The U.S. military is reportedly exploring the possibility of integrating AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missiles, or AMRAAMs, onto at least some of the Soviet-designed MiG-29 Fulcrum fighter jets in Ukraine’s inventory. There are serious caveats to this proposition, but it would, if feasible, give the Ukrainian Air Force a new beyond-visual-range air-to-air capability in the form of a highly-capable missile posing a major threat to Russian airpower venturing within its range. In addition, Ukraine’s military has already been receiving AIM-120s for use as surface-to-air missiles and would able to leverage the existing supply chains for those weapons, which The War Zone has previously highlighted the immense value of.

Politico was the first to report on the possibility of AMRAAM eventually appearing under the wings of Ukrainian MiG-29s. The outlet cited two unnamed Department of Defense officials and a third anonymous person involved in this effort. The story also said that the Pentagon declined to comment directly in any way on this supposed initiative.

This is, of course, not the first time that the U.S. military has assisted the Ukrainian Air Force in integrating an American-made munition onto its existing fleet of Soviet-designed combat jets. Ukraine’s MiG-29s, as well as its Su-27 Flanker fighters, have been employing AGM-88 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missiles (HARM), designed primarily to home in on enemy air defense radars and other emitters, for months now.

Just on Tuesday, the U.S. Air Force’s top officer in Europe disclosed that the Ukrainian Air Force now has Joint Direct Attack Munition-Extended Range (JDAM-ER) precision-guided bombs, as The War Zone was first to report.

How exactly Ukrainian aircraft are employing AGM-88s or JDAM-ERs is unclear. However, both weapons have modes of operation that require relatively limited input from the launching aircraft, as you can read more about in these past War Zone explainers. This, in turn, could have limited the hurdles to integration in those cases.

Integrating a radar-guided air-to-air missile like AMRAAM onto those aircraft presents new challenges. For one, at least some amount of work would need to be done to ensure that Ukrainian Air Force MiG-29s – and potentially other suitable aircraft in the country’s inventory, like its Su-27s – can just fire the weapon. This includes making sure the weapon can safely separate from the aircraft under various aerodynamic scenarios.

Far more problematic is the fact that the AIM-120, as designed, needs to be able to receive information from the launching aircraft’s radar before it even leaves the rail. To be highly effective over longer distances, it requires further communication with the launching aircraft throughout its flight.

“How do you mount this thing? Can you get all the electronics in the aircraft to talk to this thing that wasn’t meant to be launched?” are the problems to be solved, according to one of Politico‘s Defense Department sources.

All existing variants of the AIM-120 can be employed in the same general manner. The launching aircraft transmits information to the missile about the target’s location before it is fired. It then uses an internal autopilot to guide it to the right general area, at which point an onboard radar seeker activates, searches for, and (hopefully) locks onto the target. An onboard datalink allows for updated targeting information to be sent to the weapon from the firing aircraft as it journeys to the target. This is not a necessary mode to employ the missile, but it can greatly improve the AIM-120’s probability of kill, especially for longer-range shots.

Regardless, the ability to take shots with active radar-guided missiles and then break radar lock, and even run when needed, would be a great advantage to the Ukrainian Air Force.

Unfortunately, the other problem is the Soviet-designed radars in Ukraine’s combat jets simply don’t have the range to make the most of the AIM-120’s reach in the first place. A Ukrainian MiG-29 pilot known by his callsign Juice, who has spoken to The War Zone on multiple occasions, has highlighted this to us in the past.

“Actually, the lack of fire and forget missiles is the greatest problem for us,” he told The War Zone in a previous interview. “Even if we had them our radars couldn’t provide the same distances [as the Russian fighters].”

The AIM-120A variant entered U.S. military service in 1991. An improved AIM-120B version, with an upgraded guidance system with a new digital main processor and other improved electronic components, began being fielded in 1994.

In 1996, the first AIM-120C variants began being delivered. These missiles are easily distinguishable from earlier types by their clipped fins, a requirement to ensure the weapon could fit inside the F-22 Raptor stealth fighter’s main internal weapons bay. Subsequent subvariants of the C model included further improvements to the guidance and control components, new jam-resistant radar seekers, upgraded rocket motors for greater range, and other additions.

Examples of the first three variants of the AIM-120, especially subvariants of the C model, have been widely exported.

The latest variant, the AIM-120D, began entering U.S. military service in 2015. This version has significantly greater range and expanded engagement envelope compared to its predecessors, as well as other improvements to make it more accurate and maneuverable. It also features a new two-way datalink with the ability to receive targeting information from third parties.

Further subvariants of the AIM-120D are in development with further expanded capabilities. Some of those upgrades are making their way into C versions, too. The AIM-120C-8 subvariant already has some capabilities that are understood to be very close to that of the baseline D model. You can read more about all of this here.

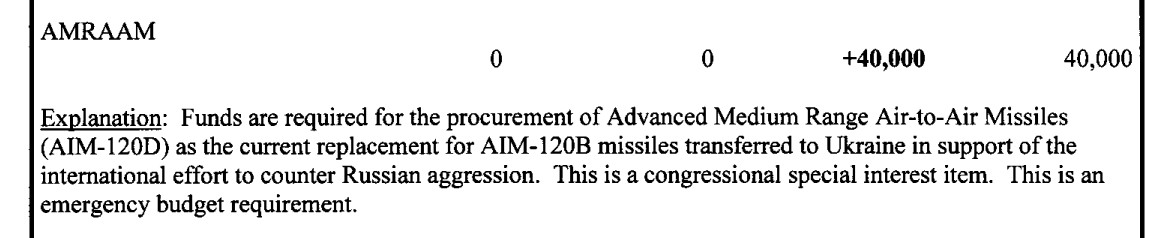

It’s unclear what variant or variants of the AIM-120 the U.S. military is exploring integrating onto Ukrainian MiG-29s. We know from Pentagon budget documents that older AIM-120B versions at least have already been supplied to the country for use in National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS).

Regardless, as has already been made clear, any version of the AIM-120 needs to be able to ‘talk’ to the launch platform to be most effective. It’s unclear whether the feasibility of adding the AMRAAM to any Soviet-designed combat jets has already been explored in the past, either by Hughes, the company that originally developed the missile, or Raytheon, its current manufacturer. The War Zone has reached out to Raytheon for more information.

If solutions or workarounds to these issues can be found that allow Ukrainian pilots in MiG-29s, or Su-27s, to employ AIM-120s in a way that retains even a significant portion of the weapon’s effectiveness it would be a significant development for the country’s Air Force. Right now, Ukrainian fighter pilots have to rely on Soviet-designed missiles like the infrared-guided R-73 and radar and infrared-guided variants of the R-27, weapons known to NATO as the AA-11 Archer and AA-10 Alamo, respectively, for air-to-air engagements. With Russia now the primary manufacturer of these missiles, Ukraine’s options for sourcing additional stocks can only be limited.

AIM-120s would provide valuable additional tools for engaging Russian aircraft and helicopters. An active radar missile with significant range would pose a major threat to Russian aircraft that get within its engagement zone and would have a chilling effect on air operations close to the front lines. In addition, the AMRAAM has demonstrated a robust capability to engage low-flying cruise missiles and drones. The Royal Saudi Air Force has been employing them against drones and cruise missile-like targets launched by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen heavily. These are both threats that the Ukrainian military has to contend with on a regular basis and are arguably more important to counter than fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters.

As already noted, the Ukrainian Air Force would be able to leverage existing AIM-120 supply chains, and potentially even stocks of AMRAAMs already in the country, if the missile can be effectively integrated onto any of its combat jets. The AIM-120 requires no special modifications to be fired from NASAMS launchers. With so many potential western sources for AMRAAMs beyond the United States, it would be easier for the Ukrainians to keep up a steady supply for air-to-air and surface-to-air.

One possible workaround would require advanced AIM-120s with the ability to leverage targeting data from third-party sources, like Ukraine’s NASAMS batteries and its forthcoming Patriot batteries. Still, this seems highly unlikely to be the case and a significant interface would still need to exist in the cockpit. Also, this would include more technologically sensitive versions of the AMRAAM.

Another way to address this issue could be to retrofit Ukrainian fighters with an off-the-shelf Western radar that is already fully capable of employing the AIM-120. This would require a new cockpit display and interface and wiring, but it could be done. Time would be a major factor here, but if Ukraine is years away from a western fighter, then this may be a prudent move.

If pairing AIM-120s with existing Ukrainian aircraft is at all feasible, it could present an alternative response to the persistent requests from the government in Kyiv for more modern Western combat jets. Juice, the Ukrainian pilot, has been among those advocating for deliveries of these aircraft in part because of the newer air-to-air missiles, like the AIM-120, they can carry.

“It’s too long and too expensive and too complicated to integrate any air-to-air systems on an old jet,” Juice had argued in an interview with The War Zone last year.

There are indications that a number of Ukraine’s international partners, including the United States, may be increasingly open to considering this possibility. However, U.S. officials, in particular, still view it as a longer-term discussion.

Politico‘s report earlier today specifically noted that the potential integration of the AIM-120 onto Ukraine’s MiG-29s was being viewed as one way to help address “Kyiv’s need for additional firepower and air defenses as both Ukraine and Russia prepare for major offensives this spring.”

Altogether, if AIM-120s can be effectively added to the available arsenal for Ukraine’s MiG-29 fighters, or any other combat jets it has in its inventory now, it would be a major boon to the country’s air and missile defense capabilities.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com