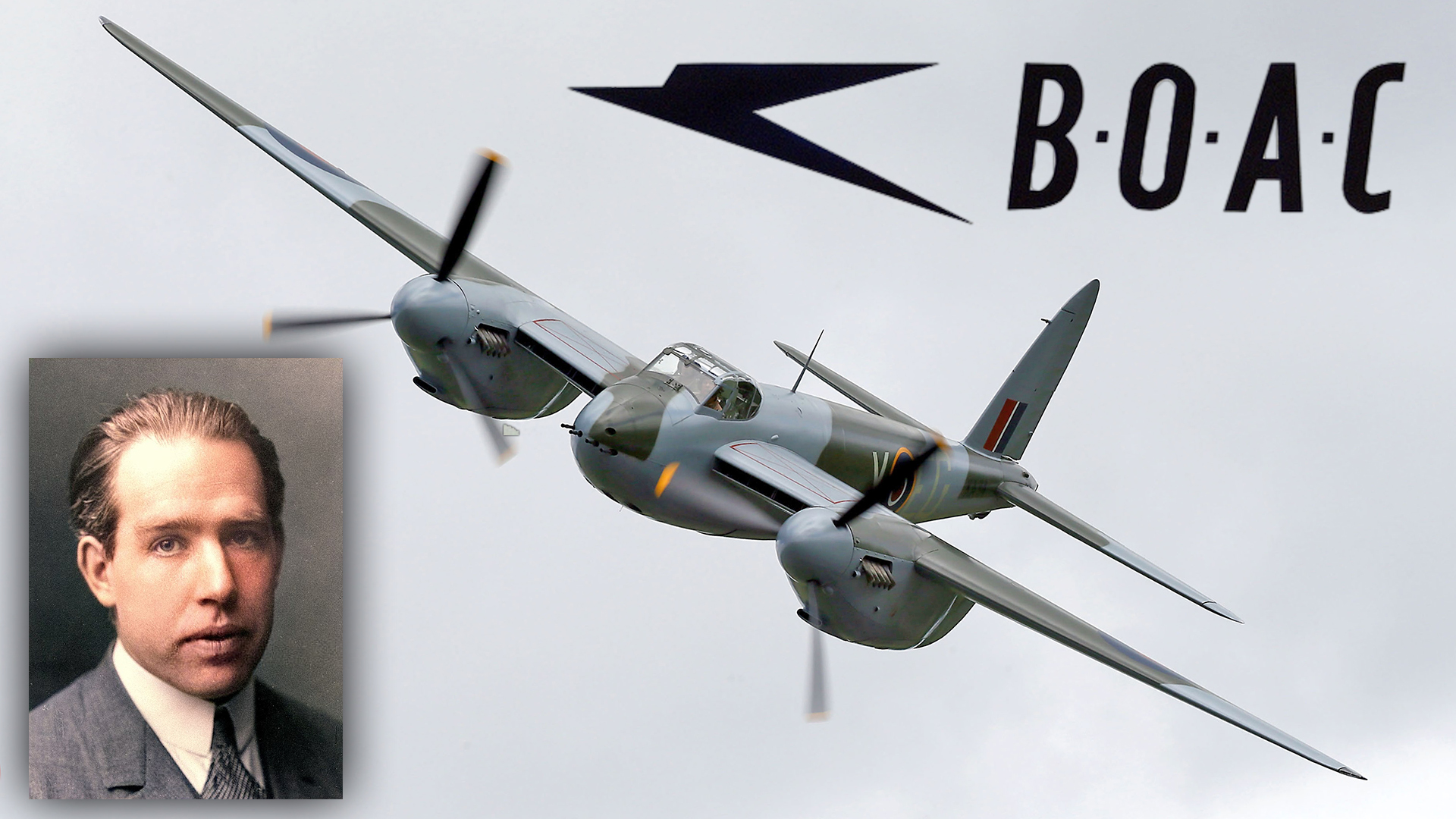

For Bohr himself to reach ultimate safety, he would now be relying on the ‘Stockholm Express.’ And, despite the name, it was not a train, but one of a small fleet of unarmed de Havilland Mosquito aircraft that, operated by British Airways’ precursor, BOAC — the British Overseas Airways Corporation — ran the gauntlet of Luftwaffe night-fighters to carry VIP passengers between RAF Leuchars in Scotland and Sweden’s Bromma Airport. Those passengers rode in the claustrophobic confines of the Masquitos’ felt-lined bomb bays. The flight nearly killed Bohr. And for that, the Mosquito’s peerless performance was to blame. That bundling a VIP into the belly of a warplane was even an option was all down to ball bearings.

For 35 years, the Swedish company SKF had led the world in the production of quality ball bearings, opening factories in the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and the United States. But with the advent of World War II, their plant in Luton, England, despite working day and night, couldn’t keep up with demand.

Each Avro Lancaster bomber for the RAF required over 175 pounds of quality ball bearings and these aircraft were rolling off the production line at a rate of around 25 a week. But there were also Spitfires, Hurricanes, and plenty more besides. Britain had a huge variety of aircraft types in production, powered by a wide variety of different engines, and all required ball bearings of their own. Nor was it just aircraft. Tanks, armored cars, warships, and anti-aircraft guns all needed ball bearings. In fact, there were very few pieces of complex military machinery that didn’t. And that, of course, included the Merlin-engined Mosquito itself.

SOE ships carrying Swedish ball bearings first successfully ran the German blockade of the Skagerrak — the strait providing access between the North Sea and Sweden — in 1941. Since June 1942, though, BOAC had been running semi-regular courier flights along the 500-mile route between RAF Leuchars and Stockholm. The airbridge, so critical to both British intelligence and war industry, crossed some of the most hostile and heavily defended skies in the world, yet BOAC had struggled to find an aircraft to serve its needs.

To begin with, the airline was given cast-off Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys. Slow and vulnerable, the obsolete RAF bombers were soon dispensed with in favor of new types acquired from the United States, small Lockheed Lodestars and Hudsons and a one-off, St. Louis, the first prototype of the new Curtiss C-46 Commando transport. The C-46 was capable of carrying heavy loads but remained vulnerable to the Luftwaffe. So too were the Douglas DC-3s that replaced it in the spring of 1943.

At Leuchars, BOAC was very firmly of the view that “the Skagerrak is no place for a Dak” — a reference to the vulnerability of the Dakota, as the DC-3/C-47 was known in British service. But in the spring of 1943, the pressure to keep up the flights only intensified with a telegram from the British Minister in Stockholm, Sir Victor Mallett:

“Since the need for at least 100 tons of bearings is desperate I recommend that risks should be taken as in any other wartime operation and that freight aircraft without passengers should fly regardless of bright nights throughout the summer months. If the Germans take to shooting them down the position can be reconsidered and at the worst, we will have lost one or two Dakotas and crews.”

BOAC disagreed and, after trialing an alternative route to Sweden, concluded in a report that what was required was “an aircraft with great performance — speed, higher ceiling, and more endurance.”

When, in 1938, as the prospect of war loomed over Europe, Geoffrey de Havilland first suggested the idea of a lightweight twin-engine bomber to the U.K. Air Ministry he was met with little enthusiasm. Undeterred, he decided that his company would build it anyway. And, if the new machine was built from wood, he knew he would not only be able to get it into production much more quickly than a metal design but would also avoid making any demand on vital supplies of the aluminum required to build every other military aircraft. In top secret, on the grounds of a moated stately home near St. Albans, north of London, his team got to work on a prototype.

They were fortunate that despite the Air Ministry’s skepticism their efforts enjoyed determined and far-sighted support from Air Marshal Wilfred Freeman, the man responsible for research, development, and production of new aircraft for the RAF. Impressed as a young pilot in the Royal Flying Corps (the RAF’s immediate successor) by the performance of an earlier de Havilland bomber design, Freeman circumvented the objections of Bomber Command to the notion of an unarmed bomber by ordering 50 of de Havilland’s sleek new Mosquitos to fulfill a separate RAF requirement for high-flying spyplanes.

Powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, the Mosquito was capable of flying to Berlin and back with the same 4,000-pound bombload as Boeing’s B-17 Flying Fortress yet flown by a crew of two instead of 10.

Following a remarkable flying display laid on for Gen. Hap Arnold, the head of the United States Army Air Corps, in April 1941, he rated it “outstanding” and insisted on taking a set of the blueprints home with him. Three months later, in the same week that it entered frontline service, a Mosquito recorded a top speed of 433 miles per hour at a time when the RAF’s top fighter, the Spitfire Mk V, topped out at 370 miles per hour. Suddenly everyone wanted the Mosquito and because of its unique wood and glue construction, furniture factories, cabinetmakers, and musical instrument manufacturers around Britain were able to put their carpentry-skilled workforces to work helping keep up with demand.

After first entering RAF service with a photo-reconnaissance unit in the summer of 1941, the first Mosquito bomber squadron formed a few months later. No. 105 Squadron’s operations remained classified for nearly a year until, in September 1942, after a low-level raid on a Gestapo HQ in Oslo, the Mosquito’s existence was revealed to the public in enthusiastic reports that noted its ability to “outpace the latest Focke-Wulf [Fw 190].”

And that was exactly what BOAC needed.

The first BOAC machine completed the ball-bearing run to Sweden in February 1943. Although not immune to the attentions of the German fighter squadrons that pincered the route, the Mosquitos, their camouflaged wings overpainted top and bottom with their civilian registration in huge letters and the airline’s iconic ‘speedbird’ logo on the nose, at least loaded the odds in favor of the airline pilots.

A single Mosquito could carry a load of 1,400 pounds of Swedish ball bearings packed in cases and stowed in the bomb bay, but its speed meant it could complete two or even three runs between Leuchars and Stockholm in a single night. In June of 1943, the airline’s Mosquito fleet completed 30 round trips to help chip away at Britain’s ball-bearing deficit, but their greater contribution was made through a single, game-changing flight at the end of the month.

Henry Waring and Ville Siberg had been kicking their heels in St. Andrews, on Scotland’s east coast, for nearly a week. Waring, a representative of the British Iron and Steel Corps, and his colleague, who ran SKF’s Luton factory, knew valuable time was being wasted. Ball bearings from neutral Sweden were supplied on a first-come, first-served basis and it was understood in London that the Germans, after Allied bombing of their own ball-bearing factories, were on the verge of placing a large order. Twice Waring phoned London urging action but was told that long, hot summer days and a complete lack of cloud cover meant attempting the flight in the waiting Lockheed 14 would be suicide.

Waring was sunbathing by the swimming pool when, on June 24, an RAF driver pulled up at the hotel. Still in his swimming trunks, Waring was taken to Leuchars and informed that he and Siberg would be traveling to Sweden that night in a pair of hastily adapted BOAC Mosquitos.

Each fortified by a stiff whisky before departure, the two businessmen reached Bromma just hours before the German negotiating team to secure SKF’s ball bearings for the Allies, and, as well as catering for British requirements, also deliberately placed orders for gauges they believed were in short supply in the Reich. Their safe delivery was recorded on the freight manifest as “one package Waring, one package Siberg.”

Geoffrey de Havilland once wrote that “if the size is right, the aeroplane becomes very versatile.” But the Mosquito had a sort of Goldilocks quality to it. It could do anything. Doctrine has it that there are four roles of air power: control of the air; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; attack; and mobility. Broadly speaking, an air force requires fighters, spyplanes, bombers, and transport aircraft to perform these tasks, each usually requiring very different characteristics in an airframe. Prior to 1943, though, the Mosquito had already made its mark as an exceptional example of the first three.

In going on to drop a total of nearly 27,000 tons of bombs on the enemy, Mosquitos suffered fewer losses per thousand sorties than any other aircraft in Bomber Command. And so accurate were they that, after the campaign to destroy V-1 flying-bomb launch sites in the autumn of 1942, records showed that Mosquito crews required less than a quarter of the tonnage of bombs to destroy each target than the next most effective bomber. There were single nights on either side of D-Day when Mosquito fighter-bombers would destroy nearly a thousand separate pieces of German motor transport.

As heavily armed eight-gun fighters — especially as radar-equipped night-fighters — Mosquitos shot down over 800 enemy aircraft. Such was the fear that they induced within the Luftwaffe in the latter stages of the war as they loitered around German airfields after dark, ready to pounce on anything coming in or out, that the term Moskitopanik was coined.

Flying photo-reconnaissance missions, Mosquitos crisscrossed Europe with near impunity gathering critical photographic intelligence that, among other things, helped delay the threat from Hitler’s V-2 ballistic missile. In assuming the mantle of airliner/transport for BOAC between Leuchars and Stockholm, the Mosquito became perhaps the only machine in history to successfully combine all four of these essential roles.

In the six months that followed Waring and Viberg’s flight, Mosquitos flew another 129 round trips to Sweden and hauled back over 100 tons of ball bearings. But it was the human cargoes they carried to and from Scandinavia that really distinguished the British and Norwegian civilian pilots and radio operators employed by BOAC. As well as maintaining the flow of intelligence and personnel to and from Sweden, and by extension, Denmark, they were also responsible for repatriating downed Allied aircrews, many of whom had been spirited out of Denmark to Sweden by local resistance groups.

A little before 6:30 a.m. at Bromma Airport on October 6, 1943, the crew of BOAC Mosquito FB.VI G-AGGG installed Niels Bohr in the bomb bay and briefed him on how to use the intercom and oxygen system. They said they would tell him when he was required to switch it on. He was given flares and a parachute in case they had to abandon the aircraft, then sealed into the claustrophobically compact space for the duration of the two-and-a-half-hour flight.

Climbing west through 15,000 feet towards the thin air of what mountaineers call the death zone near 25,000 feet, the BOAC crew was confident that, behind them, Bohr would follow his instructions. Unknown to them, the leather flying helmet that contained his intercom didn’t fit easily over the scientist’s large head, so he couldn’t hear them. Nor did Bohr, who could be remarkably unworldly, properly understand how to use the oxygen.

When the radio operator asked how he was getting on there was no answer from the bomb bay. He feared that Bohr had passed out through oxygen starvation. But until G-AGGG had swept through the jaws of the German air defenses ranged to the north and south, they had to stay high.

Two and half hours after taking off from Bromma, after completing the final leg of the journey low over the North Sea, the Mosquito FB.VI landed at RAF Leuchars and taxied towards an anxious crowd waiting by the terminal. Where, to their great relief, the Great Dane, weak but alive, was liberated from the belly of the aircraft.

The following month Bohr sailed for America, arriving at Los Alamos to join the Manhattan Project in the new year. Here, as historian Alex Wellerstein writes, Bohr’s contribution to building the first functional nuclear devices was highly significant, although subsequently underplayed.

Meanwhile, as a fighter, bomber, and spyplane, de Havilland’s ‘Wooden Wonder’ enjoyed a near-legendary reputation and established itself as something of a bête noire to Hermann Göring, commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe.

The string of daring low-level Mosquito raids against pinpoint targets across occupied Europe that captured the imagination of the public inspired the 1964 film 633 Squadron, which in turn provided inspiration for the X-Wing’s trench-run attack against the Death Star in Star Wars.

But, now almost forgotten, BOAC’s small fleet of unarmed couriers, more Millennium Falcon than X-Wing, made a crucial contribution of their own, flying vital personnel, cargo, and intelligence to and from Sweden. Completing their own Kessel Run over 520 times before the war’s end — on one occasion in early 1944, three times in a single night — the unarmed speedsters suffered losses due to bad weather and bad luck, but not one, despite coming under attack, was ever believed to have been lost to the Luftwaffe.

Perhaps, though, that brief, seemingly insignificant scene in Oppenheimer will be as close as they ever get to movie stardom of their own.

Mosquito: The RAF’s Legendary Wooden Wonder and its Most Extraordinary Mission by Rowland White is published by Bantam Books.

Contact the editor: thomas@thedrive.com