The U.S. Army has taken an important step toward the establishment of its first operational hypersonic missile unit with the delivery of two inert canisters for training purposes. These canisters are of the exact same design of the ones that will eventually hold live examples service’s Long Range Hypersonic Weapon, or LRHW, and will give troops an opportunity to begin practicing handling them as they would during real operations.

The Pentagon released pictures of the pair of canisters on March 17, 2021, but the metadata says that they were taken on March 10. Army Lieutenant General L. Neil Thurgood, head of the Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office, had said in an interview with Defense News in February that he would personally oversee the delivery of these training aids on March 8.

“Later in 2021, the Army will deliver all additional ground equipment for the Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) prototype battery,” according to a generic caption accompanying all of the pictures of the delivery of the training canisters. “LRHW battery fielding will complete in Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 with the delivery of live missile rounds.”

The Army has not yet disclosed the official nomenclature of this initial LRHW unit or even where it is based. The pictures of the delivery of the training canisters only say that they were taken inside the United States. The heavy secrecy surrounding the establishment of this battery is further underscored by the fact that none of the individuals seen in the photographs are wearing unit patches and some of them do not even have name tapes on their uniforms.

It is slightly difficult to read, but it appears that the sides of canisters say that they weigh 20,500 pounds “loaded” and 4,200 pounds “spent.” This could indicate that the LRHW itself is around 16,300 pounds.

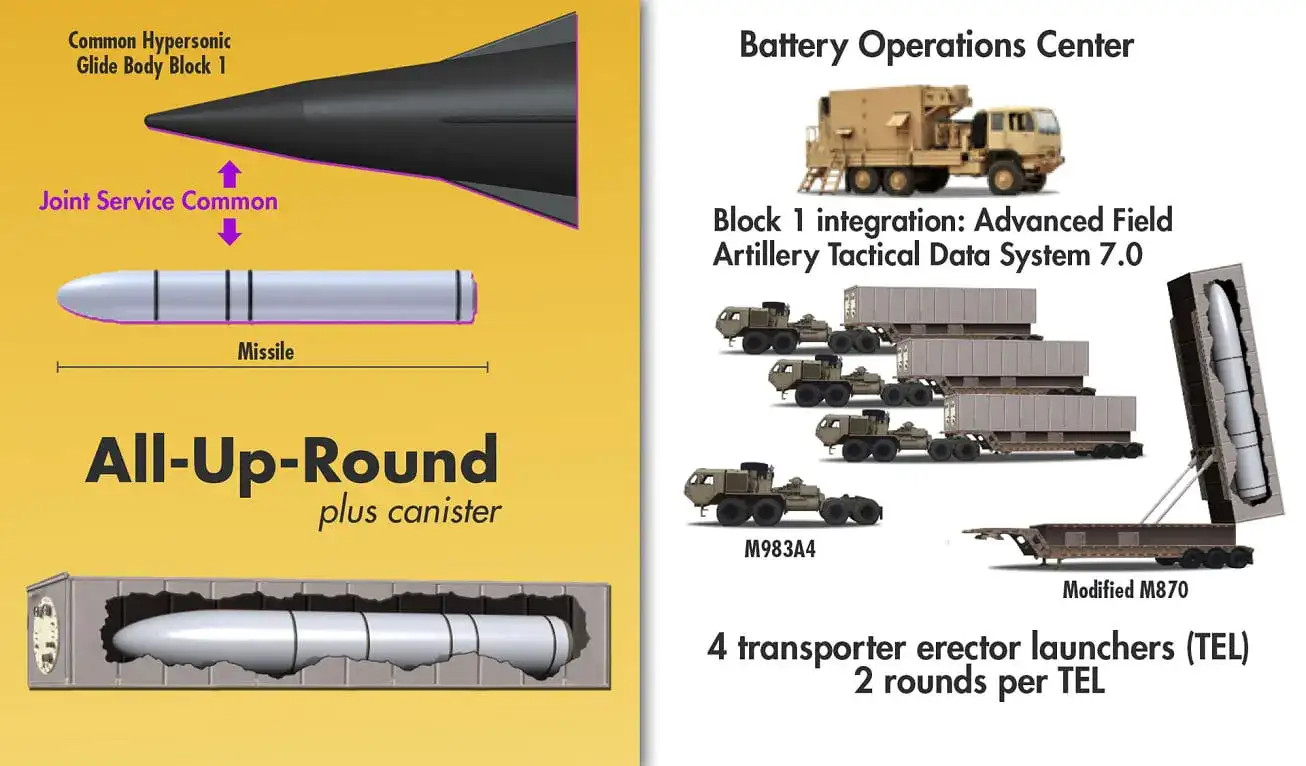

Regardless, the arrival of these canisters is an important achievement and puts the Army just one step closer to fielding the LRHW, which is set to be its first operational hypersonic weapon, not counting more conventional ballistic missiles that were phased out decades ago. The service has been developing the LRHW as part of a joint-service effort with the U.S. Navy. The designs of the Army’s missile and the Navy’s Intermediate-Range Conventional Prompt Strike (IRCPS) weapon are effectively identical, though the launch canisters they will sit in will be different, and they will both be tipped with the same conical unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle, also known as the Common Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB).

The compete LRHW and IRCPS weapons both use large rocket boost to loft the C-HGB to an optimal speed and altitude. After that, the vehicle glides back down toward its target along a relatively level flight trajectory at hypersonic speeds, which are defined as anything above Mach 5. The Pentagon has previously said that the C-HGB will be able to “strike targets hundreds and even thousands of miles away” and reach a peak speed of Mach 17.

The combination of this speed together with the vehicle’s ability to make more unpredictable movements, compared to traditional ballistic missiles, while following a largely atmospheric flight profile, make hypersonic weapons extremely hard, at best, to defend against and makes it difficult for an opponent to otherwise respond to incoming strikes, either by relocating critical assets or otherwise seeking cover. The LRHW promises to give the Army “a new capability that provides a unique combination of speed, maneuverability, and altitude to defeat time-critical, heavily-defended and high value targets,” according to the captions on the pictures of the delivery of the training canisters.

Dynetics, part of the Lockheed Martin-led team developing both of these weapons, has been in charge of the C-HGB design, which is derived from work previously conducted by the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratories. Defense News reported that this the first hypersonic boost-glide vehicle to be produced entirely within the U.S. industrial base, rather than in part at U.S. government facilities. You can read more about the earlier Sandia Winged Energetic Reentry Vehicle Experiment (SWERVE) and the initial phases of this joint-service project, which the Air Force was also involved in until it dropped out last year, in this past War Zone story.

“Transitioning production technology is not as easy as people might perceive it to be,” Lieutenant General Thurgood, the Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office boss, had told Defense News earlier this year. “Production, especially high-end production, is part engineering and part art; and so the engineering piece you can learn through drawings and those kind of things, but the art of it is always the hardest part, so that’s why we chose an in-person, face-to-face, leader-follower [strategy] — that institutional knowledge that everybody has in every profession that’s never written down.”

Flight tests of the C-HGB have already occurred, but joint Army-Navy testing of actual prototype LRHW/IRCPS missiles is only set to begin this year. However, the Army’s prototype battery is not set to take part in any such tests until the 2022 Fiscal Year.

This makes the canisters all the more important since it will give soldiers a way to begin getting a certain amount of hands-on training now ahead of those tests. The additional equipment that the prototype battery is scheduled to receive this year will likely include the trailer-mounted launchers for the missiles, as well as other equipment needed for the unit to be able to go through all of the procedures that would be involved in the actual employment of the missiles. Defense News had reported that the canisters, among other equipment, would be used for what it described as “end-to-end kill chain training.”

All of this is made more important given that the Army hopes that the prototype battery will provide at least a limited operational capability when it is fully established, a process that it expects to complete in the 2023 Fiscal Year. At that point, the unit might also begin taking part in exercises as the service explores how it will integrate these capabilities in future operations, including those with elements from other branches of the U.S. military, as well as foreign allies and partners.

New ground-based long-strike capabilities, including hypersonic weapons, are a notably important component of a strategy U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) has proposed for containing China in the Western Pacific region. You can read more about what is known now about the Pacific Deterrence Initiative in this past War Zone piece.

All told, it may seem like a relatively small thing, but the delivery of these training canisters is a big step for the Army toward making its hypersonic weapons plans a reality.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com