China’s has become the first country ever to land a spacecraft on the far side, or “dark side,” of the Moon, a major achievement for its civilian space program. The mission offers numerous scientific research opportunities, but there is also a possibility that it could be another stepping stone to improving and expanding Chinese military capabilities in space.

The lander, known as Chang’e 4, touched down in the Von Kármán crater at around 9:30 PM EST on Jan. 2, 2019. The China National Space Administration (CNSA) had launched the craft on top of a Long March-3B/G3Z space launch rocket on Dec. 7, 2018. It then entered orbit around the Moon on Dec. 12, 2018.

“China is on the road to become [sic] a strong space nation,” Wu Weiren, the chief designer of the Chang’e 4, told state-run CCTV after the landing. “And this marks one of the milestone events of building a strong space nation.”

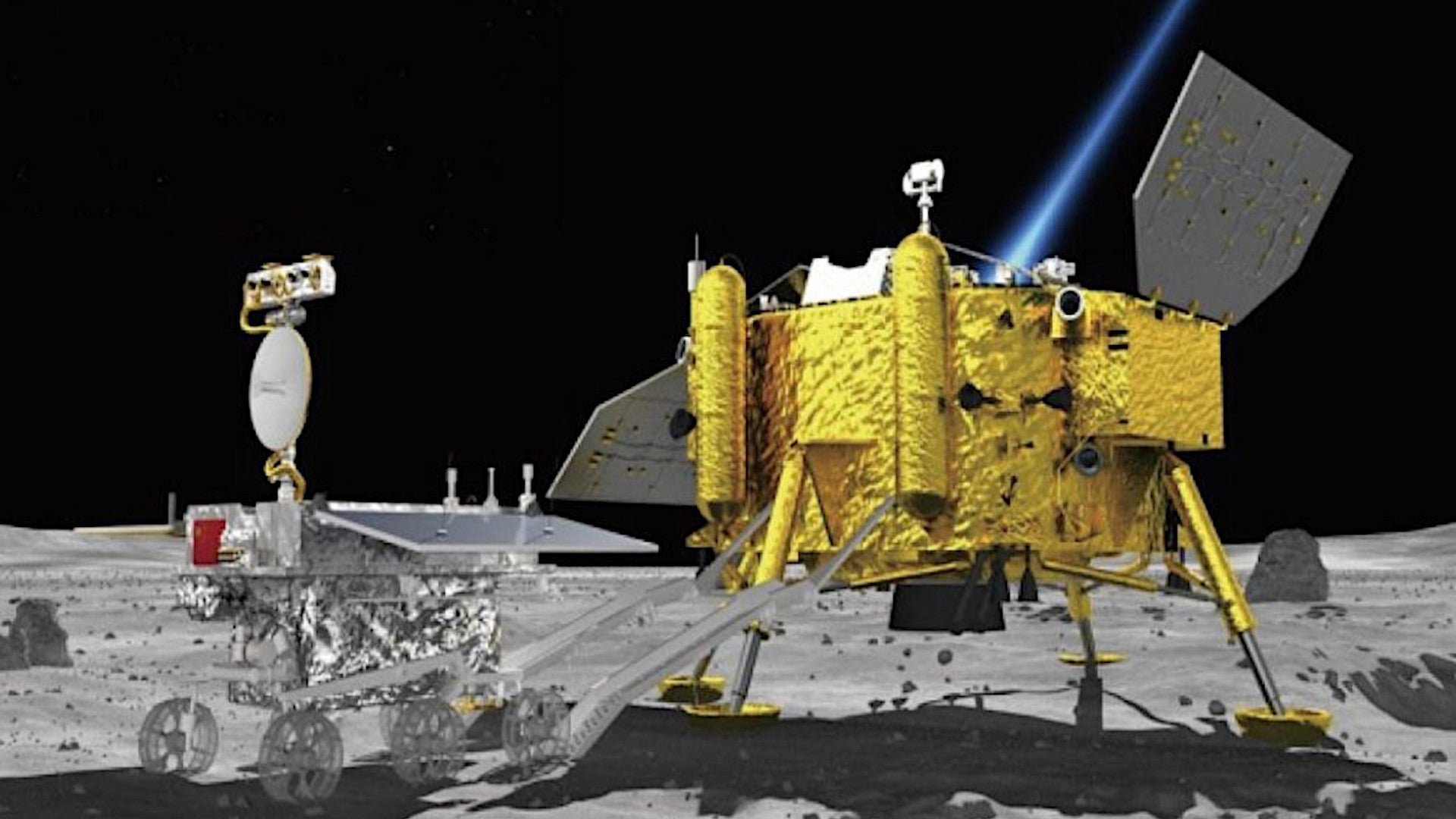

The lander itself has various cameras, a spectrometer, and a neutron dosimeter in order to gather scientific data. It has also deployed a mobile rover weighing more than 300 pounds that carries its own electro-optical systems, spectrometer, energetic neutral atom analyzer, and ground-penetrating radar.

The Chang’e 4’s primary mission is to study geophysics and radiation characteristics of the far side of the Moon, as well as peer out into deep space. Due to a situation called “tidal locking,” the dark side never faces the Earth, giving it unique characteristics.

“Since the far side of the moon is shielded from electromagnetic interference from the Earth, it’s an ideal place to research the space environment and solar bursts,” Tongjie Liu, the deputy director of the Lunar Exploration and Space Program Center at the China National Space Administration, explained, according to CNN. “The probe can ‘listen’ to the deeper reaches of the cosmos.”

While the information the lander and its rover are set to gather could be of high scientific value, just getting the spacecraft to the far side of the moon was an achievement in of itself. Since there is no direct line-of-sight to Earth, the Chinese can only communicate with Chang’e 4 via a dedicated communications relay satellite, known as Queqiao.

The team at CNSA overseeing the mission spent much of the time between when the spacecraft arrived in orbit around the Moon on Dec. 12 and when it finally set down on the lunar surface four weeks later ensuring that these data links worked as intended. Chang’e 4’s landing itself was entirely autonomous.

The potential risks and associated costs have long stood in the way of a mission to the dark side of the Moon. U.S. astronaut Harrison Schmitt had proposed that the Apollo 17 mission, the United States’ last manned lunar mission, head to the far side using a satellite relay arrangement. NASA rejected the idea.

Chang’e 4 is also the latest in the Chang’e series, all of which have been stepping stones toward China’s plans for a manned lunar mission and the potential construction of a semi-permeant outpost on the Moon as part of the overarching Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP). The present mission’s scientific research will support studies into the practicality of sending actual humans to the dark side of the moon and potentially leaving them there for protracted periods of time.

In addition to its various sensors and data collection systems, the lander also has a self-contained “biosphere” with various seeds and silkworm eggs. Chinese scientists are interested to know whether the plants and insects can create a sustaining, symbiotic relationship inside the artificial habitat.

The future Chang’e 5 and 6 missions’ goals are to conduct round trips to the Moon where the semi-autonomous craft comes back to earth. This will set the stage for the actual manned operation, set to occur sometime in the 2030s. The European Space Agency (ESA) has indicated it might be interested in working together with China on the CLEP program.

There is great hope that new manned missions to the Moon, and a potential base there, will further humanity’s understanding of the moon and space in general. At the same time, there are concerns that China may have more ambitious designs and that these missions could have a military component.

“China has been very clear in its understanding of this. They have compared the moon to the South China Sea and Taiwan, and asteroids to the East China Sea,” Malcolm Davis, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, told The Guardian. “They’re making a very clear geopolitical comparison with what’s happening with space and we need to pay attention to that.”

In recent years, China has become increasingly assertive of its expansive terrestrial claims, especially in the South China Sea, using a constellation of militarized man-made islands to try to force other countries out of the region. A lunar outpost might similarly give the Chinese a very tangible and unprecedented national claim to a portion of the Moon’s surface. Though there is no agreement about whether it will ever be practical to extract natural resources to exploit on the Moon, as well as asteroids further out in space, or what regulations might apply, China’s lunar missions could give it a leg up in any such future endeavors.

In October 2018, Jeff Gossel, the top intelligence engineer within the U.S. Air Force’s National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s (NASIC) Space and Missile Analysis Group warned about the potential for a more nefarious purpose to the Queqiao relay satellite specifically. Though he noted that the likelihood of the threat remained small, the engineer described a nonetheless worrying theoretical possibility that the Chinese could the dark side of the Moon to hide anti-satellite weapons.

“You could fly some sort of a weapon around the moon and it comes back — it could literally come at [objects] in GEO [geosynchronous orbit],” he explained at an Air Force Association gathering on Oct. 12, 2018. “And we would never know because there is nothing watching in that direction.”

Any spacecraft that can semi-autonomously travel to the dark side of the moon and then launch back toward Earth on command unannounced would also have a distinct potential as a space-based weapon. Since the dark side of the moon is difficult to monitor from Earth and space in general, it could be hard to independently confirm whether or not a Chinese outpost there is exclusively scientific in nature in general.

International treaties presently ban the deployment of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction in space or on the Moon, but do not prohibit conventional types or dual-use systems. This has already caused significant consternation between the United States and Russia over the exact purpose of Russia’s “space apparatus inspectors.”

The U.S. government contends that these small, highly maneuverable satellites, which you can read about in more detail here, are inherently dual-purpose and give the Kremlin a cover story for fielding space-based weapons. Russia also has a variety of ground-based and air-launched anti-satellite weapons in various stages of development. The Chinese have also demonstrated a terrestrial anti-satellite capability and continue to invest in these weapons.

All of these developments are meant to challenge to the advantages America has long enjoyed through its military space assets tasked with early warning, intelligence gathering, navigation and weapons guidance, and communications. We at The War Zone

have continually highlighted these growing threats to the U.S. military’s space-based capabilities.

All said, Chang’e 4’s mission to the dark side of the Moon is certainly a major achievement for the CNSA and will hopefully provide important benefits for space research. But it may also presage an all-new front in the steadily evolving nature of military activities in space.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com