Despite recent reports that the U.S. Navy could abandon the effort altogether, the service has included millions of dollars in its latest budget request to continue working on its potentially game-changing railgun. Though overall funds for the project have fluctuated in recent years, the revelation that the Chinese may have installed their own prototype weapon on an actual ship could prompt the service and Congress to try and accelerate the electromagnetic cannon’s development.

On Feb. 12, 2018, the Navy released its proposed budget for the 2019 fiscal year, which allots almost $45.8 million for research and development into both electromagnetic and directed energy weapons, reflecting the latest phase in the project’s evolution. This is a common pool that pays for the railgun project, as well as work on maturing solid state laser technology and a joint program with the U.S. Air Force to build a high-powered radio frequency weapon for aircraft called High-power Joint Electromagnetic Non-Kinetic Strike (HIJENKS).

Though the new budget proposal calls for more than $10 million less than the service asked for in the previous fiscal cycle, the documents are clear that the service remains committed to the electromagnetic weapon. The funding, in part, will go toward “development addressing the unique technical challenges inherent in the construction, assembly and operation of a high-power, kinetic energy weapon prototype capable of repeatedly launching long range, precision guided projectiles using electricity instead of chemical propellants,” the official description says.

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) has been working steadily on the railgun since 2005 and has procured two separate prototypes from BAE Systems and General Atomics. In 2012, the Navy pushed hard to move things along from a technology demonstration to a formal program of record to buy actual electromagnetic cannons.

“What I’m finding is if I go ahead with the demo it will slow my development,” U.S. Navy Admiral Pete Fanta, then the director of surface warfare and now the head of warfare integration, told Defense News in 2016. “I would rather get an operational unit out there faster than do a demonstration that just does a demonstration.”

As we at the War Zone have noted before, this seemed like an odd course of action given the U.S. Navy’s own experiences with similar efforts to “concurrently” develop and produce other high-tech systems, many of which remain mired in controversy. Not surprisingly, that aggressive strategy did not produce the desired results and in its budget for the 2018 fiscal year, the service smartly refocused its efforts on the research and development aspect of the project, pushing off an at-sea test until at least 2019. The railgun and various other technologies ended up in an all new budget line called “Innovative Naval Prototypes.”

“These investments represent game-changing technologies with the potential to revolutionize operational concepts,” the Navy says in its broad description of programs that fall into this category. “They are disruptive in nature as they would dramatically change the way naval forces fight.”

With regards to the railgun, it’s hard to overstate just how impressive such a weapon could be if engineers can turn the technology into a functional and cost-effective system. At their most basic, railguns rely on a series of electromagnets to shoot a projectile at hypersonic speeds. In most cases, the round lies on sheer velocity to destroy its target rather than an explosive charge.

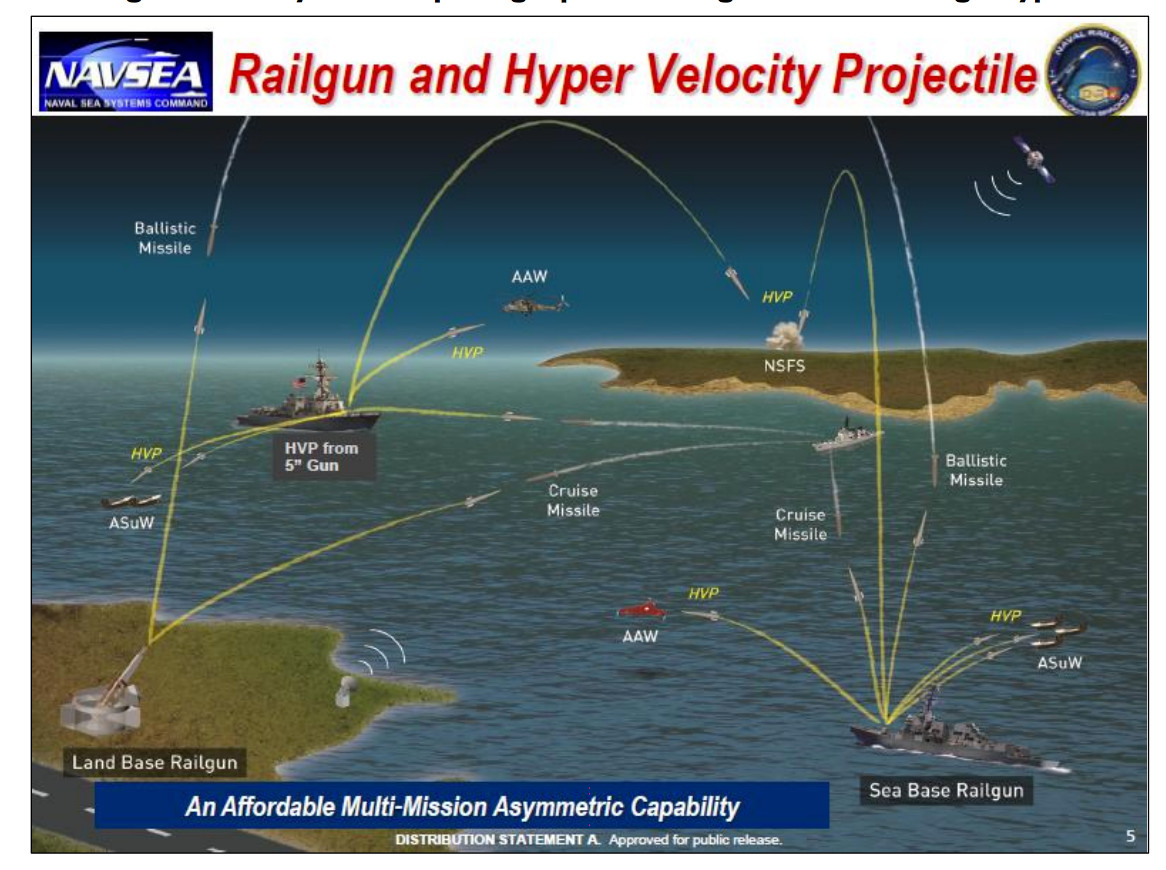

The Navy says its existing prototype can launch rounds at over 4,500 miles per hour, or around six times the speed of sound. The final design could have a range of more than 100 miles. An operational weapon with similar characteristics might be able to engage a variety of targets rapidly in both offensive and defensive scenarios, including striking targets on land and at sea and shooting down enemy aircraft and incoming cruise missiles and maybe even ballistic missiles, which you can read about in more detail here.

This is a multi-mission capability far beyond what the five-inch guns on the service’s existing Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Arleigh Burke-class destroyers can achieve. Those weapons fire shells at less than half the speed of the Navy’s prototype railgun even with the largest propellant charges available.

And the railgun doesn’t require any chemical propellant at all. As such, an operational weapon could give ships more magazine depth, free up space for additional systems, and might reduce various logistics costs over time.

It’s true that the overall funding for the railgun project has seen a downward trend in recent years. In its budget proposal for the 2015 fiscal year, the service asked for nearly $47 million just for the railgun. This was down to less than $20 million two years later and there have since been reports that the Navy might be looking for a way to kill off the project entirely.

But without knowing the exact rationale behind those fluctuations or the exact fiscal requirements needed to reach the program’s goals during those years, it’s impossible to say that this actually reflects a change in the Navy’s commitment to the revolutionary technology. Deferring the at-sea test would have significantly changed the budget outlay by itself without necessarily having an impact on other parts of the research and development effort. Relatively small, high-tech projects like the railgun program often have non-linear budgets to begin with on account of the need for protracted test cycles interspersed with bursts of new developments.

And the Navy has worked hard to broaden the appeal of the effort by separating out the projectile portion and working to develop a High Velocity Projectile (HVP) that would work in both the railgun and conventional cannons. The service says the streamlined design should still be able to reach Mach 3 with a chemical propellent charge, much faster than traditional rounds. Since these inert shells would work in railguns, naval guns, and U.S. Army and Marine Corps howitzers, it could also help share the cost burden of development, as well as expanding the capabilities of existing weapons in the near term.

The reality of electromagnetic weapons might be getting too hard for the Navy or other the rest of the U.S. military not to prioritize, anyways. In January 2018, images emerged of what is very likely a Chinese prototype railgun on a test ship. We don’t know how functional this system might be, but it could put the Chinese ahead of its American counterparts in demonstrating a realistic capability in this regard.

Chinese developments in the realm of hypersonic weapons broadly, including both electromagnetic cannons and hypersonic boost glide vehicles and missiles, have already been significant. It only reinforces what we at The War Zone and others have been warning about when it comes to China’s rapidly expanding advanced weapons development programs, as well as its ability to actually field many of those systems. All of this in support of the country’s desire to continue moving from a regional power to major player on the international stage.

“We need to continue to pursue that [technology] in a most aggressive way,” U.S. Navy Admiral Harry Harris, in charge of all American military operations across the Pacific, told members of the House Armed Services Committee on Feb. 14, 2017. “[We must] develop our own hypersonic offensive weapons.”

The Navy had likely firmed up most of its latest request well before the Chinese revealed their own apparent prototype railgun, but many senior officials and legislators share Harris’ views already. This might lead lawmakers to try and plus up the Navy’s budget when it comes to the railgun project, as well as funding for other hypersonic weapons and defenses across the U.S. military.

Regardless, China’s developments are only unlikely to underscore the long-standing service’s desire to put even a prototype system on board a ship as soon as possible. Depending on how eager the Navy and its supporters in Congress are, and how mature the technology actually is at present, we may see a surge in railgun developments in future budgets, and possibly even before then.

One thing is clear, the Navy isn’t throwing out its railgun anytime soon.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com