One of the world’s most accomplished test pilots, James E. Brown III, or “JB,” has enjoyed a glittering career, which today sees him heading up the National Test Pilot School as its president and CEO. Now, in this lecture hosted by California’s Western Museum of Flight, JB provides his captivating insights on the world’s first two stealth tactical jets — the F-117 Nighthawk and F-22 Raptor. Few are better to comment on what it’s actually like to fly these aircraft, with JB having been, at different times, chief test pilot for these programs, and having accumulated around 1,000 hours on each.

With more flight time in stealth fighters than any other pilot in the world, JB is clearly in a unique position to speak about these aircraft, both of which come from the Lockheed stable. At the same time, his job as a test pilot means he is best able to explain the ‘feel’ of these jets and their impressive capabilities. His explainers on the two aircraft feature an unusual level of detail and accessibility — the kind of presentation critical to delivering the feedback needed to understand the jet and its systems and make them even better. Precisely the job of a test pilot like JB.

First off, based on JB’s description, getting the chance to strap into a Raptor cockpit for a day can be a near-religious experience. He paints the impression of a morning sortie from Edwards Air Force Base, California in beautiful detail: “She’s cold but very good-looking in that bright light. Do the walkaround, crawl up into the cockpit, sit down in a cold ejection seat, you can feel the chill soak through the flight suit. Close the canopy, get the auxiliary power unit going. And then it’s time to start engines and you can feel these two F119 engines roar to life. It takes them about a minute to go from cold to idle RPM. You can feel the power of the airplane, now she starts to come alive, things start to warm up, the displays flicker on and you’re in your own little warm world, looking outside the hangar it’s black again … So, pull out of the hangar, out of this bright light into the dark.”

“Make the way down to the taxiway to the end of the runway, the final inspection checks are done. The crews walk around the airplane one last time, get a thumbs up. Again black, into the dark, onto the runway. And if you look to the east, you can just see a ribbon of dawn starting to happen … I could be going supersonic by the end of the runway if I chose. However, now I’m just gonna get away from the ground. Get out to about 450 knots, and then we’re maybe two-thirds of the way down a runway, stand the airplane on its tail and I’m climbing and accelerating 70-80 degrees nose-high. Riding a veritable rocket ship. I’m in the dark. And then all of a sudden: Boom! It’s daylight. I bathe in the bright sunlight of the dawn and, looking outside the airplane, the rest of the world is bathed in black.”

And, if you’re flying out of Edwards on an early morning, having previously gotten up at 3:00 A.M., a full-afterburner takeoff will not only get you airborne within 1,500 feet but also wake up everyone else on the base.

Some interesting tidbits, starting with the F-117 portion of the lecture, include:

- The stealth technology that led to the F-117 was essentially born out of a 1970s-era study that analyzed Israeli losses in the Yom Kippur War and plotted them against a potential Warsaw Pact invasion across the Central European Plain. The resulting air battle would have seen NATO “out of airplanes” in just 14 days, according to this prognosis. Surprisingly, Lockheed was not originally asked to respond to the stealth aircraft requirement that DARPA came up with to help solve this issue.

- With the A-12 and SR-71, Lockheed had actually been building aircraft with some degree of stealth and measuring their radar signatures well before DARPA got interested in this work. But it had always done this on the back of CIA money. Skunk Works head honcho Ben Rich, therefore, needed CIA backing to persuade DARPA that the company should build the Have Blue technology demonstrators that led to the F-117. We detailed this interesting reality in a recent report.

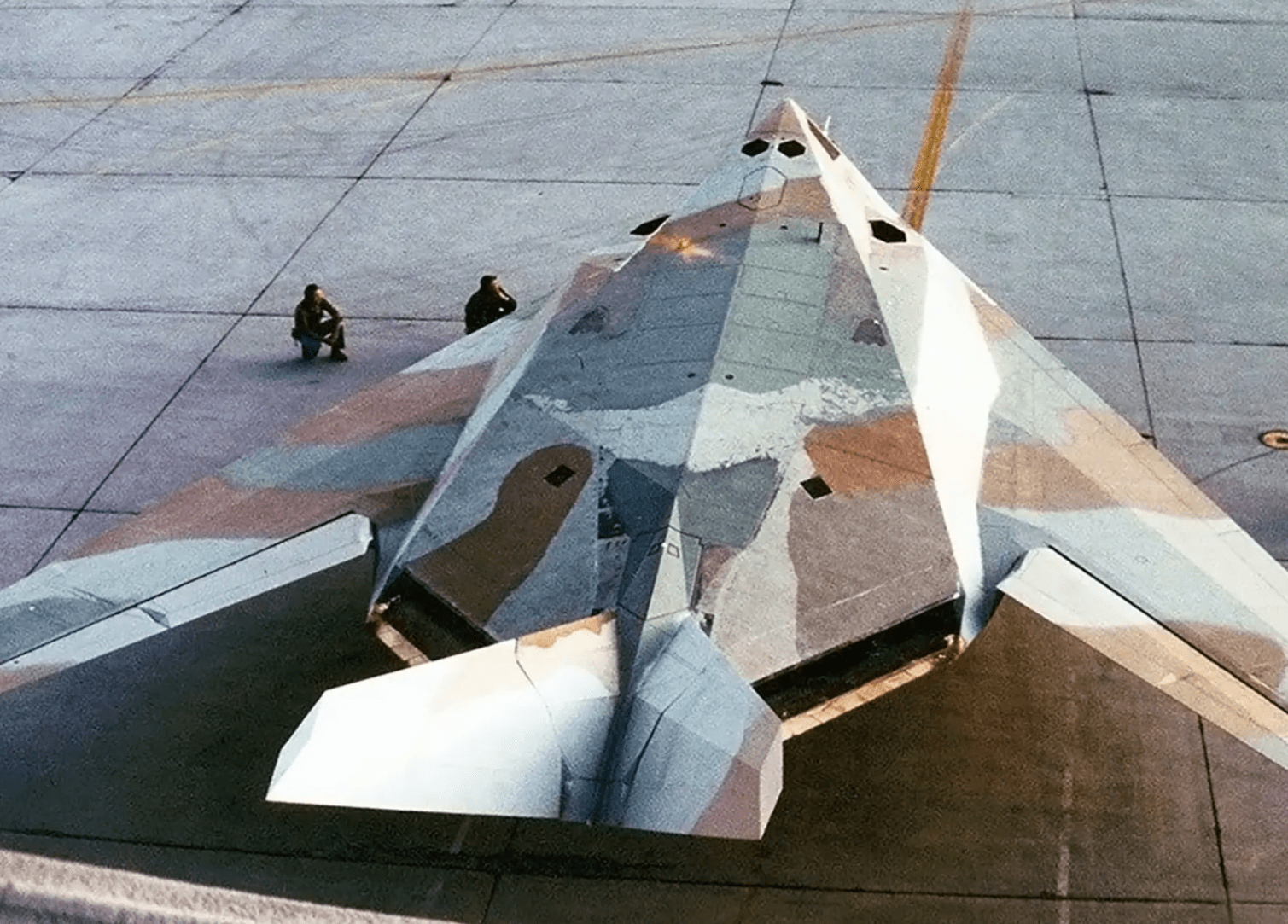

- The Nighthawk really does have a ‘stealth switch’ to go fully low observable. The switch in question gets rid of any antennas, retracting them below the skin. As of Operation Desert Storm, the F-117 drivers were flying the jet with no radio comms, alone, in the dark. By the mid-1990s, work was underway on a new generation of stealth antennas, conformal to the fuselage or wings, as found in the F-22, for example. As for the wings of the F-117, JB shows us that the angle of wing sweep — 68.5 degrees — was literally generated by engineers folding up a piece of paper like a paper dart. The final result was a jet that derived 60 to 70 percent of its stealth from the shape and the rest was provided by radar absorbent material, or RAM.

- The grid-like coverings protecting the F-117’s intakes incorporated windscreen wipers. Well, wipers of a kind, anyway. The grids, which JB compares to ice-cube trays in appearance, are designed to trap radar energy “like a Roach Motel.” But, when flying through clouds, these grids could become genuine ice-cube trays, when trapped moisture froze. “So, if you’re getting ice,” JB explains, “you hit the switch and the windshield wiper scrapes the ice off of there.” Depending on the type of ice, the pilot could also inject antifreeze into the coverings for the same effect.

- There was a crazy idea to have the F-117’s cockpit filled with carbon monoxide. Since the pilot’s head was calculated to have 200 times the radar signature of the rest of the jet, this made sense, in that the CO atmosphere would help reduce the internal radar signature. Happily, however, the pilots rejected this proposal.

- The F-117’s radar-defeating facets partly derived from the limitations of 1970s-era computer processing power. The available computer modeling system could be used to assess the stealth properties of a finite number of flat surfaces far more easily than it could a set of curved surfaces — “And that’s why the F-117 has got the flat sides.”

- Those distinctive four pitot booms poking out of the F-117’s nose, are probably the “highest tech part” of the jet, JB contends. One boom serves each of the four flight-control computers, for accuracy and redundancy. The tips of those probes are also specially faceted to measure pressure differences — this meant that the jet doesn’t need to have conventional angle-of-attack vanes or sideslip vanes sticking out from the side and into the airstream. Apparently, the tip of the dynamic pressure port is the only area anywhere on the jet that’s aligned to the direction in which the airplane’s flying.

- Among the hodgepodge of components and subsystems from other aircraft that were taken over to speed the development of the F-117 was the flight control system from the F-16. JB recounts how, when Nighthawk testers found a serious bug in that system, an anonymous individual made a call to the disbelieving F-16 program manager and requested them to ground the Viper fleet for the problem to be resolved.

- The tailhook, used for arrested recovery during emergency landings, was buried stealthily under the skin of the F-117. If required, it would fracture its way out of the belly of the jet, requiring significant maintenance work to return it to flight.

- As The War Zone has done in the past, JB also spends some time discussing the different color schemes used on the F-117, including the pastel desert camouflage and the gray scheme that was ultimately found to be the best for nocturnal flights. Another topic we have previously explored that comes up relates to the proposed air-to-air capability of the F-117, JB relating the tale of how it was once envisaged as a hunter of the Soviet A-50 Mainstay radar plane.

Now for the F-22:

- There are especially fascinating details shared about the Raptor’s speed, including the advantages of supercruise (cruising at over the speed of sound without afterburner). As well as being more fuel efficient and stealthier in terms of infrared signature, the Raptor can happily cruise at Mach 1.6 or 1.7, without afterburner, depending on the temperature at altitude. Getting faster, the F-22 is just as impressive. While level acceleration from Mach 0.9 to 1.2 at 40,000 feet takes around 45 seconds, the time from Mach 1.6 to 1.9 is less than half that. Noteworthy, too, is that in full afterburner the F-22 pumps out 150 percent power (100 percent being full dry or ‘military’ power without afterburning). At Mach 2 and 40,000 feet, an F-22 will be at about 118 percent — “So you still got plenty left at the other end to push it up.” The Raptor tops out at Mach 2.0 — according to the Air Force manual — however, JB pushed one of the jets to Mach 2.1, just to prove that this was feasible.

- Hitting Mach 2 at high altitude in an F-15 is “very uncomfortable,” according to JB, as the engines start to struggle and the controls battle with the thin atmosphere. Meanwhile, the F-22 remains as smooth “riding in a limousine [or] like flying first class in a 787.” No surprise, then, that JB “spent more time supersonic in the first month of flying the F-22 than I had in my entire career up to that point.”

- The high-performance attributes of the Raptor have been widely discussed, and JB is clearly still in awe of just what the jet can do when pushed to the limits. What’s perhaps less well-known about the F-22 is that getting it to its high-altitude perch of 60,000 feet — giving a 10,000-foot advantage over most other fighters — requires an ensemble of special g-suit and inflatable pressure vest, as well as mask and helmet modifications to ensure oxygen flow even if the canopy is jettisoned. In training, JB experienced that the powerful blast of O2 from this set-up, which was designed to ensure that oxygen got into the lungs, caused bubbles to come out of his tear ducts — seriously uncomfortable, but at least you would stay alive.

- How about this example for all-out performance? JB recalls a test out of Edwards in which he was not allowed to go supersonic below 30,000 feet. From brake release to Mach 1.7 at 60,000 feet level flight still took just three minutes and 30 seconds. On the other hand, when on the ground, the F-22 is a very different proposition: It “kind of taxis like an old lady,” and emits a series of creaks and groans.

- As to limitations, the F-22 airframe is rated between +9G to -3G. Although 9G “is not fun and hurts,” anywhere below around 10,000 feet the F-22 can, fatigue-wise, maintain 9G until it runs out of gas. The Raptor is not limited by angle of attack, however, and JB recalls seeing the F-22 happily fly at an angle of attack of 110 degrees. There is also a temperature-limiting region within the flight envelope — at the speeds and altitudes the Raptor works, the surface temperature of the jet can reach 467 degrees Fahrenheit, sufficient to cook a pizza.

- JB also provides some interesting insight into how the F-22 would be used to maximize its stealth advantage in aerial combat: “With stealth, we’re playing a little bit of a cat-and-mouse game. I know where these [radar] spikes are, and I may want to show you that I’m over here — Hey! Now, what are you doing? Turning on your radars, turning on your missiles, and the whole time you’re doing that I’m figuring out where you are. I turn a little bit. I’ve gone invisible, you can’t shoot me. And you might think I want to send a little hate your way, poke out your eyes … so it’s all a cat-and-mouse game.”

Check out the whole video for yourself below:

What parts did you find interesting? Let us know in the comments below!

Author’s note: Thanks to @MIL_STD on Twitter for bringing this video to our attention.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com