There is a lot of soaring rhetoric filled with grand hopes and dreams when it comes to achieving a 355 ship U.S. Navy fleet in the coming decades, but it’s clear that the sea going service will have a much harder time finding a way to reach that goal than many would like to believe. Tough decisions that are critical to realizing a larger naval end strength, some of which include breaking with decades of established habits, many of which run counter to massive shipbuilding special interest influences, are fast approaching, or in some cases, they have already come and gone.

At every turn there is a risk and reward proposition, but the idea that the Navy will build its way to its 355 ship goal alone is a losing mindset that serves to satisfy the shipbuilding special interests and the Pentagon’s obsession with obtaining new platforms at great cost over affordably updating the ones it already owns. Also, this grand wish for a 355 ship fleet—it has about 275 ships today—sits against the harsh reality that the Navy is already tired and fractured.

The fact that in the span of a handful of months the service had put two major surface combatants out of action and lost many lives in the process due to its own systemic failings underlines this truth. But just the Navy’s near-term procurement and force structure choices for its surface combatant fleet alone can make or break the prospects of achieving its grand goal, notwithstanding the many other issues it currently faces.

Tico Twilight?

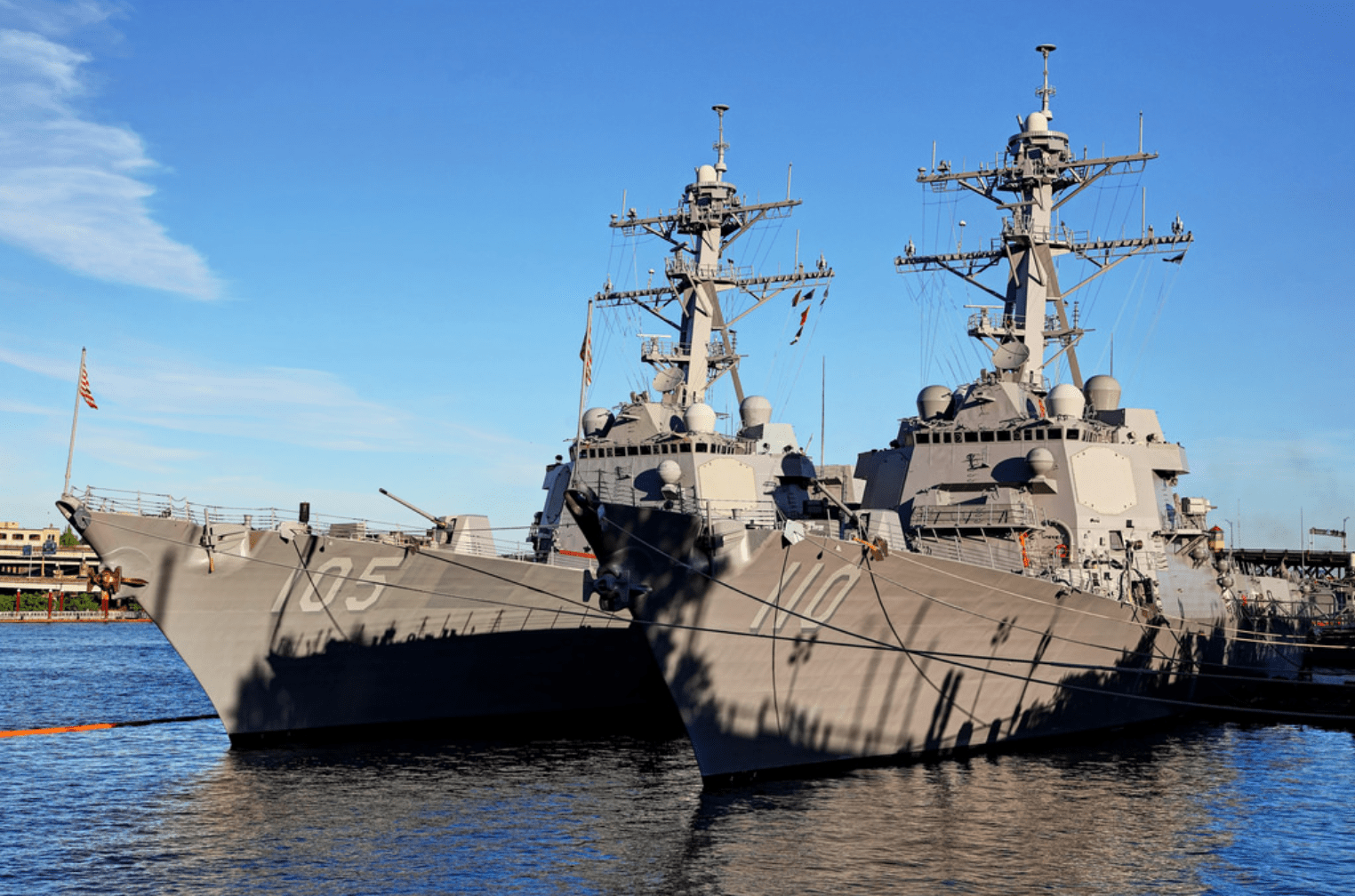

One of the most critical conundrums facing the Navy and its future force structure objectives is what to do with its aging Ticonderoga class cruisers. These vessels offer command and control and weapons capacity that their increasingly complex Arleigh Burke class destroyer counterparts don’t. The oldest eleven of these ships—half of the active cruiser fleet—are approaching the end of their predetermined service lives and are slated to be decommissioned at a rate of two per year starting in 2020. But with some upgrade and sustainment dollars they could continue to provide a unique set of highly important capabilities for many years to come.

By most accounts there is indeed a lot of life left in these vessels, but everything from the ships’ increasingly finicky and maintenance intensive SPY-1 radar to their piping and mechanical systems would need TLC or replacement in order to realize an extended service life. The vessel’s radar in particular needs a major upgrade to keep it not only viable, but even reliable on any level if the ships are to remain in the fleet.

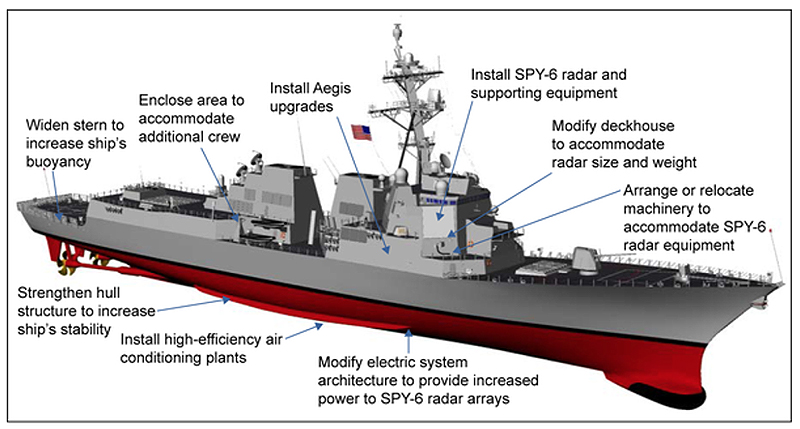

There is no easy answer to this issue as the radar cannot be swapped out for the far heavier SPY-6 air and missile defense radar (AMDR) that is slated to outfit the Navy’s upcoming super-sized variant of its Arleigh Burke class destroyers. Nearly half of the Arleigh Burke class design is being redesigned to accommodate this new, larger, solid-state radar system, making it almost an entirely new class of ship onto itself. The Ticonderoga class and its already overloaded hull and cracking aluminum superstructure won’t benefit from the luxury of such an elaborate redesign.

Some have suggested going for the truncated version of the SPY-6 that could find itself on a future U.S. Navy frigate, but equipping a mighty cruiser with a similar radar system as what may soon be found on a frigate doesn’t sound too attractive even though it would likely be a major step up in some capability areas over the troublesome phased arrays currently fitted.

Regardless of what format a Ticonderoga class upgrade would take, the biggest challenge will be getting the funding to make those upgrades a reality. It seems like the Navy and congress all agree that they need to extend the service life of these ships, but at the same time getting the money set aside to do so soon will likely remain a major challenge.

There is also the issue that any comprehensive life extension initiative for these ships will eat into shipbuilding funds and could impact other priorities. And just getting upgrades and refits scheduled will be increasingly challenging as these ships creep toward retirement and their condition continues to deteriorate. Without clear planning, these vessels could end up being sidelined due to backlogs of other naval work and as long-lead items needed for their upgrades are procured. All this could make them even less attractive for a life extension program as time moves on, thus making the Navy’s 355 ship goal even less attainable.

Burke Block Buy?

The backbone of the proposed 355 ship U.S. Navy fleet will be the Arleigh Burke class destroyer in its multiple forms. The next generation Arleigh Burke class design, known as the Flight III configuration, borders on an entirely new class. As we mentioned earlier, nearly half the ship has been redesigned. This includes major changes to its hull-form and its superstructure. Many of these changes were made to accommodate the solid-state SPY-6 AMDR radar arrays, which are larger and feature a far denser weight distribution than their predecessors. The ship also features a hybrid-electric drive system and other improvements.

The advent of the Flight III configuration is at least partially the result of the drastically curtailed DDG-1000 Zumwalt class destroyer program that was the victim of chronic cost cutting and dwindling capabilities requirements throughout its decade long design phase. You can read all about this travesty in this past feature. With the first of the Flight III Burkes slated to be delivered in 2023, the big question facing the Navy and Congress is whether or not to do a block buy of 10 ships to hopefully lower the type’s unit price. Basically, buying 10 of these totally unproven vessels will supposedly save 10 percent. So basically buy 10 ships and get one free.

The problem with this is that the design, although based on the proven Flight IIA Arleigh Burke class, is largely new, as are many of its sub-systems, so putting 10 ships into production, each costing billions of dollars, without even testing a prototype first could result in a procurement disaster. The practice of putting something into production before testing it—or even finishing designing it—is called concurrency and it has plagued other high profile programs in recent years, like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, Littoral Combat Ship, and Ford class supercarrier.

The Navy says that the entire ship is designed in a 3D virtual environment down to the nuts and bolts, which sounds impressive, but we have heard that type of claim before and the outcome wasn’t all that rosy. Many worry that even with a good design compiled via the best CAD tools available it still doesn’t mean the shipyard or the Navy knows exactly what one of these ships will cost until they actually build one. If 10 are bought at one time, savings could be left on the table or the overruns could be massive.

Defense News quoted Bryan McGrath, a retired destroyer captain and consultant with The Ferrybridge Group about the bulk buy and its drawbacks:

“Everyone is just sort of guessing what it will cost… When the shipyards are bidding on a multiyear on a design that includes as much immaturity as this one does, they have to price that risk… One outcome is they overprice the risk and the taxpayers pay, or they underprice the risk and the taxpayers pay, or they get it right. But the reality is that these sort of risk calculations are difficult to get right… I am a big believer in the Flight III DDG and the direction it’s going, but the differences between it and the IIA are considerable. Substantial enough to warrant prudence, and that to me means each shipyard building at least a number of these successfully before we go to a multiyear procurement… I can see a day where we have the DDG 51 program manager and the assistant secretary of the Navy for research and development called before the SASC, six to 10 years from now to answer for cost overruns that were wholly foreseeable given the risk of moving from a IIA to a Flight III.”

One option may be to continue building Flight IIAs, which are still in production, while the first pair of Flight III ships are being tested, and then begin high-rate production of Flight III ships via a bulk buy once the design hasn’t finished testing. This won’t deliver new capabilities to the fleet as fast as the concurrency route, but it will keep the production line warm, drastically lower risk, and it would allow for small improvements to the Flight III design to be made before buying the ships in bulk.

If this approach isn’t taken, and the Flight III ships run into major development issues while under bulk concurrent production and testing, it could cause a logjam in the shipyards that would impact the Navy’s dream of a 355 ship fleet significantly.

Passing On The Perrys?

One of these critical decisions that seems to have already been made concerns what the Navy plans to do with its mothballed fleet of Oliver Hazard Perry class (FFG-7) frigates. It was originally thought that the Navy could economically upgrade these vessels in a similar fashion as allied nations have, some of which have taken the surplus fighting ships and modernized their combat systems and weaponry. That idea was quickly jettisoned by the Navy’s brass. Then the 10 frigates—or the best seven of the lot—were being eyed for regeneration with nearly no upgrades at all. The idea was to deliver them “navigation and radar ready” multi-functional functional platforms.

These vessels would execute low-end missions in low-threat environments, such as counter-narcotics missions and anti-piracy operations. This would allow higher-end ships to be freed up for more complex and demanding missions.

Very recently the Navy swatted down this idea as well due to costs—a claim that is dubious at best upon closer review. The Navy has since officially obligated Littoral Combat Ships and Spearhead class logistical vessels to the counter-narcotics mission in the coming years.

This decision seems like a big glaring missed opportunity. At the very least the seven best FFG-7 hulls could have been returned to the fleet to help the Navy reach its 355 ship goal, and it’s not like they aren’t going to commit existing resources to what would have been the regenerated Perry class’s intended mission sets.

Fresh Frigate Hope?

An all new frigate—something many of us have been desperately pleading for for years—could be key in offsetting these and other hurdles the Navy will face on its journey to realize a 355 ship navy. Now known officially as the FFG(X), this program aims to step in partially where the Littoral Combat Ship program failed and bring additional higher-end capabilities to table.

The type could go a long way in providing multi-role capabilities that would take the pressure off of the Navy’s over-tasked destroyer fleet, freeing those ships up for more demanding missions. If this vessel can be produced relatively quickly, in significant numbers, and comparatively cheaply, the Navy could even decide to trade a bit of its future high-end combat power for a bit more middle-end combat power.

This new frigate, which is due to hit the water in 2023, as is the Flight III Arleigh Burke class destroyer, with the Navy evaluating sensors, weapons, and hull designs now. The ship will be highly capable of “blue water” operations far out to sea for extended periods of time as part of a larger networked surface action group, carrier strike group, or expeditionary strike group, or independently.

The ship will also be capable of surviving in higher threat environments, something the Littoral Combat Ship stands little chance of doing. Area air defense with at least the capability to employ RIM-166 Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles is a given, as well as an over the horizon anti-surface and strike capability. Basically we are talking about a real fighting ship that will create a new bridge between the anemic and single mission-focused Littoral Combat Ship and the mighty Arleigh Burke class destroyer.

Hope Float On A Good Plan And A Steady Stream Of Dollars.

Regardless of any of these choices, the Navy’s big goal is predicated on having a reliable defense budget. You can have the best plan imaginable to achieve a 355 ship Navy, but if the dollars are always in limbo, that stellar plan can become its own nightmare. But still, at least having a comprehensive plan would help guide funding in a positive way, show that the goal is indeed attainable, and to build broad support for it, but so far the Navy still hasn’t produced one.

One positive sign would be if at least some sort of real priority would be placed on using the assets the Navy already owns to help in achieving its goal instead of being so highly focused on procuring expensive new vessels. Passing over the Oliver Hazard Perry class seems like more of the same for Navy, not a creative new way forward, and securing the future of the 11 oldest Ticonderoga class cruisers now seems like an absolutely essential initiative, not just to help reach the 355 ship goal, but also for overall national security in the near term.

In fact, those cruisers act as a sort of “canary in the coal mine” from which to gauge the plausibility that the Navy and congress can get their acts together enough to have any shot at achieving the 355 ship goal. If they can’t smoothly save those ships from being sidelined or mothballed, than there is little hope that such a large fleet will ever come to pass.

As for block buys of Flight III Arleigh Burke class destroyers, the Navy would be better off continuing production of the current Flight IIA design and testing the first examples of the Flight III design thoroughly before committing to a block purchase worth tens of billions of dollars. And once again, the wild card when it comes to the Navy’s surface combatant fleet is the FFG(X). It looks like the Navy has finally come to its senses as far as what it needs in this class of ship, and it could just prove to be so capable for the money that a few less destroyers will be needed down the line.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com