The fortieth anniversary of the Falklands War, which ended on this day, in 1982, with the final surrender of Argentine forces to the British, has seen many reflect upon the ten-week conflict fought in the South Atlantic. In the process, the stark reality of the United Kingdom fighting a war it was hardly prepared for, and successfully returning the islands to British control, has provided a chance to recall some of the many episodes of bravery, endurance, innovation, resistance, and disaster. One episode that encompassed many those and more was the loss of a special forces Sea King helicopter in the icy waters on May 19, 1982 — the biggest loss of life in a single day for the elite Special Air Service (SAS) since World War II.

On the eve of the anniversary of the Argentine surrender, The War Zone spoke to Mark ‘Splash’ Aston, one of the nine survivors of the Sea King incident that claimed the lives of 22 of their comrades, 18 of them from the SAS.

Before looking at some of the triumphs and tragedies of Splash’s SAS contingent in the South Atlantic, the veteran of the special forces reflected on the status of the regiment at that time, in the wake of the highly public Iranian Embassy siege in London. During that episode, SAS troops stormed the embassy after gunmen had overrun it and taken hostages. All this played out in front of the world’s media. This had done much to bring the regiment’s work to wider attention, although only one of its four squadrons was actually on standby for counter-terrorism work.

Splash explained: “The SAS is actually what we call a green unit — we train for general war and the counter-terrorism bit is just a small part of what we do … We just went straight away and did it. There was no build-up training, nothing like that. We just went down and got on with what we normally do.”

What the SAS did, in this case, included inserting small reconnaissance teams onto the still-occupied islands ahead of regular British soldiers, primarily using Sea Kings to fly in and out under cover of darkness and as low as possible to evade Argentine radar. SAS patrols on the Falklands would later call in highly effective airstrikes by Harrier jets. There was even a daring (and ultimately abortive) attempt to infiltrate the Argentine mainland and destroy the feared Super Etendard attack jets with their Exocet antiship missiles.

Most routine training for the SAS focused on the Soviet threat and, for Splash, in particular, that meant he was prepared for contingencies in northwest Europe. “Most of us didn’t even know where the Falklands were, to start with,” he added. “When you worked out that it was on the other side of the world, and on the bottom, near Antarctica, then we weren’t really well prepared, gear-wise.”

While Splash’s D Squadron did get its hands on more appropriate equipment, including cold-weather gear, a few weeks into the conflict, they began the war wearing their normal temperate uniforms intended for NATO’s southern flank, rather than Arctic garments found in G Squadron, with its northern flank assignment. “It was horrible to start with,” Splash recalled. “But they realized quite rapidly that we needed decent waterproofs and stuff like that. The quartermaster basically went out to a local outdoor firm and bought up all their cold-weather gear.”

Weapons-wise, the SAS also had some of their own special-issue gear, although much of what they used was similar to that used by the average British soldier. However, instead of using the standard 7.62mm Self-Loading Rifle, or SLR, the SAS was armed with the U.S.-made 5.56mm M16/AR-15 as its rifle. These were fitted with underslung grenade launchers, also a rarity in the British Army at the time. Stinger shoulder-launched missiles were made available after the United States agreed to a rapid transfer of these weapons plus training. Once captured Argentine weapons became available, Splash swapped his Armalite for a 7.62mm rifle, since he appreciated its superior stopping power.

At the beginning of the conflict, Splash was involved in Operation Paraquet, the British operation to recapture the island of South Georgia from Argentine control.

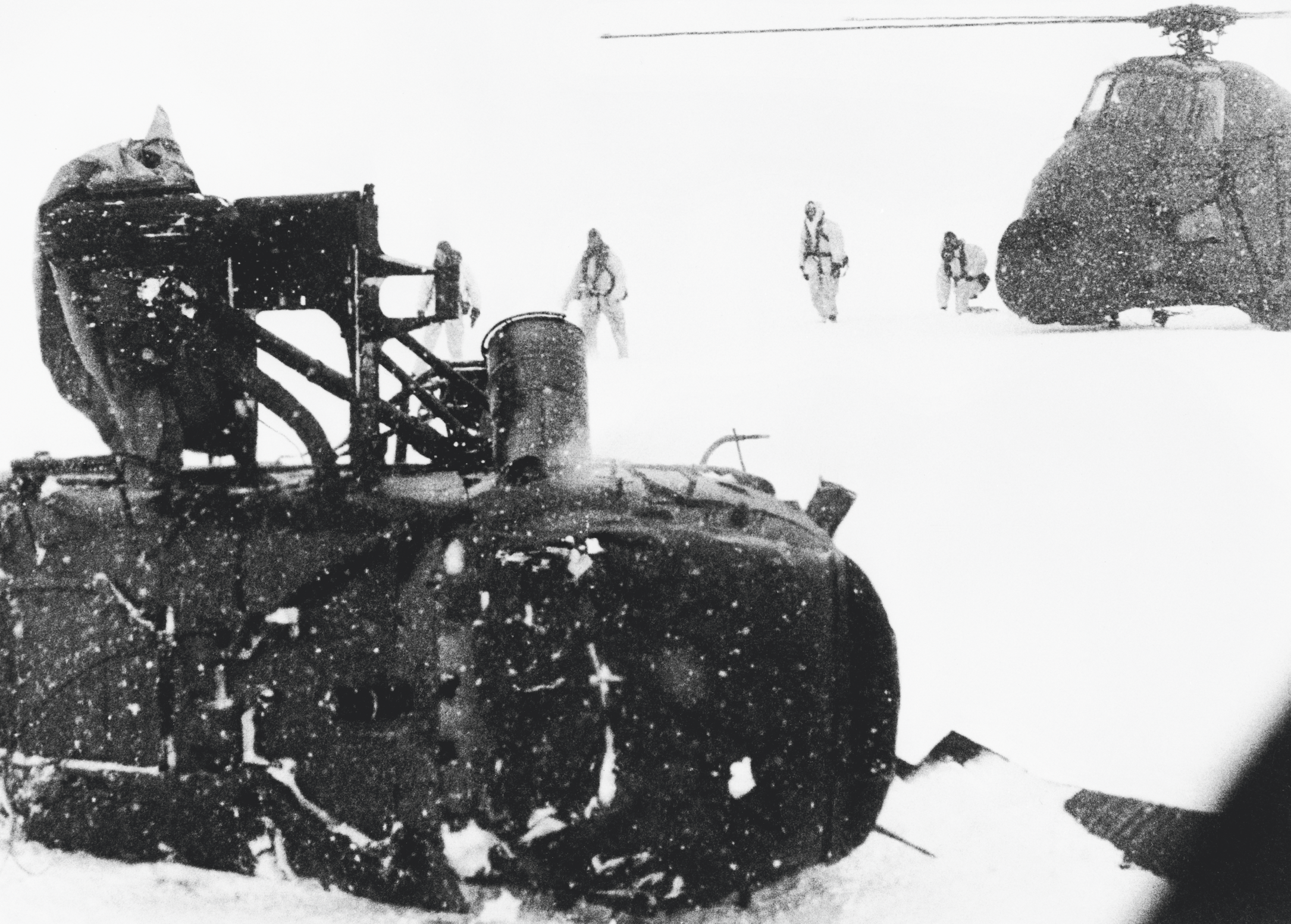

Embarked primarily aboard the replenishment oiler, RFA Tidespring, the South Georgia force consisted of Royal Marines as well as an SAS troop and members of the Special Boat Service (SBS). Although SAS and SBS troops began to land on the island’s Fortuna Glacier on April 21, this advance party had to be withdrawn as winds reached 100 miles an hour and hypothermia began to kick in. In the process, two troop-carrying Wessex Mk 5 helicopters were lost in white-out conditions.

After the first Wessex crash-landed on the glacier after the pilot became disorientated in the blizzard, it was the turn of Splash’s own aircraft, now carrying the additional troops from the first, to get into trouble. Splash described what happened next:

“His visual reference suddenly gone, our pilot instinctively pulled on the power and lifted the nose up, but it was too late. His starboard wheel clipped the side of the crevasse, tipping the Wessex sideways, digging the tips of the main rotor disc into the side of the glacier. It was a miracle that the flailing blades didn’t thrash the cab to pieces with us inside it, but the ice and snow had acted as a shock-absorbing energy damper. If the helicopter had impacted on hard ground or rock, the blades would have snapped back, and the bent metal would have chopped us into mincemeat. It all seemed to happen in slow motion, like being in a car crash, as we half slid and half bumped into the glacier’s slope. No doubt the reduced impact was due to the skill and the reactions of the pilot and the fact that the crewman had insisted that we had all strapped into our seats before takeoff. Regardless, we landed on top of one another as the airframe pitched onto its side and slid to a halt in a blur of fragmenting ice and shrieking metal.”

Splash and the others were then flown back from the glacier, aided by the tireless work of a Royal Navy crew flying an anti-submarine Wessex Mk 3 from HMS Antrim, which was impressed into the role of troop-carrier. The escape from South Georgia also saw that same Wessex make an emergency landing on the back of a ship, with 17 SAS men crammed inside a cabin that had been designed for just four anti-submarine specialists.

But this wouldn’t be Splash’s last lucky escape of this campaign.

Meanwhile, a follow-up direct assault, under naval bombardment, achieved better results on South Georgia, and on April 25 the island was back under British control, the Argentine troops there surrendering without resistance in what was the first British success of the war.

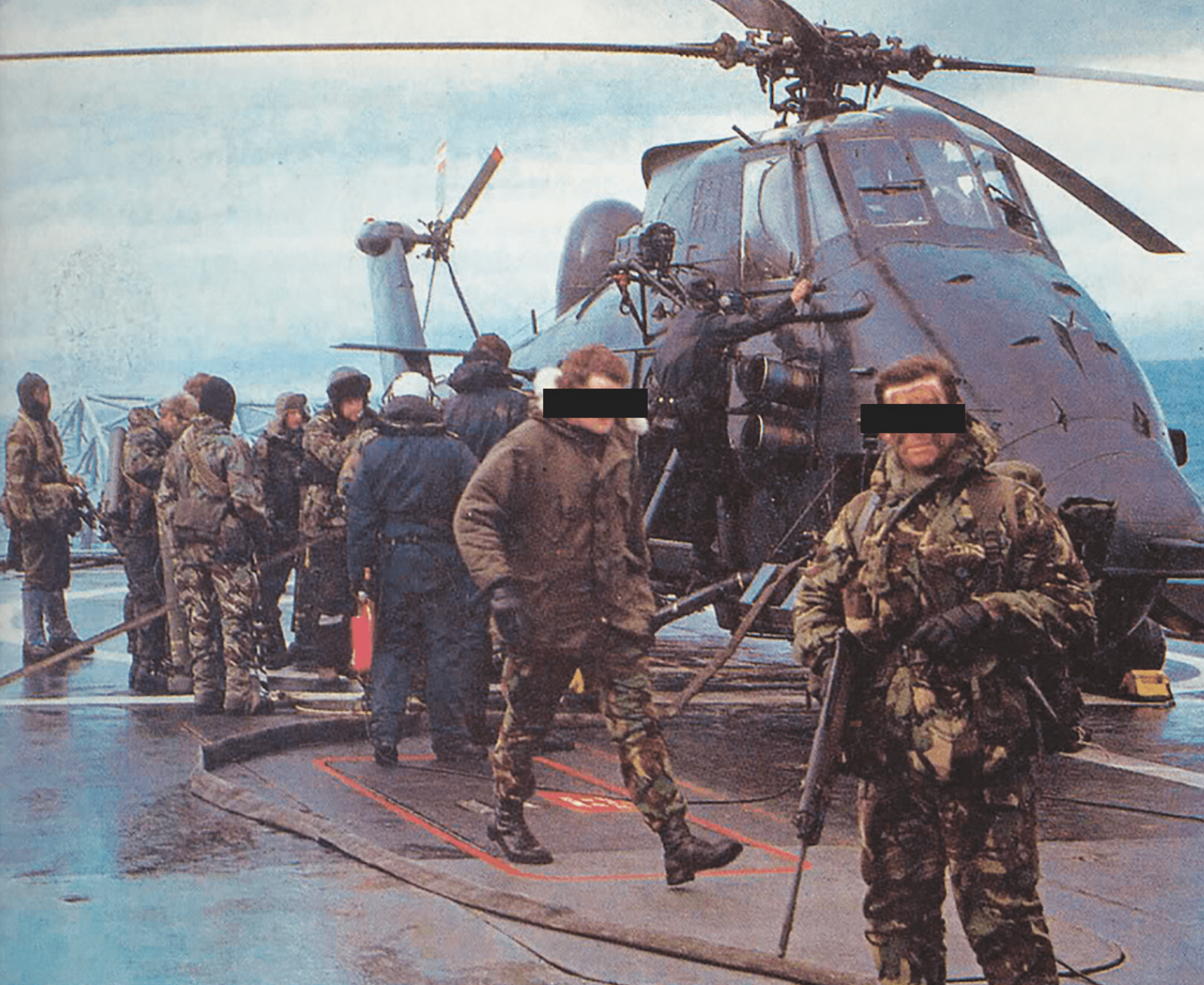

For Splash, however, perhaps the most celebrated mission he participated in was the May 15 raid on Pebble Island, a 22-mile-long island in the northwest of the Falklands archipelago. The Argentine Air Force was making use of a grass airstrip on the remote outpost, from where they could operate twin-turboprop Pucara ground-attack aircraft.

While an airstrike could have been flown from one of the Royal Navy carriers in the South Atlantic, this was judged too risky due to the chance of missing the Pucaras as well as the close proximity of civilians to the airstrip. Instead, a 42-strong SAS team was delivered by three Sea Kings through near-hurricane-force winds to knock out the Pucaras as they sat on the flight line.

Under supporting naval gunfire from the destroyer HMS Glamorgan, the SAS men successfully assaulted the airstrip, with Splash later describing the scene that awaited them there:

“A flat, open airfield lined with Argie aircraft parked along the right-hand length of a main grass strip. Other aircraft were dotted on the opposite side of the runway along two intersecting alternative takeoff strips.”

“Fucking gleaming! Nervous tension evaporated in an instant as I mentally rubbed my hands with glee.”

“There were no Argies dug in around the apron of the airfield. They may have missed their chance, but we were not about to miss ours. Parked in front of us, those aircraft were ours for the taking, and we were about to inflict the havoc we were born to wreak.”

Video footage of Pucaras in action during the Falklands War:

A combination of machine-gun fire, grenades, and explosive charges placed on the Argentine aircraft had quickly left six Pucaras as burning wrecks. The SAS also destroyed several T-34 Turbo-Mentors and a Short Skyvan transport that also shared the airstrip — 11 aircraft in all were knocked out. One British soldier was injured by an improvised explosive device, but all made it safely back to the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes before daybreak.

One of the Sea King pilots, Col. Richard Hutchings, later described the assault on Pebble Island as “the best example ever of a combined-operation special forces mission since World War II.”

A few days after Pebble Island, on May 19, Splash’s — and the regiment’s — fortunes would be turned on their head.

Shortly before regular British forces invaded the islands to end the Argentine occupation, the SAS were involved in a cross-decking operation — moving troops and equipment between warships in the task force. For Splash and his troop, this meant taking another Sea King for the roughly half-mile trip between HMS Hermes and the nearby amphibious warfare ship HMS Intrepid.

The night-time mission saw Splash’s Sea King heavily loaded with men and equipment.

“By the time I got to the door,” Splash recalled, “the helicopter looked full. Too full. Every part of the interior was jam-packed with men and equipment, from the space behind the pilots to the tailplane.”

As his thoughts turned to the beer and shower that awaited him on Intrepid, Splash suddenly became aware of “a distinct thump and an immediate winding-down of the engines. To me, it felt like an express train suddenly pulling on its brakes. I was thrown forward, and the next thing I knew was that we were in the sea and under the water.”

While the Sea King’s boat-like hull was designed to provide buoyancy in a landing on water, in this case, the helicopter slammed into the waves in an uncontrolled dive.

“The helicopter turned onto its side as it struck the surface. Its spinning rotor blades thrashed into the waves, biting deep into the water, as the weight of the roof-mounted engines rolled the airframe over and forced it beneath the rising swell. The troop door imploded in a wall of freezing white water, flooding the troop compartment from the floor to the ceiling. It all happened in an instant, but somehow I managed to snatch a lungful of air as we turned upside down and went under.”

That last gasp of air may well have been the difference between life and death for Splash, who managed to find his way out of this terrifying underwater prison.

“Each one of us was fighting with primal urgency to live in a cauldron of freezing darkness and terror. As men exhaled, the desperate sound of their last breath was attenuated through the sea-filled interior.”

Getting out of the remains of the helicopter was just the first part of Splash’s improbable survival. After squeezing his way past a maze of jagged and twisted metal and through a hole torn in the tail section of the aircraft, Splash had to grab hold of a seat cover for buoyancy and then deal with heavy swell and a sea temperature only just above freezing.

A matter of minutes longer in the water and neither Splash nor the other nine survivors would not have made it out alive. As it was, the hypothermia was kicking in and all were briefly unconscious after being pulled out of the water and onto a rigid-hull inflatable boat sent from the frigate HMS Broadsword.

To this day, the cause of the Sea King crash remains unclear, with theories that it could have been a bird strike or a mechanical failure.

Remarkably, despite a suspected broken neck, Splash’s war was not yet over. He managed to escape from the casualty evacuation ship SS Canberra and rejoin his unit, D Squadron.

“Where the fuck have you been, Splash?” was the first response from one of his comrades, on arriving back with his unit, amid looks of surprise all around. “We were about to start auctioning your kit,” his fellow soldier added.

More Falklands combat followed for Splash, among them, operations behind enemy lines operations followed, including an ambush of Argentine special forces on Mount Kent. All the while, Splash and his team had to evade enemy search patrols and cope with sub-zero temperatures.

It was at Mount Kent that Splash was particularly impressed by one of the signature weapons of the conflict, the Harrier jump-jet, in this case, flown by the Royal Air Force in its GR3 version:

“I saw the first jet scream in low between our position and Mount Challenger, filling the valley with the roar of its Pegasus Rolls-Royce engine. It swooped out of sight into the lower ground towards Stanley. The distant explosion of ordnance rolled back towards us, indicating that it had found its target, which had been called in by an unseen G Squadron patrol. The Harrier malleted an Argentine Marine company group with its cluster bombs and rockets, as the hundred-odd enemy soldiers moved into position in lower ground. It was also a remarkable piece of flying.”

Splash continued: “We couldn’t have done a lot without the air cover that we had from the Harriers. They did well. And the Navy was absolutely fantastic. We were so well looked after by them and they went through so much shit to make sure that people were in the right place at the right time, to support us.” At this time, of course, delivering air support meant a pilot essentially navigating using tactics closer to those of World War II than today. “The Harrier pilots, so I was told, had to have a stopwatch with their compass so they knew exactly when to turn and we would talk to them. The way to describe it was perhaps the last analog war.” Things changed very quickly after the conflict, however, with forward air control, in particular, quickly being brought up to date with satellite communications and other advances.

Compared to the high-visibility status of the SAS during the Iranian Embassy siege, the Falklands saw the regiment once again slip back into the shadows, a status they much preferred. Splash told The War Zone: “We were really kept in the background. No one mentioned and even the raid that was done on the airfield on Pebble Island was put down to the Marines. They didn’t mention us at all; it was good for our cover. It all started to come out afterward.”

Nevertheless, at times, the Falklands must have felt like a very personal kind of conflict for Splash, despite being 8,000 miles from home and representing just a matter of weeks in what was an impressive 39-year career, ending only in 2003. He has since returned to the islands to meet residents and reflect on the comrades he left behind there:

“I liked seeing the people we liberated. Most were kids then, but they have never forgotten what British forces did for them, and the troops who were killed in the fighting to kick the Argies back off the Falklands.”

Much the same sentiments are likely shared by most British personnel who served in the conflict, in whatever capacity. As memories fade with the passage of time, and with older veterans no longer around to tell their stories, the accounts of Splash and others take on an even greater resonance, reflecting the realities of this short and brutal war.

With thanks to Mark ‘Splash’ Aston, whose book, SAS: Sea King Down, is out now in paperback, ebook, and audiobook.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com