The U.S. military is increasingly viewing the growing threats posed by kamikaze drones, especially longer-range types, and the need for more ways to defend against them, as evidence of an opportunity. The top U.S. Air Force officer in Europe has said that what are also now commonly called one-way attack drones could be a very useful lower-cost stand-off strike capability, particularly for smaller NATO members and other American allies and partners who might not be able to afford higher-end exquisite weapon systems. This could also be a critical avenue to help address growing concerns about the size of U.S. military stockpiles of stand-off munitions.

Air Force Gen. James Hecker talked about what kamikaze drones might offer to friendly forces, as well as the dangers they represent, yesterday during a virtual talk hosted by the Air & Space Forces Association’s (AFA) Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. Hecker is the commander of U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), as well as head of Air Forces Africa (AFAFRICA) and NATO’s Allied Air Command. The war in Ukraine, which is right in Hecker’s operational backyard, as well as ongoing crises in and around the Red Sea and elsewhere in the Middle East, have fully thrust drone threats into the mainstream consciousness.

“Different than [during] the Cold War is the precision of the munitions that we now face from the adversary, and the quantity of precision munitions,” Hecker explained. “We were just talking about cruise missiles about two and a half years ago, and they are pretty expensive, so a country couldn’t buy a lot of these things. But what we see now are 10-20,000-dollar one-way UAVs [uncrewed aerial vehicles] produced, obviously cheaply, and produced in mass and at scale.”

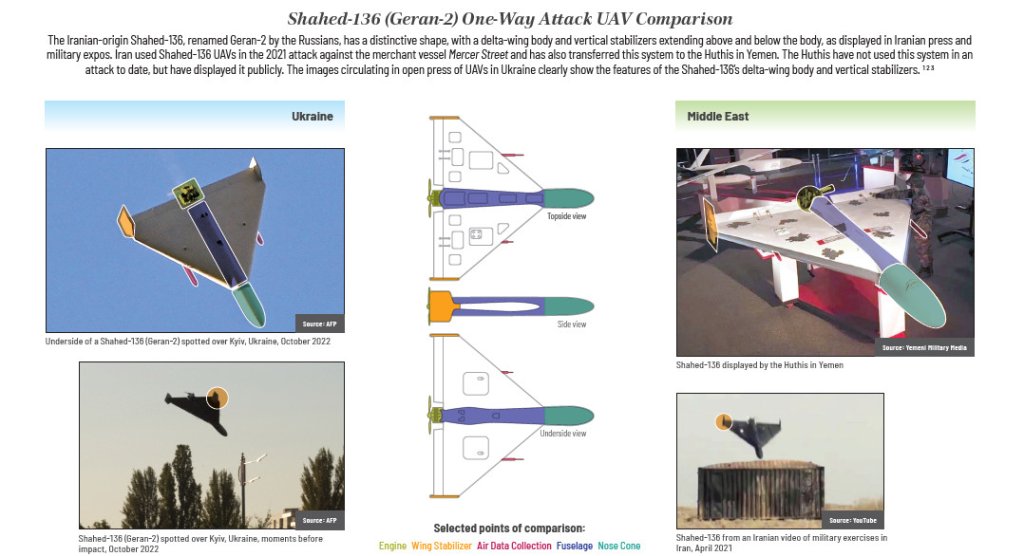

It’s worth noting here that estimates of the true unit price of an Iranian-designed Shahed 136, the primary example today of a kamikaze drone with cruise missile-like range, are between $50,000 to $150,000. Shahed 136s, as well as its predecessor the Shahed 131, and derivatives thereof, are in widespread use by Russia against targets in Ukraine and by Iran and its proxies across the Middle East. However, $100,000 is still relatively low-cost compared to traditional cruise missiles and many other precision air- and surface-launched munitions, which can easily be exponentially more expensive. The U.S. military also still very much views cruise missiles, which continue to proliferate, including to non-state actors, as a serious threat.

“And they’re [kamikaze drones] quite capable, as well. They know how to play with altitude, they know how to avoid sensors, and they have a pretty good package to get them to the target that they’re anticipating get[ting] to,” he continued. “So, you know, the problem got complicated here in the last two and a half years, and the proliferation… every country, you know, can afford these kinds of things and we have to go against them.”

Hecker did not elaborate on the capabilities he described or how widespread the use of kamikaze drones with those guidance packages might be. The Russians have clearly been working to improve the guidance and other capabilities of the core Shahed 136 design. The war in Ukraine has also become a battlefield incubator for the rapid iterative development of other kinds of kamikaze drones, especially highly maneuverable, but relatively short-range first-person view (FPV) types.

Hecker did say that getting after these threats would require novel approaches, highlighting Ukraine’s ad-hoc acoustic sensor network as he has done now multiple times. The network makes use of thousands of cellphones and microphones mounted on poles to help detect incoming drone attacks and alert drone-hunting teams on the ground primarily armed with machine guns mounted on trucks, as you can read more about here.

“Here’s what we can’t do. We can’t go against them with a Patriot [surface-to-air missile]. … We can’t go against them with a $1 million hammer,” Hecker said. “That is on the wrong side of the cost curve when it comes to those things.”

What Hecker said makes him view this concerning reality as an “opportunity,” as well as one of “the things that keep me up at night,” is that this calculus goes both ways. “We can use them [as] well and put adversaries on the wrong side of the cost curve”

“What we’ve seen with Ukraine and Russia [is] that there’s a lot of cheap systems that enable the exquisite and we have countries here in NATO that would be happy to build those… because they can’t afford the exquisite stuff,” the Air Force’s number one officer in Europe continued. “And that can be complementary to the exquisite and, sometimes, it can actually do the mission by itself.”

Western defense contractors, including in Europe, are already increasingly offering lower-tier one-way attack drones, as well as loitering munitions with additional capabilities, in part in response to contracting opportunities to supply Ukraine. NATO members, such as Poland, which can also afford more exquisite capabilities, are themselves starting to acquire those capabilities in greater numbers, as well.

Interest in more Shahed-like kamikaze drones is growing in the West and there are already options available on the open market, especially from firms in Israel who have been and continue to be pioneers in this field. Iran’s Shahed 131/136s and their derivatives are heavily influenced by, if not directly derived from the first-generation Israeli delta-winged IAI Harpy loitering munition. Harpy and its successors in Israel have also at least inspired designs developed elsewhere.

“And then you throw in the high-low mix, where now I can take 15 countries that really couldn’t afford and couldn’t help a whole lot within NATO with exquisite stuff, now they can purchase one-way UAVs that can make the exquisite better or sometimes even do the mission,” Hecker added.

The value proposition that kamikaze drones present is not only limited to countries with smaller defense budgets, either. There are already a growing number of efforts to field various tiers of air and surface-launched loitering munitions across the U.S. military. At least one loitering munition, the Switchblade 600, was among the first batch of systems designated to receive special attention through the Pentagon’s Replicator initiative. The Replicator’s main goal is to help the branches of the U.S. armed forces field thousands of uncrewed systems with autonomous capabilities in 2025. It also reflects a larger push for a culture change across the Department of Defense when it comes to thinking about uncrewed systems, especially lower-cost ones.

On top of this, the line between longer-range kamikaze drones like the Shahed 136 and traditional cruise missiles is increasingly blurry. The U.S. Air Force, as well as the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, have been actively working to develop and field new lower-cost stand-off munitions that may ultimately end up somewhere in between design-wise. As a prime example of this, there has been debate over the appropriate classification of the so-called Enterprise Test Vehicles (ETV) now being developed under a program the Air Force is running together with the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU).

“People… were thinking about how we do a better job of applying digital engineering and said you know, ‘if we built a software programmable, modular, but recoverable air vehicle that looks a lot like a missile and flies over most of the missile envelope that could greatly accelerate how we do test[ing],” Tim Grayson, Special Assistant to Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall, said during a separate talk AFA’s Mitchell Institute hosted today. “And it was sort of like chocolate and peanut butter coming together. …this modular thing for testing purposes, it’s very adaptable, one of the modules is a warhead, sure looks like a low-cost cruise missile.”

Grayson said this particular chain of events led to a concept now called the Affordable Mass Munition, which also sounds very much in line with the thinking behind the ETV effort. It also reflects larger trends within his service.

“A way of thinking that I think is increasingly taking hold across the Department of Defense, and certainly in the Department of Air Force [is]… this idea of cost-effective mass,” Undersecretary of the Air Force Melissa Dalton also said this week at a talk at the Brookings Institution think tank in Washington, D.C. “For the Department of the Air Force, in particular, historically, we’ve focused on building a discrete set of exquisite platforms with an emphasis on quality, less on quantity. But quantity can have a quality of its own when you’re thinking about how to be able to penetrate through or to be able to disrupt the type of contested environments that certainly we would find ourselves in, these types of scenarios.”

The scenarios Dalton was referring to include potential high-end conflicts like one in the Pacific against China. Wargames conducted under the auspices of the U.S. military and done independently have repeatedly produced evidence that swarms of relatively cheap networks of drones with high levels of autonomy could be a deciding factor in the success or failure of a Chinese intervention against Taiwan. Those swarms would be capable of performing electronic warfare, intelligence and surveillance, and other missions in addition to kinetic strikes. The U.S. military is now openly pursuing a strategy to help defend the island centered around turning the Taiwan Strait into a “hellscape” for invading forces full of marauding uncrewed systems in the air and down below. The Taiwanese armed forces have been working to acquire large stocks of kamikaze drones in line with these plans.

Gen. Hecker’s further highlighting of how kamikaze drones are one avenue to get on the right side of the cost curve also comes amid deepening concerns that America’s existing munitions stockpiles will not be able to meet future, if not current operational demands. On top of that, there are fears that existing supply chains and industrial bases are insufficient to help rectify those issues economically and in useful timeframes. New production concepts and expanding the number of available suppliers and producers are key components of the aforementioned ETV program. There is also a question in all of this about why the U.S. military does not just invest in its own Shahed-like design.

“The U.S. defense industrial base (DIB) is unable to meet the equipment, technology, and munitions needs of the United States and its allies and partners,” a report released just this week by the congressionally-manded Commission on the National Defense Strategy also declared. “A protracted conflict, especially in multiple theaters, would require much greater capacity to produce, maintain, and replenish weapons and munitions.”

“We don’t have enough topline money for munitions, full stop. … We [also] don’t necessarily have the weapons that we want right now,” Special Assistant to Secretary of the Air Force also said today. “So we need capabilities that expand the types of weapons we have and the diversity of that weapon portfolio.”

For all the focus on the very real and still growing threats that kamikaze drones present, they are also emerging as a potentially critical way for the U.S. military and its allies and partners to meet new and future operational needs, and do so in a cost-effective manner.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com