A recently released document shows the U.S. Air Force assessed various alternatives to fielding its future LGM-35A Sentinel nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, as well as the possibility of deploying any such future weapon outside of traditional silos, including multiple concepts previously explored decades ago. Buying a land-based version of the U.S. Navy’s Trident II submarine-launched ballistic missile, a new smaller missile with intercontinental range, or a design based at least in part on an existing commercial space launch rocket, as well as basing them in tunnels or at the bottom of deep lakes were all concepts that were examined.

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) think tank was among the first to spot the new details about the Air Force’s ICBM-replacement decision-making processes in a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) regarding the future deployment of the LGM-35A and the decommissioning and disposal of the service’s existing arsenal of LGM-30G Minuteman IIIs that was released on July 1. Many of the concepts described within evoke memories of proposed ideas from the last time the Air Force worked to acquire a new ICBM in the 1970s and 1980s. Those past initiatives ultimately resulted in the acquisition of the silo-based LGM-118A Peacekeeper, the last of which were removed from the Air Force’s inventory in 2005 as a result of arms control agreements between the United States and Russia.

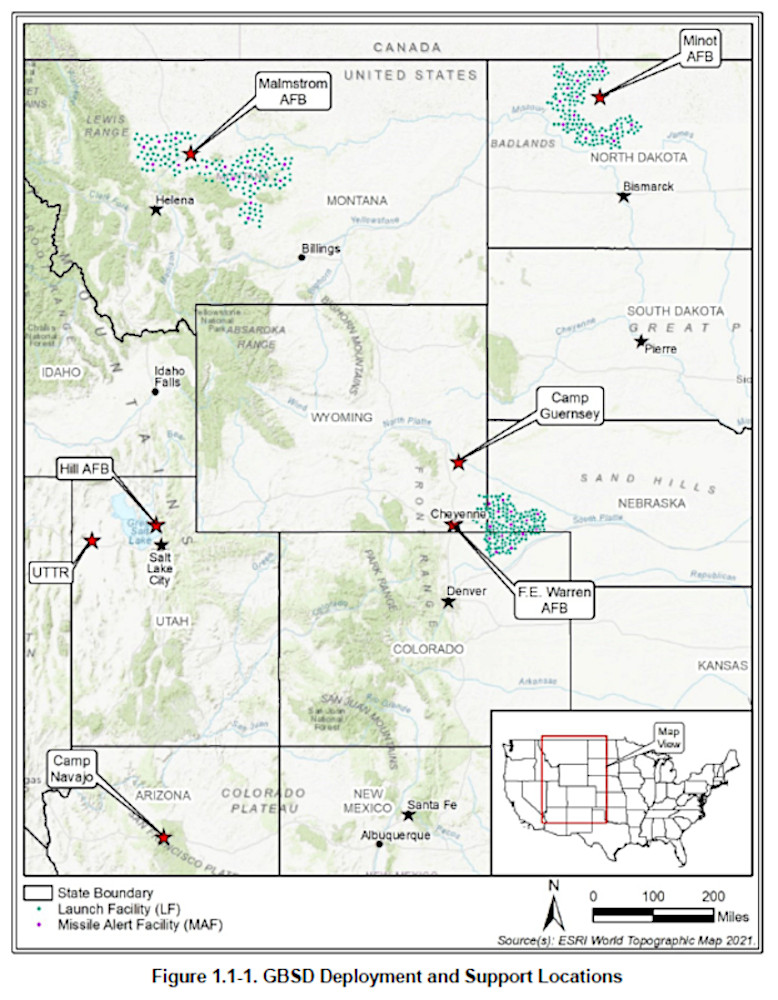

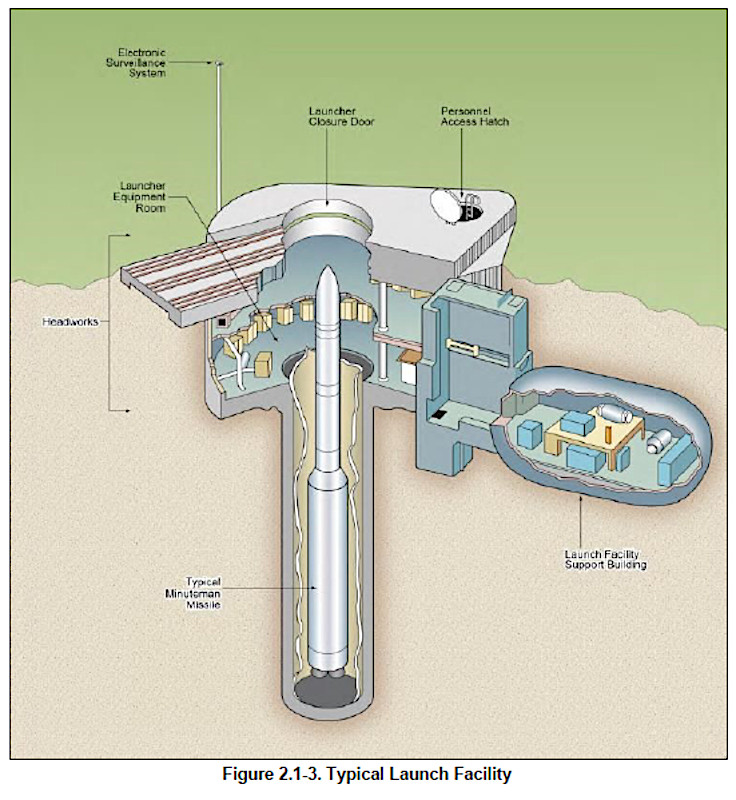

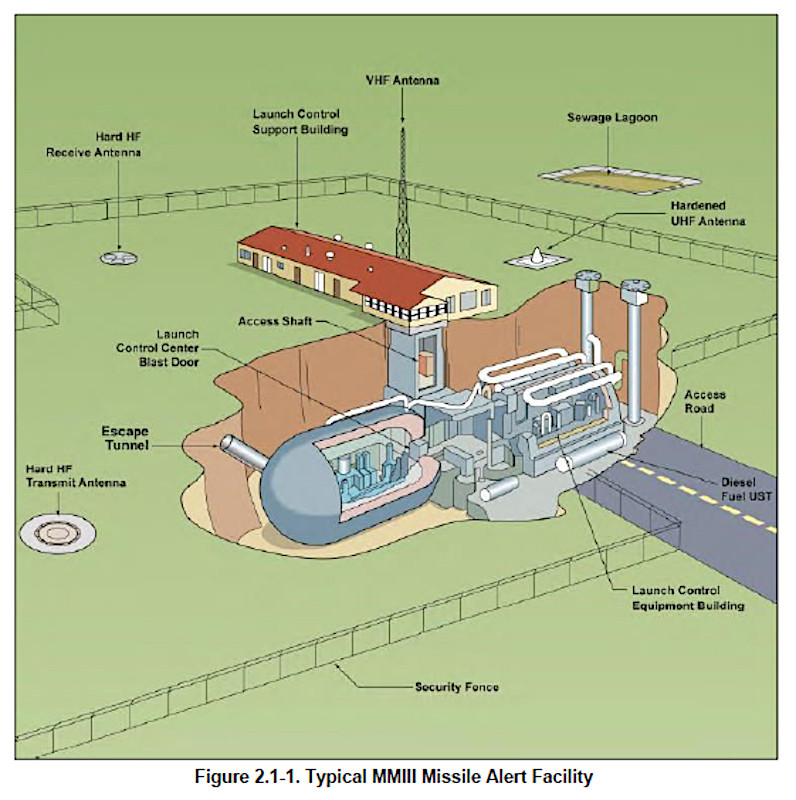

The Air Force formally selected a team led by Northrop Grumman as the winner of its Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program in 2020, with Boeing having dropped out of the running the year before. In April, the service announced that the new missiles, which are set to replace the 400 LGM-30Gs on a one-for-one basis, would be designated LGM-35A Sentinels. ICBM silos and associated command and control facilities spread across five states, as well as other related infrastructure, is also set to be modernized as part of the fielding of the new LGM-35As. The estimated total cost to acquire the missiles and upgrade the relevant facilities has been pegged publicly at around $100 billion. The cost estimate for the entire program, to include operations and maintenance costs into the 2070s when these weapons are expected to reach the end of their service lives, has been set at $264 billion in the past.

The Air Force has aggressively defended its decision to pursue a new ICBM for years now, but the EIS provides some of the most substantive information to date on how it chose the course of action that it did and what alternatives it explored first. The document says that the service considered four alternatives to the idea of the new GBSD missile and two alternatives to integrating whatever missile it did choose into the existing Minuteman III basing infrastructure.

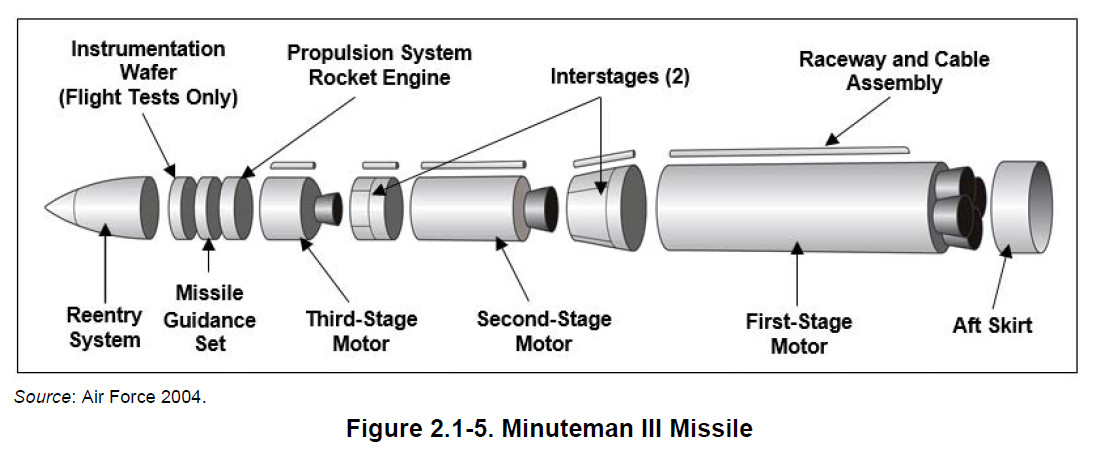

The first possible alternative missile option, and the one that U.S. officials have discussed and dismissed most publicly, was the idea of an extensive rebuild of the LGM-30Gs. “During the reproduction process, first- and second-stage rocket boosters would be washed out and refilled with new solid-fuel components, and the third stage would be remanufactured. PSREs [propulsion system rocket engine] would also be remanufactured (build-to-print), and all other subsystems would be refurbished and replaced,” according to the EIS.

The EIS says that the Air Force rejected this proposal because the rebuilt missiles would not meet new survivability and other performance requirements, would still not be sustainable in the long run, and would not readily integrate with already planned infrastructure improvements. The service has long argued that utilizing Minuteman IIIs in any fashion is not a reasonable alternative to a new ICBM.

Matt Korda, a Senior Research Associate at FAS and manager within its Nuclear Information Project, wrote in a blog post yesterday that this logic seems somewhat curious given that the Minuteman III will continue to be the Air Force’s only ICBM for years to come until the initial batch of LGM-35As goes on alert. “It is highly significant to state that the Minuteman III cannot meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs, given that the Minuteman III currently performs the ICBM role for the US Air Force and will continue to do so for the next decade,” he explained.

The Air Force passed on the possibility of acquiring a land-based version of the Navy’s Trident II missile, which is also known as the D5, for many of the same reasons. In addition, the service said that deploying those weapons would be “cost prohibitive” because of associated infrastructure improvement requirements due to the projected weight of the missiles. Though it’s not clear how heavy the new LGM-35A will be in the end, the Trident II in its submarine-launched configuration tips the scales at approximately 130,000 pounds, more than 50,000 pounds heavier than the LGM-30G.

The Air Force also raised largely unexplained reliability and safety concerns about a Trident II derivative, despite the design being well-established and demonstrably reliable. Just last month, the Navy test-fired four unarmed improved D5 Life Extension (D5LE) missiles without incident.

“The Air Force’s concerns over road and bridge quality are probably justified––missiles are incredibly heavy, and America’s bridges are falling apart at a terrifying rate,” FAS’s Korda wrote. “However, it is unclear why the Air Force is not confident about the D5’s motor performance, given that even aging Trident SLBMs have performed very well in recent flight tests.”

Beyond existing missiles, the Air Force looked into fielding “a reduced-size missile with lower procurement costs and enhanced accuracy” and the idea of “using commercially available or newly designed commercial launch vehicles and platforms that would meet the operational envelopes of the land-based ICBM program.”

The idea of what might be described as a miniature ICBM is not new to the Air Force. In the 1980s, the service conducted significant development work on a road-mobile Small Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, which was subsequently designated the MGM-134A Midgetman. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of the Cold War led to the cancellation of that program, though advanced solid fuel rocket motor technology developed for the Midgetman found a second life in commercial space launch rocket designs.

With regards to the commercial avenue, the EIS does not say whether the Air Force considered any specific existing launch vehicle design as the possible basis for a new ICBM. It’s worth noting that most well-established space launch rockets available in the U.S. now, like the United Launch Alliance’s Delta series or SpaceX’s Falcon family, are liquid-fueled, at least in part.

Rockets that use solid fuel motors are, by and large, safe to handle and easier to fire than liquid-fueled types, given the volatile and corrosive nature of the latter types of propellants. Historically, liquid-fueled ballistic missiles, including ICBMs, have been designed to be fueled right before launch, increasing the time necessary between the recipe of a launch order and the missile actually blasting off. However, more stable liquid fuel concepts do exist and continue to be utilized in ballistic missile designs today, notably by Russia and North Korea.

More advanced solid fuel rocket motors are used in the commercial space launch industry, as well. Some members of the Delta series of space launch rockets notably utilize solid fuel boosters that were developed in part using technology taken from the Midgetman project.

Regardless, the EIS says that the Air Force passed on what might’ve become a ‘Midgetman 2.0’ and a commercial derivative design because they would not meet desired survivability and performance requirements and would “introduce programmatic or functional risk during the design and development of the missile.” With regards to the smaller missile option specifically, the service also pointed to the fact that such a weapon would not be able to be readily deployed within the existing Minuteman III launch architecture.

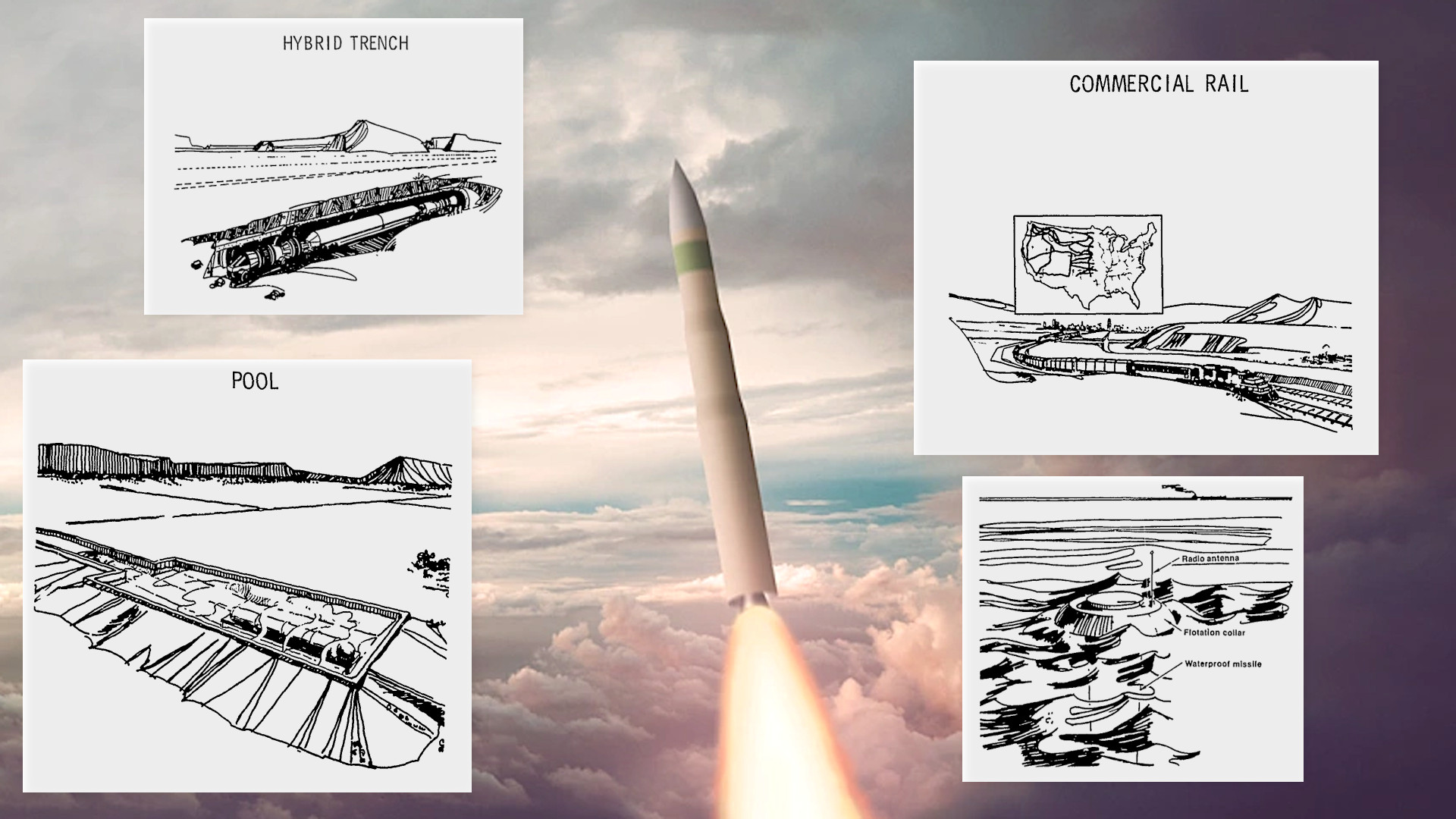

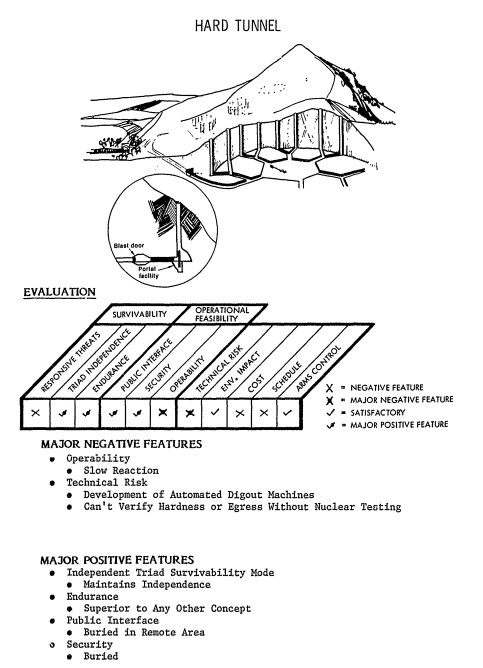

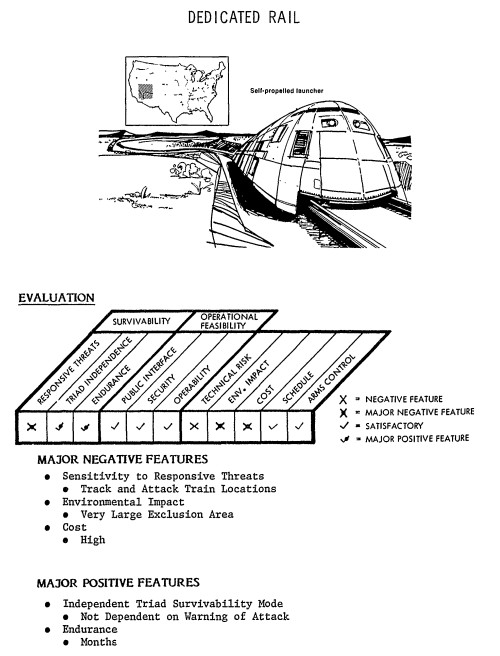

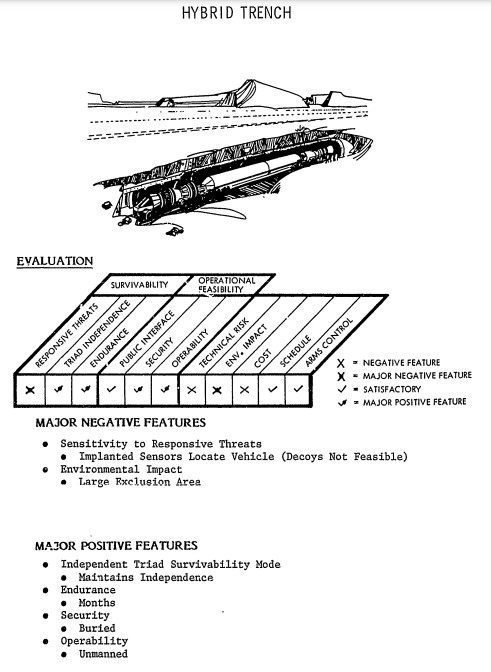

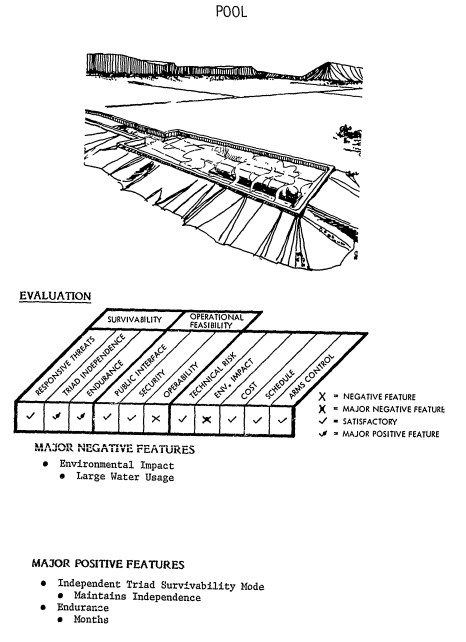

Beyond missile alternatives, the Air Force considered getting away from traditional silos entirely. Tunnel networks and launch systems tethered to the bottom of very deep lakes were analyzed as options for firing existing Minuteman IIIs, refurbished examples of those missiles, or a new design. What’s particularly interesting here is that both of these basing operations were considered as part of the MX ICBM program in the 1970s and 1980s that eventually produced the LGM-118A.

The proposed “underground tunnel system to shuttle ICBMs, predominantly by rail, among an array of underground silos and storage bunkers” that the Air Force looked into “would include locating, designing, excavating, developing, and installing critical support infrastructure such as rail systems and LFs [launch facilities] for an array of underground tunnels that would likely span hundreds of miles,” according to the EIS. “This alternative would provide enhanced survivability through ‘location uncertainty’ by using an undiscernible network of underground rail systems in secured public lands.”

This is extremely similar to various ‘shell game’ basing concepts that were very actively considered for MX. The central idea in each of those proposals was the same kind of “location uncertainty” described in the EIS. This, in turn, would make it harder for an enemy to target the missiles and force them to commit a larger number of their own nuclear weapons to ensure the total destruction of America’s ICBMs during a nuclear exchange. You can read more about that here.

The EIS says the Air Force rejected this idea this time around for more or less the same reasons it abandoned tunnel networks and other similar basing concepts for MX in the latter decades of the Cold War. Constructing this new infrastructure would be extremely costly and would present “extreme or unsurmountable environmental consequences,” according to the EIS.

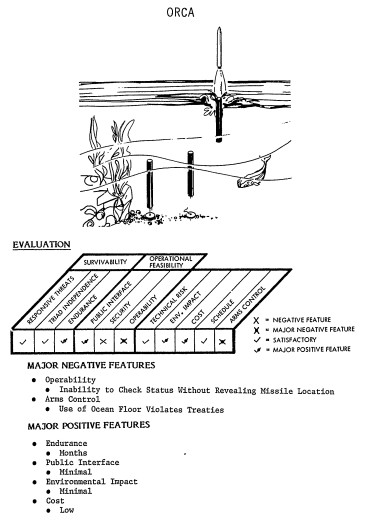

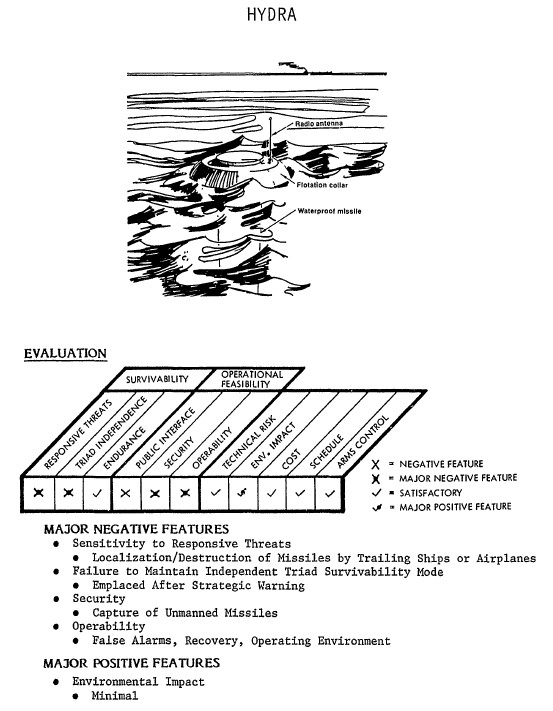

The Air Force’s idea to “place floating silos in deep-water lakes using tether assemblies,” which would “include locating, designing, developing, and installing critical support infrastructure such as water-based transportation systems and an array of floating or underwater LFs” leveraging “technology used for launches from ships or submarines,” is similar to other proposed MX basing concepts. The main benefit behind the different underwater and pool/lake type basing options for MX was also increased survivability, with the potential again to present a shell game-like dilemma for opponents that would prevent them from being absolutely sure that they were targeting an actual U.S. ICBM.

Again, the Air Force concluded this was a no-go due to cost and environmental factors. In addition, the service assessed that this basing concept “would not appreciably reduce an adversary’s cost to attack” and would “not meet the Air Force’s security standards.”

It is, of course, worth noting that the EIS contains unclassified summaries of the Air Force’s assessments of these alternative missile and basing options, and does not provide details about exact technical issues or cost comparisons. Interestingly, the document says that the service, having found all of these alternatives unacceptable for various reasons, decided to pursue a new full-size ICBM after conducting a final analysis of that course of action over the only other remaining option: taking no new action.

Furthermore, the EIS says that an unspecified “interested party” said that those two options should have been considered against the possibility of reducing the Minuteman III arsenal or eliminating it entirely. “While the commenter expressly offered elimination of all nuclear weapons as an alternative that should be considered, their argument includes a statement that the MMIII [Minuteman III] inventory was previously decreased and could be again, implying reduction of the inventory was another alternative that should be considered,” the document says.

The Air Force said it could not even consider this because of legal requirements from Congress to “accelerate the development, procurement, and fielding of the ground-based strategic deterrent program.” However, this is something that has come up for discussion within that legislative body, as well as from senior leaders in the U.S. military and the American public. U.S. officials make no secret of the fact that today the ICBM force exists in large part to serve as a “sponge” to soak up incoming warheads during a potential nuclear exchange with an adversary like Russia or China. The War Zone has explored the potential cost and other benefits of dispensing with the ICBM leg of American nuclear triad in depth on multiple occasions.

As it stands now, there is no indication that President Joe Biden’s administration or the current Congress are in any way considering scaling back or canceling purchases of LGM-35A Sentinels. The Air Force is expecting to reach an initial operational capability with these new ICBMs in the 2030s.

Whatever the future might now hold for America’s ICBM force, we know it won’t include repurposed missiles, mini-ICBMs, or weaponized space launch rockets rolling around underground on trains or hidden at the bottom of lakes.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com