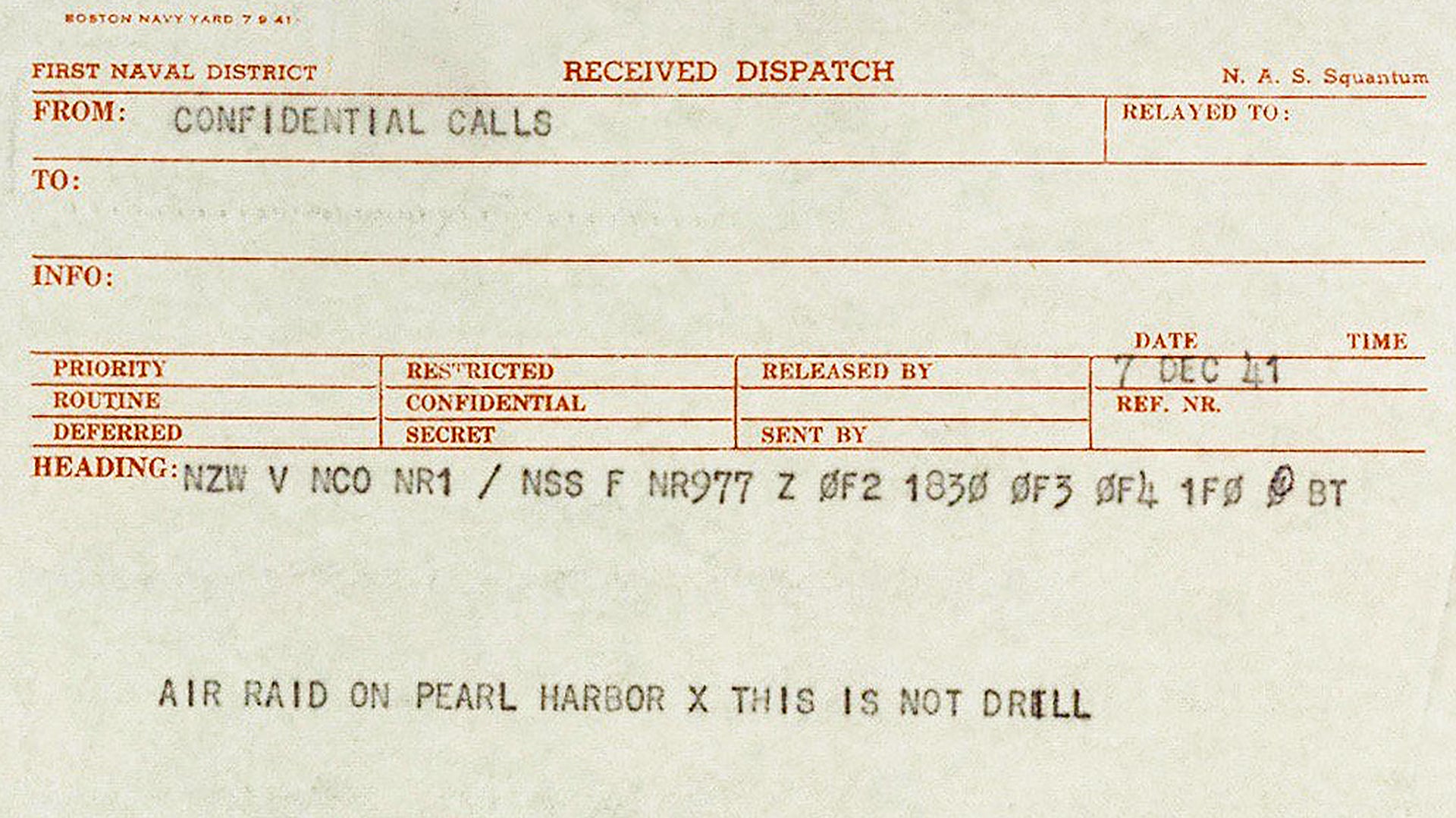

The message above was sent by the office of the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet just minutes after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor began. It went out to ships and naval stations throughout the Pacific region and word of it quickly spread beyond. It was the first official correspondence acknowledging an event that would change the course of history in so many ways—one that still hangs over strategic decision making and national security policy to this very day.

The telegram was sent at 7:58am on December 7th, 1941 by Lieutenant Commander Logan Ramsey who had just witnessed first-hand low-flying airplanes with big red meatballs on their sides attacking Ford Island. The message informed Navy vessels of the attack, including the carriers that, by a stroke of sheer luck, were out at sea that fateful day and were spared from the onslaught of Yamamoto’s planned waves of aerial bombardment on the strategic American outpost in the Pacific.

For two hours and 20 minutes, beginning at 7:55am, Pearl Harbor was bombarded and strafed by Japanese aircraft. In all, 2,403 people on the American side were killed, 55 Japanese also perished in the operation, and 21 ships and 300 aircraft were damaged or entirely destroyed.

It was a horrendous blow military to the United States, but even more so psychologically. The U.S. could no longer avoid wading into the maelstrom that we now call World War II. The next day, President Roosevelt declared war on Japan and a formal congressional declaration of war against all the Axis Powers would follow three days later.

The House of Representatives historical webpage describes how these declarations occurred in the following passage:

On this date, the House approved declarations of war against Axis Powers Germany and Italy—just three days after Congress had declared war against Japan. On the morning of December 11, during a rambling speech at the German Reichstag, Adolph Hitler declared war on the United States in accord with the Tripartite Pact of September 27, 1940; Italy followed suit.

President Roosevelt’s swift rejoinder requesting a declaration of war against both Axis nations was read to the House by reading clerk Irving Swanson. “The forces endeavoring to enslave the entire world now are moving toward this hemisphere,” Roosevelt wrote. “Rapid and united effort by all of the peoples of the world who are determined to remain free will ensure a world victory of the forces of justice and of righteousness over the forces of savagery and of barbarism.” The House first adopted the war resolution against Germany 393–0, followed moments later by a 399–0 vote to declare war on Italy.

In both instances, Jeannette Rankin of Montana, who had voted against the declaration of war on Japan, answered “Present.” Shortly afterward, Frances Bolton of Ohio, who had earlier opposed U.S. intervention in the European conflict, summed up congressional resolve as isolationist sentiment melted away. Bolton told colleagues, “all that is passed. We are at war and there is no place in our lives for anything that will not build up our strength and power, and build it quickly.” After the conclusion of the session, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn of Texas presented the gavel to reading clerk Swanson in appreciation for having read Roosevelt’s message and taken the roll calls. That gavel is now on display in the Capitol Visitor Center.

Often times, there is confusion about the first communique from the attack on Pearl Harbor as it appears on multiple letterheads and in various formats, but that is because those documents are receipts of the message that was transmitted to many locales and ships. For instance, the carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) was on her way to Midway to deliver Marine fighter aircraft when the message came through. The ship’s Executive Officer Wallace “Gotch” Dillon was first to see it come through the teletype machine. This is that version of the message:

Nearly 12 hours later, the Lexington received an official message that she should be ready to intercept the Japanese fleet and avenge the attack. This would likely have been a suicide mission, but the order to execute that mission never came.

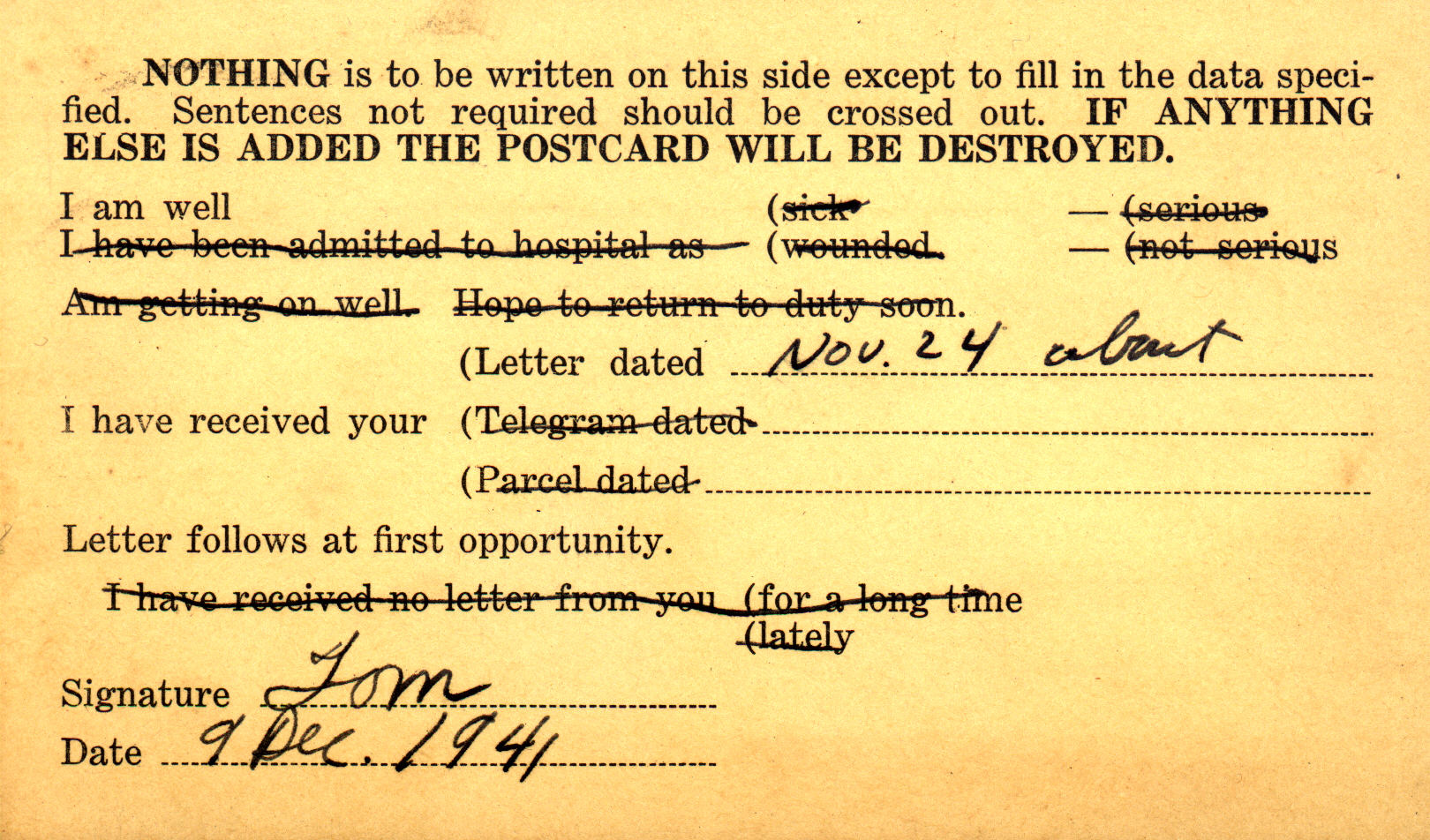

Other messages that emanated throughout the day from Oahu were many in number and highly inaccurate due to the fog of war and the very real sense that an invasion of the islands was imminent. In the days after the attack, with security now at its highest state on the smoldering paradise-like island, personnel trying just to get word home that they survived the raid became an exercise in extreme message control and brevity. This is an example of the postcards that servicemembers were allowed to send home to let loved ones know that they had survived the attack:

Today, 77 years after that horrible day, text messaging is once again a primary form of communication, although our variation of it is far more nimble than the kind our forebearers were using during World War II. But that doesn’t mean it can’t have just as large an impact, in fact, it can be even more impactful due to its widely distributed nature and near instantaneous delivery. This was demonstrated to a disastrous degree recently in the Hawaiian Islands of all places when the government sent out an alert to the population saying a ballistic missile strike was imminent. Chaos, confusion, fear, and eventually anger ensued. Now the President of The United States has their own direct emergency text service via FEMA at their disposal as well.

With all this in mind, it’s a bit bewildering to think that 77 years after “the date that will live in infamy,” God forbid there is another attack on the United States, or any other large-scale national emergency, we will probably hear about it first via text message as well.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com