Just weeks after Russian President Vladimir Putin mentioned it in a provocative speech, Russia has reportedly decided to shelve development of its RS-26 Rubezh intercontinental ballistic (ICBM) missile system and focus on fielding the nuclear-armed Avangard hypersonic boost glide vehicle using other designs. The decision suggests the Kremlin may feel the hypersonic weapon is more valuable than the missile carrying it, but also raises questions about whether the country has the necessary funds to support its broader strategic plans.

On March 22, 2018, Russian state-run news outlet TASS reported that development of the RS-26 was no longer a feature of the state armament plan for 2018 to 2027. In an annual state of the union address on March 1, 2018, Putin said that the road-mobile Rubezh would be the primary launch vehicle for Avangard. The country had previously used the latter name to refer to the entire development program, including the intercontinental ballistic missile component.

“The Avangard was included in the [state armament plan] program’s final version as more essential to ensure the country’s defense capability,” the source said, according to TASS. “All the work on the Rubezh and the Barguzin [rail-mobile ICBM] was put on hold until the end of 2027. A decision on the work’s resumption will be made after the current armament program is fulfilled.”

Reportedly a smaller derivative on the RS-24 Yars ICBM, the RS-26 has been in development since before 2011. It is a controversial design that some have suggested could actually violate the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, commonly known as INF. Though Russia has insisted it is an ICBM, and has demonstrated that it can reach the appropriate range, experts believe this was only because the missile involved in the launch in question was carrying a light payload or no payload at all.

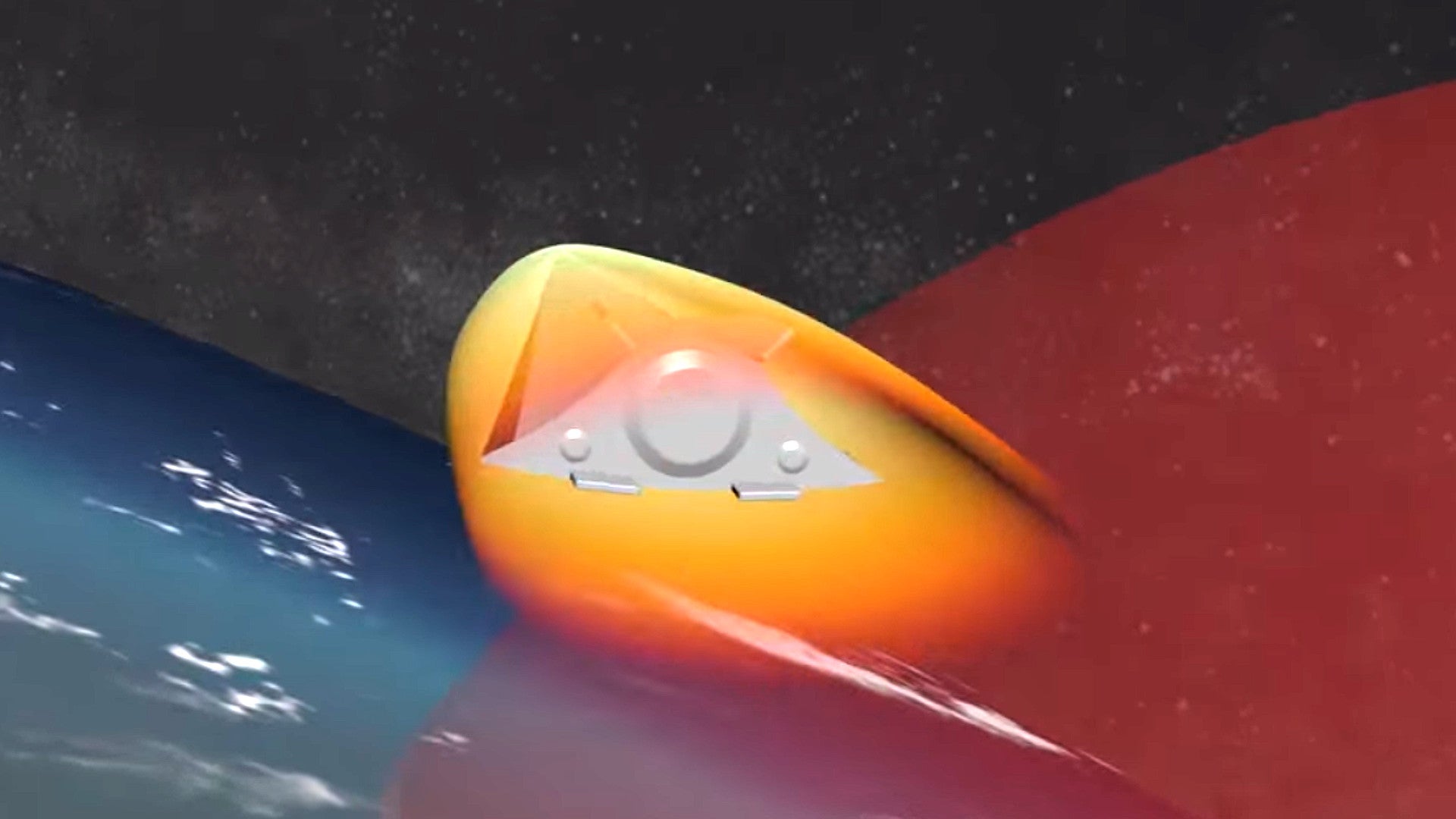

The Russian Ministry of Defense released the video below earlier in March 2018 reportedly showing Avangard prototypes and a computer generated depiction of its operational concept.

Subsequent tests have strongly indicated the missile can’t fly beyond intermediate ranges with an actual warhead, making it a design that the INF would prohibit Russia from fielding operationally. The United States accuses Russia of having already put a treaty-breaking ground-launched cruise missile, the SSC-8, into service and the RS-26 appeared to be another means of skirting the agreement’s restrictions.

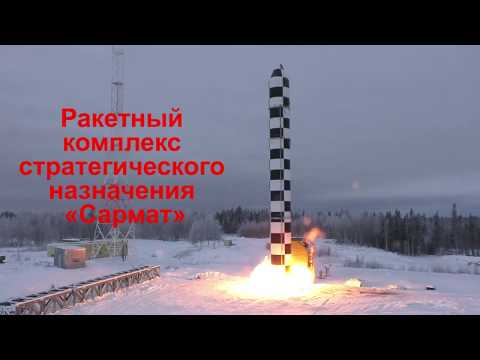

Without the Rubezh, the primary launch vehicle for Avangard will likely be the still-in-development silo-launched RS-28 Sarmat ICBM, also known as the “Satan 2.” This missile is set to replace the older R-36M, also called the SS-18 Satan, by 2020. Some reports suggest it may be able to carry as many two dozen of the hypersonic boost glide vehicles, but this remains unconfirmed.

The video below shows tests of the RS-28 Sarmat ICBM.

However, separate TASS reports say that the hypersonic boost glide vehicle will be operational by 2019 and that it could enter service first aboard older UR-100N UTTKh IBCMs, also known as the SS-19 Stiletto. Russia reportedly acquired approximately 30 more of these Soviet-era weapons, in a deactivated state, from Ukraine in the early 2000s, and would refurbish and modify them in order to carry Avangard.

Since these weapons remain in Russian service already, it would be relatively easy for the country to swap out the existing weapons with upgraded versions carrying hypersonic vehicles. Per the terms of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) that Russia is party to with the United States, both countries can only have so many “launchers,” which includes land-based silos, mobile launch vehicles, or individual launch tubes on submarines, as well as nuclear-capable bombers. However, the deal sets higher limits on the total number of warheads either side can retain in total and places no restrictions on how many missiles without warheads a country can have in storage.

This plan makes a lot of practical sense. As we at The War Zone have written in detail before, the benefit of a hypersonic boost glide vehicle is that it eliminates many of the existing vulnerabilities of traditional ICBMs, which follow largely predictable signatures and flight paths after launch.

While existing U.S. space-based early warning sensors should be able to detect the launch of any one of the Russian ICBMs, especially from the thermal plume of the missile blasting off, they wouldn’t be able to monitor the subsequent flight of Avangard, which will reportedly be able to make rapid and frequent course changes at extremely high speeds. By the Pentagon’s own admission, the new component of the U.S. military’s ballistic missile shield wouldn’t be able to shoot down such a weapon, either.

“Our defense is our deterrent capability,” U.S. Air Force Gen. John Hyten, head of U.S. Strategic Command, told members of Congress during a public hearing on March 21, 2018. “We don’t have any defense that could deny the employment of such a [hypersonic] weapon against us, so our response would be our deterrent force which would be the triad and the nuclear capabilities that we have to respond to such a threat.”

In February 2018, Hyten detailed the need for faster development of new space-based sensors that would be able to pick up hypersonic threats, but that capability is still likely some years away. Russia, which routinely criticizes any and all American ballistic missile defense efforts, is undoubtedly aware of this, which helps explain the focus on Avangard.

As it stands now, there is no realistic means of destroying a ballistic missile the Russians would launch from within their own territory during its vulnerable boost phase. Coupled with the sensor- and countermeasure-dodging capabilities of the hypersonic vehicle itself, the launch platform’s job is largely reduced to just getting that system to the right altitude and speed.

The decision to abandon to the RS-26 in favor of putting Avangard on other platforms could also point to the hypersonic boost glide vehicle being further ahead in development than we might have previously understood. If that’s true, it’s also possible the Russians might also be inclined to look into retrofitting other existing ICBMs, such as the road mobile RT-2PM2 Topol-M and RS-24 Yars, with the new warhead.

It’s worth noting, of course, that the U.S. ballistic missile defense shield as it exists today is in no way capable of defeating the Kremlin’s existing nuclear deterrent capabilities, either. This then brings up the possibility that the Russians simply can’t afford RS-26, whether they want it or not, along with the slew of other advanced strategic capabilities they claim to be pursuing.

“It was initially planned to include both the Avangard and the Rubezh in the state armament plan,” the anonymous defense industry source told TASS. “It became clear later that funds would not suffice to finance both systems at a time.”

There’s evidence that this may have been increasingly apparent for some time. Prior to Putin’s remarks in March 2018, there had been scant official mention of the RS-26 at all for years. The Kremlin was supposed to demonstrate the system to arms control inspectors from the United States first in 2015 and then in 2016, an event that still has not come to pass.

Digging the old UR-100Ns out of storage can be seen as a cost saving measure as much as it is a way to potentially get Avangard into service faster, too. It’s an established design that Russia already knows how to operate and maintain.

And despite Putin’s fiery remarks about the West having failed to contain his country, there are indications that international sanctions in response to Russia’s illegal annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014 and subsequent involvement in that country’s still-simmering civil conflict are having an impact. In March 2017, the Russian Federal Treasury announced deep cuts to defense spending, which subsequently forced the country to put a host of large-scale projects, including the Barguzin rail-mobile ICBM, on hold indefinitely.

Earlier in March 2018, President Aide Andrei Belousov announced plans to trim billions of dollars more from upcoming defense budgets, though he claimed it was because of reduced demands from Russia’s armed forces. “This will be simply because we have passed the peak of saturating our defense forces with new types of armaments and military equipment,” he said.

True or not, there are still serious questions about whether or not Russia will be able to sustain its myriad of strategic weapons programs in the future. At present, the country claims to be working on the RS-28 ICBM, Avangard, the Kinzhal air-launched hypersonic nuclear missile, a fleet of upgraded Tu-160M2 long-range bombers, the Poseidon long-range nuclear torpedo, the Burevestnik nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed cruise missile, as well as upgrades to many of its existing designs, including the addition of advanced warheads.

And while it might still be cheaper than an all-new missile, it could easily cost a significant amount of money to rehabilitate the UR-100N ICBMs and make them compatible with the hypersonic boost glide vehicle. There are reports that adding Avangard would make the missile substantially longer, too, which would necessitate the modification of the existing silos or the construction of new ones.

Still, with all of these systems in various stages of development or production, it’s easy to see how the Kremlin could have decided it didn’t need the RS-26, too. But with the almost certainly high costs associated with this broad strategic armament program, the Russian government might not have had a choice when it came to deciding whether to keep working on this missile system, and it might be forced to curb its ambitions further into the future.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com