The U.K. Royal Air Force officer in charge of defining requirements for the Tempest future fighter says the program’s top priority is a large payload — roughly twice that of the F-35A stealth fighter. The same officer says the service is eyeing “really extreme range” for the new aircraft, with potentially enough internal fuel to fly across the Atlantic without refueling. These requirements provide some more ideas about the size and capabilities of the sixth-generation stealth fighter and also parallel similar concerns that have driven the development of the U.S. Air Force’s Boeing F-47 under the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiative.

The comments came from an officer known only as Group Captain Bill, who heads up the Requirement and Concepting team for the U.K. Ministry of Defense. This department is charged with defining the capabilities that the Tempest needs to meet the Royal Air Force’s evolving operational requirements. He was speaking earlier this month on a special edition of Team Tempest’s Future Horizons podcast, partnered with the Royal Air Force’s InsideAIR official podcast.

GCAP, or Global Combat Air Program, is the effort under which the United Kingdom’s Tempest next-generation fighter is being developed, in partnership with Italy and Japan — the podcast raised the possibility that, once in service, the aircraft itself might not be known as Tempest, although that would still seem the most likely name for the Royal Air Force, at least.

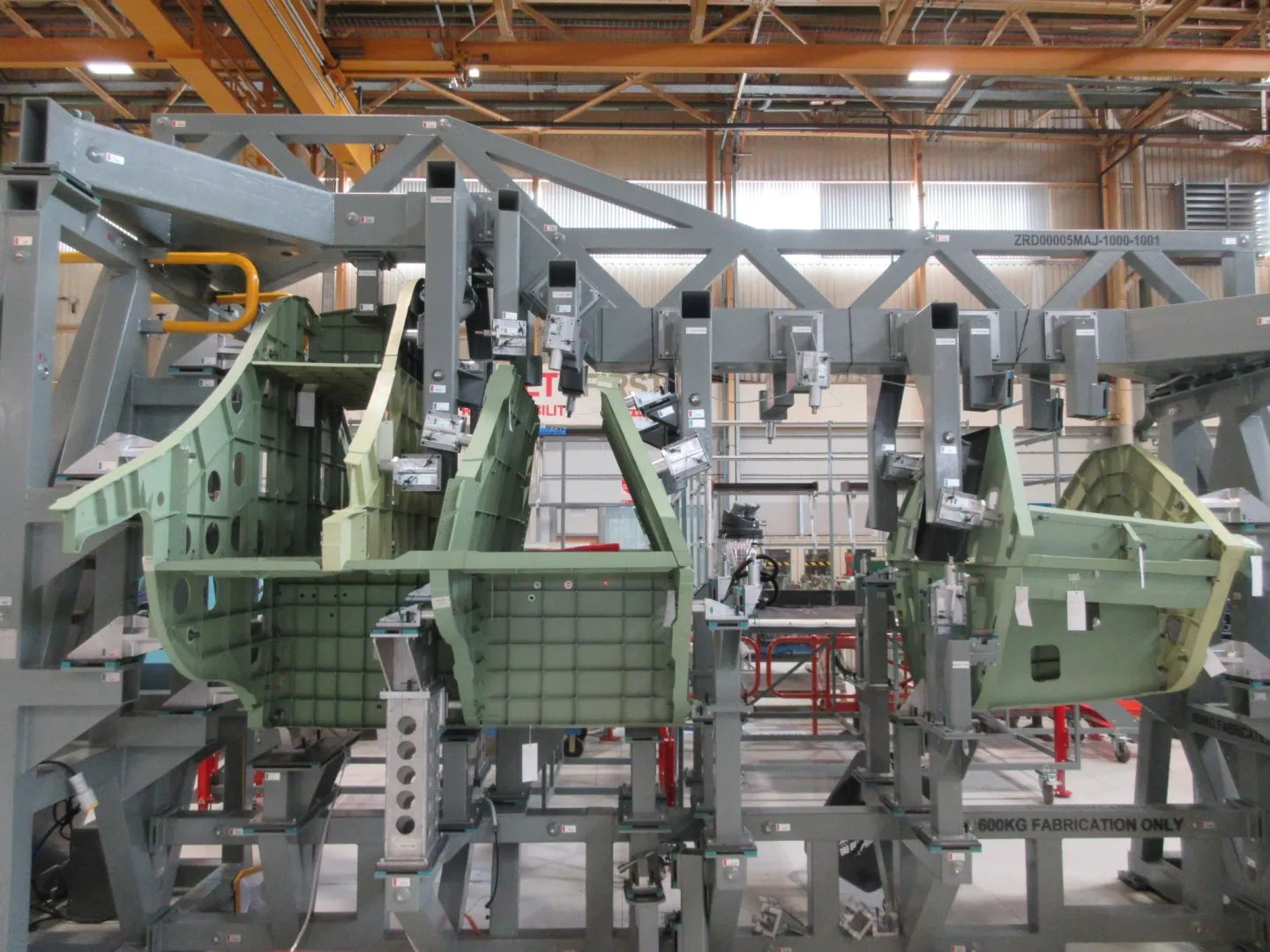

A demonstrator for the Tempest program is now being built, although its precise relationship to the final aircraft is not completely clear. The aircraft is supposed to take to the air in 2027.

Meanwhile, a Boeing 757-based flying testbed for the Tempest program, named Excalibur, is also now flying, with its sensors planned to include the Multi-Function Radio Frequency System radar from Leonardo, plus communications systems and electronic warfare equipment.

More broadly, for the United Kingdom specifically, the Tempest will be part of the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) program, a wide-ranging air combat initiative that also includes next-generation weapons, uncrewed platforms, networks and data sharing, and more.

Bill described the plan for Tempest, as the core platform within the FCAS system of systems, to be a “quarterback.” This is a term that’s cropped up before for emerging and future combat aircraft missions, as well as existing 5th generation fighters. The latter use their superior situational awareness and survivability to operate forward as a force multiplier for less capable assets. In terms of 6th generation tactical jets, it also refers to the ability to control uncrewed Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCAs) and/or other drones, as well as networked weapons.

“It’s the platform that walks onto the field knowing the plan,” Bill continued. “It understands what plans it has available, it’s no longer able to maintain the connection back to the coach on the sidelines because you’re too deep into the field, and the other players that are there in that team, some of those will be expendable. They will not make it through the play that we’re executing, and that play will not go to plan either. The quarterback needs to have the ability, the strategic vision, and the reactions to be able to deal with what plays out when they start and then pick how it’s then going to deliver the tasks to what remains on the field, to look at what’s going on and then decide how it achieves the aim. It’s survivable enough to take a hit if needs be, it’s no kind of fragile back-row player. Also, if need be, it can score a touchdown itself. But the aim here is that it’s going to orchestrate many others, many other parts in that system of systems.”

“This aircraft is going to approach replacing Typhoon in a different way,” Bill said. “The threat environment means that range has become a really big thing for all of us.”

This is something that’s being recognized in sixth-generation combat aircraft programs around the world, whether in NGAD in the United States or in broadly similar Chinese developments.

For the Tempest program, the kind of threat environment envisaged means that the fighter will likely “have to leave the tanker a long way behind” in various combat scenarios. This is pushing the demand for “really extreme range, kind of maybe getting across the Atlantic to America on internal fuel.” This compares with the Typhoon, which would normally need three or four tanker hook-ups to cover the same distance.

“We’re building an aircraft that is going to have an awful lot of range,” Bill continued, “but at the top of our list is the payload.”

“Payload is what we’re all about,” Bill emphasized. “In fact, in pure capability terms, I don’t care how I get [the payload] there. It could be in the back of an A400, from a submarine, or from space. It just so happens that our analysis tells us the best way to get that payload there right now is in a fast jet. But the payload, now you’d expect weapons to be in there. So that’s obvious, and boy, will we have weapons.”

According to Bill, the Tempest will have roughly double an F-35A’s worth of payload. It’s unclear how this would be broken down in terms of fuel and weapons, but just in terms of internal and external ordnance, for the F-35A, this equates to more than 18,000 pounds, according to the manufacturer. Considering the Tempest’s mission, as described above, this is likely referring to internal payload, which would put it at around 10,000lbs compared to the F-35A’s 5,000lbs — two 2,000lb-class guided bombs plus a pair of AIM-120s. This would be an impressive load and would give Tempest quite an arsenal of its own.

The weapons that would fill its big bays are also expected to include new types of missiles now in development. Here, there will very likely be a focus on ultra-long-range air-to-air missiles.

Plans to arm the Tempest with larger air-to-air missiles offering a longer range than those currently used by any of the three GCAP partner countries were revealed earlier this year, as you can read about here.

While Bill said the Tempest should not be characterized specifically as a specialist for beyond-visual-range combat, it’s clear there is also an expectation that it should defeat aerial threats at longer ranges than the Typhoon, for example:

“I think the idea of defeating an enemy by turning harder, we have to ask ourselves, is that necessarily the way you want GCAP to fight? Tempest may be able to defeat a threat without needing to turn at all, and that’s a really bold statement to make, remember, because we made that statement once before in the 1960s with Phantom where we said maneuverability was no longer a thing, and that missiles would be able to do the job, and radars would be able to do the job. That turned out to be the wrong assessment, and we had to go through a whole cycle to get ourselves back to a place where we understood how we were going to use combat air. So we’re not making any of these kinds of statements lightly. There’s an awful lot of analysis that goes on behind it, but I wouldn’t characterize GCAP as only a long-range platform at all.”

The prodigious payload for the Tempest will not just be made up of fuel and weapons.

Just as important will be the sensors, especially bearing in mind the envisaged quarterback role.

“Everywhere GCAP goes, it carves a picture of the world to support other military capabilities, to be able to exploit that, use that,” Bill explained. “And so getting the sensors forward is as important as getting the weapons forward. And those sensors also mean that when we go deep into enemy territory, and we may not be able to reach back to anyone else’s help, [or if] there’s no connection with the E-7 in the future, we still can complete the kill chain, so the ability to find and fix something, to identify it, to engage it, and then work out how that engagement went. We can still do that within our platform or within our formation.”

The final piece of the payload puzzle will be the Tempest’s function in what Bill described as a ‘flying server rack’, specifically in support of complementary drones and other autonomous capabilities, including ones pushed even further forward into the battlespace.

He continued: “We’re going to take the compute forward and then take the server rack forward. Because if you want low-cost autonomous systems, we all know from turning our iPhone on, how much data you pull to use ChatGPT. Well, where’s that server going to be if you’re deep in enemy territory? So if you want low-cost autonomous systems, they need a server to back them up, and they need sensors to back them up to make them capable. So that quarterback has a really important role now, because you’re carrying the sensors and the servers to enable that system-of-systems that’s forward in that contested area.”

The importance of the Tempest as a resilient data-gathering and data-sharing hub also ties into its planned quarterback role, and this function becomes all the more critical bearing in mind that the aircraft will be expected to use its various capabilities, including stealth, to penetrate deep into enemy airspace.

“So the idea of us being able to guarantee a connection back to our side, that’s not reasonable,” Bill explained. “What I can guarantee is a connection back to the GCAP, that core platform. That’s why I call it a quarterback. So we’ll be able to maintain, we have to maintain a local network.”

Bill also reflected that the F-35 is already a good example of an aircraft that can gather huge amounts of data and distribute this to other assets, although the Tempest will take this a step further.

“The F-35, when it’s in a formation, is greater than the sum of its parts,” Bill said. “But in some ways, that F-35 formation is a little bit selfish with the way it does that, with GCAP and sixth-generation, where we’re heading for is something that’s greater than the sum of its parts, but that benefit is shared across the domains, so with maritime, with land, with space and with other air assets. Our ability to connect is going to be fundamental to our success. And when we’re outside of the threat environment, we’ll be connected in a very broad, low-latency, high-speed, high-bandwidth way, and as we go in, we’ll narrow that down and manage that for our survivability.”

The fact that the connection back to a command center or other distant operational node cannot always be guaranteed is also the reason why, for now at least, the Tempest will have a pilot. Bill suggested that this will be a single pilot, although in terms of function, they will be closer to being a weapons system officer (WSO) than a traditional pilot.

“We’re prepared, though, for the time when artificial general intelligence does catch up,” Bill added, pointing to the possibility of a future uncrewed version of the Tempest, an idea that U.K. officials have also raised in the past. Earlier this year, Chief of the Air Staff Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Knighton said it was “absolutely” possible that an uncrewed version of the Tempest platform could be developed in the longer term.

Bill also tackled the issue of drones and whether the proliferation of uncrewed platforms threatens the continued relevance of crewed combat aircraft like the Tempest.

While admitting that, for the cost of a fast jet, an air force could pay for perhaps 10,000 drones, the future threat environment will demand a balance of high and lower-end capabilities. After all, the key demands of air combat will be long range and some form of survivability, whether through stealth or speed, or a combination.

“By the time you’ve made your long-range, high-speed, somewhat stealthy or completely expendable drone, you probably end up at a cost point, which isn’t necessarily where you’d expect,” Bill reasoned. “So there’s a balance to this. In all of it, if you want it to be low cost, you really want the sensors to be somewhere else, maybe in a GCAP. If you want that compute to be somewhere else, so they’re smart, they’re not dumb, you’re going to need a server rack in the right place where you can connect to with without getting them killed, because talking too loud can get you killed in a modern threat environment. So you need a server right there. Maybe that’s GCAP as well.”

Despite that, Bill noted that there is “absolutely a place for saturation through autonomous and expendable systems,” characterizing this as “definitely one of our three S’s.” These are stealth, suppression (for example, electronic attack assets), and saturation.

“We’ve done that for years with weapons already, but drones are the new form of saturation. Put those three things together, and you have got yourself a really nice mix. But if you pick any one antibiotic and just overuse it, what you breed is antibiotic resistance, you get yourself whacked by something that’s evolved to deal with you. So you need to have a spread.”

Interestingly, Bill mentioned all of these capabilities coming online somewhat later than in previous plans. He spoke about the goal for Tempest to replace the Royal Air Force’s Typhoon in the 2040s, while earlier official statements had suggested an in-service date of 2035.

Whatever the case, there’s no doubt that developing the full range of planned exotic technologies in time and in an affordable manner will still be a huge challenge. And this is before negotiating the various political obstacles that likely still threaten to interrupt the Tempest program’s progress.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com