Britain’s King Charles recently visited the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight at RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire, in eastern England, to pay tribute to the veterans of Bomber Command, who took the air offensive to the heart of Nazi Germany during World War II. The focal point of his visit was the 80th anniversary of the legendary Dambusters raid in May 1943. This daring — and very costly — raid, which has near-iconic status in the United Kingdom, is very much how the country likes to remember Bomber Command’s contribution to victory over Hitler’s Germany. The Dambusters’ targets were dams in the industrialized Ruhr region, their aim to diminish Germany’s ability to produce armaments.

Less well-remembered is another raid, or series of raids, which took place two months later, in July 1943, 80 years ago this week. This was Operation Gomorrah, and it brought destruction on a terrifying scale to the port city of Hamburg in northern Germany.

While the bombing of Hamburg in July 1943 actually involved six separate raids, including direct cooperation by RAF Bomber Command and the U.S. Army Air Forces’ Eighth Air Force, the raid on the night of July 27-28 was the most devastating. It killed around 20,000 in a single night. By comparison, the most lethal night of the German Luftwaffe’s Blitz offensive against London in 1940-41 killed around 1,400 people. No other single Allied air attack in the European Theater of Operations during World War II would come close.

Operation Gomorrah — its name grimly appropriate, for the biblical city destroyed by God with fire and sulfur — represented a change in tactics for Bomber Command and it would also usher in new technical developments, including the use of radar-spoofing chaff countermeasures. Meanwhile, the combination of high-explosive and incendiary bombs, placed accurately over a given residential area, would introduce the world to the terror of the firestorm.

Initially, the RAF had sent its bombers against mainly industrial targets in Germany, hoping to have an impact on the production of weapons as well as hinder other war-critical functions. But at this stage, the ability of aircraft to put their bombs onto such targets with the required accuracy meant much of this was a wasted effort, taking a very heavy toll on aircrews.

The thinking of the British war-planners began to change. Where once an individual munitions factory might have been targeted, for example, the next logical step was to attack also the entire area surrounding such a factory. Finally, the target was extended to the workers that this factory relied upon. This meant launching raids against the sprawling residential areas of the cities where these civilians lived.

A joint decision by the British War Cabinet and the Air Staff in 1942 called for the targeting of “the morale of the enemy civil population — in particular the industrial workers.” The RAF would achieve this by launching massed raids against German cities with populations over 100,000. The aim of the ‘area bombing’ campaign was to kill and make homeless workers, disrupting industrial output while also sapping civilian morale — although this last one is something the Luftwaffe had singularly failed to do when targeting British civilians in 1940-41.

By 1943, Bomber Command had assembled a powerful fleet dominated by modern heavy four-engine bombers — Avro Lancaster, Handley Page Halifax, and Short Stirling — and was ready to put the new strategy into practice.

To wreak maximum havoc on city targets, it had been determined that the optimum payload comprised a mixture of high-explosive bombs and incendiaries. The larger high-explosive weapons would collapse the structures of buildings, as well as block roads, destroy water mains, and more. Densely packed incendiaries would then start fires among the wreckage.

At first, in spring 1943, the industrial areas of the Ruhr valley in the west of Germany were targeted.

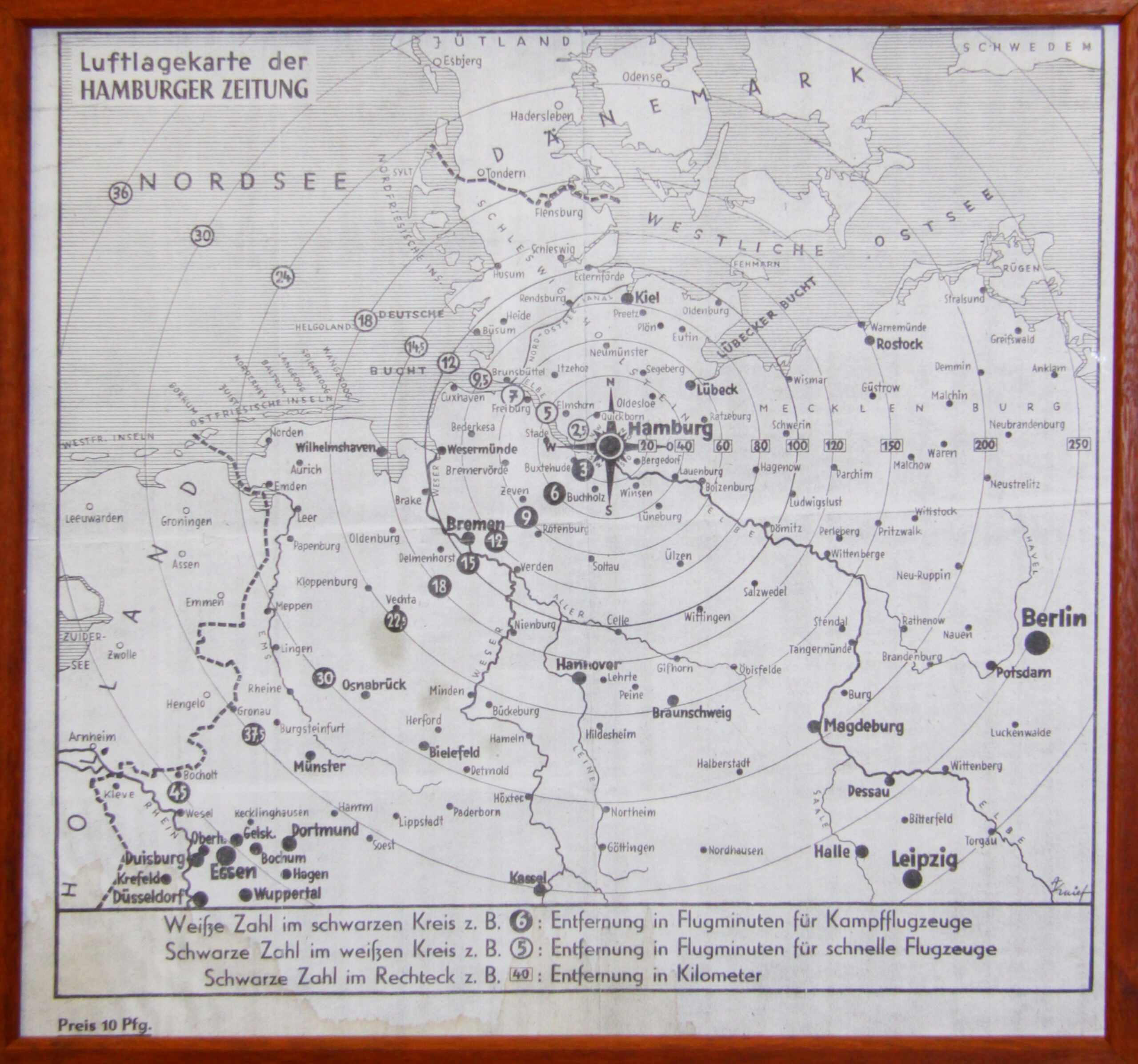

As of July 1943, it was Hamburg’s turn to experience this new type of aerial bombing. The city had been chosen, in part, because it was judged to be especially vulnerable to incendiaries.

The first night raid, on July 24-25, involved around 790 RAF bombers and saw the first use of Window, the codename for chaff, which proved highly effective, only 12 bombers being lost. The tens of thousands of strips of aluminum paper successfully confused German radars and hindered attempts to intercept or shoot down the bomber force. Remarkably, at least some of the aircrews knew nothing about Window, or how to use it, until the night of this mission.

The accuracy of the raid was enhanced by the new H2S ground-scanning radar system, which provided the bomber with navigational cues based on high-contrast landmarks below. This would be particularly effective in the case of Hamburg’s River Elbe and sprawling docks.

However, on July 24-25 the bombs did not fall with the desired density of concentration, reducing their effectiveness. Around 1,500 people were killed in this first raid.

July 25 saw a day raid on Hamburg by around 120 USAAF bombers, while around 50 USAAF bombers struck again by day on the 26th. On these occasions, the target was the port, rather than residential areas and German fighters badly mauled the bomber force.

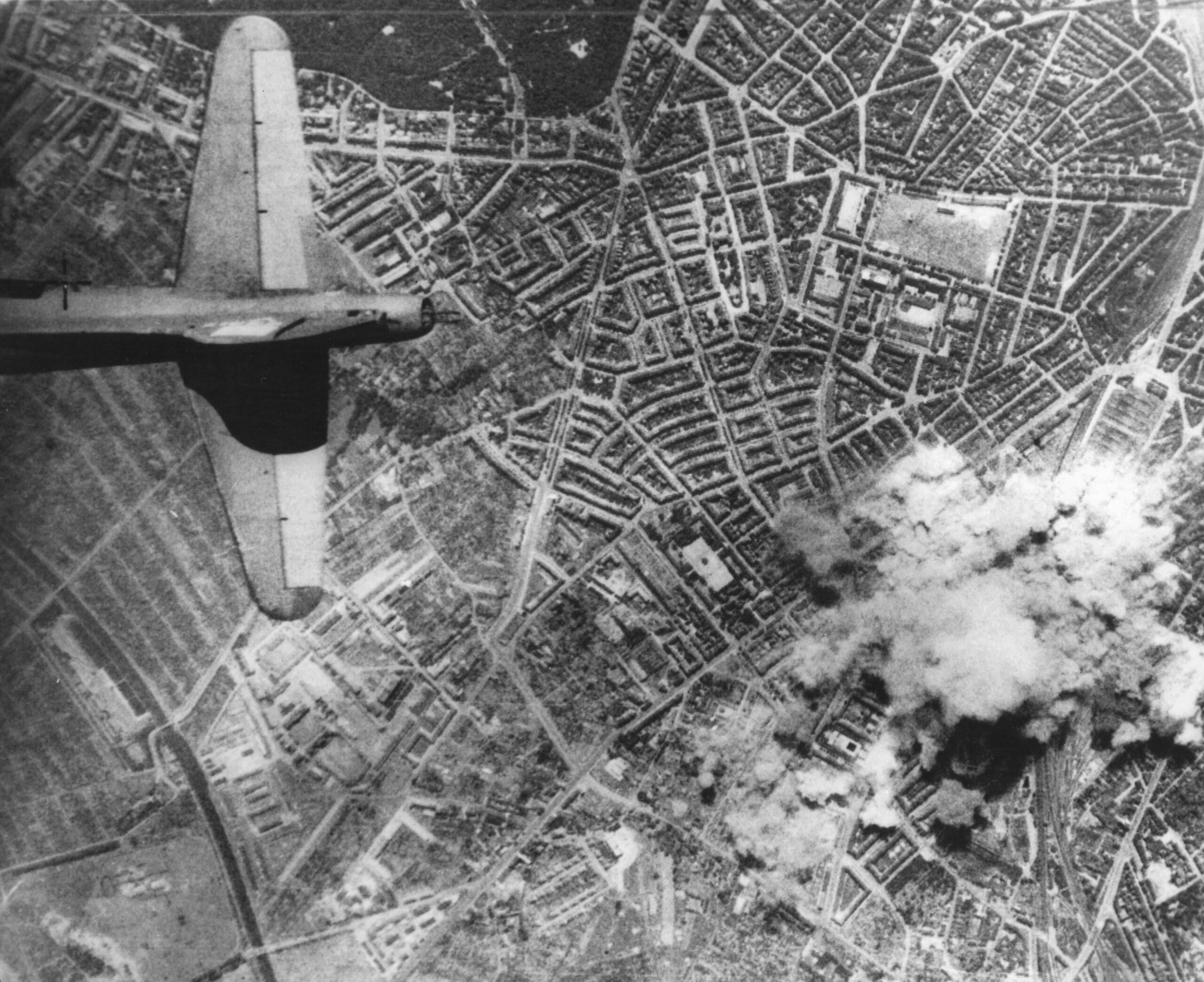

It was the night raid of July 27-28, this time involving about 780 RAF bombers, that led to the first firestorm in Hamburg, in the eastern part of the city, which was dominated by multi-story working-class housing.

The weather also conspired against the German port city. It had been a long, sultry summer, leaving everywhere very dry, and July 27 had been especially hot.

At the same time, fire crews were already engaged in tackling blazes that continued in other parts of the city, after the previous raids.

With Window again ensuring that most of the bombers got through, these aircraft started to arrive over the city shortly before 1:00 AM. This time, almost all the 2,326 tons of bombs fell in close proximity, exactly as planned.

Very rapidly, the conflagrations began to connect and, as a column of fire ripped 1,500 feet into the sky, more air was sucked up from street level, creating the inferno known as a firestorm — Feuersturm in German.

As winds reaching speeds of 150 miles per hour tore through the parts of the city affected, temperatures rose to 1,472 degrees Fahrenheit or more. The heat was so intense that glass exploded, metal became twisted, and stonework glowed a dull red.

There was very little that the already overstretched fire crews could do about it.

At times, the hellish scene bordered on the surreal, based on witnesses’ accounts. One described the sound of the blaze as like “an old church organ when someone is playing all the notes at once.” Starved of oxygen, candles began to extinguish themselves. Horses ran down the streets, the animals also on fire. People in the open were trapped in melted roads as they tried to escape. Meanwhile, anything that was unsecured was dragged toward the center of the blaze, people included.

One resident, Henni Klank, recalled escaping to an underground shelter, together with her husband and baby once the curtains in their apartment caught fire and the ceiling began to crack.

“At this moment something snapped in a neighbor and, caught up in a panic, he took his bed cover and wanted out,” Klank recalled. “None of us could stop him. We saw him still, but only as a living torch carried by the firestorm, flying through the air.”

A similar account was provided by Paul Peters, another Hamburg resident: “The firestorm was so strong that hats were torn off heads and whirled through the air like burning fireballs,” he later wrote. “Even little children, running around alone, were bodily picked up from the ground and thrown through the air.”

Shelters offered little in the way of refuge, however, due to the intensity of the fires above. Many residents suffocated, as the air was sucked out of the shelters, or were otherwise cooked alive.

An area measuring around 4 square miles was almost entirely destroyed by the firestorm, although the damage from this raid extended over roughly 12 square miles.

At its worst, the raid left 16,000 apartment buildings, home to nearly 450,000 people, on fire.

Even the aircrews above were not insulated entirely from what was happening in the city.

Some reported that they could feel the heat, and even the smell of roasting flesh, while their aircraft were becoming caked with soot.

“The blaze was unimaginable,” Flying Officer Trevor Timperley recalled. He served with an H2S-equipped Lancaster Pathfinder squadron, tasked with finding and marking the target for the bombers that followed. “I remember saying to the navigator, who was always engrossed with his charts: ‘For Christ’s sake, Smithy, come and have a look at this. You’ll never see the like of it again!’”

“But Hamburg raised for me for the first time the ethics of bombing,” Timperley added.

For others, the priority was simply to complete their assigned missions — and survive.

Air Gunner Douglas Fry, a mid-upper gunner on a Stirling, remembered the raid as: “Brilliant, better than [earlier raids]. The fires were incredibly fierce; you couldn’t see a black spot amongst this huge sheet of flame which covered acres and acres.”

Fry added: “We didn’t know about the firestorm — we just knew the target was well alight, which meant a good raid.”

Local authorities ordered the evacuation of Hamburg on July 28, before the city was visited by another firestorm on the night of July 29-30, the result of a raid by around 770 RAF bombers.

The last of the raids in this series took place on August 2-3. This was less successful, with around 740 RAF bombers becoming scattered after encountering bad weather.

By the time Operation Gomorrah ended, between 34,000 and 43,000 people had been killed in the six raids. With around half of all homes in the city destroyed, approximately 1 million of the population of 1.7 million were forced to flee.

The following tweet thread , from historian Alan Allport, is well worth looking at for a concise summary of the Gomorrah raids:

Ultimately, the raids on Hamburg would not be repeated in terms of scale or brutal effectiveness. As the RAF turned to targets further away, the raids became more costly once again, while the Germans also made moves to improve their anti-aircraft defenses.

Of course, diverting fighter aircraft and anti-aircraft artillery to German cities meant fewer weapons elsewhere, including on the front lines, although the overall effectiveness of the area bombing campaign against German cities remains a subject of debate.

But for Air Marshal Arthur Harris, the chief of Bomber Command, the purpose of the campaign was very clear, as he expressed in October 1943:

“The aim of the Combined Bomber Offensive … should be unambiguously stated [as] the destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers, and the disruption of civilized life throughout Germany … The destruction of houses, public utilities, transport and lives, the creation of a refugee problem on an unprecedented scale, and the breakdown of morale both at home and at the battle fronts by fear of extended and intensified bombing, are accepted and intended aims of our bombing policy. They are not by-products of attempts to hit factories.”

While Bomber Command did continue raids of this kind until the end of the war, including against Dresden, it was becoming increasingly clear that more accurate attacks against specific targets were possible — and, if prioritized, would almost certainly have been more effective and less costly in terms of aircrews lost.

The reason that the legacy of Operation Gomorrah sits uneasily with memories of RAF Bomber Command, and its World War II missions, is clear. This was an operation squarely intended to kill as many people — civilians — as possible, in the most efficient way. Very similar firebombing tactics would later be put to use by the USAAF over Japan, with even greater loss of civilian life.

In his comments at RAF Coningsby yesterday, King Charles addressed the problematic nature of the Allied bombing campaign directed specifically against German cities:

“We’re criticized by people who would not have come into existence if we had lost the war,” he said, accurately.

He continued: “And this is the most important thing, the objective of Bomber Command was to destroy the German capability of attacking us, that, and nothing more. We weren’t interested in killing civilians, we were only interested in destroying their cities that were producing armaments and other weapons to be used against us. And by and large, I think Bomber Command did a very good job.”

While there’s no doubt that Bomber Command made a very significant contribution to winning World War II, it came at the cost of not only more than 50,000 of the command’s own aircrew, but also as many as 600,000 German civilians killed in bombing raids. Very clearly, war planners were interested in killing civilians. As for the parts of Hamburg specifically targeted in July 1943, they were not chosen for “producing armaments and other weapons,” but because they housed civilian workers and their families.

The moral implications of this and similar decisions, and the question of how this bombing campaign affected the course of the war, should not be ignored.

The 80th anniversary of Operation Gomorrah is perhaps as good a time as any to revisit this less palatable part of Bomber Command’s history and finally look at it in a more balanced way.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com