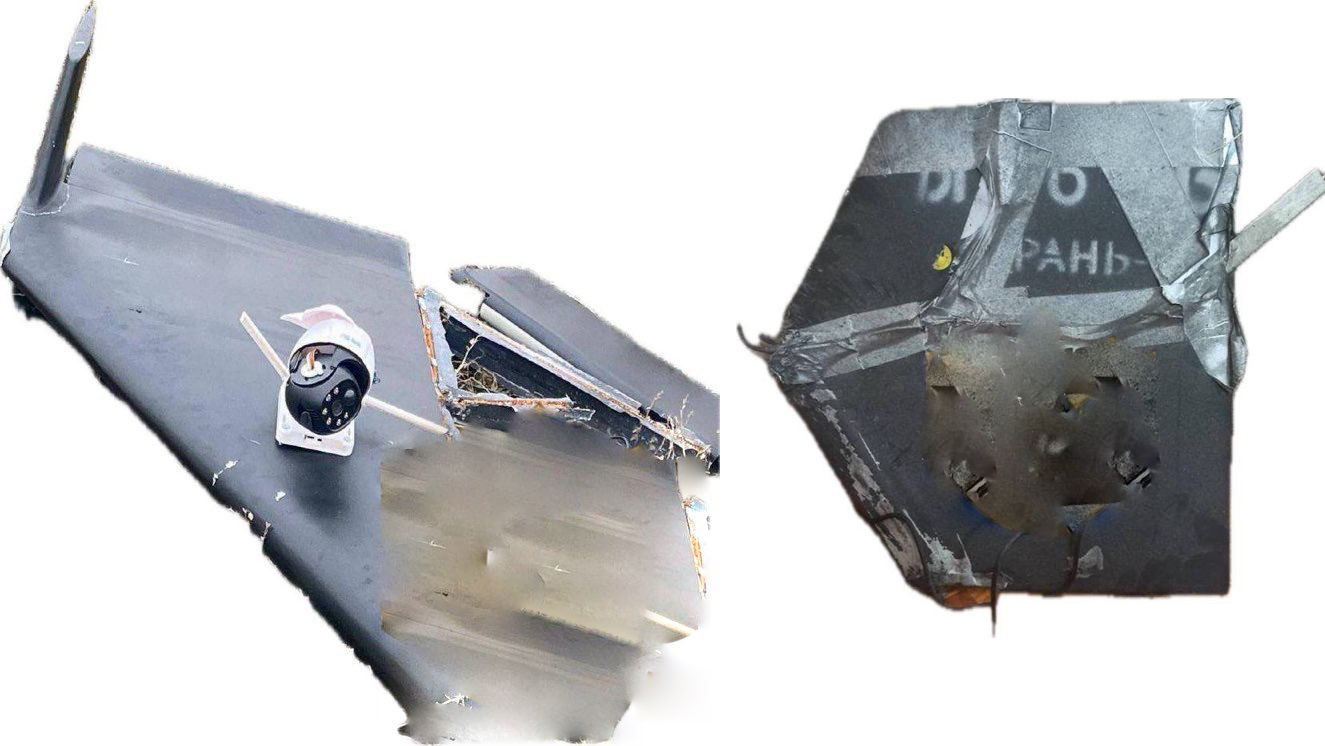

The latest Russian development involving the Iranian-designed Shahed long-range one-way attack drone reportedly comprises a pan/tilt video camera mounted on the UAV, allowing it to operate in a visual reconnaissance capacity. It is further claimed that the modified drone, seen in an image of a crashed example, uses Ukrainian wireless networks to transmit its imagery back to a control station. While this may look like a crude installation, it is potentially a solution to a very big problem Russia has faced since the beginning of the war and it could have major consequences for Ukraine, which we may already be seeing on the battlefield.

The Russian-operated Shahed is best known for its use in sustained standoff attacks on Ukraine, including against cities and civil infrastructure, in a large-scale bombardment campaign that has been ongoing since October 2022.

In the past, we have reported on the appearance of Shaheds fitted with 4G modems and SIM cards from Ukrainian telecom firms, the exact purpose of which was not immediately clear. The combination of a camera installed on the drone and the ability to use wireless networks, where available, would transform the Shahed into a relatively high-endurance, long-range visual reconnaissance asset capable of beyond-line-of-sight real-time operations, plugging what is otherwise a massive gap in the Russian arsenal.

At its most basic, a camera-equipped Shahed could fly to areas with assured cellular service and send real-time video reconnaissance back to Russian forces for exploitation. Unlike many other surveillance drones operated by Russia over the battlefield, it could also do this far behind the lines, taking advantage of the Shahed’s long reach. We detailed just such a potential application of the Shahed-136 here. Much closer to the front lines, it could also work within line-of-sight of a control station or a relay, the latter of which can connect the drone and receive its imagery, sending it to a control station much farther away.

At the same time, it’s worth remembering that adding cellular communications to a drone like the Shahed, or even a line-of-sight datalink, also risks giving away its presence and even its general position, making it more vulnerable to air defenses. The baseline Shahed-136 design doesn’t send out major radio-frequency emissions after launch, flying a pre-planned route to its target on autopilot. The use of active datalinks of any kind changes this low-signature profile.

The use of cellular data transmission, while very convenient, could also be a potential weakness that could be exploited in an attempt to shut down the use of these drones, via electronic warfare and cyber applications. This is something we have explored before.

Regardless, as we explored in the past, being able to dynamically control a Shahed-136 deep into enemy territory via a cellular data connection would dramatically change how these drones could be employed beyond what information they collect.

A reconnaissance-configured Shahed-136 could become a major problem for Ukraine. As noted earlier, Russia largely lacks this class of asset capable of beyond-line-of-sight connectivity. The workaround here is using cellular coverage opportunistically instead of high bandwidth satellite communications or a high-flying complex data relay/gateway platform. What we see on the crashed Shahed is a remarkably crude setup, with what appears to be an off-the-shelf camera system bolted directly onto the airframe. While this may look laughable, the simplicity has its advantages in terms of speed of modification and even production and overall cost. A Ukrainian military blogger commented: “Everything is done very primitively: glue, tape, cardboard, screws, wires, cheap routers and cameras. But it works.”

This configuration could still be highly experimental, as well, with very limited numbers being used to see how the concept works before investment into a more refined camera solution is made. Still, considering the attritable nature of the Shahed-136 in any configuration, using low-cost and preferably off-the-shelf parts as possible would make total sense.

Regardless of its homebuilt looks, the reconnaissance Shahed could provide real-time targeting, which would be taken advantage of using some of the new weapons Russia is pushing into the combat arena. Russia has used Iskander-M short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) to strike time-sensitive targets well behind enemy lines, as well. The long endurance of the Shahed would allow it to loiter over Ukrainian rear areas, or even very deep into the territory it controls, sending back imagery that could be used for rapid targeting by Iskander SRBM units and other standoff strike assets.

An Iskander-M strike on a pair of Patriot launchers roughly 20 miles from the front in Eastern Ukraine recently, seen in the tweet below, is an example of just this kind of operation.

Just today, a video was posted that also highlights the growing efficiency of Russia’s prosecution of time-sensitive targets well inside Ukrainian-controlled territory. In this case, a group of Ukrainian Mi-8/17 Hip helicopters came under attack, reportedly by rocket artillery and guided artillery ammunition, at a forward operating location. Once again, drones were used for targeting ahead of the engagement.

A reconnaissance Shahed could also follow strike versions of the same drones, or other weapons like cruise missiles, recording the effects of their attacks after they reach their targets. This would be especially useful for coordinating subsequent strikes. Just offering high-quality bomb damage assessment imagery would be valuable regardless of follow-on strikes. This could potentially be done without constant cellular connectivity, where it would take clips or images of preprogrammed targeted locations along a pre-programmed route that could upload them when a connection is established. While putting a Shahed-136 in such a high-risk mission would result in high attrition, the imagery gathered could save much more in terms of assessing if there is a need to send more weapons at the target or not. This is especially true for cruise and ballistic missiles that are very costly and time-consuming to procure.

There is also the possibility that the camera-toting Shahed is still fitted with its own warhead. This would allow it to strike targets of opportunity organically, without the need to call in another weapon, which takes time and can be very costly if that weapon is far more complex, like an Iskander-M. This would be a major leap in capability, allowing for attacking targets of opportunity literally anywhere in Ukraine where there is a steady cellular data connection.

Russia has already introduced various improvements and innovations to the Iranian-designed Shahed-136 drone, which is known in Russia as Geran-2 (Geranium-2).

Some of the enhancements that have occurred under Russian production include, reportedly, some type of radar-defeating materials or coatings, as well as a new composite structure that likely aids in mass production and could also help reduce the drone’s signature. Other changes include warheads packed with tungsten balls, instead of the original blast-fragmentation warheads. The drones are now wearing both light and dark color schemes, which are optimized for survivability in day and night operations separately.

Recently, we also got our first look inside the Russian factory where license production of the Shahed drone is taking place. The Russian production effort has been gradually switching from using Iranian-supplied subassemblies and is expected to make the full transition to Russian components sometime next year.

Meanwhile, Iran is making much larger upgrades to the Shahed-136 family, which includes integrated imaging seekers, a jet-powered type, and much more, that you can read about here.

Additional configurations of the Russian-made drones are bound to appear, with a strong possibility that more sophisticated camera installations could be among the changes, with the ultimate goal of allowing the Shahed-136 to hunt and kill on its own via some level of onboard AI-powered autonomy. But until that happens, Ukraine now appears to be dealing with the emergence of the threat of being hunted and killed via dynamic airborne targeting well beyond the front lines.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com