The head of U.S. Special Operations Command, U.S. Army Gen. Richard Clarke, recently highlighted the threat that various tiers of unmanned aircraft pose to U.S. forces deployed overseas, as well as to military and other targets abroad and within the United States. He further underscored that these dangers are only likely to grow and diversify as time goes on. Clarke added that finding ways to “defeat” hostile drones before they’re ever launched, including finding ways to restrict access to key supply chains and build international consensus about the risks of proliferation and other issues, will be just as important as developing systems to actually knock them out of the sky.

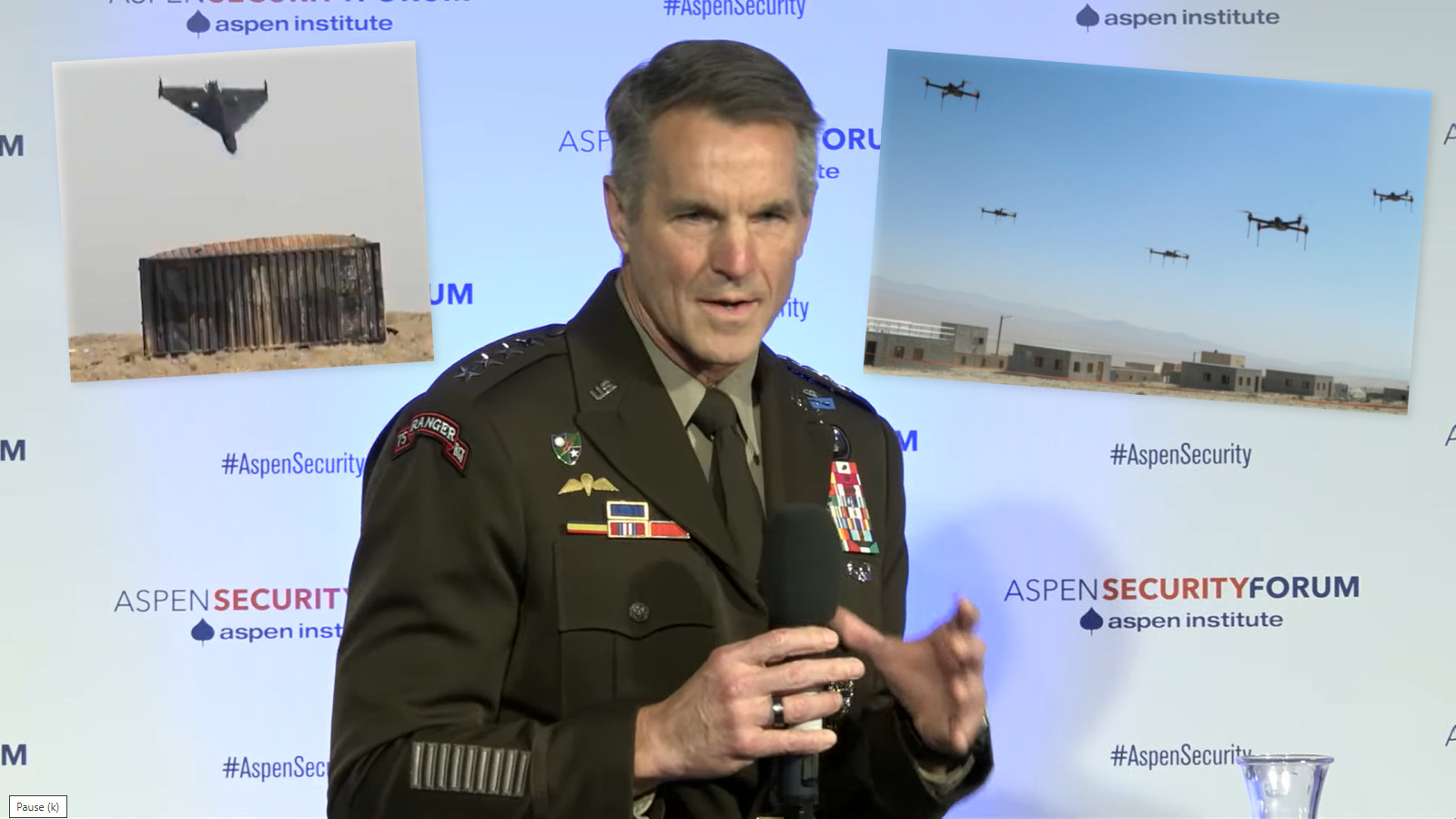

Clarke offered his perspective on the ever-growing drone threat and how to respond to it last Friday at the annual Aspen Security Forum, hosted by the Aspen Institute think tank. The general spoke alongside Sen. Joni Ernst, an Iowa Republican who is currently her party’s ranking member on the Senate Armed Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, and Rep. Jason Crow, a Colorado Democrat who sits on the House Committee on Armed Services and the House Intelligence Committee.

Clarke, Ernst, and Crow talked about challenges and opportunities in relation to other threats, such as chemical and biological weapons, cyber and information warfare, and food insecurity, as well. You can watch the full video of the panel discussion below.

“First, as we think about this problem, I’ve been in the Army for 38 years, and in my entire time in the Army on battlefields in Iraq, in Afghanistan, Syria, I never had to look up,” Gen. Clarke said by way of introducing the threat posed by unmanned aircraft. “I never had to look up because the U.S. always maintained air superiority and our forces were protected because we had air cover. But now with everything from quadcopters – they’re very small – up to very large unmanned aerial vehicles [UAV], we won’t always have that luxury.”

“The cost of entry into this, particular for some of the small unmanned aerial systems, is very, very low,” he added. “I think that this is something that’s gotta continue to go up in terms of our priority for the protection, not just of our forces that are forward today – that’s the current problem – but what’s gonna come home to roost. Some of these technologies could be used by our adversaries on our near abroad or even into our homeland.”

Clarke’s remarks echo comments from other senior U.S. military and other government officials in recent years, particularly with regard to the growing threats low-tier drones now pose to American troops even in relatively small conflicts against non-state actors. What he said here also reflects how an increasingly diverse set of actors, including militant and organized criminal groups, as well as various state and state-sponsored entities, are employing these capabilities outside of traditional battlefields for intelligence gathering purposes and direct attacks.

“We do see this as a growing problem, because if you look at the availability of inexpensive drones, you find that the violent extremist organizations that we battle around the globe have easy access to this technology,” Sen. Ernst said separately. “They don’t need to develop anything. All they need to do is hop on Amazon and they can buy a $300 drone that can be used against an adversary. And so, it is a real concern.”

Unmanned aerial threats, of course, aren’t simply limited to modified commercial and other lower-end systems. “When Russia is running out of them for Ukraine, and they’re going to Iran to go buy more, should cause us all a bit of concern, because you can see how valuable that they can be in the future fight,” Gen. Clarke used as an example. The U.S. government recently disclosed that it had intelligence indicating that the Russian government was looking to acquire hundreds of unspecified drones from Iran to support its ongoing war in Ukraine, as you can read more about here.

“As we look to the future, we know that the Chinese, the Russians, and others are putting a lot of money into what we call swarm technology,” Sen. Ernst added. “So, it’s not just the one-offs that are being purchased on the internet, but now we have near-peer adversaries that are developing swarm technology where they can use 100 to 200 different drones – highly evolved drones – that can attack our service members on the battlefield, perhaps disrupt a Superbowl game, whatever it might happen to be.”

Ernst’s mention of a scenario involving an adversary disrupting a Superbowl game further highlights how these potential threats, from state and non-state actors alike, could expand beyond a typical military context.

For additional context about how these threats are not only real, but evolving, just in the past few years, The War Zone has been the first to report on a number of concerning incidents. These include worrisome drone flights over sensitive U.S. military installations on Guam and the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant in Arizona, as well as how the U.S. Navy assessed that the Hong Kong-flagged cargo ship Bass Strait was likely the source of at least some of the drones that repeatedly harassed U.S. Navy warships off the coast of southern California in 2019.

Just last year, details also emerged about an incident that U.S. officials assessed to likely be the first ever instance of a drone being used in an attempted attack on domestic power grid infrastructure, as you can read more about here.

“So, we do have to focus not only on the drone technology, but then anti-drone technology,” Ernst said.

However, SOCOM head Gen. Clarke said the discussion had to move beyond just talking “about the defeat of the UAS [unmanned aerial systems] or the UAVs after they’ve already launched.” This was in response to a question from the moderator of the panel at Aspen, NBC News‘ Courtney Kube, about so-called “left-of-launch” options, that is to say options beyond an immediate physical reaction of some kind, for neutralizing or mitigating the threat posed by unmanned aircraft.

“I think there are opportunities for our government, for our intel agencies, and our Department of Defense” when it comes to “how do we stop those drones before they even launch,” Clarke said. He specifically talked about how deep intelligence about these threats, including the supply chains that support them, as well as international “norms of behavior” around drone use could be ways of addressing these issues before the danger becomes imminent.

While Clarke did not provide detailed examples of how these “left-of-launch” options might be implemented, there are very relevant real-world examples, some of which have become hot topics of public discussion just recently. In terms of supply chains, and the value of industrial intelligence, one need not look any further than the general’s mention of Russia potentially buying Iranian drones. Russian officials sourcing unmanned aircraft of any kind from Iran highlights, in part, the inability of its own industrial base to produce even lower-tier types in any real quantity. Crippling international sanctions have further limited Russia’s own ability to produce various kinds of unmanned aircraft, among other military hardware, because of the heavy reliance of those systems on foreign-made electronics and other components, something you can read more about in detail here.

Finding ways to further limit or otherwise control the access America’s adversaries may have to relevant technologies and supply chains could certainly offer additional ways to address these threats. This could potentially extend to new U.S. government rules and restrictions on the sale and/or purchase of various unmanned aerial systems, especially through online marketplaces.

However, for those kinds of restrictions to be at all effective, there would need to be at least a certain amount of international consensus. That speaks to Clarke’s comments on how the U.S. government could seek to address these threats on some level through the establishment of new norms around drone use on and off the battlefield.

During the panel talk at Aspen, Rep. Crow from Colorado made separate, but related remarks about how in his opinion discussions about the threats that drones pose will increasingly have to address adjacent moral and ethical issues, especially in regards to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

“We have some really big unanswered questions, too, that we have to have some public debate about. And that’s just not the technology and investment, but we have to have a discussion around what is the role of AI going to be. Because we have discussions as a democracy, and we would take into consideration the moral and ethical implications of drones in ways that some of our adversaries do not,” Crow said. “We have to think about whether or not humans will remain in the kill chain, because some of our adversaries have decided that they will not, and that the targeting will be done much quicker, and without people making those decisions.”

It is important to remember that International consensus building is often fraught with pitfalls and is never a guarantee against bad actors acting badly. At the same time, broader buy-in on the part of the international community can lay useful foundations for collective responses, whether they be sanctions or something else, in a crisis.

It is clear from Clarke’s comments at Aspen that meeting the very real challenges that drones pose on and off the battlefield through interventions in supply chains, new norms, and other novel avenues are all parts of a broad, multifaceted approach, and that no one single course of action will address all of the issues by itself.

There’s also no doubt that systems to actually bring down hostile drones, through kinetic or non-kinetic means, will still be important parts of the equation. Sen. Ernst and Rep. Crow both highlighted the need for general reforms in how the U.S. government develops and acquires military and other technologies in order to defend against these threats.

“I don’t think we are ever doing enough, frankly, given some of the investments by China in particular in this area,” Crow said. “Our adversaries are using COTS stuff – commercial-off-the-shelf – they’re using very inexpensive… systems, and they recognize that the technological evolution of any system is 18 to 24 months, as opposed to 10 to 15 years, like it used to be.”

These are all issues that The War Zone has been highlighting for years in discussions about very real threats posed by all kinds of different drones and the proliferation of those capabilities, along with sounding the alarm about how the U.S. military and other branches of the government have long lagged behind the technology in developing comprehensive responses to these issues. Beyond all this, it’s important to note that now, especially at the lower end of drone threats, various key technologies are now basic consumer goods or are otherwise readily available commercially. This in turn could present hurdles to the kind of left-of-launch options that Clarke advocated for at Aspen last week.

What is increasingly indisputable, as Clarke, Ernst, and Crow all made clear during the panel talk at Aspen, is that drones of various kinds present an array of very real threats to a host of vastly different targets, military and otherwise, and that outside-the-box thinking will be necessary to address them in their totality.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com