Ukraine is reportedly set to receive the U.S.-made Joint Direct Attack Munition — Extended Range, or JDAM-ER, an air-launched precision-guided bomb with a supplemental wing kit that means it can hit targets at around 45 miles. The disclosure follows previous announcements that the JDAM was headed to Ukraine as part of the supply of arms flowing there from the United States and its allies. Until now, however, it had been expected that a more basic version of the munition would likely be supplied, with a much more limited standoff range.

A recent story from Bloomberg cites “two people familiar with the matter” who, on condition of anonymity, confirmed the transfer of the JDAM-ER version, adding that the weapons are included in a $1.85-billion arms package that was announced on December 21. So far, the U.S. Department of Defense has not formally acknowledged that the wing-kit versions of the JDAM have been approved for Kyiv, with Pentagon spokeswoman Kelly Flynn telling Bloomberg that individual munition types would not be revealed, due to operational security concerns.

In the past, we looked in depth at the implications of providing JDAMs to Ukraine, specifically examining the advantages of the basic version of the munition. Fundamentally, this would bring a whole new degree of accuracy to the Ukrainian Air Force’s strikes on Russian targets, thanks to the JDAM’s guidance package that combines an inertial navigation system (INS) and a GPS receiver. As well as being accurate within tens of feet in any weather, the JDAM is a ‘fire and forget’ weapon, allowing the launch aircraft to turn away immediately after release. This offers a significant increase in survivability. And, thanks to the combined guidance, the weapon’s accuracy is still often acceptable even if the GPS signal is jammed or otherwise lost.

The JDAM-ER version offers all of those same benefits, but with the critical ability to hit targets at far greater standoff ranges. According to the manufacturer, Boeing, the JDAM-ER wing kit triples the effective range of the original JDAM, which was in the region of 15 miles, depending on the speed and altitude of the launch aircraft.

As well as opening up a new range of Russian targets to the Ukrainian Air Force, including second-echelon rear areas beyond the front lines, the JDAM-ER should help keep the launch aircraft further away from much of the deadliest Russian ground-based air defense systems. The presence of these — as well as Russian fighter jets with long-range air-to-air missiles — has forced the Ukrainian Air Force to fly most of its offensive missions at extremely low levels, for their own safety. This, in turn, makes it harder to hit targets and greatly reduces the range of any munitions that are launched. As we noted in the past, this would also have had an effect on JDAMs, which achieve their standoff range through launch at higher altitudes and at high speeds.

Using the JDAM-ER should help mitigate these issues, even if it, too, will suffer a reduction when dropped from a lower level. However, the fact that it’s fitted with a wing kit will automatically confer an improved standoff range, allowing it to glide toward its objective. Previously, we surmised that one tactic could involve a jet heading toward the target at low level, before popping up and releasing the JDAM in a lofted trajectory. This should also help the JDAM-ER reach further than would be possible with a standard ‘wingless’ JDAM.

Paired with AGM-88 HARM ‘shooters’ to suppress Russian threat radars, it’s possible aircraft could get closer to the front lines to make the most out of the JDAM-ER’s long range, hitting targets dozens of miles behind those lines.

It’s perhaps noteworthy that Gen. Christopher Cavoli, the commander of U.S. European Command, recently said that Ukraine needs longer-range missiles to strike more distant Russian positions, including headquarters and rear supply lines. While the JDAM-ER falls short of the 100-kilometer (62-mile) reach that Gen. Cavoli mentioned, it’s certainly a step in the right direction and could hold similar target sets at risk.

What’s interesting is that, unlike the more widely used basic JDAMs, the JDAM-ER version is not widely stockpiled and remains something of a specialist weapon. Up until fairly recently, the Pentagon had largely passed over the extended-range variant, although Australia, which helped develop it, fields it on its F/A-18F Super Hornets. Since then, the Navy and the Air Force have procured some of the kits, but not in very large numbers, as far as we know. This means that it’s not immediately available in significant quantities, suggesting that the decision was taken to provide a more costly, harder-to-source weapon due to the operational advantages that it will bring.

On the other hand, we do know that last month Boeing was awarded a $40.5-million U.S. Air Force contract for an undisclosed number of JDAM wing kits. This work is to be completed by June 30, 2023. The wing kits in question may well be intended for the winged version of the Quickstrike naval mine, a weapon that is becoming increasingly important for the Air Force. Potentially, wing kits from this contract could be diverted to Ukraine, or, considering the recent report, these could be intended for Ukraine entirely.

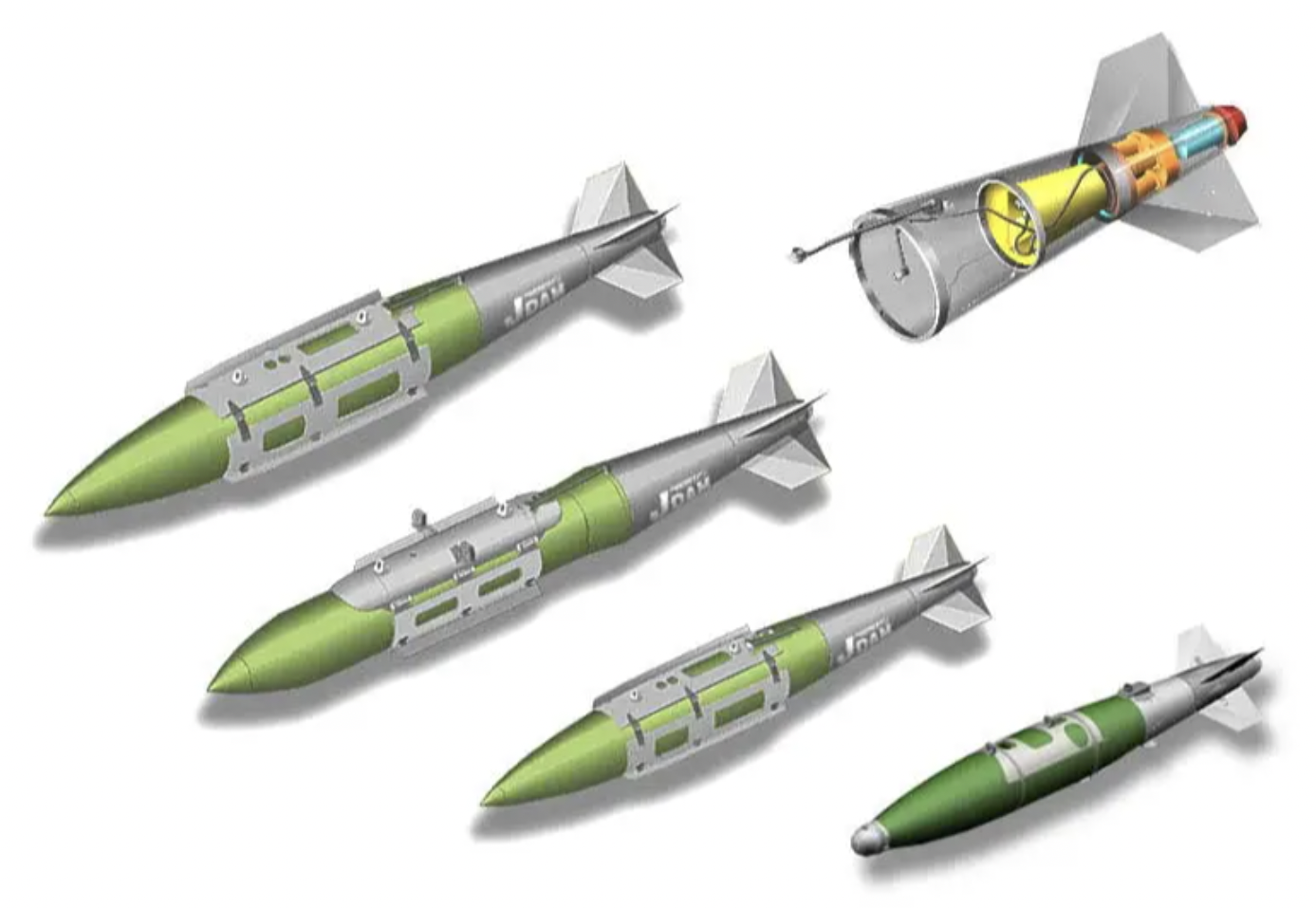

A JDAM kit consists of a guidance package and control section, tailfins for steering, body strakes to increase range, and, in the case of the JDAM-ER version, a pop-out wing assembly that is fitted below the bomb body when attached to an aircraft. These components are normally mated to a variant or derivative of the ubiquitous Mk 80 series of weapons.

We don’t know what type of bombs Ukraine’s JDAM-ER would be used with, either, with the JDAM kit typically being mated with the 2,000-pound Mk 84, 1,000-pound Mk 83, and 500-pound Mk 82 ‘dumb’ bombs, as well as the penetrating versions of these same weapons. These bombs, at least, are far more widely available and NATO stockpiles should ensure they can be sourced rapidly and in large numbers.

Even with the smallest bomb that it can be paired with, the 500-pound general-purpose Mk 82, JDAM-ER packs a significant precision-guided punch. In its 1,000-pound and 2,000-pound form, it provides Ukraine with a standoff precision-strike weapon capable of taking on large and fortified target sets. The M31 rockets fired by the widely used M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems, or HIMARS, and the M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) — currently Ukraine’s only Western long-range precision ground-attack weapon — pack a warhead of just 200 pounds. Ukraine is getting Ground-Launched Small Diameter Bombs (GLSDB), but these rocket-assisted glide bombs pack a similar warhead size, although they can fly out over twice the range. Because of these warhead size limitations, we have seen M31s used repeatedly en masse just to disable larger targets, like bridges, or to damage larger buildings, when a single 1,000-pound or 2,000-pound JDAM-ER would do the job definitively.

In other words, JDAM-ER would give Ukraine the same range as M31 rockets, but with a warhead that can level large structures, dispersed air defense sites, and even well-fortified emplacements. This is a massive leap in capability and opens up a huge range of critical target sets. It also does this without giving Ukraine the M142 Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missiles that have a similar warhead size but a range nearly five times that of the JDAM-ER. Providing this weapon is seen by the Biden Administration as highly volatile as its use against Russian targets within its own borders could quickly widen the conflict. There are also not many of them in inventory and they are seen as a critical stockpile should the U.S. have to go to war itself.

So, the JDAM-ER would solve a lot of problems.

There’s a slim possibility that JDAM-ER kits might be adapted for Ukraine’s existing stocks of Soviet-era freefall bombs. While this would ensure a ready supply of bombs, it’s unclear whether such a modification would be possible, or how long it would take to finesse. Interestingly, however, Russia appears to have recently developed a crude underslung JDAM-ER-style wing kit for its Soviet-era freefall bombs, although there is no indication that this includes any kind of precision guidance package. You can read more about the Russian wing kit here.

Once the JDAM-ER kits have been sourced for Ukraine, there are then the issues of building up the full weapons, ensuring they are cleared for use on the chosen Ukrainian Air Force platform(s), and providing the relevant training to the aircrews, weapons technicians, and maintainers.

As to the aircraft that are likely to carry the JDAM-ER, the current options comprise the Ukrainian Air Force’s MiG-29 or Su-27 fighter jets, its Su-24 strike aircraft, or possibly subsonic Su-25 ground-attack aircraft, although their lower performance would be less than ideal.

Clearly, whatever aircraft is chosen will have to undergo appropriate modifications, including at least a basic interface between the jet, the weapon, and the pilot in the cockpit. As we have addressed before, the simplest solution would likely involve the JDAM-ER being used only against pre-planned targets, with the target coordinates uploaded before the aircraft takes off — it is assumed that a similar approach was taken when integrating the AGM-88 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile, or HARM, on Ukrainian fighter jets. The ability to target or re-target in flight when employing JDAM-ER would require more extensive modifications. But the standard JDAM is built for hitting static targets, to begin with, so this really isn’t a major limitation.

The previous AGM-88 HARM integration could also provide the Ukrainian Air Force with a head start for the JDAM-ER since the LAU-118 pylon that carries the anti-radiation missile should also be suitable for carrying Mk 80 series bombs, or JDAM equivalents.

While glide bombs do run the risk of being shot down by enemy air defenses, doing so has proven to be much harder in reality than in theory. This is true even for targets that are defended by point-defense systems that are marketed as being specifically able to do so. While losses could occur, there is no risk to the launching party and the target could just be re-attacked, especially with multiple weapons converging on the target at the same time.

Right now, we are awaiting confirmation from the Pentagon that the JDAM-ER is indeed part of an arms package signed off for Ukraine. It could be that we will have to wait until we see evidence of its use in the conflict before we can be sure of that.

Previous experience with the AGM-88 HARM suggests that Ukraine should not have huge difficulties in introducing a weapon in the class of JDAM-ER. While it might not have the benefits of such ready availability as the basic JDAM, its much longer reach could prove critical to Ukraine’s fight.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com, tyler@thedrive.com