The U.S. Air Force is at least researching what it might take to develop a nuclear-armed hypersonic boost-glide vehicle with a range equivalent to a traditional intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM. This vehicle could potentially go on top of the service’s future Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent ICBMs, which are now in development. Publicly, the hypersonic weapons programs now in progress across the U.S. military are all conventionally-armed.

Aviation Week was first to report on this potential nuclear hypersonic weapon effort on Aug. 18, 2020, based on information the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center had included in a request for information posted online six days earlier. That document, which was marked “For Official Use Only” and has since been taken offline, outlined seven potential upgrade tracks for an ICBM with a “modular open architecture.”

This is understood to refer to the forthcoming Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), because the existing Minuteman III IBCM was not designed with these features in mind. One of those areas of interest is “thermal protection system that can support [a] hypersonic glide to ICBM ranges.”

“GBSD does have an open architecture. It gives us an ability to incorporate emerging technologies we need to counter whatever threats we face in the future,” Air Force Lieutenant General Richard Clark, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration, said in response to a specific question about a potential nuclear-armed hypersonic payload during a virtual event hosted by the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute on Aug. 19, 2020. “So as we bring the system [GBSD] online, we will ensure that we have the ability to roll different technologies in and incorporate that into GBSD.”

In response to a follow-up question from Steve Trimble, Aviation Week‘s Defense Editor and good friend of The War Zone, Clark explicitly said that a nuclear-armed hypersonic boost-glide vehicle was not in the minimum “threshold” requirements for the GBSD program. However, as Trimble astutely pointed out, this only raises questions about what the program’s more ambitious “objective” requirements might include.

Senior Department of Defense officials had told Trimble for his original story that there is a policy in place now that expressly limits hypersonic weapons developments to the non-nuclear realm. Of course, basic research into the requirements for a future nuclear hypersonic weapon would not necessarily violate that policy.

Kingston Reif, the Director for Disarmament and Threat Reduction Policy at the Arms Control Association, a non-partisan organization that works to promote “public understanding of and support for effective arms control policies,” also pointed out on Twitter that President Donald Trump’s Administrations’ 2018 Nuclear Posture Review included passages that could indicate an interest in nuclear-armed hypersonic developments.

“DoD will explore prioritization of existing research and development funding for advanced nuclear delivery system technology and prototyping capabilities,” that policy document said. “This will support the U.S. development of hedging options and focus, as necessary, on the rapid development of nuclear delivery systems, alternative basing modes, and capabilities for defeating advanced air and missile defenses.”

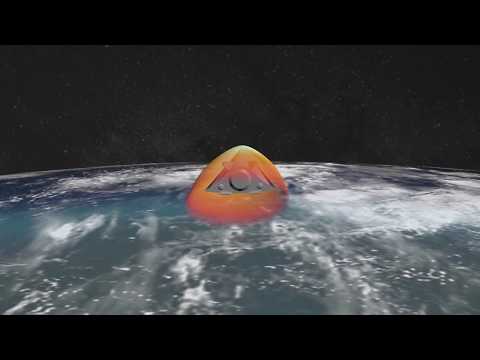

Interest in hypersonic weapons, in general, both within the U.S. military and elsewhere around the world, is heavily driven by a desire to ensure strikes can successfully make it past increasingly advanced integrated air and ballistic missile defense networks. Hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, a notional design of which is seen at the top of this story, are unpowered and generally use a rocket booster to loft them to an optimal altitude and speed.

Once there, they glide back down to their target at hypersonic speed, defined as Mach 5 or above, following a varying trajectory, as well as maneuvering laterally. This is a much less predictable flight path compared to that of reentry vehicles on traditional ballistic missiles. This, together with the vehicle’s high speed, makes it difficult for an opponent to protect against these weapons or otherwise relocate critical assets before it actually hits its target.

This could also be, at least in part, a direct response to developments among potential American adversaries. Russia has already fielded some number of silo-launched Avangard missiles, which are tipped with at least one nuclear-armed hypersonic boost-glide vehicle. China is known to be working on this type of hypersonic weapon, as well, though it’s not clear if that country’s military envisions a strategic nuclear role for them.

The disclosure that the United States may at all be interested in the development of a nuclear hyperosnic weapon with ICBM range also comes amid tense negotiations between U.S. and Russian government officials over extending the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START. The treaty limits how many nuclear warheads each country can have, as well as the total numbers of certain delivery systems. Russia has declared its Avangard missiles as being covered by the treaty, but has said, at least at present, that other novel nuclear weapons, such as a nuclear-powered cruise missile and a long-range nuclear-powered torpedo, are not within that agreement’s purview. The U.S. government has also, so far unsuccessfully, tried to bring China into these negotiations to craft some sort of trilateral arms control deal.

The U.S. military has already fielded submarine-launched ballistic missiles with lower-yield nuclear warheads in direct response to concerns about Russia’s nuclear modernization efforts and doctrine, especially a potential “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy that could see the Kremlin employ a limited tactical nuclear strike in an effort to effectively settle a tertiary conflict before the United States or its allies could response. Experts dispute whether this doctrine actually exists. Regardless, Russia has made it clear that it will not be able to tell if an incoming weapon has a lower-yield warhead on top and will treat them the same as any other nuclear strike, triggering a massive retaliatory response.

Fielding future GBSDs with nuclear-armed hypersonic boost-glide vehicles might raise a separate discrimination issue in that opponents will very likely not be able to tell if an incoming hypersonic weapon is nuclear or conventionally armed. However, the conventional hypersonic boost-glide vehicles that the U.S. military has in development now will be fire from road-mobile launchers, submarines, and aircraft, which could make it easier to separate them from the silo-launched GBSDs.

At the same time, it remains unclear how far along the U.S. Air Force may be in even considering arming its GBSDs with these hypersonic weapons. The new ICBMs are not set to enter service until the late 2020s or early 2030s. Subsequent upgrades for those missiles, which is how the Air Force framed the possible addition of a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle payload, would likely come sometime after that.

Still, it’s notable that the service is exploring the option at all, which would represent a significant new addition to America’s nuclear deterrent arsenal.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com