There was a time when elements of the U.S. Navy appreciated the complexity, effort, duration, and assets anti-submarine warfare, or ASW, demanded of a fleet. Expecting to fight a blue-water war-at-sea campaign against a maturing Soviet Navy, serious investment was made toward developing the best sensors and weapons that could defeat any undersea threat.

Designed in response to the existential crisis created by the speed, endurance, and performance of nuclear-powered submarines, as first demonstrated by the USS Nautilus, 63 frigates were built for service in the U.S. Navy between 1962 and 1974 across three classes: the Garcia, Brooke, and Knox.

Anticipating the need to adequately equip these ships with a variety of the most advanced sensors, weapons, and fire control systems, the Navy initially designed them with a state-of-the-art bow-mounted sonar.

Once detected by the frigate’s sonar, an enemy submarine could either be sunk or discouraged from completing its mission by anti-submarine rockets (ASROC) armed with a nuclear depth bomb or a lightweight torpedo (LWT), deck-launched LWTs, stern-launched heavyweight torpedoes (HWT), and an unmanned/manned helicopter armed with LWTs or a nuclear depth bomb.

At one point, the Navy even had the audacity to consider arming these warships with the newest HWT then being developed: the Mk 48.

It’s a cautionary tale that should be factored into anti-submarine warfare decisions being made today.

The Nautilus Scare

During initial combat effectiveness trials, the USS Nautilus (SSN-571) stunned the anti-submarine world with its sustainable speed, agility, and elusiveness while successfully attacking and re-attacking high-value targets and their escorting destroyer screens. Norman Friedman describes the attempted ASW response in his seminal work on US submarine design: “By the fall of 1957, Nautilus had been exposed to 5,000 dummy attacks in U.S. exercises. A conservative estimate would have had a conventional submarine killed 300 times; [Nautilus] was ruled killed only three times … in effect, Nautilus wiped out the ASW progress of the past decade.”

At that time, the Mk 37 HWT was the most advanced ASW torpedo used by both submarines and surface ships. Its homing, wire guidance (in the Mod 1 version), dual speed, and estimated range of 23,000 yards (11.5 nautical miles at 17 knots) established the 19-inch HWT as the best weapon against faster and hydrodynamically more efficient post-war diesel submarines, particularly when the enemy was snorkeling. However, it was clear that this torpedo’s estimated maximum speed of 26-27 knots, its total range, and its acquisition range (about 1,000 yards) were simply no match for the endurance and speed of a nuclear submarine.

In ASW exercises the Mk 37 was having great difficulty finding and then chasing down the first-generation Nautilus and the Skate class nuclear fast attack submarines. Even so, Friedman acknowledges that the “Skates actually suffered hits.” But the much faster, second-generation, teardrop-shaped Skipjack class and the almost undetectable third-generation Permit class, as well as the very slow (16 knots) but ultra-quiet USS Tullibee (SSN-597) were able to outsmart, out-dive, and/or outrun the Mk 37.

Forced to an unwanted conclusion, the practitioners of ASW acknowledged that their reliance on current sensors and weapons designed to detect, localize, and kill their underwater adversary was simply obsolete. As this devastating revelation unfolded, the U.S. Navy decided it needed an urgent replacement for its surface and sub-surface launched Mk 37 ASW HWT.

Nobska and RETORC II

The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Arleigh Burke, was not happy. In late 1955, he asked the Committee on Undersea Warfare (CUW) to hold an ASW conference the following summer to determine how to approach and defeat the nuclear submarine threat. Project Nobska met from June to September of 1956 and delivered its report to the CNO in December. As might be expected, Nobska addressed the torpedo problem.

Though fraught with diplomatic and ethical considerations, an immediate and rather drastic response was to develop and quickly deploy a nuclear depth bomb, known as the Mk 101 Lulu, and a nuclear-tipped anti-submarine torpedo, the Mk 45 ASTOR. This submarine-launched HWT had a meager range of five to eight miles and was wire-guided for command detonation, not acoustic homing.

Meanwhile, Nobska also gave birth to the Research Torpedo Configuration, or RETORC II program which was charged with designing and developing a heavyweight torpedo that could be fired from both submarines and surface ships. The primary goal set for this new torpedo was that it must run at twice the speed and range of the Mk 37. Initially known as EX-10, it would become the Mk 48 torpedo.

A Brief History of the Mk 48

Ten months after the Nobska report was delivered to the CNO, the Bureau of Ordnance began feasibility studies on the new HWT. “In the late 1950s, a series of RETORC II test vehicles were built and evaluated…” writes John Merrill in his comprehensive study of undersea warfare sensors and weapons systems. The evaluations were quite successful: “In-water tests demonstrated a reduction in self-noise, a five-fold increase in acquisition range, and torpedo speed more than doubled.”

After almost a decade of highly motivated and deeply committed development and evaluation by the Naval Underwater Systems Center (NUSC), Westinghouse was awarded the initial contract for the Mk 48 Mod 0. This was developed by the Ordnance Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University with a variable-speed turbine for its propulsion. However, it was, at the outset, exclusively designed for ASW.

Problems and cost of the Mod 0 turbine, as well as the Navy’s new desire to have the new torpedo also attack surface ships, caused delays. Because of this, Gould, Inc., and the Naval Surface Warfare Center were tasked to develop a competing torpedo designated the Mk 48 Mod 1. This torpedo would have an external, axial piston engine reducing the overall price of the weapon and it would be able to kill surface ships.

With the early-World War II Mk 14 submarine-launched torpedo debacle fresh in their minds, the NUSC embarked on an aggressive evaluation of the new torpedo. “The Mark 48 torpedo pre-introduction testing had proved to be the most extensive underwater weapon system evaluation ever conducted by the U.S. Navy,” writes Merrill, “with 227 range runs of the Mod 1 torpedo and a total of 300 runs during the evaluation of the Mod 0 and 2.”

Conducting a final ‘shootout’ before the Navy decided which version to buy, “more than 480 side-by-side firings were conducted in accordance with the Naval Sea Systems Command’s selection test plan, which included several threat scenarios… at AUTEC…”

In 1972, the Gould, Inc. Mk 48 Mod 1 was chosen. It would replace the Mk 37, which would become a mobile mine, as well as the nuclear-tipped Mk 45 ASTOR.

The new torpedo’s maximum estimated speed was 55 knots with an estimated range of 48,000 yards (24 nautical miles), an estimated acquisition range of 4,000 yards, and an estimated diving depth of over 1,000 feet. Between 1973 and 1980, the new torpedo would be fired over 13,000 times from submarines during training exercises.

Despite expected teething problems, this HWT proved itself an outstanding ASW weapon.

Arming Surface Ships with Mk 48, Part I: FRAM Sets the Precedent

Since Robert Whitehead offered his refined weapon to the world’s navies in 1868, surface warships have been attempting to sink one another with the torpedo. By the end of World War II, the increasing distances between opposing battle fleets — created by the well-armed airplane and the advent of the anti-ship cruise missile — made ship-to-ship torpedo warfare obsolete.

However, this didn’t put the weapon out of a job. The altering effect the submarine brought to naval warfare and the alarming numbers the Soviet Navy was perceived to be building during the immediate post-war years ensured that a homing torpedo fired from the decks of a surface warship would find lasting employment trying to locate and eliminate the undersea threat.

The Navy had an abundance of World War II-era destroyers that were also obsolete, but they had nothing else available in great numbers to escort aircraft carrier battle groups (CVBG) and convoys. The Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization (FRAM) program was created to extend the lives of these workhorse destroyers and update their weapons and sensors.

Ninety-five Gearing class destroyers were modified under FRAM I, which was primarily for ASW. Thirty-three Allen M. Sumner class destroyers were modified primarily for anti-air warfare (AAW) under FRAM II, although these ships would also receive ASW sensors and weapons.

One such modification to the FRAM II destroyers was a new type of 21-inch, single-tube HWT launcher: the Mk 25.

It was designed to fire the Mk 35, the first surface-launched ASW HWT produced for the US Navy. However, the new launcher was adapted to fire the Mk 37. Its placement amidships would complement the new triple-tubed Mk 32 launcher which could fire the second-generation Mk 44 LWT and eventually the third-generation Mk 46 LWT.

Of course, as we have discussed, the Mk 37 was not up to the task of killing a nuclear submarine.

Arming Surface Ships with Mk 48, Part II: Ocean Escorts

Initially designated destroyer escorts (DE) and called ‘ocean escorts,’ the Garcia, Brooke, and Knox classes were ridiculed for not being fast enough, not being well enough armed offensively or defensively, and not having enough sensors. Some even complained they didn’t look ‘fearsome’ enough. In fact, one prize-winning naval essayist wrote of one of the frigate classes: “We have wrought the DE-1052 [Knox] class, the greatest mistake in ship procurement the U.S. Navy has known.”

Of course, this gentleman had not met the Littoral Combat Ship.

At 27-28 knots maximum speed, the ocean escorts certainly were not as fast as their ASW destroyer-kin, the 30+ knot FRAMs. However, they could keep station at normal CVBG speeds. Far more important, they could shepherd convoys, amphibious battle groups, and underway replenishment (UNREP) ships with ease.

As far as sensors and weapons are concerned, all three classes were equipped with the AN/SQS-26, the bow-mounted sonar that was actively detecting unalerted submarines at ranges sometimes greater than 30 nautical miles.

For the kill, these three classes were armed with LWT tubes that could fire both the Mk 44 and Mk 46 ASW homing torpedoes. Each ship also carried an RUR-5 Anti-Submarine Rocket (ASROC) box launcher capable of delivering a W44 nuclear depth charge or LWT up to six nautical miles away.

By this time, the Navy had fully appreciated the role the manned helicopter could play in ASW, and each ship would carry the Light Airborne Multipurpose Helicopter (LAMPS) Mk 1 SH-2 Seasprite which could also carry the LWT.

But the Navy wasn’t done. Two fixed Mk 25 HWT tubes were mounted in the stern of the Garcia and Brooke classes and were planned for the Knox. More importantly, the service wisely understood that the remarkable active sonar ranges the SQS-26 was seeing demanded a deck-mounted weapon that could be launched even when the helicopter could not. They also needed an HWT that could deliver an almost certain kill to both a diesel and nuclear-powered submarine, in an ASW world that was increasingly concerned about the ability of LWTs to do the job. Clearly, the Mk 37 just wasn’t up to the task.

The obvious answer was to arm them with the Mk 48.

The Mk 48 – It’s Not Just for Submarines

The fact that the Garcia and Brooke classes were already fitted with the stern-mounted 21-inch torpedo tubes during construction meant they were ready for the introduction of the Mk 48. After all, they had already been carrying the Mk 37 HWT operationally since 1962.

In 1971, Admiral Zumwalt, the CNO, testified about the use of the Mk 48 torpedo in surface ships before the House Appropriations Committee:

“There are still provisional arrangements, in the form of space and weight reservations being made for the introduction of the Mk 48 torpedo into surface ships. Additionally, we have configured one surface escort, the USS Talbot, to fire the Mk 48, and are planning to include firing Mk 48 torpedoes from this ship in the operational evaluation of the Mk 48 weapons system. This will provide data to develop firing doctrine and will complete the groundwork for arming surface ships with the Mk 48 torpedo should this course of action be decided upon.“

Additionally, Vice Admiral Charles S. Minter fielded questions about surface escort evaluation of the Mk 48 asked of him during Senate hearings: “Approximately 50 test launchings have been conducted from deck-mounted tubes on surface craft of various types including a destroyer escort USS Bridget (DE-1024). These tests have established that the Mk 48 torpedo is suitable…”

VADM Minter also identified two other classes of ships that had space and weight reservations set aside for arming with the Mk 48: the Belknap class cruiser (initially designated a frigate), and the nuclear-powered cruiser USS Truxtun (CGN-35).

It certainly seemed that these surface ships were going to be armed with the powerful Mk 48 HWT.

The Mk 48 – Actually, It is Just for Submarines

By the time the Navy changed its designation of the ocean escorts from destroyer escort to ‘frigate’ in 1975, they were installing AN/SQS-35 variable-depth sonars into stern torpedo spaces of the Knox class and had begun removing the Mk 25 stern torpedo tubes from the Garcia and Brooke classes.

Through the years, a variety of reasons have been offered for why the Navy chose not to arm the Garcia, Brooke, Knox, and Belknap classes and the USS Truxtun with the Mk 48 and remove the Mk 25 tubes from the two oldest classes. The most cited was budgetary.

As the Cold War progressed, sonar technology confirmed that, in the right conditions, the submarine was indeed the best platform to hunt and kill another submarine. Also, the submarine’s inherent stealth and the painstaking effort the U.S. Navy had taken to make their submarines extremely quiet supported the priority of arming all of its submarines with the Mk 48 torpedo.

At $894,000 apiece (FY 1979 buy of 127 torpedoes) and amid the massive post-Vietnam War defense budget cuts, it really did make sense to prioritize the Mk 48 for the 13 boats of the Permit class, the 38 boats of the Sturgeon class, and the 41 ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) of various classes. Additionally, the first keel for the new Los Angeles class SSN was laid down the same year the torpedo became operational and in 1976, the keel was laid down for the first Trident class SSBN.

Yet, even before the Mk 48 became operational, the Navy seemed to have already made up its mind. In his 1972 testimony before the Senate, VADM Minter engaged in this exchange with a senator who asked why the necessary gear to arm the designated surface ships with the Mk 48 has not been installed:

Answer: “At present our requirement for surface ships is limited to a single ship configuration for purpose of test. Neither present nor projected funding requirements include the cost of equipping surface ships with the Mk 48 torpedo.“

Question: “If they do not, why not a full disclosure as this will be a costly program?“

Answer: “Navy plans and cost estimates are based on approved objectives which at this time do not include requirements for installation of the Mk 48 torpedo system on surface ships.“

Question: “When do you expect to begin surface ship introduction?“

Answer: “The primary reason for development and procurement of the Mk 48 torpedo system is to provide our submarine force with a weapon capable of coping with the present and future threat. As a secondary objective, it was advisable to make this weapon surface-ship compatible … in the meantime, the Mk 46 torpedo will remain as the primary ASW weapon for our surface ships.”

The arming of surface ships with the Mk 48 died a quiet death.

A New ASW Philosophy: On the Nature of Putting Your Eggs in One Basket

In the late spring of 1970, Okean 70 was recognized as “not merely the Soviet Navy’s but history’s largest peacetime naval exercise,” according to Norman Polmar’s 50-year reflection on the event. Okean, or Ocean, 70 “…included 84 surface warships, 80-some submarines (including 15 nuclear powered), and 45 naval auxiliary and intelligence-collection ships, plus several hundred aircraft.”

The Soviet Navy had finally convinced not only its own government, but also the West by providing tangible proof that it was a blue-water navy.

This exercise only added to the troubling outlook the 1970s U.S. Navy faced. The rapidly diminishing post-Vietnam War defense budget would have to be divided primarily among the Navy’s demand for the new Nimitz class aircraft carriers, the new Ohio class SSBNs, and the new Los Angeles class SSNs. Once again, the non-sexy field of ASW would be targeted for ‘necessary’ cuts.

As VADM Minter described above, the Mk 46 LWT would be relied upon to be the “primary” ASW weapon of both the surface navy and Naval Aviation (NAVAIR). Even the ‘happy time’ of the 1980s Reagan Navy would fail to produce committed research and development of additional deck-launched or air-dropped conventional weapons to supplement the LWT.

With the end of the Cold War, the lightweight torpedo would become the sole surface/air ASW weapon when the nuclear-tipped ASROC and air-dropped B57 nuclear depth bomb were taken out of service.

The ASW eggs had been moved to a single basket.

The very unwise reliance on a single weapon was not the only problem. During my time as an acoustic sensor operator in the S-3 Viking, I had heard whispers that the Mk 46 torpedo was not reliable and several of my pilots and Naval Flight Officers quietly expressed their doubts that we would be able to disable or kill an enemy submarine.

Concerns about the reliability of the LWT and its ability to defeat Soviet submarines, particularly the newest classes being built, were finding voice in 1980s naval literature.

Articles with titles such as Torpedoes: Our Wonder Weapon! (We Wonder If They’ll Work) and disturbing comments such as “The Mk 46 … Stingray [LWTs] … might have been barely adequate in the early 1960s … [they are] frighteningly unconvincing against modern, fast, deep-diving Soviet submarines” supported the whispers I was hearing.

This alarming comment was written by then CDR Roy Corlett, U.K. Royal Navy, in the 1982-83 issue of Jane’s Naval Review. CDR Corlett’s credentials included commanding a Royal Navy submarine and serving as Staff Weapons Officer to Flag Officer, Submarines.

But the most troubling event supporting the whispers was the most recent, modern war-at-sea: the Falklands conflict.

Over 200 weapons were expended against targets thought to be submarines by Royal Navy ASW forces, according to some sources. Many of these were lightweight torpedoes. In fact, from April to June 1982, helicopters dropped 24 Mk 46 and six Mk 44 LWTs, according to Mario Sciaroni’s excellent work on the Royal Navy ASW campaign. Yet, for more than a month, the Argentinian submarine ARA San Luis (S-32) was neither deterred nor destroyed. After the disabling of the ARA Santa Fe (S-21), the San Luis was the only threat submarine the British faced.

The US Navy knew it had a problem. The Mk 46 just wasn’t going to do the job. Thus, a long journey began to update and eventually replace the sole surface-ship-launched and air-dropped LWT.

The Mk 46 Mod 5 NEARTIP, or Near-Term Improvement Program, only addressed some of the problems and failed to convince the nay-sayers. Worse still, despite its impressive speed, the Mk 50 had a relatively short service life of only a decade. Apparently, its shaped-charge warhead did not perform as advertised nor did its propulsion system.

The Navy moved on to the Mk 54 which uses the Mk 46’s propulsion, a regular high-explosive warhead, and the homing software of the Mk 48. By the Navy’s own confession, this torpedo isn’t working as desired, either.

Over the years, do you know what I have also heard frequently whispered?

‘Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.’

The Business of Frigates

On March 30, 1987, the keel for the final Oliver Hazard Perry class frigate, the USS Ingraham (FFG-61), was laid down. Now, 36 years later, the U.S. Navy is going back into the business of frigates.

Traditionally, the modern frigate was designed to escort convoys, amphibious battle groups, and high-value assets such as underway replenishment (UNREP) ships through submarine-infested waters.

Under the shadow of the failed LCS program, the potential decommissioning of all Ticonderoga class cruisers by the end of the decade, and a planned 90-hull build of the Arleigh Burke class destroyer, the Navy can use as many frigates as it can get to supplement a limited ASW-capable surface fleet.

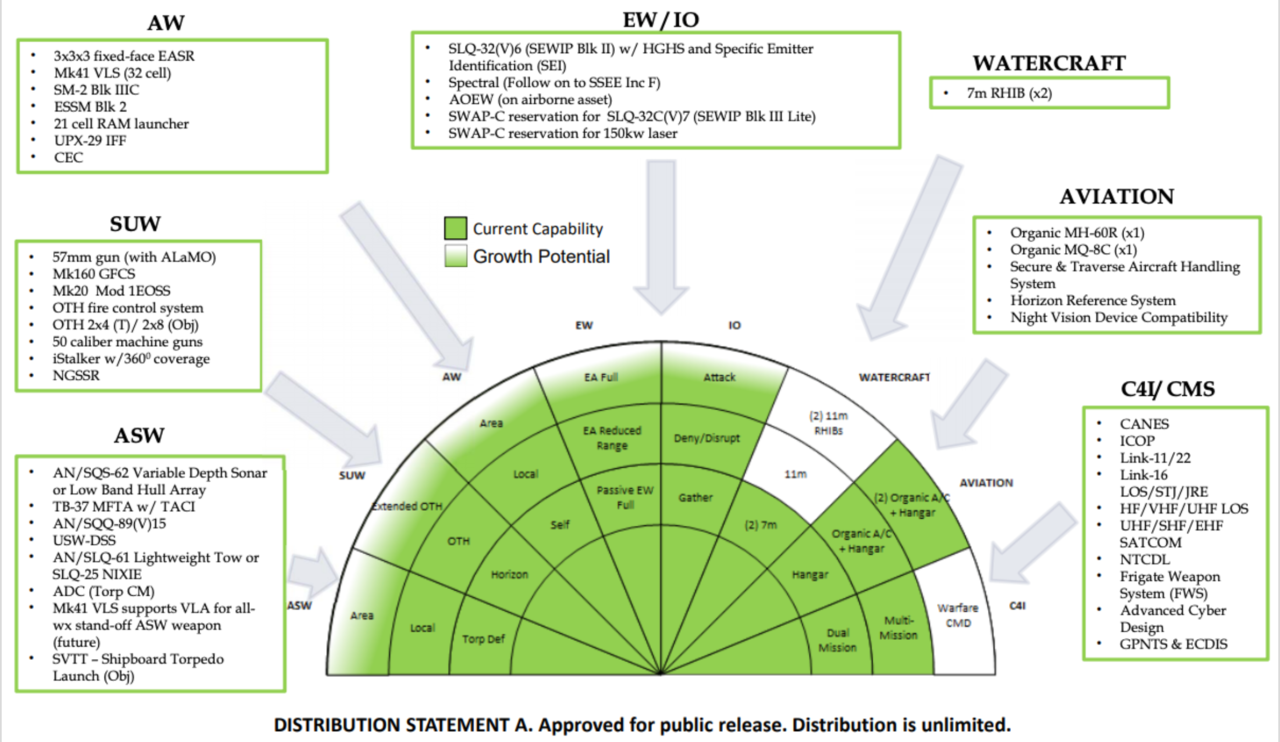

Unfortunately, the Navy is only planning on building 20 hulls of the 7,291-ton, 496-foot Constellation (FFG-62) class frigate. While the most recent report on the frigate states that new warship is multi-purpose, the project manager claims it is “primarily an ASW platform.”

For the ASW fight, the FFG-62 has the following planned sensors and weapons:

- AN/SQQ-89(V)15 Integrated Undersea Warfare (USW) Combat System Suite

- CAPTAS-4 variable-depth sonar

- TB-37 Multi-Function Towed Array (MFTA)

- Mk 41 Vertical Launch System

- Surface Vessel Torpedo Tubes (2 x Mk 32 LWT triple launcher)

- RUR-139 Vertical Launch ASROC (Mk 54 LWT)

- Mk 54 lightweight torpedo

- LAMPS Mk III helicopter (MH-60R w/Mk 54)

- MQ-8 Fire Scout Unmanned Helicopter (possibly w/Mk 54)

On paper, this seems to be an impressive list to meet the submarine threat. But lists can be deceiving and the 21st-century anti-submarine battle is proving to be unlike anything any navy has experienced.

Commitment to One-Basket-ism

“An anti-submarine warfare (ASW) campaign will be the unavoidable opening phase of conflict in the Western Pacific, one of the planet’s toughest acoustic environments. It will be a “come as you are” street fight against an adversary who may engage us in unanticipated ways. Whether this confrontation is ultimately with China, or perhaps with Russia, or any of a number of other nations with small but capable submarine forces, we are likely to get an ugly surprise.“- Vice Admiral James R. Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.) and Rear Admiral Richard F. Pittenger, USN (Ret.) in “ASW – Will We Ever Learn?”

From an ASW perspective, two things stand out about the Constellation class frigate: the conspicuous absence of a bow sonar and complete reliance on one weapon to engage a submarine: the Mk 54 lightweight torpedo.

Considering that the FFG-62 will be traversing the diverse waters of the Indo-Pacific theater when the probable next war-at-sea breaks out, not taking advantage of every available submarine-hunting sensor, such as the SQS-53C bow sonar — which is an essential element of the complete AN/SQQ-89 Integrated USW Combat System Suite — seems terribly misguided. (I will address this issue in a future article).

But then to rely solely on the Mk 54 LWT, which at the Navy’s own admission isn’t all that it should be, points to the sea service still not taking its frigate design or ASW seriously.

A 2014 report states that the LWT is “not operationally effective. During operationally challenging and realistic scenarios, the Mk 54 (BUG [block upgrade]) demonstrated below threshold performance and exhibited many of the same failure mechanisms observed during the FY2004 initial operational testing.”

Ten years and the problems weren’t fixed.

A 2016 report isn’t any better: “The new version, designated the Mk 54 Mod 1 torpedo, is scheduled to begin OT&E in FY20. The Navy started the Mk 54 Mod 1 development in FY07 and in-water developmental testing in November 2015. The Navy has completed 16 of the planned 80 Mk 54 Mod 1 developmental test firings and obtained valid test data from 11… Based on data collected in the Navy’s scaled Mk 54 warhead tests executed in FY16, it is assessed the Mk 54 will remain not effective even with the Mod 1 fixes.” (Italics, mine).

Not only am I hearing those whispers from the past about eggs and baskets, I am deafened by the screams from the ghosts of World War II about unreliable torpedoes.

The Audacity of Growth

In the latest report to Congress on the Constellation class frigate, the “growth margin” is discussed:

“Another potential aspect of this issue is whether the Navy more generally has chosen the appropriate amount of growth margin to incorporate into the FFG-62 design. The Navy wants the FFG-62 design to have a growth margin (also called service life allowance) of 5%, meaning an ability to accommodate upgrades and other changes that might be made to the ship’s design over the course of its service life that could require up to 5% more space, weight, electrical power, or equipment cooling capacity… Skeptics might argue that a larger growth margin (such as 10% — a figure used in designing cruisers and destroyers) would provide more of a hedge against the possibility of greater-than anticipated improvements in the capabilities of potential adversaries such as China…”

It isn’t too late to use some of that growth margin now and consider adding one Mk 48 Mod 7 Common Broadband Advanced Sonar System (CBASS) tube to the stern of the FFG-62. Of course, because of the Mk 48’s remarkable range, the SQS-53C bow sonar must be added to the frigate design as well.

If not already, production of new Mk 48s in large numbers should be one of the highest priorities of the U.S Navy.

Keep in mind, the Constellation class frigate is 3,000 tons heavier, almost 60 feet longer and almost 20 feet wider at the beam than the Knox class frigate which originally had two HWT tubes planned for its stern. The stern of the FFG-62 can be modified to accommodate both a VDS and a single Mk 48 torpedo tube with reloads.

A single HWT tube might be risky, but dependency on a single ASW weapon with a questionable history and reliability is a risk that shouldn’t be taken.

Along with frigates, it’s time for the U.S. Navy to get back into the business of being audacious.

Author’s note: I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Susan Brook at the US Naval Institute for providing a digital original and giving permission to use the remarkable photo of the USS Talbot firing the Mk 48. Also, I am grateful for the permission to use the Mk 25 HWT tube mount photo and assistance from Ron Babuka, former crewman of the USS Allen M. Sumner (DD-692) and editor of the website dd-692.com

Kevin Noonan served in the U.S. Navy from 1984–94 as a sensor operator (SENSO), briefly, in the P-3B Orion with VP-94 and for the remainder of his service as a SENSO in the S-3A/B with VS-41, VS-24, and VS-27.

Contact the editor: oliver@thewarzone.com