The Supermarine Spitfire, which first took to the air 85 years ago today, is one of the few aircraft that can justifiably be termed iconic. While this classic fighter’s service in the hands of the U.K. Royal Air Force and its Commonwealth allies, and even with the U.S. Army Air Forces, has been recounted in numerous books, articles, movies, and other media, it’s far less well known that it was also taken to war by the U.S. Navy.

The Spitfire’s exploits in World War II have made it a symbol of that conflict, and of its contribution to the heroic defense of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in 1940, in particular. As the tide of the war turned, it helped lead the Allied charge into Nazi-occupied Europe, which is where the U.S. Navy entered the Spitfire story.

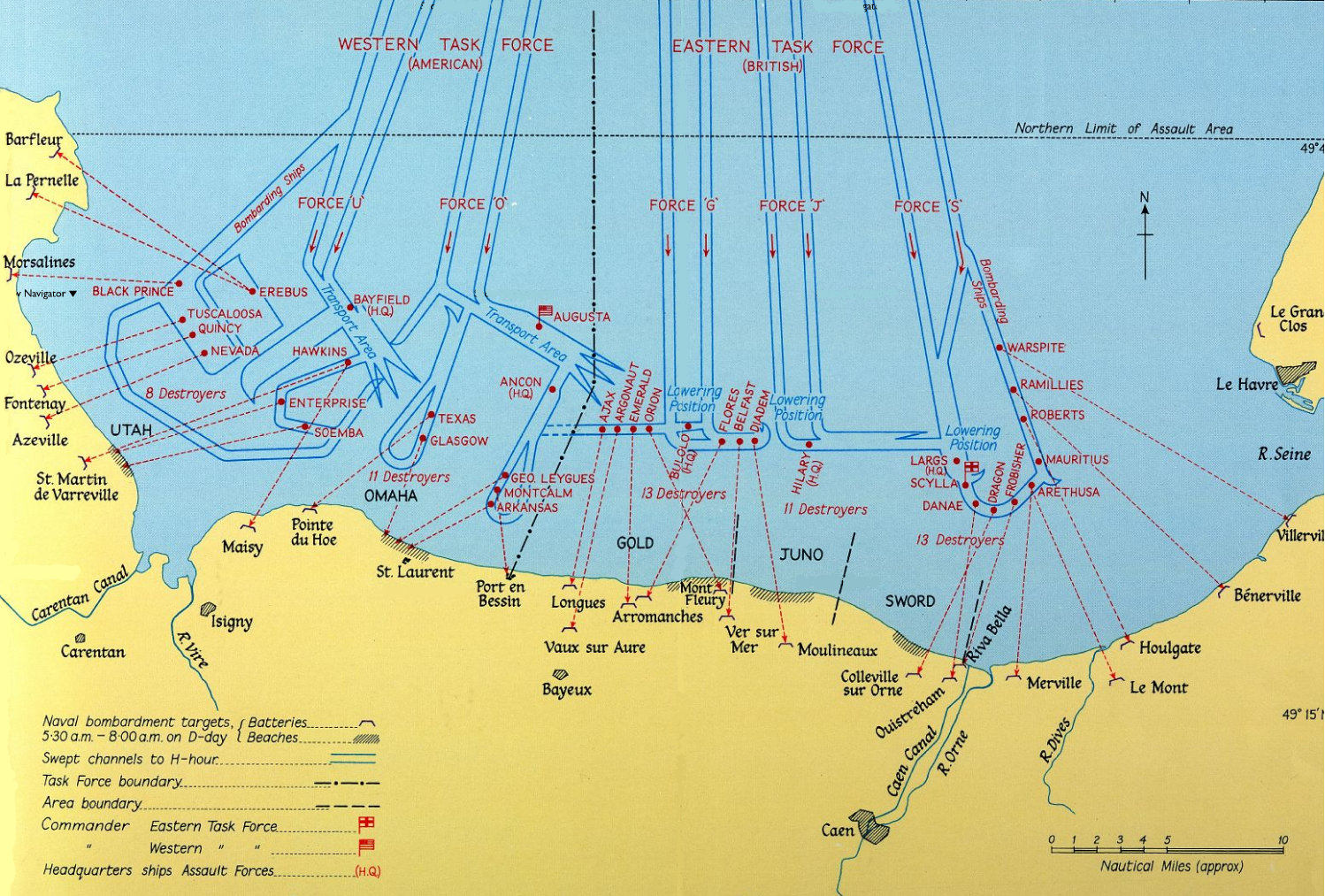

On June 6, 1944, the biggest amphibious invasion force in history was assembled for D-Day, poised to begin the grueling work of liberating western Europe. The Navy, by then, had proven the ascendancy of the aircraft carrier as the ultimate arbiter of naval warfare, but it contributed none of these vessels to the Normandy landings.

Instead, Naval Aviation was on hand to operate over the beachhead in support of the battleships and cruisers that would blast German positions along the French coast as the Allies headed ashore. This was the “air spotting” mission and it was traditionally provided by floatplanes, two or three of which could be launched from these warships by catapult, before recovering alongside after a sea landing. Their job was to observe the targets of naval artillery to see where the projectiles were landing, transmitting their observations back by radio so the guns could be corrected accordingly. Additionally, they could also work more like forward air controllers, reporting developments on the battlefield, to help neutralize counterattacks.

Up until then, the air spotting task had been handled by the biplane Curtiss SOC Seagull and the monoplane Vought OS2U Kingfisher, which were rugged and reliable, but which were considered ill-equipped to defend themselves over the beachhead, where they could meet the latest variants of the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighters. During operations in the Mediterranean in 1943, the SOC and OS2U had been shown to be vulnerable to fighter attack, and efforts were made to retrain the Navy’s spotter pilots to handle fighters like the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk or North American P-51 Mustang, which would give them the chance to fight back.

However, rather than getting their hands on any of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ (USAAF) latest single-engine fighters, it was decided that 17 pilots from Cruiser Scouting Squadrons (VCS) and Observation Squadrons (VO) assigned to battleships and cruisers would convert to ex-Royal Air Force Spitfire Mk Vb fighters. Having been introduced to service in 1941, these were hardly state-of-the-art by mid-1944 but were armed with a pair of 20mm cannons and four .303-caliber machine guns for useful defensive firepower.

The aviators were brought together as VCS-7 (although some sources state that VOS-7 was the correct designation, contemporary accounts refute this). Regardless, available evidence suggests this was the only Navy squadron to ever fly the Spitfire. Perhaps, too, it was the shortest-lived Navy flying squadron.

For its part, the USAAF was already well versed with the Spitfire, its units having taken it into battle during the invasion of North Arica in November 1942. Once they started to come back to England, they traded their war-weary British fighters for P-51s and Lockheed P-38 Lightnings. The remaining Army Spitfires were turned over to the 67th Tactical Observation Group, later the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group, part of the Ninth Air Force. The 67th used the aircraft for artillery spotting, weather and photo-reconnaissance, and bomb damage assessment. They also flew daring low-level pre-D-Day invasion missions over northern France in the reconnaissance role.

Training for the VCS-7 pilots took place with the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group, which was flying Spitfires from Middle Wallop in southern England. The naval aviators were schooled in defensive fighter tactics, aerobatics, navigation, and formation flying, as well as their primary spotting role.

On May 28, 1944, VCS-7 was declared operational and moved to its new home at Royal Naval Air Station (RNAS) Lee-on-Solent, on the southern English coast. Its Spitfire Mk Vb aircraft were all second-hand and wore RAF camouflage and markings; at least still one carried a kill marking below the cockpit from its previous operator. Black and white “invasion stripes” were added to wings and fuselages for easy recognition.

At this airfield were no fewer than 10 squadrons, in total, all tasked with air spotting, or for tactical reconnaissance, and comprising five from the RAF, four Royal Navy, plus VCS-7. Collectively, these formed the Air Spotting Pool, 34th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, 2nd Tactical Air Force. As well as Spitfires, these units flew the type’s carrier-borne cousin, the Seafire, plus Mustangs, and reportedly Hawker Typhoons. For D-Day itself, some of the aircraft were pooled, and VCS-7 was given Seafires and Spitfires.

Their work in the upcoming invasion would be to spot for the Western Naval Task Force, providing fire support to the U.S. troops landing at Utah and Omaha beaches, and the Eastern Naval Task Force, supporting the British landings at Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches.

For VCS-7, operations began at 04:41 AM on June 6, for the first spotting missions of Operation Overlord, as the D-Day landings were codenamed.

The tactics employed by the air spotters are described by Steven D. Hill in Spitfires of the US Navy:

Typical spotting missions utilized two aircraft. The lead plane functioned as the spotter. The wingman, or “weaver,” provided escort and protected the flight against enemy aerial attack. The clocking, or ship control, method was utilized on the majority of spotting sorties. Standard altitude for spotting missions was 6,000 feet, but poor weather forced the spotter to operate between 1,500 and 2,000 feet. Occasionally, missions were flown at even lower altitudes. Drop tanks were used to increase range. A typical spotting sortie lasted close to two hours. This provided 45 minutes on station and one hour in transit.

As it was, the Luftwaffe presence over the beachhead was not as bad as had been feared, although six or seven aircraft from Lee-on-Solent’s 34th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing were lost. Sources disagree whether these fell to anti-aircraft guns or were shot down by German fighters. Four VCS-7 pilots came under attack from Bf 109s and Fw 190s, but all emerged unscathed. It’s worth recalling too, that the Spitfire Mk Vb was, by this time, an aging model, inferior to the latest German fighters, and at least some of these particular airframes had likely seen heavy combat usage already in North Africa.

The only confirmed VCS-7 loss was to anti-aircraft gunfire, which claimed Lieutenant Richard M. Barclay of the USS Tuscaloosa (CA-37). His wingman made it back to base with severe damage to his aircraft. While Barclay’s is the only Normandy campaign loss recorded by the official VCS-7 combat report, there may have been more — other sources list a total of seven or eight of the squadron’s aircraft lost to enemy action throughout its existence, plus one loss not due to enemy action, over the course of 209 sorties. VCS-7’s own report lists 191 sorties between June 6 and 25, most of these on the first three days of the campaign.

One of the VCS-7 pilots, Ensign Robert J. Adams, reportedly became the first Naval aviator to land in France after D-Day, when he landed his damaged Spitfire on an auxiliary landing field in Allied-occupied territory.

By June 26, the Allied invasion force had advanced so far into Normandy that its spearhead was out of the range of the naval guns, and VCS-7 was disbanded. The aviators went back to their ships, bringing with them nine Distinguished Flying Crosses, six Air Medals, and five Gold Stars.

Although it was only a brief, cameo appearance in the Spitfire saga, the U.S. Navy’s role in the story is one that is worth remembering, for the bravery of its pilots and their valuable contribution to the liberation of Europe, on this, the anniversary of the type’s maiden flight.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com