Russian forces in Ukraine appear to now be using so-called first-person view kamikaze drones controlled via a physical fiber optic line rather than a wireless data link. This configuration offers a control method that is immune to radiofrequency electronic warfare, but that also imposes certain limitations on how the system can be employed.

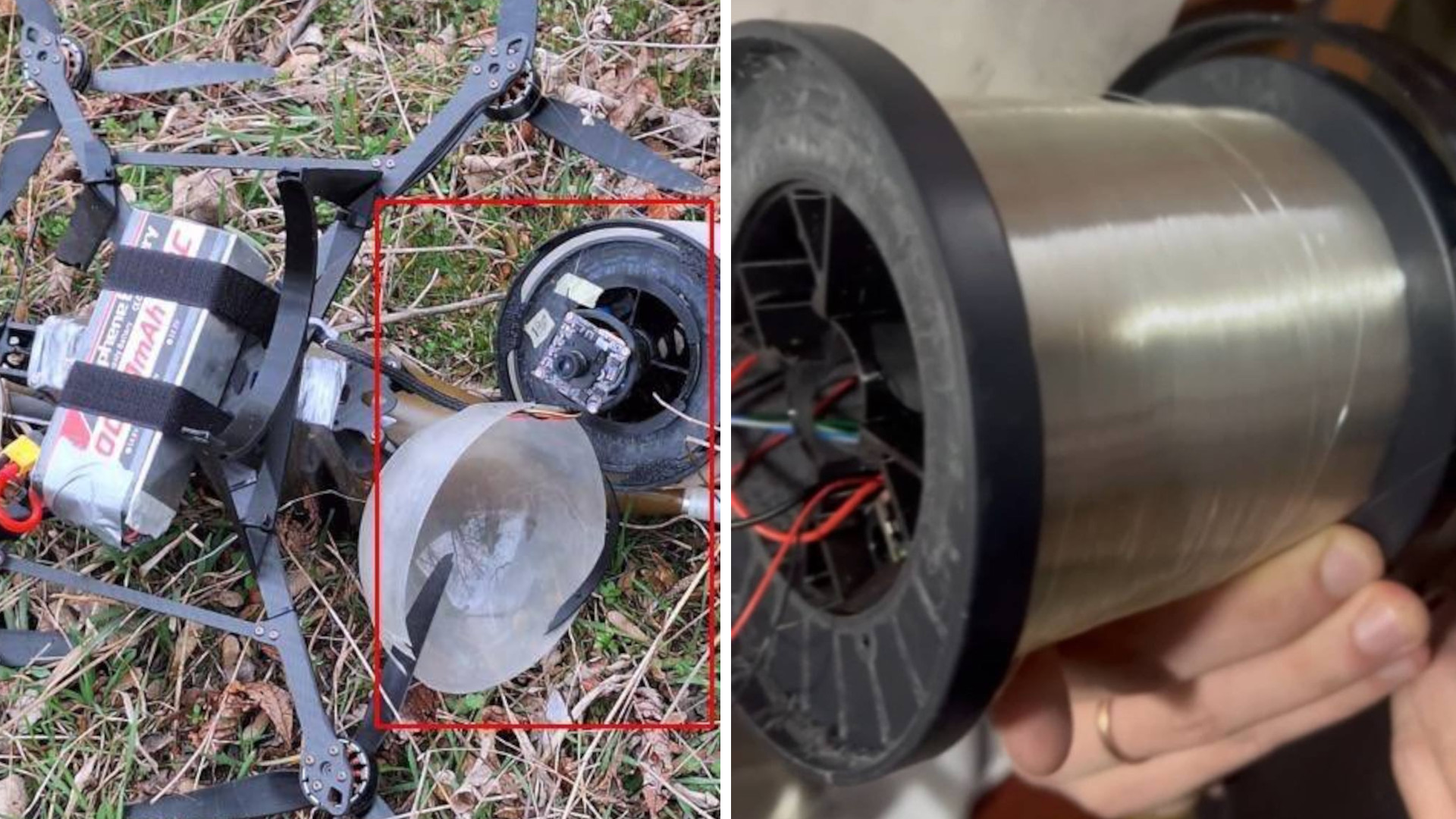

Serhii Flesh (also sometimes written Serhiy Flesh), a Ukrainian servicemember who has been cited as an expert in “radio technologies,” first posted pictures on the Telegram online messaging service of the apparent ‘wire-guided’ first-person view (FPV) drone yesterday. Where or when it was recovered is unclear. Flesh said he turned the drone over to the Birds of Magyar, a relatively well-known Ukrainian drone unit, for further analysis.

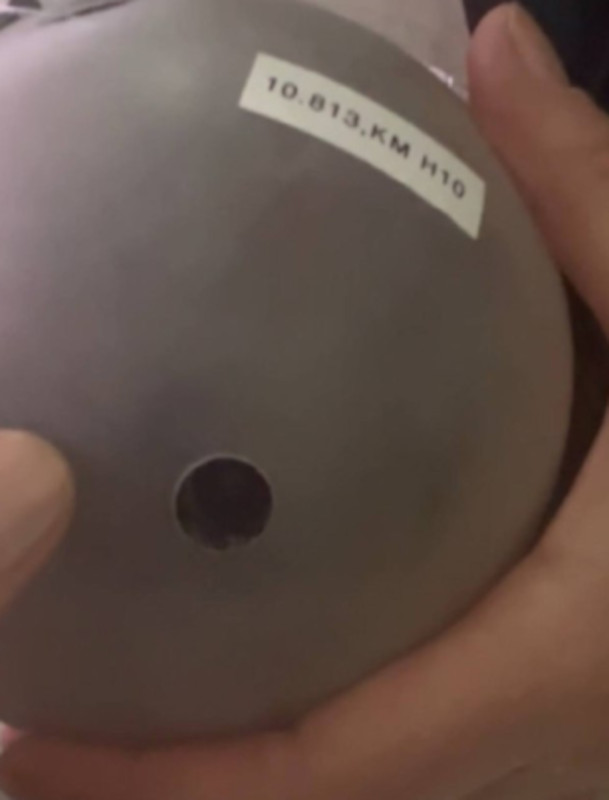

A picture Flesh shared showed a label on the spool of fiber optic line indicating that it, at least at one point, held nearly seven miles (just over 10.8 kilometers) worth of cable. One end of the line was linked to the drone’s main control section.

The drone otherwise has a general configuration that is commonly seen among FPV types operated by Russian and Ukrainian forces. It is a commercial-type quadcopter with a warhead that looks to have originally been intended to be fired from an RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenade launcher. FPV drones like this are designed to fly into a target and detonate.

FPV drones have proven to be incredibly effective on the battlefield in Ukraine, including against tanks and other armored vehicles. However, their control arrangement, which requires an operator to manually guide them via a wireless link, has always been a big advantage and something of a weak point. Russian and Ukrainian forces have been observed increasingly fielding various kinds of electronic warfare jammers, including ones mounted on vehicles, to help defeat these and other lower-tier drones using similar control arrangements.

The jammers do this by disrupting the datalink between the drone and the operator when in very close proximity to the vehicle. Oftentimes, this link already becomes degraded when the drone approaches its target due to the issues of maintaining line-of-sight radio connection between the drone and its operator as it gets very low to the ground. Terrain, man-made obstacles like buildings, foliage, and the curvature of the earth all work against maintaining this critical control pathway. The farther the controller is away and the higher or more complex the terrain is, the worse this problem becomes. So, using a fiber optic line that cannot be disrupted by these factors makes sense, even if as a backup system. You can read all about the line-of-sight issue and how it can be overcome, including by more autonomous drones infused with AI capabilities, in this past feature of ours.

This is not a new concept, broadly, either. Wire-guided anti-tank missiles have been in service around the world for decades now and many current-generation designs, such as some of Israel’s Spike family, use fiber optic cables. The ubiquitous American-made TOW missile has that feature directly in its name: Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided.

It’s also worth noting that many torpedoes also use a similar spooling wire command-link concept.

In his post on Telegram, Flesh also noted that the fiber optic line could allow for the operator at the other end to more quickly receive larger amounts of data, including a higher-quality video feed, from the drone.

Another major advantage to a wired FPV drone is that it would not radiate any energy, nor would the user some distance away, that could be detected. These electronic emissions are key ways drones are detected in the first place and they can also prove deadly for the operator if electronic surveillance systems can triangulate their position. There is no such vulnerability with a wire-guided FPV drone.

Using a wire-guided concept of operations for FPV drones could also help when it comes to the lack of certain components needed to build this class of weapon. Requiring no radio components may actually help in production when the components needed for that capability become scarce. This could also impact cost, although that should be relatively negligible.

Adding a physical tether to the drone could also present drawbacks. The effectiveness of FPV drones is due in large part to their high levels of maneuverability. A fiber optic line, especially one potentially stretching miles back to an operator, could easily get snagged on obstacles, wrapped up in its own rotors or around its body, and otherwise limit the drone’s ability to rapidly change course or slip into confined spaces. This is further underscored by the fact that wire-guided anti-tank missiles are typically employed with a relatively clear line of sight to the target. It could also limit the drone’s effective range, especially if elevated radio masts or other drones working as repeaters are used to extend line-of-sight connectivity. Recovering the drone if it is not used in a kinetic attack could also be much more problematic.

Wire-guided FPV drones would likely be most useful in established areas of control that are relatively open in terms of terrain, such as across a stabilized frontline area. Obstacles can be properly mapped and understood so as to avoid any major interaction with the wire, and so that distances to potential targets can be well defined. Using the weapons in shorter-ranged, nearly direct attacks or as near-distance loitering munitions is another good potential option. Also using tactics in which the drone maintains higher altitude before diving more directly down on its target, would also be an optimized profile for such a weapon.

If nothing else, the appearance of the apparent wire-guided FPV drone in Ukraine highlights how important these uncrewed systems have become in the fighting there. Both Ukraine and Russia are going all out to outbuild each other in terms of FPV drones, which officials have likened to now having an importance on the battlefield equivalent to artillery. With hundreds of thousands of these improvised weapons now being built each year, such innovation isn’t all that surprising. It points to a very active cycle of development with regard to these capabilities, countermeasures against them, and then new counter-countermeasures.

It is important to remember that the threat posed by drones, including lower-tier weaponized commercial types, is not new, as The War Zone regularly notes. At the same time, the very visible use of FPV and other drone types in the fighting in Ukraine has rammed the point home that these are real capabilities and ones that are only set to become more dangerous, and ubiquitous on and off traditional battlefields, as time goes on.

This, in turn, has heightened demand among armed forces around the world, including the U.S. military, for various tiers of anti-drone defenses, and not just on land. The War Zone recently explored in detail how tanks and other armored vehicles, especially, now need localized protection against these threats, which hard-kill active protection systems could help provide.

The emergence of an apparent wire-guided kamikaze drone being used by Russian forces in Ukraine is just the latest evidence of how real this threat is now and how it is continuing to evolve.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com