The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has called into question the viability of using the C-130J Hercules cargo aircraft as the basis for a new plane, called the E-130J, to support the U.S. Navy’s Take Charge And Move Out (TACAMO) mission. TACAMO is a key component of the sea leg of America’s deterrent triad, offering aerial command and control support for nuclear ballistic missile submarines, including the ability to send them orders to launch strikes while they are submerged. Aircraft assigned nuclear support missions like TACAMO, such as the Navy’s forthcoming turboprop-powered E-130Js and the existing E-6B Mercury jets they are set to replace, are commonly called ‘doomsday planes.’

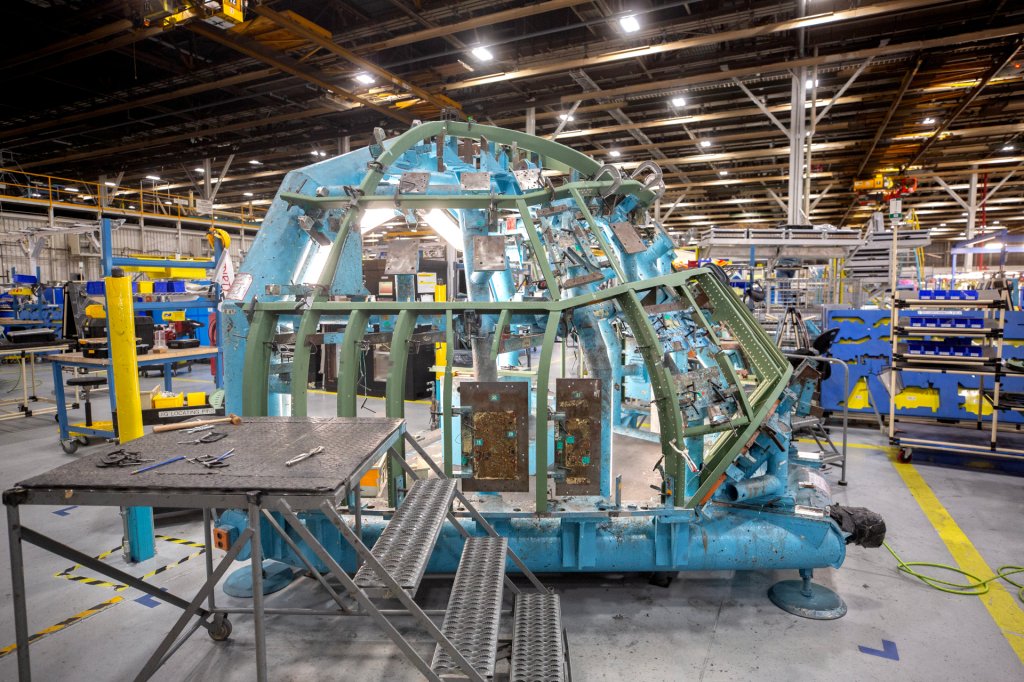

GAO, a Congressional watchdog, highlighted concerns about the use of the C-130J platform and other aspects of the E-130J effort in an annual report released yesterday assessing the state of multiple high-profile procurement programs across the U.S. military. The Navy first publicly announced its intention to acquire new TACAMO aircraft based on the C-130J-30 subvariant, which has a longer fuselage than the baseline type, in 2020. Northrop Grumman has since been selected as the prime contractor for the conversion work, and the initial E-130J prototype is now in the very early stages of construction.

The Navy currently has a fleet of 16 E-6B Mercury aircraft, based on the now long-out-of-production Boeing 707 airliner, to perform the critical TACAMO mission. The aircraft had originally entered service as E-6As starting in 1989 before being upgraded to their current configuration. The E-6Bs are also designed to support a U.S. Air Force nuclear mission set called the Airborne Command Post (ABNCP), and more commonly known by the nickname Looking Glass, which involves providing aerial command and control support to nuclear-capable bombers and silo-based Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles. As part of that role, the Mercury jets are able to initiate the launch of Minuteman IIIs while in flight.

“The C-130J aircraft – selected 4 years before E-130J’s development start – may not meet operational availability requirements. The E-130J’s technical risk assessment highlighted the complexity associated with integrating E-130J systems onto this aircraft,” per GAO. “The Navy’s technical risk assessment team expects the integration risks to translate to manufacturing issues given the potential deviation from standard components and the security environment required.”

More broadly, “the program’s acquisition strategy centers on a traditional linear development approach, which our work has shown greatly impedes application of leading practices needed to develop and deliver innovative capabilities faster,” GAO’s report warns. “Further, the lack of an iterative approach will inherently impede rapid updates to the E-130J design should the program determine that changes are needed to meet evolving user needs or to accommodate new technologies – undermining its modular open systems approach that allows for faster upgrades.”

“The Navy’s premise is that it can design a system that will operate effectively for decades using legacy technologies – even though history is littered with examples of weapon systems retired prior to the end of their planned service lives due to obsolescence,” the report adds. “In support of this aim, the Navy established highly detailed system capabilities and performance measures prior to E-130J development start, curbing the program’s ability to refine capabilities during design to ensure that it continues to meet user needs as development progresses.”

GAO’s latest annual assessment does not elaborate on the “operational availability requirements” in question or its specific concerns about the E-130J to meet them. The report does include a paraphrased response from the Navy defending the decision to use the “proven” C-130J platform that also “acknowledges technical risk.” The E-130J program office also told GAO that “it executed risk reduction contracts with subcontractors to address obsolescence and size, weight, and power-cooling risks” before formally initiating the development process.

It is immediately worth noting here that before the Mercury jets entered service, the Navy operated EC-130Q TACAMO aircraft based on the older C-130H variant of the Hercules. Those aircraft were not configured to also perform the Looking Glass mission. The arrival of upgraded E-6Bs in the 1990s led to the consolidation of those two mission sets on a single aircraft. In addition, C-130Js and a plethora of subvariants thereof are also in widespread service across the U.S. military already. The average mission-capable rate for Air Force cargo-carrying C-130Js during the 2024 Fiscal Year was just shy of 72%, much better than many other types, according to a report in February from Air & Space Forces Magazine.

At the same time, the heavily modified E-130J is set to be very significantly different inside and out from the baseline J model Hercules aircraft, as you can read more about here. As alluded to in the GAO report, the unique and highly sensitive systems required for the TACAMO mission present substantial demands on any aircraft when it comes to things like “size, weight, and power-cooling.” All of this would add complexity to ensuring the operational availability of the future E-130Js compared to typical C-130Js.

When plans for a new C-130J-based TACAMO plane first emerged in 2020, TWZ highlighted questions about that course action, but also the benefits of doing so, writing:

“It’s certainly worth pointing out that the E-6Bs, conversions of what were some of the last and most modern 707 airliners built, were larger and higher performance platforms than the EC-130Qs. The C-130J-30 is certainly a more capable aircraft than the C-130H on which the EC-130Q was based, but it won’t have the base speed and altitude capabilities of an airliner-sized multi-engine jet. Compared to the Mercuries, any TACAMO-configured C-130J-30 would not be able to get on station as quickly, or fly as high, limiting its ability to get above bad weather or establish a better line of sight for its communications systems.”

“At the same time, as the Navy itself has noted, the C-130J-30 platform does immediately open up the ability to use a larger number of air bases, airports, and airfields, including austere ones that the E-6B cannot operate from. This could be very useful in a contingency scenario where an opponent may have destroyed or otherwise rendered unusable many well-established bases, as well as larger secondary dispersal sites, which include large commercial airports. Being able to fly from smaller, tertiary locations could help to ensure that the TACAMO mission continues without significant disruption under such circumstances. This is also true during peacetime as targeting the TACAMOs on the ground would be much harder if they could easily operate from and sit alert at a much larger number of airports.”

“A C-130J-30 configured for the TACAMO mission would certainly have a mid-air refueling capability and the Hercules is already a platform that has demonstrated the ability to loiter over particular areas for long periods of time. Unlike the Boeing 707, the C-130J is still in production, as well, meaning that TACAMO aircraft based on this plane would be inherently easier to maintain and support logistically, and may also be easier to convert to this specialized configuration begin with. As time goes on, the J looks set to increasingly become the default base C-130 model across the U.S. military, as well. Compared to the long out of production 707-based E-6, support for the C-130J is already distributed across the U.S., and beyond. Training C-130J crews is even an easier proposition.”

The broader concerns raised in GAO’s report about potential impediments to updating and modifying the E-130J’s systems underscore separate questions about the future of the Looking Glass mission. To date, the Navy has only confirmed that the E-130J will be configured to perform the TACAMO mission. As noted earlier, separate platforms had performed the TACAMO and Looking Glass missions prior to the E-6Bs entering service.

Other aircraft, like the Boeing 747-based E-4C Survivable Airborne Operations Center (SAOC) jets that the Air Force is in the process of acquiring now, might also take on the Looking Glass role, at least in part, in the future. The E-4C, and the E-4B Nightwatch aircraft they are set to replace, are also ‘doomsday planes,’ but are configured to act as much more robust flying command centers than the E-6Bs.

In the meantime, the aging E-6B fleet is facing readiness and other challenges of its own. In 2021, the Navy notably acquired an ex-Royal Air Force E-3D Sentry airborne early warning and control aircraft, another Boeing 707-based type, for conversion into a dedicated TE-6B crew trainer expressly to help relieve strain on the operational Mercury jets. The service is now in the process of disposing of that aircraft, something TWZ was first to report.

“On Nov. 30, 2023, the Navy issued a stop-work order on its contract with Northrop Grumman Corp. to convert the E-3D acquired in 2021 from the Royal Air Force into an in-flight trainer (IFT) for the E-6B Mercury. The cost of the conversion, including meeting airworthiness requirements, exceeded available funding, leading the Navy to conclude that a different course of action (COA) was needed,” Naval Air Systems Command’s (NAVAIR) Airborne Strategic Command, Control and Communications Program Office told TWZ in a statement just yesterday. “The Navy will harvest all applicable parts for sparing before divesting of the E-3D. The value of those parts is estimated to exceed the $15 million purchase cost of the aircraft, ensuring the Department of Defense recoups its investment.”

In addition, “the Navy awarded a contract to provide Contracted Air Services (CAS), Contractor Owned Government Operated (COGO) 737 NG In-Flight Trainer (IFT) aircraft services for E-6B Pilot Training. On May 30, 2025, the first Training Flight occurred.”

It is unclear when the E-130J might begin to enter service. Past Navy budget documents have laid out plans to order three of the aircraft in Fiscal Year 2027 and six more in Fiscal Year 2028. Some portion of those planes are expected to be test articles rather than operational examples, as well.

There is now considerable uncertainty around the defense spending plans across the U.S. military, in general. The Pentagon has yet to release a public version of its next budget request, for the 2026 Fiscal Year, which is highly unusual.

How the concerns GAO has now publicly raised might factor into the E-130J plan going forward remains to be seen.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com