By now, the use of hard-kill active protection systems (APS) to protect vehicles on the battlefield is well known, with projectiles used to defeat fast-moving threats, like incoming anti-tank missiles. Much more unusual, however, is a loosely related concept: The Soviet Union’s little-known program to develop a system that would, it was planned, swat down incoming ballistic missile warheads to protect its own intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union relied heavily on its extensive ICBM force as a key part of its strategic nuclear triad, complemented by submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) and long-range strategic bombers. That tradition continues today. While the Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces introduced increasingly more capable and destructive ICBMs, they were always aware of their vulnerability, as long as they were based in silos or other fixed sites.

Such concerns drove the development and fielding of road-mobile and rail-mobile ICBMs, but there were also efforts to better protect the static ICBM fields against potential attack, including from the U.S. ICBMs that would have been their primary threat. The existence of one such measure was brought to our attention by @krakek1 on X. The same user pointed us to this Russian-language article that provides an authoritative backgrounder on the program.

The program was named Mozyr, after a town in the then Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic. Also known as izdeliye (Project) 171, it was the responsibility of KB Mashinostroyeniya (KBM), a state defense enterprise located in Kolomna, in the Moscow region.

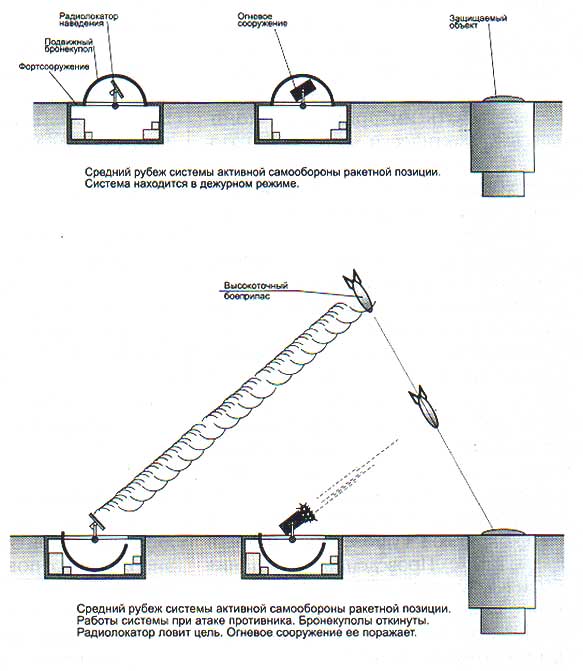

In simple terms, Mozyr aimed to develop an APS that would protect ICBM silos against incoming ballistic missile warheads, using a shotgun-like multi-barrel launcher that would fire tungsten rods into the paths of the warheads, bringing them down when they were in the lower atmosphere.

Development of Mozyr began in the mid-1970s and was under the direct supervision of the Soviet Minister of Defense, D.F. Ustinov, reflecting the program’s high priority. At the same time, as well as KBM, no fewer than 250 enterprises from 22 different state ministries were involved in developing the system.

It seems that the main application for the Mozyr system, once fielded, would be the protection of the future R-36M2 Voevoda ICBM silos. Known to NATO as the SS-18 Mod 5/6 Satan, this system entered service in 1988. The Mod 5 version carried 10 multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV), each with a yield of 500-750 kilotons. The Mod 6 is fitted with a single re-entry vehicle with an eight-megaton warhead. With a range of almost 10,000 miles, the R-36M2 promised an accuracy of 1,640 feet circular error probable (CEP).

A video showing the test launch of an R-36M2 Voevoda ICBM:

Today, the SS-18 Mod 6 remains in Russian service, one of the last two Soviet-era ICBMs that are still operational, the other being the UR-100N (SS-19 Stiletto) that carries the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV).

As for the Mozyr system, it would never get the chance to defend the Voevoda ICBM silos as a frontline, operational system. However, it was built and tested.

As completed, the Mozyr system consisted of a multi-barrel launcher (some sources state that it had “several hundred” barrels, others that it had 80). Each barrel was loaded with a propellant charge and a projectile made of high-strength steel alloy.

The system included its own target detection, guidance, and fire-control systems. The last of these determined the required density of the ‘cloud’ of projectiles, as well as the direction in which they would be fired, depending on the nature of the threat. This was all achieved automatically, with limited human operator input.

The projectiles destroyed the incoming warhead kinetically. This was ensured by a closing speed of around six kilometers (around 20,000 feet) per second.

Historical sources referring to Mozyr note that many details about it remain unconfirmed, but there is multiple evidence of the system having been tested.

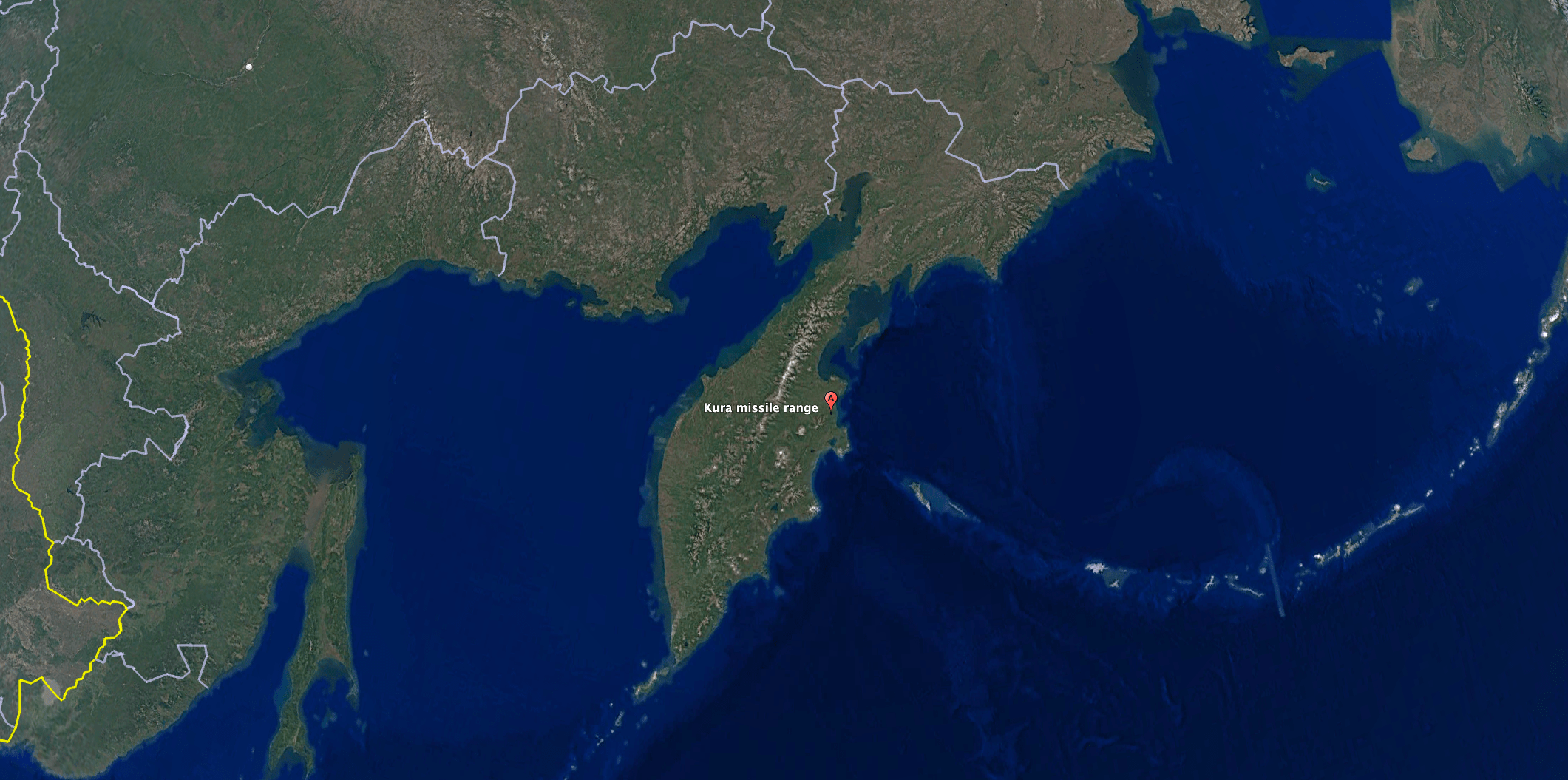

By 1981, work had been authorized to prepare for the testing of the Mozyr system, but the first real steps to establish an experimental test site weren’t taken until 1984. The chosen location was Kura, on the Kamchatka Peninsula, in the Russian Far East. Construction work here was carried out around 12 miles from Shiveluch, the northernmost active volcano in Kamchatka. Around 250 flights by cargo aircraft were required to move related equipment to this remote site, which was also served by a helipad.

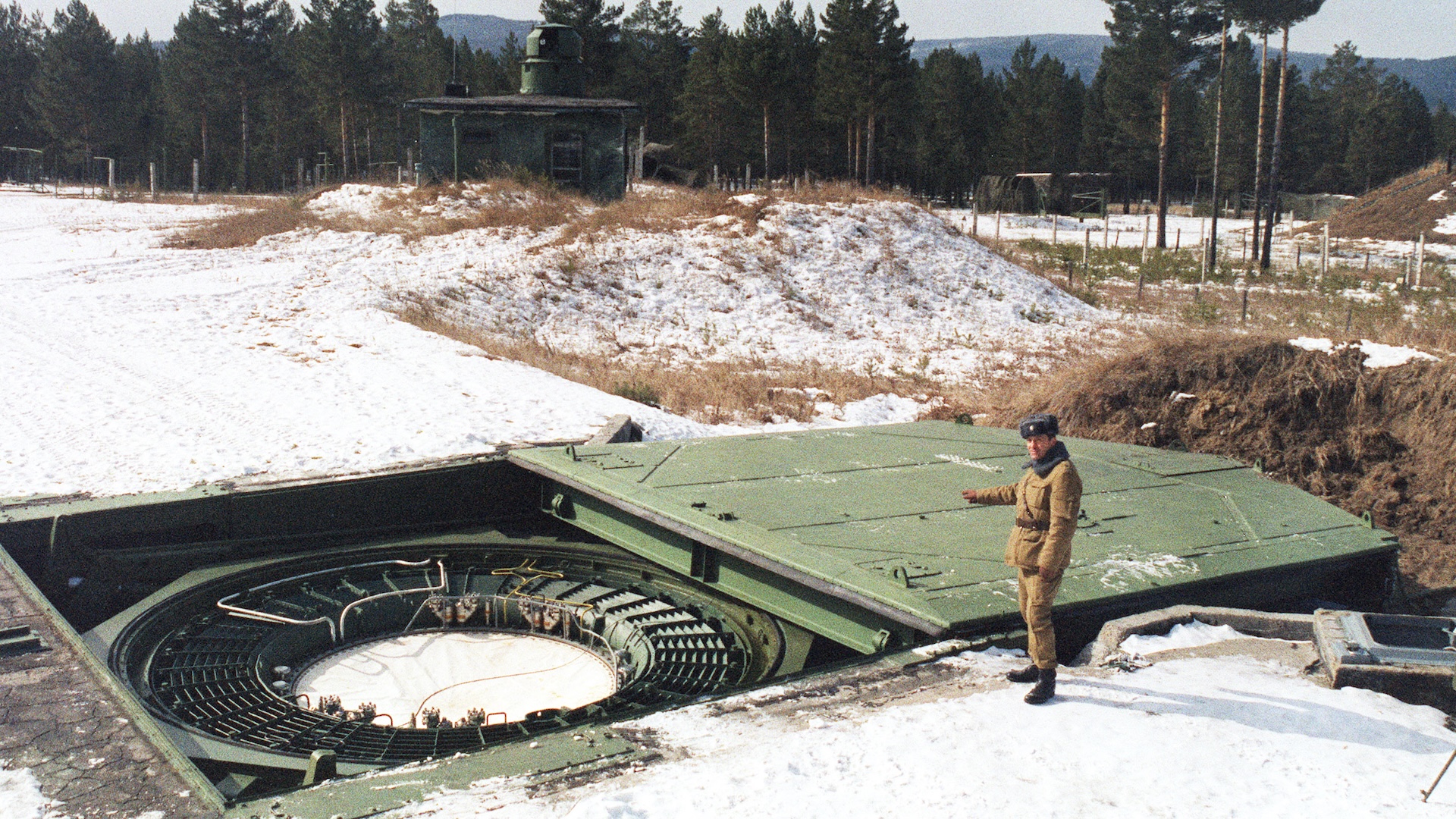

It appears that several prototypes of the Mozyr system were tested at Kura between 1985 and 1988. The test program involved the construction of a simulated ICBM silo, with a prototype of the active defense system located around the launch facility. Meanwhile, a command post for the system was located around 3.5 miles from the silo.

More recent photos of what’s presumed to be the test site show various abandoned buildings, towers to carry antennas for the detection system, as well as a mobile support vehicle ‘borrowed’ from the Pioneer (SS-20 Saber) mobile intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) system.

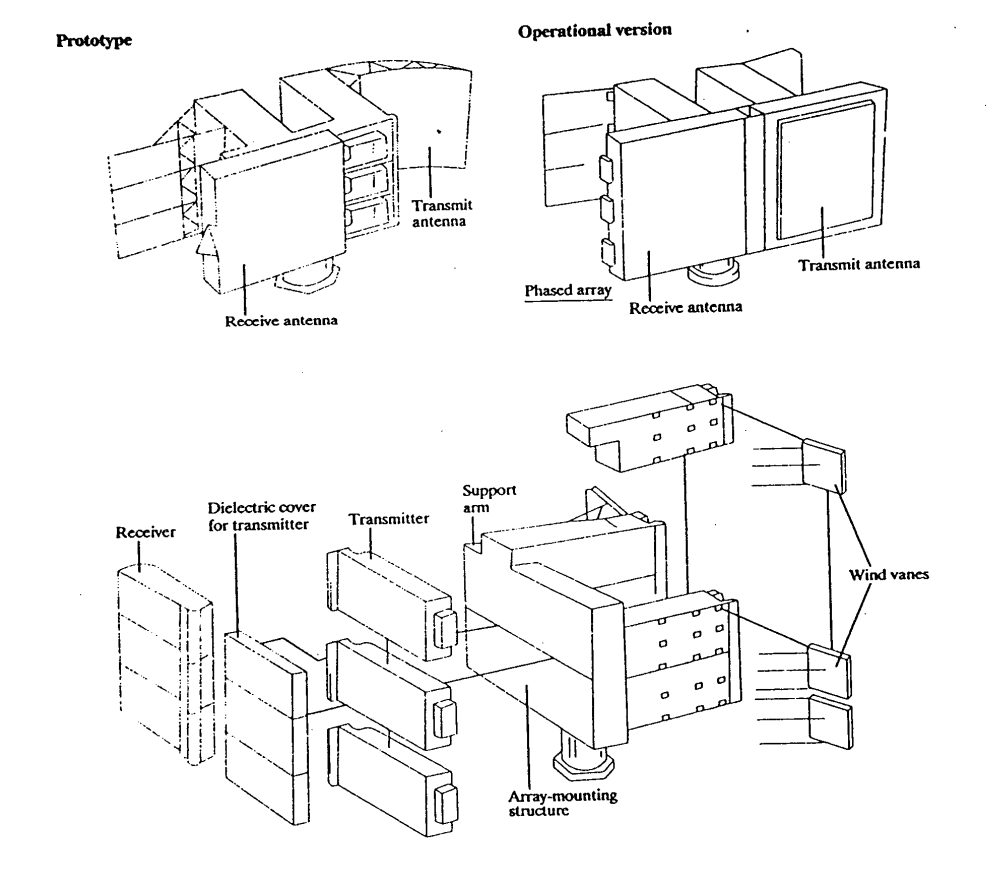

The radar used in the tests is understood to have been the 5N65 (Flat Twin), a phased-array type that was developed as part of the Soviet anti-ballistic missile system, but which was never commissioned. It is known to have been installed and tested at Kura, as part of the broader 5K17 tracking and measuring system.

Unarmed ICBMs were launched toward the site, being fired either from the Plesetsk test site or from Baikonur in Kazakhstan (sources differ).

Reportedly, the targets used to test the Mozyr were provided by decommissioned SS-18 Mod 4 ICBMs. This version of the missile could carry up to 10 MIRVs, although it’s unclear how many were actually ejected during each of the interception tests.

The following account of the test is provided by the militaryrussia.ru website:

“It all happened at night. The rocket flew from Baikonur for about 20 minutes. A five-minute readiness was announced. The stars shone in the clear, cloudless sky. Suddenly, a new star flashed brightly among them. It quickly increased in diameter and exploded like fireworks, lighting up half the sky. For a few seconds, night turned into day, and it became light. A fireball the size of the moon emerged from the fireworks, explosions were heard, and protuberances burst out from the ball in different directions — the target had been hit.”

According to available accounts, the various tests proved that an incoming ICBM warhead could be successfully intercepted in the descent phase of its trajectory. An academic report into the results of these tests stated that the destruction of a nuclear warhead by the Mozyr system “was highly likely to prevent the initiation of a nuclear detonation.”

State testing of the experimental Mozyr system was completed in September 1991, after its funding was discontinued. This was not a reflection of any particular problems with the concept, but rather the failed coup attempt of that year, which precipitated the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Interestingly, Russian accounts suggest that the Mozyr system was not in contravention of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, although this doesn’t seem entirely clear. The treaty permitted the Soviet Union and the United States to each have one limited ABM system to protect their capital and another to protect an ICBM launch area; this was later reduced to one system.

It should be noted that the United States also looked at a very similar kind of APS as a means of protecting its planned MX (later LGM-118 Peacekeeper) ICBM sites. This was known as Swarmjet and would have comprised launchers containing thousands of spin-stabilized unguided rockets. Unlike its Soviet equivalent, it never reached the hardware stage.

In 2012, there were unconfirmed reports that Russia might restart work on a similar kind of APS to defend its ICBM sites, although nothing appears to have come of this.

Nevertheless, it’s interesting to consider how an APS of this kind might align with current concerns about missile defense, especially with the demise of the ABM Treaty in 2002.

For Russia, this might be of particular interest.

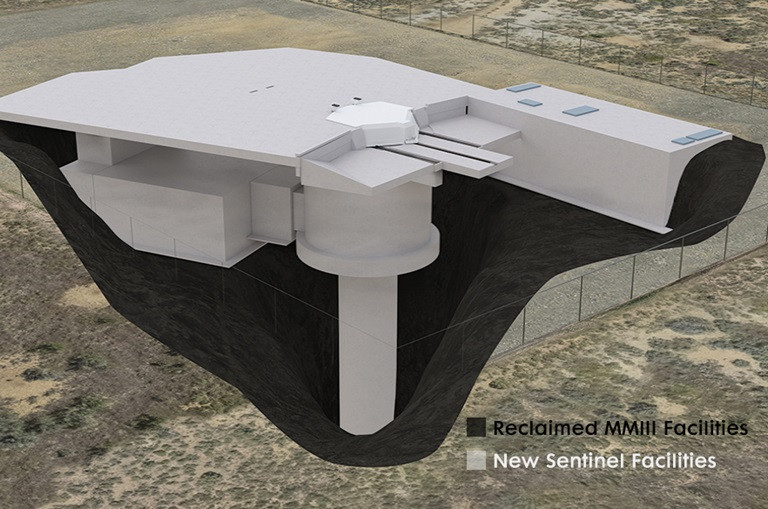

As its most powerful nuclear adversary, the United States is looking forward to introducing its future LGM-35A Sentinel ICBMs and is also increasingly considering the option of arming them with multiple warheads. These will replace the U.S. Air Force’s current LGM-30G Minuteman III ICBMs. The operational examples of the Minuteman III are presently only loaded with one warhead due to arms control agreements with Russia.

Then there are the Trident D5 SLBMs carried by the U.S. Navy’s Ohio class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), which also have MIRV configurations. The Navy’s future Columbia class SSBNs are also set to be armed with improved variants of the D5.

As for China, Russia’s nuclear neighbor, it fields both road-mobile and silo-based ICBMs with MIRV configurations and is rapidly expanding its land-based ICBM silos as well as investing heavily in its seaborne nuclear deterrent.

As we have explained in the past:

“A MIRV configuration not only increases the total number of targets that a single missile can strike but also complicates things for enemy defenders by increasing the volume of threats they have to contend with. Modern ICBMs typically carry decoys (also known as penetration aids) and have other countermeasures to make detection, discrimination, and any attempted intercepts of the missile and/or the re-entry vehicles it releases even more complex.”

While multiple warheads were a threat that the original Mozyr system would have had to contend with, since then, there have been more developments in terms of penetration aids, which comprise decoys and other devices intended to make it difficult for enemy forces to determine which of the incoming objects are real threats, track them, and potentially attempt to intercept them. Even without penaids, the prevalence of MIRVs makes the job of a system like Mozyr that much harder, with the possibility of it being overwhelmed with warhead targets.

The U.S. Air Force video below gives a good general look at how the payload bus on a typical MIRVed ICBM, loaded with a mixture of warheads and penetration, functions.

A modern-day APS for ICBM silos would not only face more challenges in terms of advanced decoys and other countermeasures, but also from fast-moving and increasingly maneuverable warheads, including unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicles.

Nevertheless, the original Cold War concept remains an interesting one. At the very least, if perfected, it would seem to provide a far less costly alternative to the missile-based ABM systems that are otherwise the focus of these efforts in China, Russia, and the United States.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com