The U.S. Air Force is looking to stop work on an air-launched missile that uses common unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle, which remains under development for the U.S. Army and Navy. Both of those services are pushing ahead with plans to use that vehicle as the warhead on new ground and sea-launched weapons, respectively. The Navy wants to nearly double funding for its portion of the program in the next fiscal year.

The Air Force first announced its desire to end the Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon, or HCSW, which is pronounced “hacksaw,” on Feb. 10, 2010, as part of the rollout of the Pentagon’s proposed budget for the 2021 Fiscal Year. Lockheed Martin won the contract, which had an estimated value of up to $928 million, to develop HCSW in 2018. The Air Force had received more than $571 million, in total, for work on this hypersonic missile in the Fiscal Year 2019 and 2020 budgets. It’s important to note that Congress still has to approve the new plan to cancel HCSW.

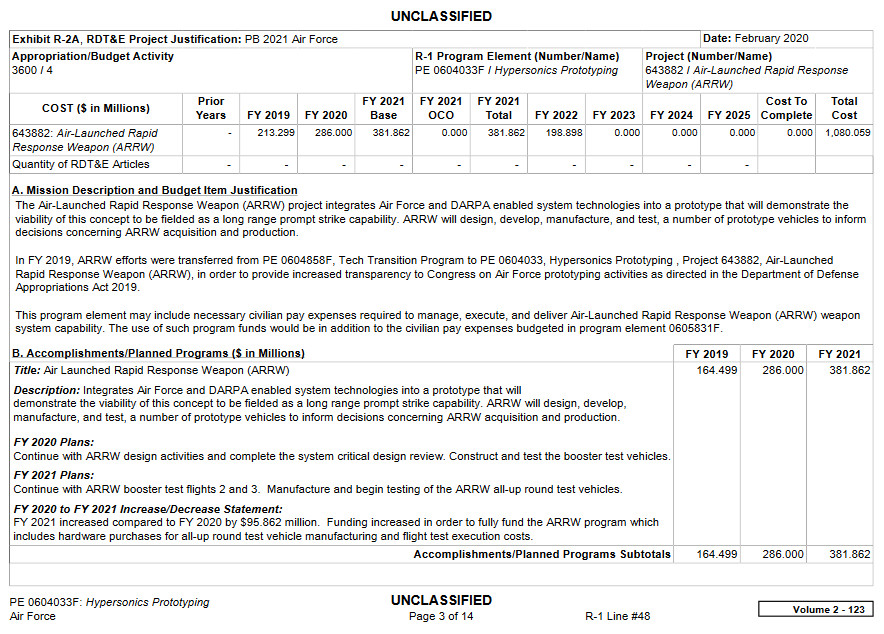

“Funding decreased due to higher Department of Defense and Air Force priorities to fund only one of the two Air Force hypersonic prototyping efforts,” an Air Force budget document explains as justification. The service is continuing with the development of the AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon, or ARRW, which is pronounced “arrow.”

The Air Force’s Fiscal Year 2021 budget request asks for just under $382 million for continued work on ARRW, almost $96 million more than it received for this program in the previous fiscal cycle. One of the service’s B-52 bombers carried a captive carry ARRW test article on a flight test for the first time last year. At present, the program’s goals for 2020 include the construction and test of this weapon’s rocket booster, which will be followed in 2021 by additional booster tests and the construction and test of a complete prototype missile.

The primary difference between HCSW and ARRW is the design of the unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle. HCSW’s design is a conical one based on the Common Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB) that the Army and Navy are developing for their ground-launched Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) and sea-launched Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) programs, respectively. ARRW will use a wedge-shaped glide vehicle derived from the design that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is working on as part of its Tactical Boost Glide (TBG) program.

The conical design is seen as less risky, but also less capable in terms of both maneuverability and range than a wedge type vehicle. Both types share the same basic concept of operation, with a rocket booster propelling them to an optimal speed and altitude, after which they glide along a relatively level trajectory toward their targets at extreme speeds.

As with ARRW, the B-52 is also intended to be the primary launch platform for HCSW, a flight test for which had been scheduled to occur in December 2020. It’s unclear whether or not that will now occur, as the Air Force has said that work on HCSW will still help inform other hypersonic developments.

“The HCSW team pioneered significant advancements in hypersonic technology development and integration of existing, mature technologies for use in various hypersonic efforts across the Department of Defense, including Army, Navy, and Missile Defense Agency programs,” Air Force spokesperson Ann Stefanek told Defense News on Feb. 10. “The HCSW team successfully met all developmental milestones. These advancements will serve to expedite the generation and demonstration of various hypersonic weapon capabilities in the near future.”

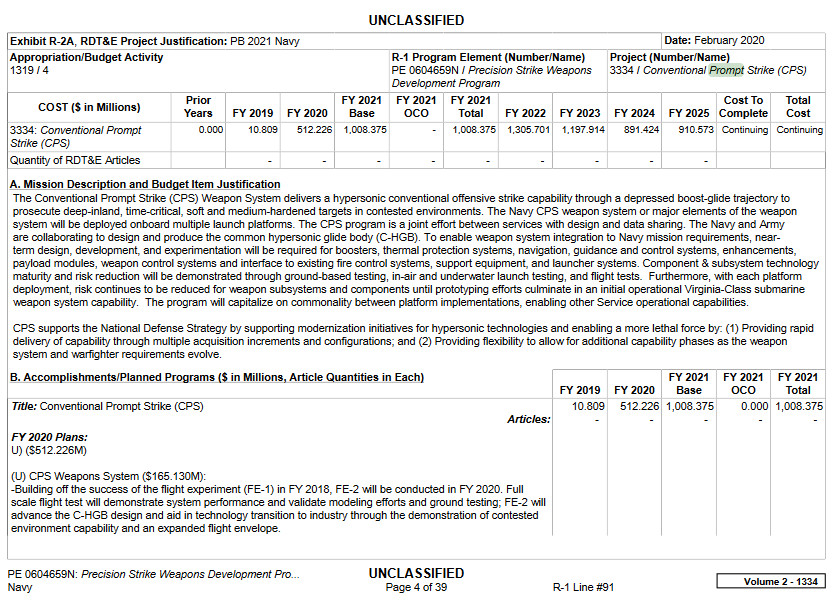

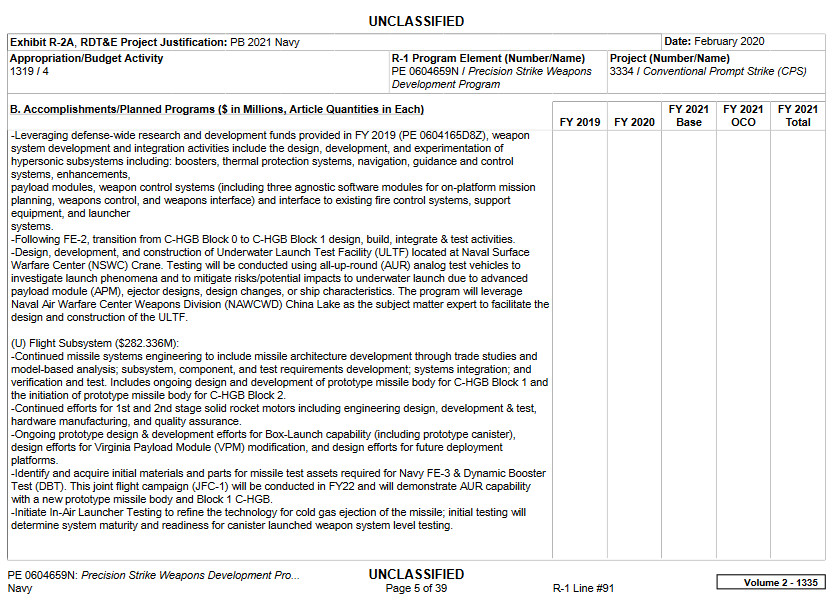

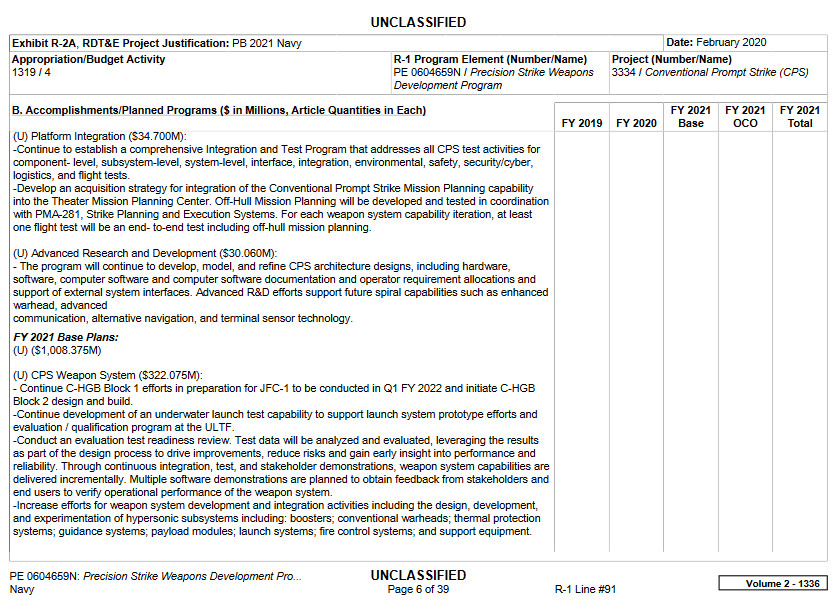

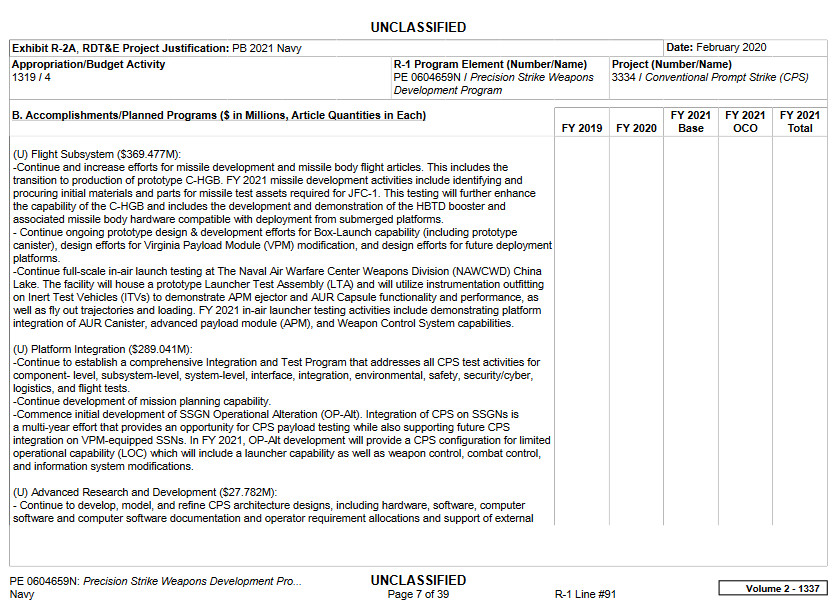

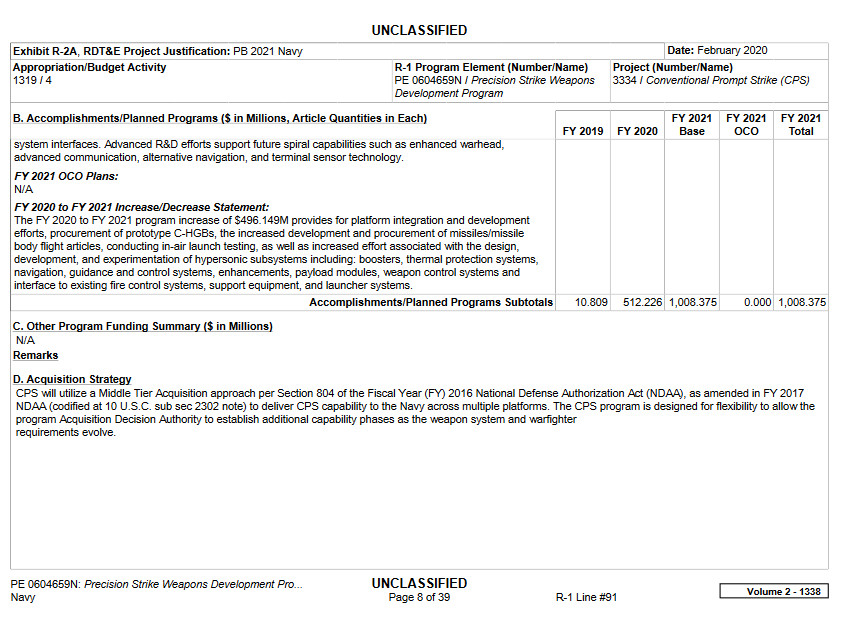

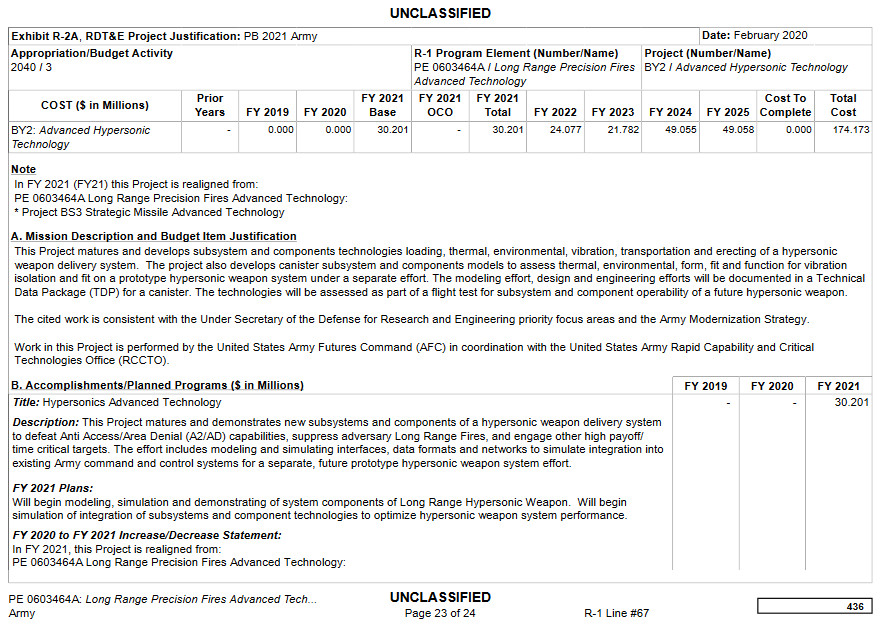

The Air Force’s intention to cancel HCSW has not slowed Army and Navy interest in their conical boost-glide vehicle design or their respective complete weapon systems. Just the opposite. The Navy’s Fiscal Year 2021 budget proposal requests a little over $1 billion for Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS), up from $512 million in the 2020 Fiscal Year budget. The Army is looking to create an entirely new budget line for its Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) and is asking for just over $30 million in funding for that project in the upcoming fiscal cycle.

The Navy is still planning to conduct another CPS flight test this year, which it expects to follow up with a joint flight test with the Army next year. The Army and Navy weapons will share a common booster and other features, along with the same conical boost-glide vehicle.

As a conventional weapon, the Navy expects to deploy the CPS missile on its four Ohio class guided missile submarines, as well as its future Block V Virginia class attack submarines, the latter of which will feature four suitable large launch tubes as part of the integration of the so-called Virginia Payload Module (VPM). A future, conventionally-armed “large payload submarine” could potentially carry these weapons, as well. Part of the funding the Navy wants for CPS in Fiscal Year 2021 would go toward continuing work in support of eventually integrating the missile on the Block V Virginias.

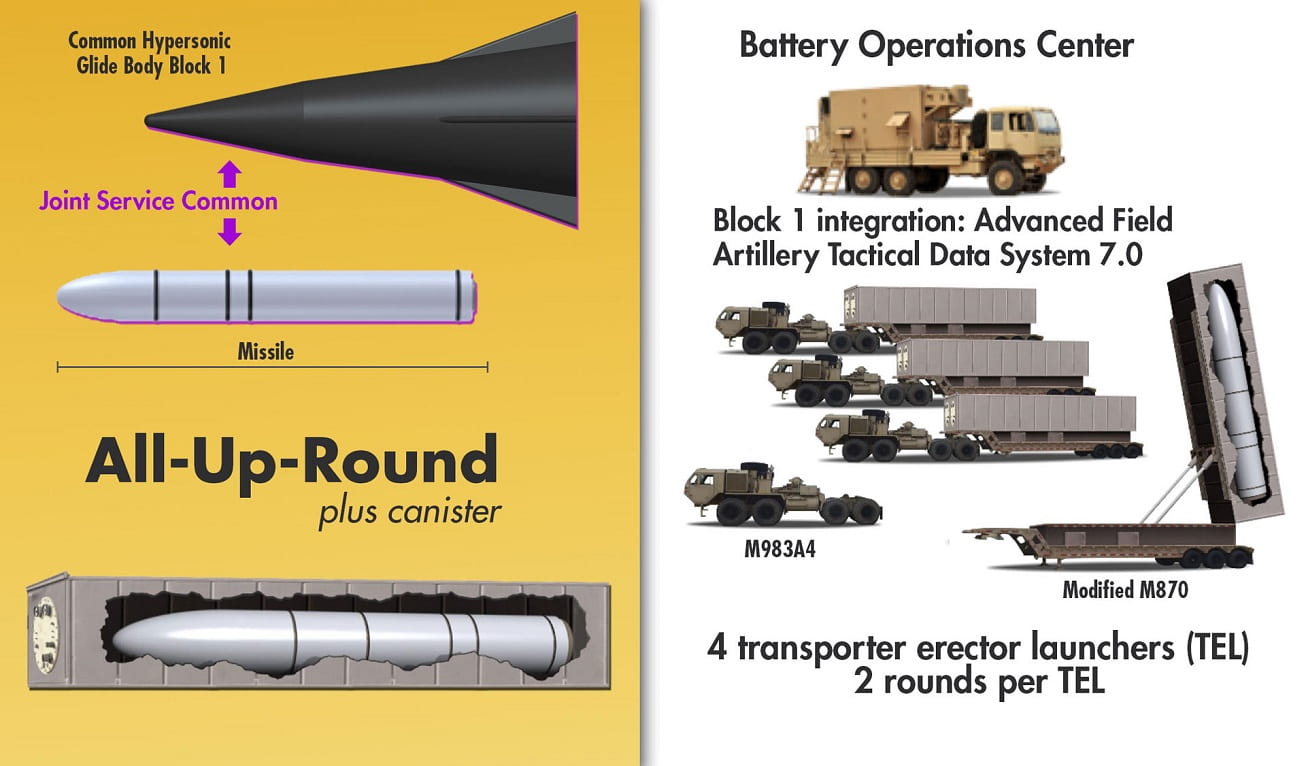

The Army plans to deploy the LRHW on a road-mobile launcher. The service’s Fiscal Year 2021 funding request for this program would go toward ” modeling, simulation and demonstrating of system components” and the goal is to “begin simulation of integration of subsystems and component technologies to optimize hypersonic weapon system performance” that year.

All told, the Air Force’s decision to abandon its HCSW program, while the Army and Navy continue with their related efforts, makes a certain amount of sense. HCSW and ARRW offer duplicative capabilities in many respects and, while the latter is more complex, DARPA is already funding risk reduction work in the form of the separate TBG program.

At the same time, if ARRW runs into complications and delays, it is very possible that the Air Force could again shift its priorities and leverage the Army and Navy’s work on CPS and LRHW to develop a HCSW-like interim system. Beyond that, Lockheed Martin is the prime contractor for both CPS and LRHW and has already left the door open for possibly restarting the HCSW program in the future.

“No layoffs are planned given the magnitude of work we have and if the Government should decide to restart, we will be ready,” Lockheed Martin told CNBC on Feb. 10.

All told, the Air Force’s decision to halt work on HCSW, at least for the time being, seems to be a reasonable one in light of the new, relatively flat defense budget. Regardless, hypersonic weapons, as well as defenses to shield against foreign designs, clearly remain a high priority across the U.S. military.

If ARRW runs into trouble, or the service’s budget priorities shift once again, it may well turn out that reports of the death of this particular hypersonic weapon program were premature.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com