The U.S. military is pumping the brakes on a high-profile program that intended to convert an MC-130J special operations tanker/transport aircraft into a floatplane. U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) has largely blamed budgetary pressures for this decision. At the same time, SOCOM is also actively exploring alternative ways of providing added air mobility, especially in a potential conflict in the Pacific region against China.

Air Force Col. T. Justin Bronder, SOCOM’s program executive officer for fixed-wing aviation programs, provided an update on what is formally known as the MC-130J Amphibious Capability (MAC) project at the annual SOF Week conference earlier today. The Air Force first unveiled the MAC effort in 2021, but the schedule for the planned flight testing of the converted Commando II aircraft had repeatedly been pushed back.

“Looking at kind of the budget projections, and some of the actual cost-effectiveness [considerations] of that particular kind of integration effort, [we] decided it was best to kind of take all that work and transition it for potential kind of future use,” Bronder said. “And [we] kind of reach[ed] that first milestone of understanding what it would take to field MAC.”

SOCOM is now “kind of hitting a pause on any specific plans to actually operationalize that [MAC] right now as we look at… the cost-effectiveness of what we learned from all that data, and certainly what the requirements might actually be for AFSOC [Air Force Special Operations Command] when it comes to amphibious operations in the future,” Bronder added.

The U.S. military’s Fiscal Year 2025 budget request, which was rolled out in March, had included $11.5 million for SOCOM to pay for the fabrication of initial components necessary for the MC-130J floatplane conversion. In its proposed Fiscal Year 2024 budget, the Pentagon had asked for $15 million for the MAC project, and the year-over-year “decrease of $3.5 million… is due to [the] completion of detailed design activities in FY 2024,” according to official budget documents. The Pentagon was limited in how much funding it could ask for in the upcoming fiscal cycle under the provisions of the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which Congress passed and President Joe Biden signed into law last year.

The U.S. military has already had some of an on-again-off-again relationship with MAC. This is not the first time plans related to the project have been put on hold, including ostensibly due to funding constraints.

“For a variety of reasons, at this time we do not have the capability demonstration scheduled,” an AFSOC spokesperson told The War Zone last year. “Those reasons vary from funding challenges to a recent reprioritization of capabilities.”

Col. Bronder did stress today that MAC “certainly is a capability we could field if called upon” and highlighted the value of the work that has already been done on the project.

“The team really got after that [MAC] with some aggression… that really kind of typifies SOCOM acquisitions. [They] completed a very successful technical deep dive in close partnership with our industry partners… to come up with a real rich, data-driven model on just how to make something like MAC on the C-130 fleet operational… [that] included dynamic wind tunnel testing [and] included hydrostatic testing,” Bronder explained. “And I think the neatest part of that was [taking]… all that information and put[ting] it into a new living digital environment.”

It is worth noting that MAC is not the first time that amphibious and seaplane C-130 concepts have been explored by the aircraft manufacturer, now Lockheed Martin, and branches of the U.S. military.

SOCOM’s top fixed-wing aviation acquisitions officer also explicitly touted the strategic signaling potential of acquiring and fielding something like an amphibious MC-130J.

“I think the value of that in the messaging you see with something like MAC is pretty clear, right?” he said. “Taking our C-130 fleet and making it readily adaptable to kind of operate all over the backyard of a pacing threat and near-peer competitor in China.”

Conflict and contingency scenarios in the Pacific region, especially a potential high-end fight against China continue to provide the primary use cases for capabilities MAC would offer to SOCOM and the rest of the U.S. military, as The War Zone has explored in the past. That being said, amphibious C-130s could offer valuable added runway-independent air mobility for operations elsewhere in the world, too.

China has also developed a new large amphibious transport aircraft called the AG600. The War Zone has highlighted in the past how this aircraft is ideally suited to supporting the People’s Liberation Army’s man-made outposts in the South China Sea.

The U.S. military is otherwise increasingly concerned about the vulnerability of large, established bases, especially in the context of a possible future large-scale conflict, such as one against China. There is great interest now in a variety of aviation concepts that have little or no need for traditional runways.

“In the meantime, …SOCOM is very much pathfinding with DARPA [the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency on the High-Speed Vertical Takeoff and Landing [project],” Bronder said today after discussing the current state of MAC. “That is a DARPA hard challenge… a vertical takeoff and landing aircraft that can go well over 400 knots with some range and nominal payload.”

HSVTOL is technically the SOCOM companion to the DARPA program in question, which is actually called Speed and Runway Independent Technologies (SPRINT), but the two efforts a directly tied to each other.

The HSVTOL/SPRINT “effort is kind of working through some white papers and modeling, and working through a down selection now to a couple of vendors and industry partners,” according to Bronder. “We’re going to… essentially build up to a preliminary design… type of review next summer to further down-select, [and] ultimately looking forward to a flying prototype demo in the late 2020s.”

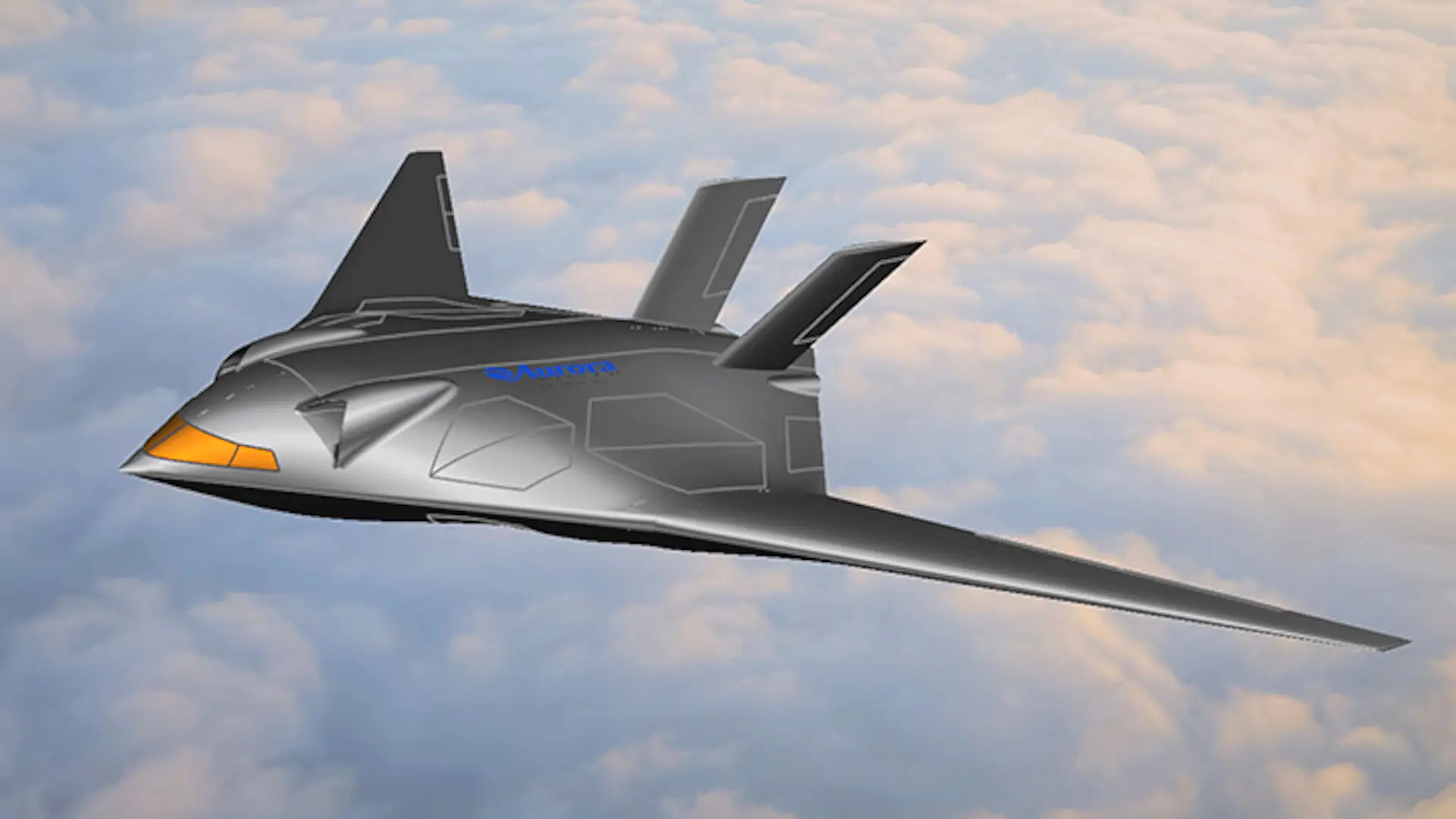

On April 30, DARPA awarded a new contract valued at just under $25 million to Aurora Flight Sciences, a subsidiary of Boeing, to advance in the SPRINT program. You can read more about what is known about Aurora’s proposed design here.

It is not immediately clear if any of the companies that had been on contract in the previous phases of SPRINT – Bell, Northrop Grumman, and the Piasecki Aircraft Corporation – are still doing work under that project. Since at least last September, Bell has been testing non-flying test articles as part of work to develop technologies relevant to HSVTOL and SPRINT at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

“I’ll note that that’s an effort there where we are more and more kind of closely working with the services, especially the Air Force, to see the utility of this capability we’re kind of pathfinding around a SOF [special operations forces] use case, because we think it’s very relevant to where the Air Force needs to go with contested logistics,” SOCOM’s Col. Bronder noted. “When we get to that flying prototype in the late 2020s, I think we’re looking to be well-postured there for success, and for a potential transition with a willing service partner. … [SPRING is] really moving the needle on a capability that I think cuts across where a lot of the services want to be.”

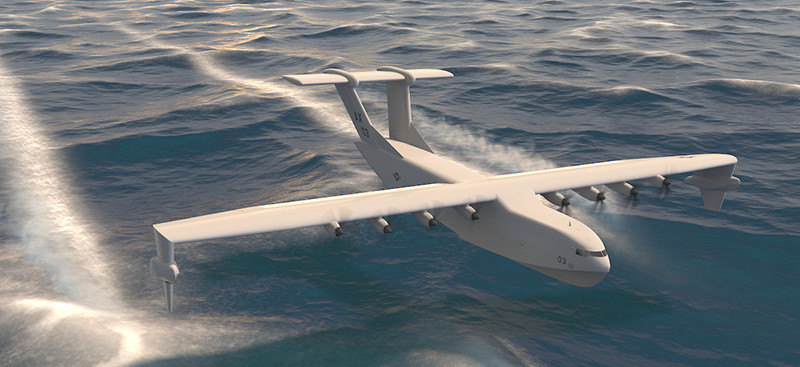

DARPA is also working on a separate project, called Liberty Lifter, which is exploring potential designs for long-range and low-cost amphibious transports using wing-in-ground-effect (WIG) ekranoplan-like concepts. Aurora Flight Sciences (teamed with Gibbs & Cox, a Leidos company, and ReconCraft) and General Atomics (partnered with Maritime Applied Physics Corporation) are currently working on designs as part of that program, which you can read more about here. The current plan is to eventually pick one of the two competing teams to build a full-scale flying demonstrator.

The pause in MAC could also reinvigorate interest in the Japanese ShinMaywa US-2 seaplane, a very capable existing option. Since last December, authorities in Japan have been relaxing arms export restrictions, which has been seen in part as opening the door to new sales opportunities for the US-2 specifically.

New and/or refined tactics, techniques, and procedures may be another way of getting at the kind of added mobility SOCOM and the Air Force had been looking at with MAC. Air Force Lt. Gen. Tony Bauernfeind, the head of AFSOC, talked about the renewed importance of being able to operate C-130s and other aircraft from beaches and other impromptu runways at a roundtable at the Air & Space Force’s main annual conference in September 2023.

“We’re … looking at the ability for beach landings,” Bauernfeind said at that time. “There’s a lot of 3,000-foot [long] straight beaches that we can bring MC-130s and CV-22s into to deliver the effects we need.”

“Our adversaries have watched the American way of war for several decades, and they are going to hold our initial staging bases and our forward operating bases at risk,” Bauernfeind added. “They understand that [the way] to slow the American joint force down is … to target our basing.”

This is a core reality that led to the MAC project in the first place. However, for the moment at least, the idea of addressing these issues, even in part, with an amphibious MC-130, has been shelved again.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com