Raytheon has received a contract from the U.S. Air Force to build a “flight-test ready” mini-missile that an aircraft could use to shoot down incoming air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles. This effort is one of a number of aircraft self-defense weapon concepts that the U.S. military as a whole has been exploring in recent years as potential opponents, especially Russia and China, continue to develop and field new and more advanced missiles of their own

The Pentagon announced the deal in its daily contracting notice on July 21, 2020. The first task order under the contract is worth just over $93 million, but it could eventually net Raytheon up to $375 million, in total. The announcement says that the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), which is managing the project, expects the work to be completed by October 2023.

The full announcement is as follows:

“Raytheon Co. Missile Systems, Tucson, Arizona, has been awarded a $375,000,000 indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract for a miniature self-defense missile. The contract provides for the research and development of a flight-test ready missile. The first task order is $93,380,234. Work will be performed in Tucson, Arizona, and is expected to be completed by October 2023. This award is the result of a competitive acquisition and two offers were received. Fiscal 2020 research, development, test and evaluation funds in the amount of $26,712,000 are being obligated at the time of award. Air Force Research Laboratory, Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, is the contracting activity (FA8651-20-D-0001).”

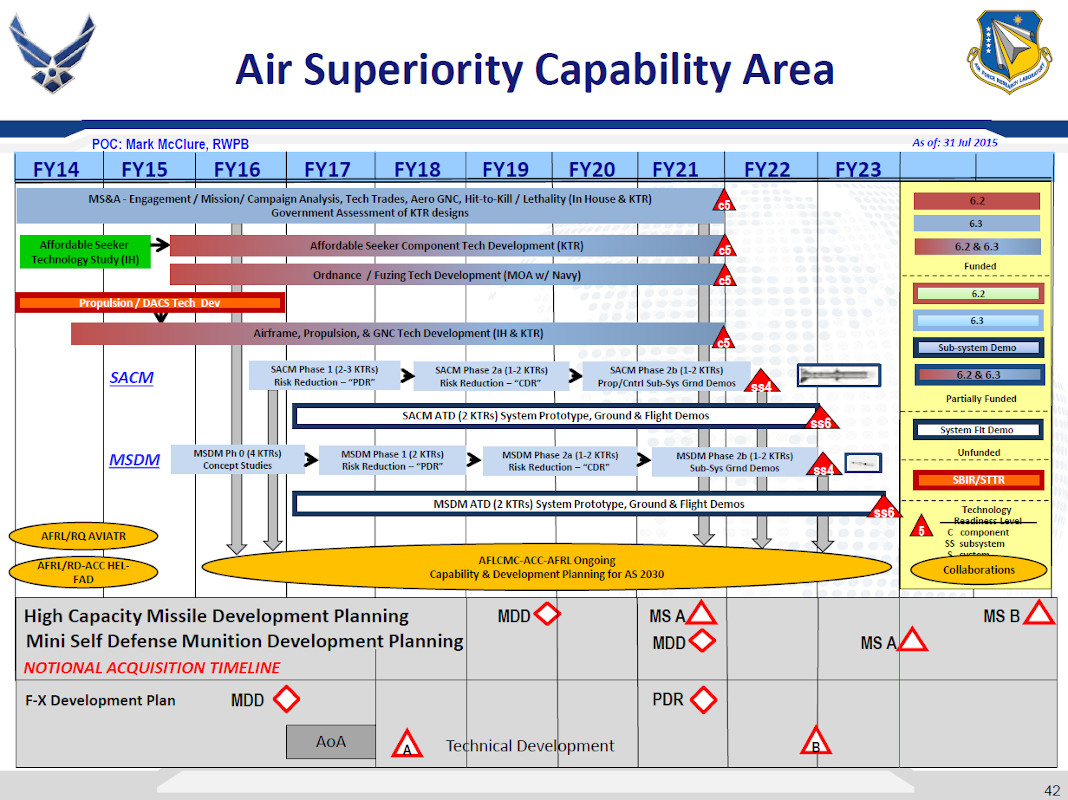

Though described here as “a miniature self-defense missile,” by every indication, this is the latest development in AFRL’s Miniature Self-Defense Munition (MSDM) program. This project first emerged publicly around 2015, at which time the goal was to have finished risk-reduction efforts by the end of the 2020 Fiscal Year and then move on to testing sub-systems for the mini-missile in the 2021 Fiscal Year.

In 2016, Raytheon had secured a $14 million contract for various missile work, including on MSDM. Lockheed Martin had also received a contract to work on the MSDM program. It seems that this was the company that had submitted the second offer that AFRL said it passed over in favor of Raytheon’s proposal for this new deal. Lockheed Martin had previously developed a ground-launched weapon to knock down incoming artillery rounds and small drones for the U.S. Army, known as the Miniature Hit-to-Kill (MHTK) interceptor, which you can read about more in this past War Zone story, a modified version of which would seem to fit well with the MSDM’s known requirements.

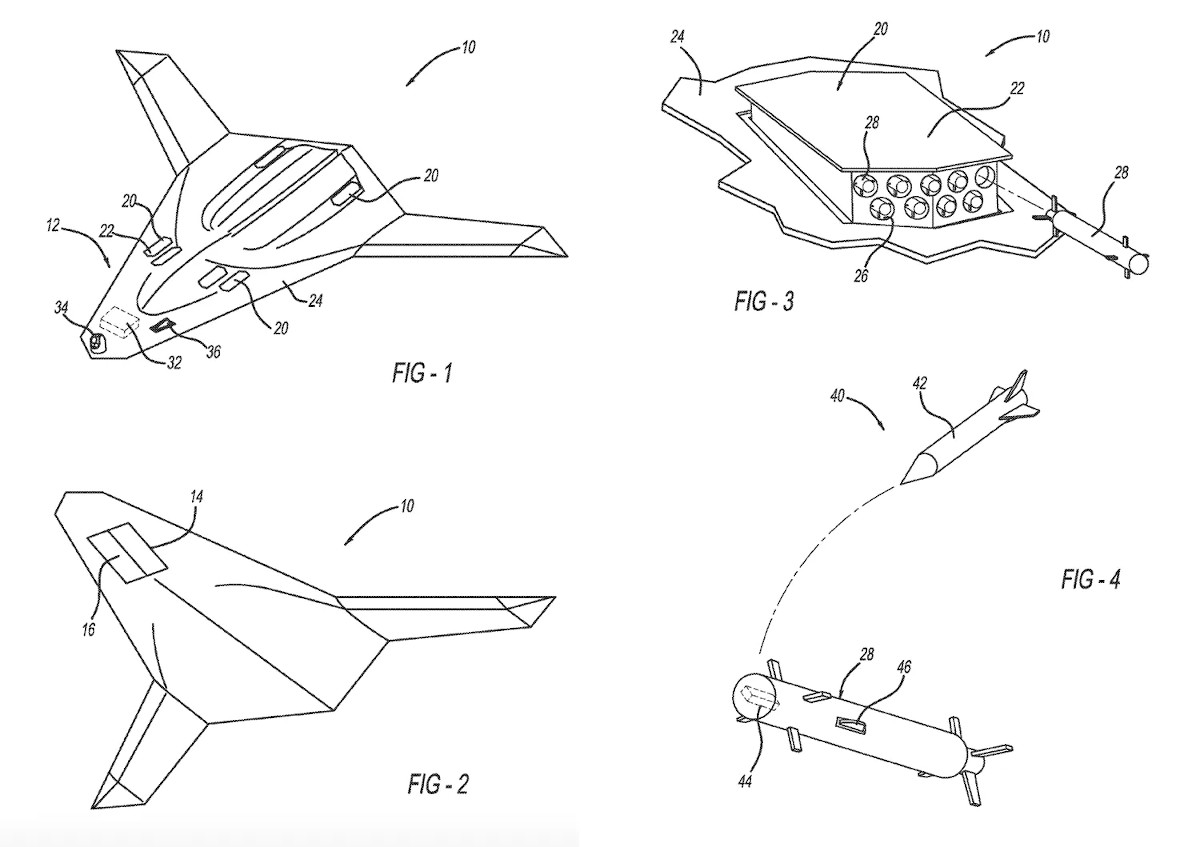

In 2017, Northrop Grumman also patented the design of an anti-missile interceptor system for aircraft that also seems similar to what AFRL has described it is looking for in an MSDM in the past. Boeing had also been reportedly involved in earlier stages of the program.

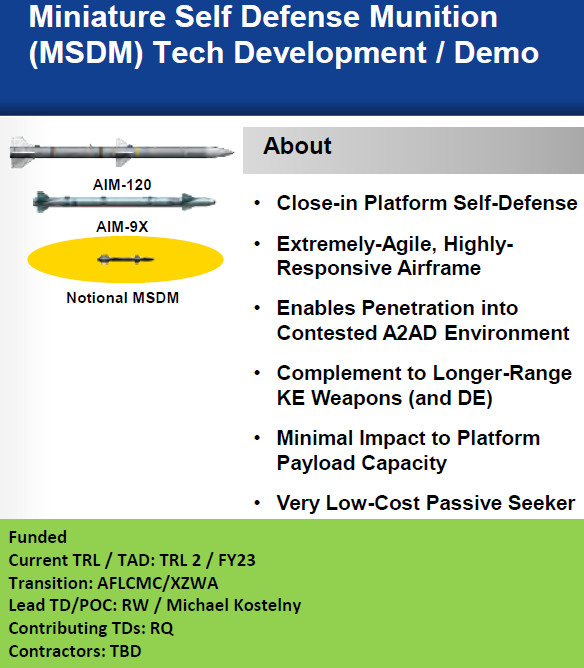

To date, AFRL has revealed relatively limited details about the MSDM program, its objectives, and its progress. It has described the notional weapon in the past as being an “extremely-agile, highly-responsive” missile that is also very small so as to have a “minimal impact to platform payload capacity.” The plan was also for it to be a hard-kill design, meaning that it would not have a traditional explosive warhead and would instead destroy its target by physically slamming into it.

AFRL has said in the past that the desired length of the notional missile was around one meter, or just under 3.3 feet. This would make it roughly a third as long as the AIM-9X Sidewinder dogfighting missile and even shorter than the AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM).

It’s unclear if that is still the length requirement for the MSDM. If it is, this would be mean AFRL is looking for a weapon about half the size of Raytheon’s own self-funded Peregrine compact air-to-air missile, a design the company revealed last year and has said is around six feet long. You can read more about Peregrine in this past War Zone piece.

AFRL has also said that a “very low-cost passive seeker” will be a key component of the MSDM. Associated renderings it has released in the past suggest this could be some form of imaging infrared seeker, which would give the missile a means of finding its target that is immune to electronic warfare jamming.

It’s unclear if this would be the MSDM’s only guidance option or whether it might include others, such as an active radar seeker. Multi-mode seekers, combined with two-way datalinks, have become increasingly popular on air-to-air, as well as air-to-ground munitions, as a means of defeating various countermeasures. However, an incoming missile is unlikely to have the same kind of self-protection features as an enemy aircraft.

No matter what the exact guidance configuration might be, low-cost seekers could help keep the MSDM’s overall unit cost down, which will be critical to making the system cost-effective given that an aircraft will likely carry a significant number of these interceptors and could need to fire more than one at a single threat to ensure that it is destroyed. It can already cost thousands of dollars for a plane to launch decoy flares and radar-confusing chaff cartridges, as well as expendable decoys.

This has also been an issue with regards to ground-based missile defense systems, as well as those specifically intended to shoot down artillery shells and rockets, mortar rounds, and similar lower-tier threats, a mission set commonly referred to as Counter-Rockets, Artillery, and Mortars (C-RAM). The Tamir interceptor that Israel’s Iron Dome C-RAM system uses is a good example of a lower-cost weapon, but its reported unit price is, at its very lowest, still around $40,000. Other reports have said each one costs between $100,000 and $150,000.

AFRL has already said that it sees the MSDM as just one element of a new slate of layered hard-kill self-protection options. This could also include a larger weapon it is developing under the Small Advanced Capabilities Missile (SACM) program, as well as directed-energy weapons, such as the one it is working on as part of the Self-protect High Energy Laser Demonstrator (SHiELD) effort. The Air Force recently announced a delay in the testing schedule for SHiELD.

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps have also been exploring similar hard-kill anti-missile defenses for both fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters in recent years and could leverage the Air Force’s work in the future, as well. There’s also the aforementioned hard-kill interceptor system that Northrop Grumman patented in 2017, indicating that there is growing interest, in general, among defense contractors in similar concepts, too.

Other self-protection systems, including advanced electronic warfare systems, including expandable options, as well as further support from offboard platforms will also be part of this overall defensive ecosystem. Improved networking capabilities will further help link all this together, making it easier to spot threats and do so faster.

A mix of MSDMs and these other systems could be increasingly invaluable for stealth aircraft, including future unmanned combat air vehicles, which may find themselves operating in dense hostile air defense environments with limited outside support. MSDM “enables penetration into contested A2AD [anti-access/area denial] environment,” AFRL said of MSDM in 2015.

Similar concerns are driving the Air Force’s development of a dedicated Stand-in Attack Weapon (SiAW) that its stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighter will be able to carry internally and that will give them another option for dealing with pop-up threats in heavily defended areas. SiAW is a derivative of the AGM-88G Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range (AARGM-ER), which the Navy is leading the development of and that will also be a multi-purpose weapon beyond its primary mission of destroying enemy air defense radars.

Of course, the MSDM would be just as applicable to any other aircraft capable of carrying it, including bombers and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms. It could be especially valuable for protecting vulnerable non-stealthy support platforms, such as aerial refueling tankers and airlifters. If the final design is cheap enough, it could be a useful countermeasure against short-range, man-portable surface-to-air missiles or even rocket-propelled grenades, which pose a very real threat to low and slow-flying aircraft and helicopters, especially when taking off or landing.

It’s unclear whether AFRL expects to receive the first MSDM flight-test ready prototype before its new contract with Raytheon wraps up in 2023 or when any actual flight testing will start. What we do know is that there is work going on now to move what could be an important self-defense option for U.S. military aircraft in the future out of the laboratory and into a more practical realm.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com