In my previous article, I described two intense days frantically hunting a Soviet submarine in the Strait of Gibraltar back in 1967. I was a low-ranking sailor serving aboard the USS Steinaker — the World War II-era Gearing class destroyer I sailed on for two years. Now I’d like to describe some of our other high-seas adventures, and what life was like living aboard a destroyer in those days.

Like A Living, Breathing Thing

A warship like Steinaker is never left unattended, or completely powered down. Walking around the ship, you would always be aware of machinery noises, and powerful exhaust fans venting hot air from deep in the ship’s engineering spaces. You could always feel small vibrations, as if the ship was alive, and in a way it was. The ship was powered by high-pressure superheated steam produced by two large boilers that were heated with a thick, foul-smelling type of oil called bunker fuel.

The boilers were housed in their own space. When I was a new crewman, I got a tour of the boiler room. I remember a crewman leaning over near a steam line and lighting his cigarette by touching it to the line. The heat was intense in that compartment — in some areas up to 150 degrees. The inlet end of the exhaust fans was in the boiler room, and you could stand under them to try to cool off. The steam was piped to the engine room, where it turned two turbines and probably other equipment such as generators. It would then be returned to the boiler room to be reheated.

What we usually think of as steam is really water vapor suspended in steam. Steam is a dry colorless gas. When you heat water to the boiling point, it changes state from a liquid to a gas, and you produce steam, but it doesn’t contain much energy. If you lower the temperature even slightly, it will change states from a dry gas back to a liquid again. To make the steam useful, the energy needs to be greatly increased by raising the temperature and pressure. That way it can release tremendous energy while turning the turbine and still remain a dry gas.

The ship produced 60,000 horsepower from two steam lines that were about six inches in diameter. It’s hard to wrap your mind around the power of high-pressure superheated steam. You can’t see steam. That makes a leak extremely dangerous. A leak would create a huge white cloud of vapor in the compartment, but the actual steam leak could be many feet away because the white cloud would only form once the steam had cooled and the water began changing state from a gas to microscopic liquid droplets.

When looking for a steam leak, the boiler room folks were taught to wave a broom in front of them as they slowly approached a possible source. When they waved the broom in front of the leak it would cut all the bristles off, leaving a stump at the end of the pole.

Nowadays, U.S. Navy destroyers are powered by large gas-turbine engines — just like the engines you might see on a large passenger jet but designed to turn a shaft instead of producing thrust. Gas turbines take up much less space, and the ship should be able to get underway from a cold start faster than a ship that had to fire up its boilers and slowly produce steam. The cost of running a gas turbine-powered ship must be impressive. Bunker fuel is cheap, but jet fuel is not.

Clearly, in the last five decades, just about everything on a destroyer has changed — propulsion, weapon systems, sensors, navigation, and communications. But some things have not. The mission to project power and protect the sea lanes remains the same, and destroyers are still making cruises to the same destinations we did.

The ocean remains the same, and the Navy is still faced with the same design issue — how do you cram a lot of sailors into a relatively small ship?

Challenging Living Conditions

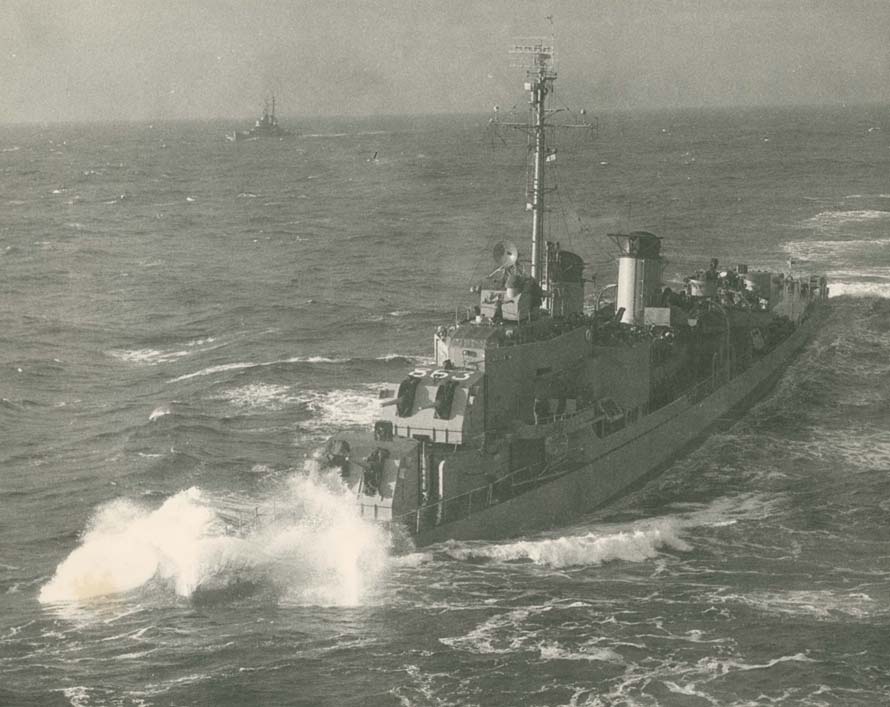

In the picture above, Steinaker is sailing at a moderate speed through calm seas. I spent half of my two years on Steinaker living in the forward berthing compartment, which was located about where you see “863” painted on the bow. In heavy weather, the bow constantly rose up (as in the photo) and then plunged into the next wave and was often completely submerged. Tons of water rolled across the deck, slamming into that forward gun mount, and was blasted high into the air where it landed on top of the 03-level where the bridge and Combat Information Center (CIC) were located.

More about that later…

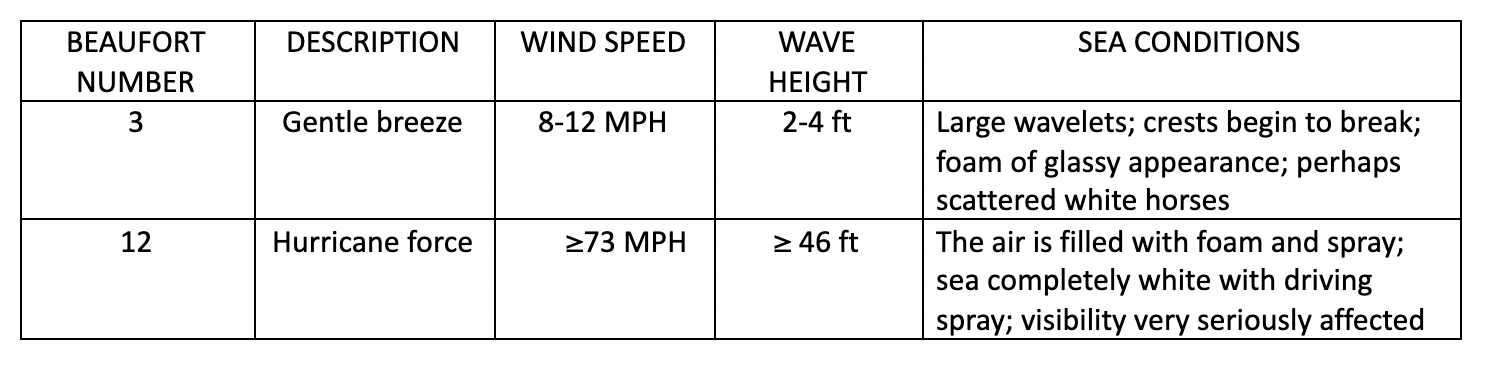

Sea states are described using the Beaufort Scale, which runs from zero to 12. In the picture, I would say this was maybe three on the scale, and that’s probably a stretch. Here are the descriptions of sea states three and twelve, for comparison:

My point is that destroyers can be rough-riding ships, even in calm conditions, but why do I mention sea state 12? Because Steinaker went through a hurricane while I was aboard. Ships do not normally steam into the middle of a hurricane, but hurricane paths are difficult to predict, and Steinaker wasn’t the first ship to relocate to avoid a hurricane only to have the storm change course and run it down.

In our case, I remember being tied up at a small pier in Key West when we got the word that a hurricane was building in intensity and heading right for us. Ships do not want to get caught in shallow or restricted water when a big storm is headed their way, so we departed to the east to get some sea room, only to have the storm unexpectedly veer to the east and run us over.

I remember the anemometer in Combat (the Combat Information Center, or CIC) hovering around 75 knots and occasionally peaking at around 100 knots. I honestly do not remember it being that big a deal. Of course, that was over 50 years ago, and I am reminded of the definition of “the good old days” — a good imagination and a bad memory. Maybe I was terrified while trapped in a windowless compartment listening to tons of water landing on top of us and hanging on for dear life.

All the chairs in CIC had seatbelts for a reason!

We had a public address system on the ship called the 1MC. I just Googled it and found that “MC” is short for “Main Circuit.” Anyway, it was common to hear, “Now hear this. All hands stand clear of the weather decks while maneuvering at high speed through heavy seas.” I took this picture with my little Minox camera showing why you would want to heed that warning:

This picture was typical of what I remember — the sea was always a dull gray and so was the sky. The only time in the two years I saw blue water was on a short trip to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. The water in the bay was beautiful and the bottom was white sand — that visit is for another time. …

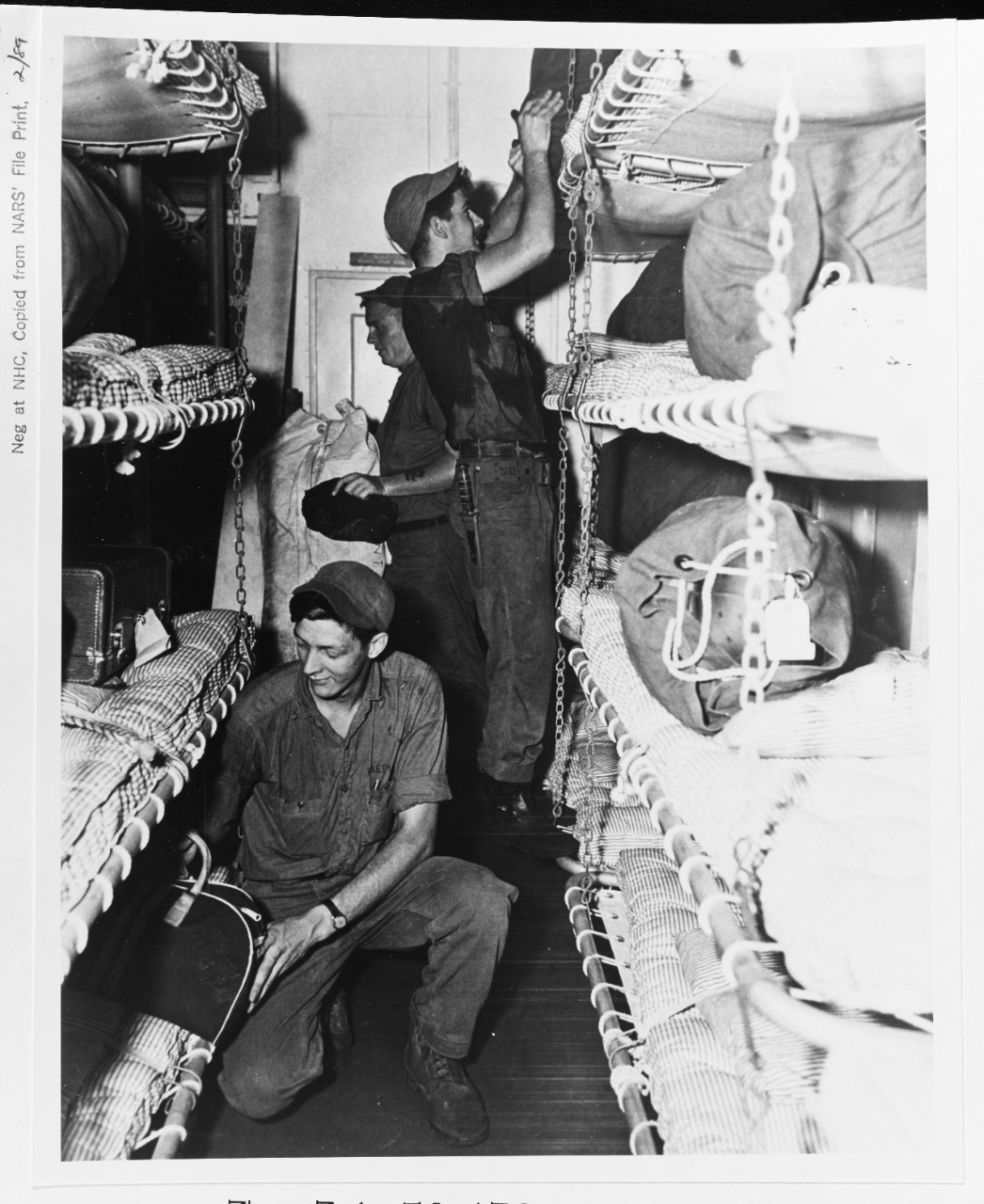

There were 21 of us housed in the forward berthing compartment, which was the size of the average apartment’s living room. Each person had a rack that consisted of a tubular aluminum frame with a canvas sheet stretched tight inside it. On top of the canvas was a thin mattress enclosed in a “fart sack,” which was like a large pillowcase.

Racks were stacked three high and lined up in rows. Some rows were freestanding, and others were attached to the bulkheads. I was in the middle between the lower and upper racks. That was a plus, as I was less likely to break my neck when I was tossed out of my rack and landed on the deck during a storm.

My row of racks was attached to the bulkhead with hinges, and the outer side was held in place with a chain at each end. When I lay flat on my back, with my elbows at my side, I could touch the top guy’s mattress with my fingers.

Between me and the bulkhead was a high-pressure steam line that ran from the boiler room to the engine room. It was insulated with asbestos and was about six inches in diameter. At my feet was a small fan. At night, when I managed to get to sleep, I occasionally stretched and stuck my toe into the fan.

Below the bottom racks were small lockers where we stored all our possessions. If that bottom rack was occupied you could not get to your locker. That often happened since we were not all in the same watch sections — half were on watch while the other half slept. So, by necessity, you might go on watch, leaving your small “douche kit” or a paperback book laying on your rack. Our chief would make regular visits into our compartment and collect any loose items he could find and lock them away in a locker he had commandeered. Each week there was a reckoning, and we were given two hours of extra duty for each item he collected.

We soon caught on to the chief’s schedule — the reckoning always took place on Friday, so each Thursday we simply pounded the hinge pin out of his locker, redistributed his confiscated items, and then replaced the hinge pin. The chief was no fool. He soon figured out our scheme and added a second padlock. He insisted that the compartment lights always be on during daylight hours, and no towels or other items could be hung from the racks above to block the light. He was beloved by all, and we all enjoyed his petty torments. Eventually, it came to the attention of the officers that some of us seemed to have a bad attitude, but I digress …

Picture yourself totally exhausted from long hours on watch and trying desperately to get some sleep. In heavy weather the bow moved up and down about 15 feet as the ship plowed through the waves. One second you were pressed down in your rack as the bow rose up the side of a wave, and the next you were floating weightless as the bow dropped into a trough. The only way to not get tossed out of your rack and onto the deck was to sleep on your stomach and wrap your arms and legs around the rack’s frame like a spider.

Each rack had some straps that you could use to tie yourself in with, but no one seemed to like those. You could also get a shipmate to tip your rack way up and shorten the chains, so you were wedged in, but then you could not get out by yourself, and that could be a big problem.

To these many layers of misery, you need to add the constant sound of the entire compartment going underwater and the noise of the sonar, which was not far below us. Actually, after a while I found the sonar restful. About once every five seconds, it made the sound you hear in every submarine war movie you’ve ever seen. Because my rack was against the bulkhead, I could hear the sonar pulse and the echoes reverberating.

At some point in my two years, I was also assigned to live in the aft berthing compartment. That was infinitely better, with no constant up and down motion, and at the far end of the ship from the sonar dome.

A Huge Storm

So far, I’ve just been bitching about normal everyday physical misery and discomfort. Now I want to talk about a storm! You may be asking yourself, what is he going to whine about now? I’m sure destroyers are completely safe in all weather conditions, right?

WRONG!

For example, on Dec. 18, 1944, Task Force 38 was struck by Typhoon Cobra — sometimes called “Halsey’s Typhoon” — off the Philippines. The destroyers USS Hull (DD-350), Spence (DD-512), and Monaghan (DD-354) all capsized and sank. Seven hundred ninety men were killed and 80 injured.

A destroyer can only roll so far before it capsizes. I think we came awfully close in the story I am going to tell you now.

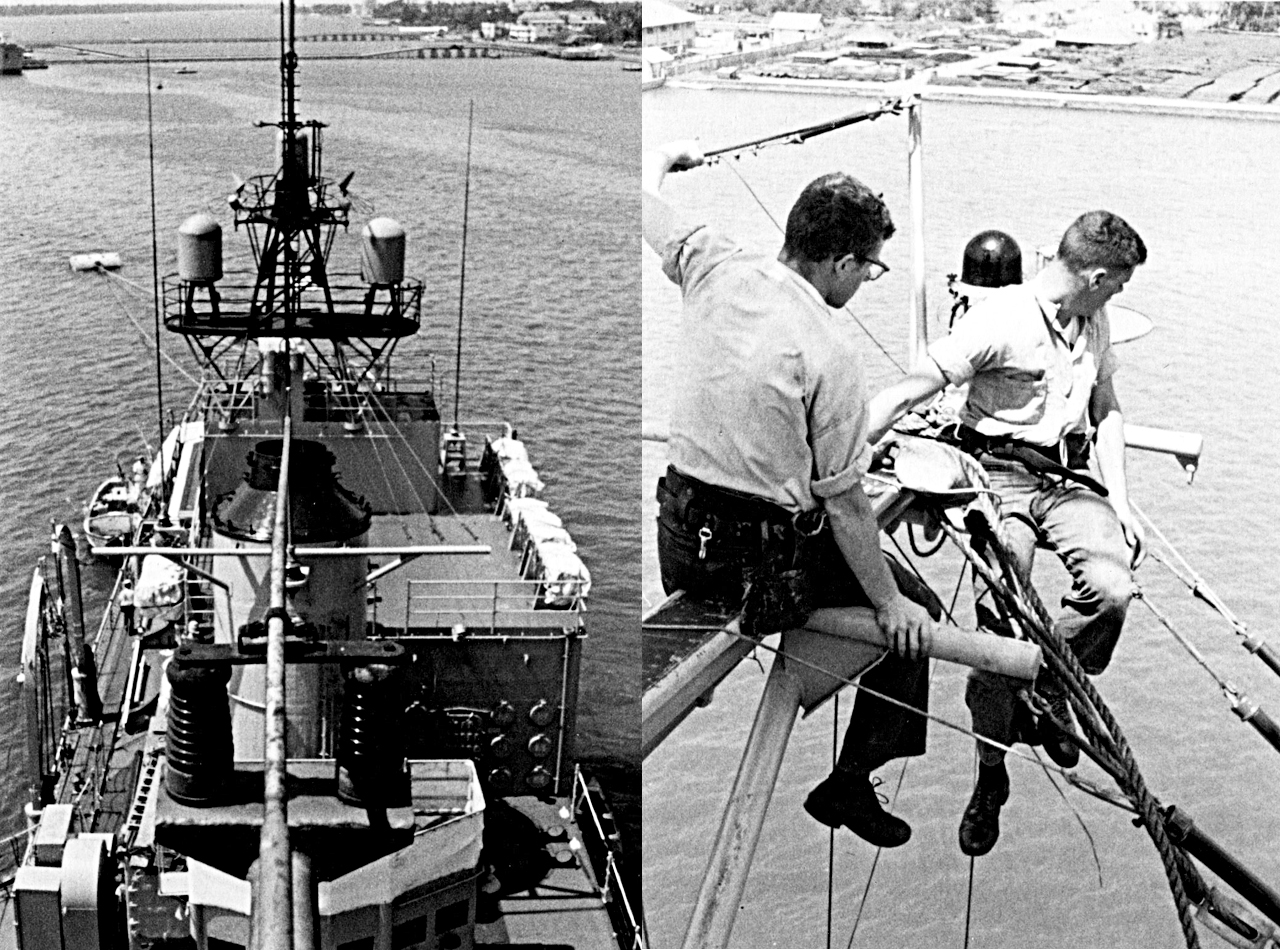

During my first Med cruise, we found ourselves tied up next to this magnificent cruise ship — the Michelangelo. I took this picture while we were both pierside in Genoa, Italy. That day, I had occasion to climb to the surface-search radar platform on the main mast with a shipmate to do some maintenance. I remember looking across at Michelangelo and commenting that it was so huge its main deck was higher than we were!

On the seventh of April 1966, we both sailed out of Genoa and headed for the Atlantic. Steinaker was heading home. Five days later, on the morning of April 12, we both found ourselves mid-Atlantic and caught in a monstrous storm. The waves were massive — the size of large buildings. Steinaker had 60,000 shaft horsepower, twin screws, and twin rudders. Normally that would result in a very capable and maneuverable ship. But on that day we were completely helpless. One minute we would be pointed north, the next east – totally out of control. The extremely odd thing was that there was no wind to speak of and the sky was blue.

Whatever had caused these massive waves was gone.

When we were at the top of a wave, we could see for several miles. There was a large merchant ship about one mile away. I remember seeing it with the bow buried in a wave and the bronze propeller completely out of the water, turning slowly and with the sun glinting off the blades. Then we would slide down into a trough and lose sight of the ship. The next time we rose, that ship would be pointed in a completely different direction. We were both in big trouble.

Above our bridge windows at the center, there was an inclinometer, which consisted of a curved glass tube filled with an amber liquid. Inside the tube was a black marble that was free to roll to the lowest point in the tube. The inclinometer was marked off in degrees. While sliding down a wave sideways, we took a starboard roll of 56 degrees. We had been told we would capsize somewhere around 65 degrees. Time seemed to freeze. Would we right ourselves or capsize? I can still see the little bubbles in the inclinometer tube in my head.

With a 56-degree roll, it is easier to walk on the bulkhead than on the deck. These extreme rolls caused everything to go flying in every direction. I ended up on my butt, jammed up against the starboard bridge-wing door at the lowest spot formed by the sloping deck and starboard bulkhead, a pile of loose items in my lap. I remember straining my neck to look out the bridge-wing window. All I could see was a massive, malevolent wall of gray water that stretched up and out of sight above us. We never practiced abandoning ship, and I don’t remember ever seeing a life jacket. We had a few lifeboats that had to be lowered by pulleys. Totally useless in rough seas.

It was clear we would all go down with the ship, or we would all make it out alive. It was just a question of physics.

Meanwhile, on the Michelangelo, a huge wave came across the main deck and crushed a large section of the ship. Four passengers were killed, and 50 were injured. Damage was extensive. The ship managed to limp into New York Harbor. Michelangelo estimated the wave height at 18 meters, or 60 feet. Sebastian Junger described this storm in his book The Perfect Storm.

Fine Dining, Destroyer Style

Food on Steinaker was … different from my mother’s cooking. Sometimes the cooks would get bored and use food coloring to dye our scrambled eggs bright green. They also had a habit of serving really greasy slimy food when the weather was unusually rough. This leads seamlessly into another topic — sea sickness. But first, a bit more reminiscing.

I do remember with great fondness the mashed potatoes. The potatoes were stored on the main deck in large cabinets with many holes for air circulation. In rough weather, they would get drenched with seawater, but the potatoes didn’t seem to mind. Mashed potatoes were universally good. I don’t think the cooks bothered to peel them, so there were small pieces of peel mixed in. I have to say that my favorite dinner ingredient was those mashed potatoes.

In my previous article about the encounter with the Russian Foxtrot submarine, I described two very intense days, but there were also times when we were simply steaming independently through the night. During times like that, things were very relaxed. Most of the crew would be sleeping, and my world would consist of the three lookouts, the bridge talker, and whoever was in Combat with me. We were all on the same sound-powered voice circuit. I remember killing time by asking everyone a brain teaser, such as “I have ten coins in my pocket. They add up to sixty-four cents. What are they?”

I’d also try to keep the lookouts company, since I’d been one earlier in my short career. If there was a surface contact on the radar I thought was visible, I’d give the lookout facing that way the bearing. The visible horizon from their height above the sea was about 13 miles to the top of another ship’s masthead lights. If you had very good eyesight, you could catch momentary glimpses of them. Anyway, occasionally, around three in the morning, the smell of baking bread would manage to work its way all the way to the top deck on the ship. One of us would go down and get a hot loaf of bread from the cook, along with a brick of butter and a jar of jam.

Man, that hot bread tasted good! I look back on rare times like that with fondness.

In general, food — especially perishable items — is loaded at the last minute before a trip. As a low-ranking crewman, I got tagged for all the working parties, and loading provisions was a common one. I remember bringing a large box of frozen beef on board. On the box it said, “USDA Good.” I’m not sure you can find that grade at the supermarket. It must be a special-order item.

Milk deserves a special category all to itself. I think the Navy tried hard to always get the very freshest milk delivered to the ship at the very last minute. Once underway, one of two possibilities would happen — either we would run out, or the milk would start to go bad. In the latter case, the cooks would attempt to forestall the inevitable by using a series of clever steps. At first adding a bit of canned milk might disguise the taste and slightly brown color. Eventually, that would no longer pass the gag test, and they would have to add sugar, and maybe some powdered milk. Finally, it became a lost cause.

Once the milk ran out, other substitutes were called for. We used to have those small cereal packs that had ten choices in a carton. For the Navy, they were packed for ocean shipment by covering them in some sort of tar paper and then vacuum-sealing them in aluminum foil. We must have gotten a batch that had been in storage since the Korean War, because the tar paper taste had permeated into the corn flakes. One morning, I remember eating a bowl of tar-flavored corn flakes with purple Kool Aid instead of milk.

Normally, the new watch section can go to the front of the chow line, eat, and then get up to CIC to relieve the watchstanders, who then have to rush down to get whatever is left. I remember arriving one day at the back of the chow line with a serious hunger. The evening meal was supposed to be chicken stew. When I arrived in front of the stew pot, I glanced inside. It looked like dirty dishwater with a few small flakes of meat floating in it. But at the bottom I could see a big juicy piece of meat. I told the cook I wanted that piece. An argument ensued, in which he wanted to know why I should get special treatment. I insisted and eventually he relented and granted my request.

I soon joined my shipmates and began attempting to cut my big juicy piece of meat. I remember that my knife was serrated, and it seemed to be scraping off crumbs. I tried reorienting the knife to cut the meat with the grain, but it didn’t seem to have any grain. Eventually, I turned it over, and it had printing on it.

I was trying to eat part of the cardboard box the chicken came in.

The largest compartment on the ship was where we ate, and it sat directly over the midship berthing compartment. There were long tables that ran across the compartment from side to side. Food was served on metal trays like school kids probably use. The table edges were lined with a small lip to help keep the trays from sliding off in rough weather. That happened so frequently that we had a name for it — Chow Course.

One particular evening, spaghetti was the main course, and I was hungry. I piled my tray high and then found a spot to sit at the end of a table. I sat my tray down, judged that the ship was fairly steady, and headed over to the bug juice dispenser. Just as I was headed back to my spot, the ship took a sickening roll that angled the table in a downward direction from my end. The tray started sliding — slowly at first. As it picked up speed, each person simply raised their tray off the table to let it pass. By the time it reached the other end of the table, it was moving! It hit that little lip like a ski jump, and it was catapulted into the air. As if in slow motion, it floated through the air without losing a single noodle and dropped straight down the hatch leading to the midship berthing compartment. Time stood still. … Imagine the boatswain’s mate’s surprise when a fully laden tray of spaghetti descended straight down that hatch and landed squarely on his head!

That wasn’t the only unexpected roll, and, in short order, people were slipping and sliding all over the place. Noodles and spaghetti covered the deck. It started to look like a tag-team mud-wrestling contest with noodles instead of mud.

Just another navy day at sea on a destroyer.

Seasickness

How’s this for a segue? When I first arrived on the ship, they were already preparing for my first Med cruise. One of the more common modes of entertainment on any ship is to mess with the new arrivals. I was almost immediately sent looking for a pot of “relative-bearing grease.”

I had been learning to fly before I joined the Navy, and I knew what a relative bearing was, so they switched to plan B: Speak constantly about how rough the ocean would be once we got underway. The goal was to get into the new guy’s head and get him worrying. Once you achieved that, nature would do the rest.

I didn’t fall for that one either. I had experience. When I was a kid, my parents moved us to New York for a few years and I had ridden the Staten Island Ferry several times. I never got seasick.

I was confident.

The waterway leading from the Norfolk Naval Base to the Atlantic Ocean is long and complicated. This whole complex collection of waterways is called Hampton Roads. It takes quite a while to reach the ocean. Once underway, I spent the time convincing myself that the ship wasn’t any different than the Staten Island ferry boat. Eventually, we reached the ocean, and I realized I was in big trouble.

It wasn’t long before I was leaning over the side and praying to the god of seasick sailors, O’Roark. That was the only time I lost my lunch, but I spent most of the remaining two years with a headache.

There is a reason for that. Fear of the unknown and lack of experience are huge problems, but easily overcome. Once you’ve been through rough weather a few times, you will know what to expect.

You can also take precautions. We used to eat an entire box of saltine crackers before heading out after being in port for a while. The theory was that having a big wad of cracker dough in your stomach instead of your stomach contents sloshing around with normal food would help.

This next story takes place somewhere in the middle of the ocean at night in rough weather. It makes no difference where it happened, and I tell it not to show that I had a cast-iron stomach or was tougher than everyone else, but to prove there is a very strong mind-over-matter aspect to seasickness.

It was a miserable night. The ship’s motion was nauseating in the extreme. There is a best course to sail for the smoothest ride, but that may not be the direction you need to go. As seems to be the case in my stories, I was on the surface-search radar and responsible for preventing collisions with other ships. I don’t remember, but if we were operating with a carrier task force there would have been a lot going on. Everything conspired to make us all want to die. Water was probably being thrown on top of our compartment, the wind was probably howling, and the smell of vomit was strong. Everyone in CIC was sick but me. That included our division officer, who was lying face down on the deck with his head near the entrance to CIC. Anyone entering would bang the door into his head. He lay near a trash can, and every now and then he would raise his head to puke into the can. I had a splitting headache, but I wasn’t incapacitated for the simple reason that I couldn’t afford to be. The safety of the ship depended on me.

If someone else had been on that position they would not have had the luxury to be sick either.

Mind over matter.

More Random Memories…

When we were in a foreign port, the crew would be allowed to go ashore after they had completed their duties for the day, but we all had to return by midnight. The age of the average junior enlisted man was probably about 20, and most had never been away from home prior to joining the Navy. Their favorite activity seemed to be to find the closest bar and proceed to get as drunk as possible.

Some thought starting a large bar fight only added to the fun. I didn’t drink, but wandering the dock area of a strange foreign port alone in the middle of the night was a bad idea. There were a lot of people that didn’t like American sailors. So, often, I would end up in a bar anyway. I could act as the designated sober guy for some of my shipmates.

In addition to the small individual lockers we each had, there was a communal locker where we kept our large pea coats. Each was kept in a plastic bag with a zipper. I bring this up because, after waking one morning, after we had all been ashore the night before, I mentioned that I had had a vivid dream. I dreamt that someone had taken a piss in the pea coat locker. It was such a vivid dream that I felt compelled to look.

I guess it wasn’t a dream after all.

The bottom of one bag was swollen with what looked like a gallon of urine. The bottom of the pea coat was immersed and it acted as a wick, so the entire bottom of the coat was saturated.

No problem. It wasn’t my bag!

One more sea story. This one also takes place in our berthing compartment. The aisle between rows of racks was narrow. On the top rack of one row lived a sailor with a temper. Adjacent to him was a sailor who snored loudly. I dreamt that they were having a fight in the middle of the night. In the morning, the sailor who snored was complaining he had been attacked by bed bugs during the night because his face was covered with welts. I glanced across to the grouchy guy’s rack and there was a metal clothes hanger that was bent up like a pretzel.

I was the only one who knew what had happened while they both slept. I kept it to myself.

Okay … One more sea story. At some point, a first-class electronics tech came aboard. A first class is a pretty high enlisted rank — an E-6. It takes years to attain that rank, but he had served his entire Navy career up to that point working ashore. This was to be his first experience on a ship. He was a genuinely nice guy and wanted to get off on the right foot with the rest of the crew, so he asked if there was anything he could do.

Big mistake!

One of the first things you learn is to never volunteer, unless you are extremely bored and want to roll the dice. Anyway, it was suggested that he could stand mail-buoy watch on the bow, which would be most appreciated. Of course, never having served aboard a ship, he was unfamiliar with how we received our mail at sea. It was explained that the Navy always knew where we were, and our intended course, so they could pack our mail in a waterproof sack attached to a bright red buoy with a flashing light attached and chuck it out of a plane directly in our path. That was such a masterful load of BS that I almost believed it myself!

Standing on the bow, searching for the mail buoy, you are visible to everyone on the bridge. No one stands on the bow underway because it’s cold and windy, and you’re going to get blasted with spray, even on a good day.

I think he lasted at least one hour.

That might have been a record!

Second Cruise Into The Med And Then To The Gulf

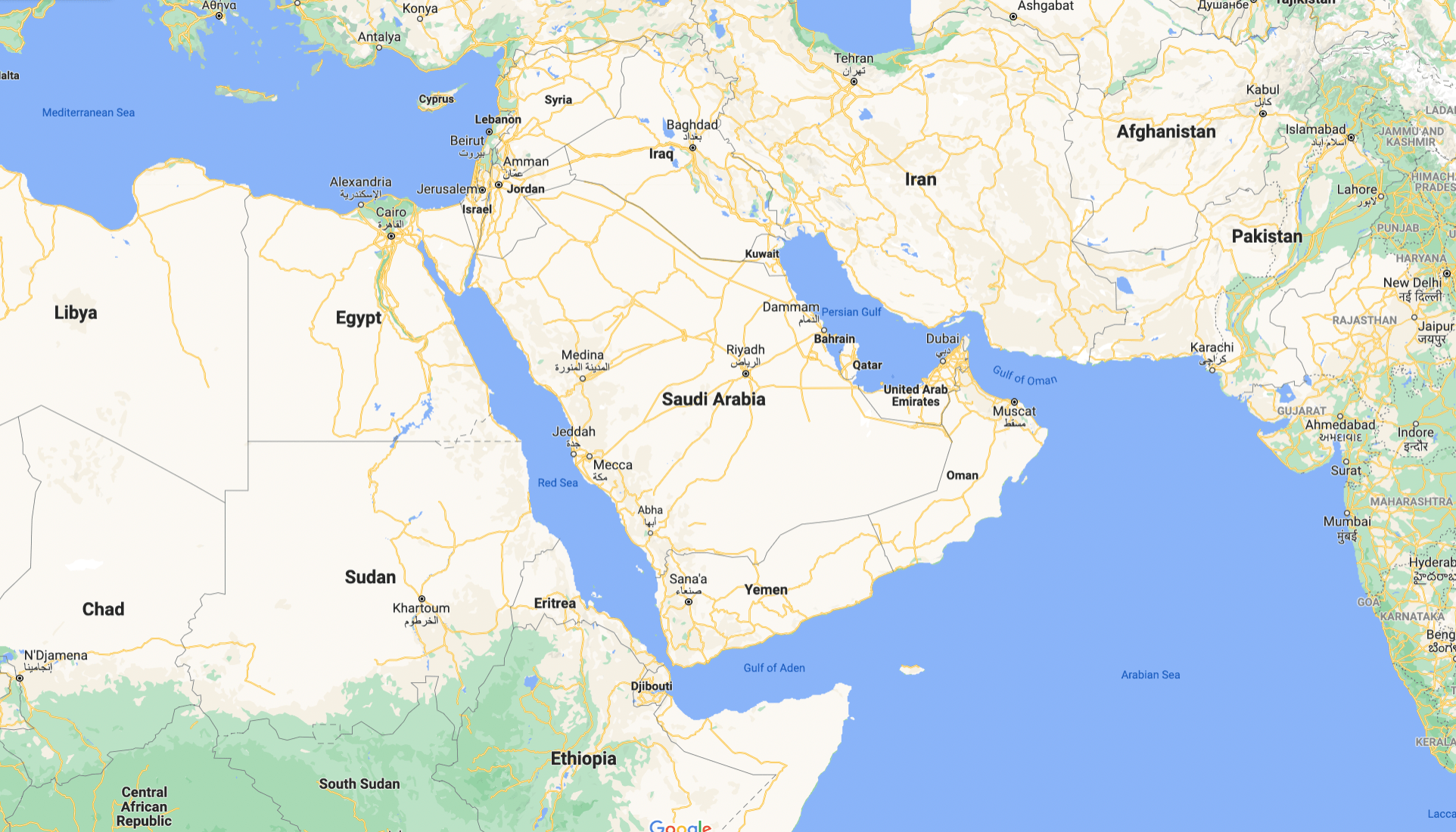

My aforementioned run-in with a Russian Foxtrot submarine occurred as we were heading for the Mediterranean Sea via the Strait of Gibraltar. Once in the Med, we made several port calls — probably Italy, France, Greece, and Spain. Then we headed through the Suez Canal to the Red Sea and into the Indian Ocean. If you’ve never been in that part of the world in summer, you do not know the meaning of the word “hot.”

The ship had a seawater intake near its bottom, where water could be drawn in to feed the evaporators to make fresh water. I think it was probably about ten feet below the surface. I remember being told that the seawater injection temperature was 96 degrees. Fortunately, during a fleet rehabilitation and modernization upgrade, the ship’s berthing compartments, critical machinery spaces, and CIC had been air-conditioned.

One of the favorite dispensers in the mess area was a soft-serve machine that produced a frozen vanilla concoction resembling ice cream. The prepackaged mix came in a five-gallon bladder inside a cardboard box. It had to be kept refrigerated. As the saying goes, bread tends to land buttered side down, so of course the refrigerator failed, and those soft-serve bladders began to ferment. As the mix began to putrefy, gas was created, and the plastic bags began to expand and break through the cardboard boxes. It was only a matter of time before those bags exploded, showering the area with unimaginable putrefaction.

So, as a junior enlisted man, I was among the lucky sailors tasked with jettisoning the bags overboard. The path from the refrigerator, or “reefer,” involved scaling a vertical ladder to the main deck. There was no way for two sailors to share the load, so we each had to shoulder a bulbous sloshing 50-pound bag and attempt to scale the ladder with one hand on the bag and the other on the ladder.

One of two things usually happened: Either the sailor lost control of the bag and it fell to the deck where it exploded, showering the area, or, worse yet, the bag burst near the head of the unfortunate sailor hanging by one hand halfway up the ladder.

Even using a thesaurus, I can’t find words to describe the stench. The phrase “gag a maggot” comes to mind.

Operating In The Gulf

Fifty-three years ago, we were the only U.S. naval vessel in the entire Persian Gulf. Currently, I believe there are oftentimes two complete carrier task forces in the area. In terms of manpower, the Navy has gone from a few hundred sailors in the region to many thousands.

A naval vessel is unique. There is a diplomatic component to any foreign port visit. Often, the captain would welcome foreign dignitaries aboard and host them for tea in the wardroom, while we were busy in the electronic countermeasures room collecting all their military radar signatures. The information collected would be sent to the nearest electronic intelligence (ELINT) center for analysis. The data collected helped determine a potential adversary’s order of battle. This may seem cynical, but history has shown that it is necessary. Charles de Gaulle is credited with the observation that nations have no friends, only interests.

After transiting the Suez Canal, we headed south in the Red Sea toward our first scheduled port visit in Yanbu, Saudi Arabia. When we arrived at the entrance to the port, we were navigating using a British Admiralty chart that had been last updated in the late 1800s. The bottom was shallow and did not match the chart, so the captain turned us around, and we left, leaving the local poobah standing pier-side with his entourage and wondering what just happened. It turned out that a lot of diplomatic effort had gone into organizing that little get-together, and the State Department was not happy.

Next, we stopped to refuel in Yemen, in the Port of Aden, where the USS Cole was attacked in 2000. It was considered a dangerous port even in 1967, and it was the first time we posted armed sentries. Once we had refueled, we turned east toward the Arabian Sea and our next port call.

Salalah In Oman

If you look at a map showing the extent of the British Empire in the early 1900s, it resembles a map of the world. They seemed to be everywhere, including the Persian Gulf.

In 1967 the Brits were still active in the region and had small bases all along the southern Arabian Peninsula. Our next stop was Salalah, a small speck on the chart and home to an isolated little Royal Air Force (RAF) Base and an adjacent village that was completely walled off with a huge gate for access. It looked like a set from the movie King Kong.

Once we were tied up at the small pier, we were met by a wild-looking bunch of Brits wearing some bits of RAF uniforms, local articles of clothing, and checkered red-and-white headscarves. They definitely had a relaxed uniform standard! They picked us up in a big flatbed truck, and we sped off at high speed toward their base. When we finally arrived, I asked why they drove so fast. The answer was that it was harder to toss a grenade into the truck at that speed, and if they hit a mine, it might only blow the back of the truck off.

The bloke that told me that was not smiling.

Once at the entrance of the base, we were met by the ceremonial guards supplied by the sheik that ruled the village. Here’s a picture my shipmate Bob White took:

You thought I was exaggerating, didn’t you? The land there was as flat as a pancake, with mountains way in the distance. We spent the evening with the Brits. They had a piano and liked to get drunk and sing together. I think I was told that, unlike us, once you were assigned somewhere, you usually stayed there until you left the service, and some of those guys had been there for 10 years or more.

As I mentioned, the village was run by a sheik, an educated man who loved Elvis Presley. Each night some of the officers and one enlisted man would hop in their Land Rover and go to the village, where the enlisted man acted as a projectionist and showed a movie.

Every now and then Marxist rebels would swoop down from the mountains and shoot the place up, and then take off on their camels. The Brits would put a patrol together and chase after them. It sounded harmless until they mentioned that the RAF base to their west had been wiped out in a recent attack. I failed to mention that the villagers had no running water and did not know what electricity was. Each morning the villagers would open that huge gate and drag a big longboat out into the water and proceed to go fishing.

This is what Salalah looks like now:

To put this in perspective, their deep-water general cargo terminal can handle 20 million tons annually, and the liquid bulk terminal can handle another six million tons.

After Salalah, we paid a visit to Cochin, India, and Karachi, Pakistan. In Cochin, I remember a legless beggar sitting by the side of a dirt road with his beggar cup as a Mercedes with tinted windows thundered by. One of my shipmates and I spent the evening on the roof of a local hotel chatting with a Peace Corps volunteer who was giving up and going home.

Karachi was the most hostile place I have ever been. I think they had just had an election, and there were red hammer-and-sickle flags hanging everywhere. As we walked the streets in our sailor suits, the locals glared at us from every direction.

After leaving those two garden spots, we headed into the Persian Gulf, through the Strait of Hormuz, and north to the island country of Bahrain. Bahrain’s claim to fame seemed to be that the huge oil pipeline from Saudi Arabia ended there where ships could load up. We were able to visit an oil refinery for lunch. I remember that there were hovels outside the main gate with a sorry-looking camel tied up, but inside it looked like a scene from Leave It To Beaver — rows of small houses with white picket fences and a window box with flowers on each one. As we soon found out, Brits, Germans, and American engineers were at the top of the food chain, and so-called OFNs — other foreign nationals — did most of the work. OFNs were usually skilled Indians, Filipinos, or sometimes Bangladeshis.

Lunch consisted of the best steak I have ever tasted. I found out that the chef was lured away from some Michelin three-star restaurant in Europe to keep the honchos happy. Food was shipped in from all over the world for their dining pleasure.

Later, we took the strangest bus ride I have ever been on. We drove out into the middle of the island and saw nothing but pipes heading in various directions. Eventually, we stopped beside an exceptionally large pipe, with a large valve. Our guide had us all exit the bus and then he pointed to the valve and I think he said something like, “This is the valve!” We then reboarded the bus and returned.

I think it might have been the valve that controlled the world’s oil supply.

The things that seem to stand out after all these years include the few intense experiences, but mainly the funny ones. Looking back, I think getting a loaf of freshly baked bread from the cook in the middle of the night and eating it with my buddies rises to the top. It was while steaming along late at night, when almost all the crew were sleeping, that I enjoyed my time aboard Steinaker the most. It was then that all the stress and petty annoyances of being at the bottom of a rigid hierarchical organization faded away and I was free to simply do my job to the best of my ability.

I helped to keep my shipmates safe while they slept. Maybe that was enough.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com