The U.S. Navy is reportedly seeking to delay critical shock testing of its newest aircraft carrier, the USS Gerald R. Ford, which is essential for determining whether the ship is ready for combat, for up to six years. That news follows a damning Pentagon report that shows the vessel’s essential systems, such as its electromagnetic catapults, new arresting gear, and advanced radar, still don’t work right under the best conditions.

On Feb. 7, 2018, Bloomberg revealed that the Navy had appealed directly to Secretary of Defense James Mattis to sign off on delaying the shock testing, which involves setting off large explosive charges near a ship with a representative crew on board and seeing how the vessel holds up, to 2024. Those discussions revolve around the service’s desire to remove funding for the trials in their draft budget request for the 2019 fiscal year. That plan would see the shock tests performed some time in 2019.

“Secretary Mattis will respond directly to the Navy when he makes a decision,” was all Pentagon spokesperson U.S. Navy Commander Patrick Evans would tell Bloomberg about the deliberations. U.S. Navy Captain Danny Hernandez, a public affairs officer for the service specifically, simply told the outlet that the discussions were ongoing.

The Navy’s shock testing, or formally the Full Ship Shock Trial (FSST), isn’t supposed to harm the vessel or anyone on board, but rather to rattle everything to see if sensitive systems or other design features might be particularly vulnerable. If problems, or any actual damage or injuries, do occur it’s would be a pretty clear sign that there’s still work to be done before sending the ship out for potentially real combat missions.

The Navy is supposed to put all new warship designs through the FSST process. This requirement has been slipping in recent years, though, with the service commissioning a number of Littoral Combat Ships without having passed all the necessary tests. In those cases, there were also accusations that the service heavily scripted the events to avoid damaging the vessels.

But it appears that the Navy is rightfully worried that Ford, which it finally took delivery of in May 2017 after repeated delays, might not be able to pass those tests in any form in the near future. Serious questions remain about when engineers will be able to assure systems essential for the ship’s flight operations work as intended at all, let alone after being rocked by a massive explosion in a high-threat combat situation.

Most notably, its Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS), Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG), Advanced Weapon Elevators (AWE), and Dual Band Radar (DBR) have already shown themselves to be finicky and unreliable just during relatively low impact testing. In its latest regular review of U.S. military-wide testing activities, which it published in January 2018, the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operation Test and Evaluation said its overall assessment of the Ford-class “remains consistent with previous assessments,” which have generally been poor.

“Poor or unknown reliability of the newly designed catapults, arresting gear, weapons elevators, and radar, which are all critical for flight operations, could affect the ability of CVN 78 [USS Gerald R. Ford] to generate sorties, make the ship more vulnerable to attack, or create limitations during routine operations,” the report says in the initial summary of its section on the carrier. “The poor or unknown reliability of these critical subsystems is the most significant risk to CVN 78. Based on current reliability estimates, CVN 78 is unlikely to be able to conduct the type of high-intensity flight operations expected during wartime.”

In theory, the Ford’s EMALS and AAG are supposed to allow the ship’s crew to better fine tune how they launch and recover aircraft compared to the existing steam-powered catapults and arresting systems on the Nimitz-class. This in turn would speed up both processes, improving the ship’s ability to get aircraft into the air and get them back on board during high-intensity operations, all while reducing wear and tear on the ship and the planes. This in turn reduces the maintenance workload for personnel on board and could allow for the carriers to operate with smaller crews, saving the service on various costs and easing strains on already limited manpower.

Testing during the 2017 fiscal year showed that both the EMALS and AAG remain horribly unreliable. As of June 2017, the electromagnetic catapults suffered a critical failure after an average of 455 launches, nine times more often than the Navy’s own threshold requirement.

As such, Ford had an approximately 70 percent chance of completing just one day of sustained operations without a major problem with the system. When a problem did occur, the crew would have to spend 1.5 hours just waiting for the system’s generators and motors to shut down before they could even begin trouble shooting the issue. There is no way to electrically isolate specific components individually so maintenance teams can safely inspect them.

The AAG’s reliability was even worse, with it being able to withstand recovering an average of fewer than 20 aircraft before experiencing a major issue. The Navy’s target is for the arresting system to be able to handle approximately 16,500 landings before experiencing a failure. As it stands now, Ford has around a one percent chance of being able to make it through a normal day of flight operations—recovering roughly 84 aircraft over a 24 hour period—before its arresting gear breaks down.

These statistics are a far cry from how the Navy has described the situation in the past. “When that ship delivers we’ll be ready to land aircraft on AAG,” Vice Admiral Thomas Moore told USNI News in 2016. “I think [CVN] 78 [USS Gerald R. Ford] is doing much better and I think we’ll have a fully functional system.”

The Navy has demonstrated that it could indeed land aircraft on the carrier using the AAG, as well as launch them again with the EMALS, during at-sea tests in 2017. It’s hard to reasonably say either system is “fully functional,” though, or even near to it.

The Director of Operational Test and Evaluation report says the Navy could only provide “engineering reliability estimates” for the Advanced Weapon Elevators (AWE) and Dual Band Radar (DBR). It included no specific details about the elevators, which are essential for getting aircraft on and off the flight deck.

Existing test results for the ship’s multi-function Dual Band Radar, which is supposed to support air traffic control functions and watch for and help target incoming threats, have not been reassuring. According to the review, land-based testing showed the system has problems tracking missiles in flight and cuing its own defenses to engage them, routinely gets confused by “clutter” and displays false information, and otherwise has trouble accurately showing the proper position of actual items of interest.

These could present serious issues for the ship for a multitude of reasons, but especially it needed to defend itself, since it would rely on data from its radars to guide the latest variant of the RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM) to it targets. The ESSM is one of the ship’s primary means of self-defense against aerial threats.

On top of that, during a limited test of the system on Ford, the radar kept unexpectedly shutting down. In addition, no one has yet assessed the reliability of the Volume Search Radar portion of the DBR at all. Maybe the most disappointing part of all this is that future Ford class variants will rely on a different radar system altogether, which points to the Navy’s own disdain for the DBR.

There’s a serious underlying concern about the ship’s main power generation system, as well, which is necessary to keep all of these components running. Before delivering Ford to the Navy, Newport News Shipbuilding reported a failure in a transformer attached to one of the ship’s four main turbine generators.

According to the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation, the Navy, not wanting to delay getting the ship any further, approved the use of an existing transformer design it already used for other applications as a substitute. It conducted no testing to determine if this component would work properly with the rest of the carrier’s electrical systems.

“Voltage regulating system design flaws resulted in damage to a second main turbine generator following a subsequent transformer failure,” the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation’s report says. “This incident delayed the ship’s delivery as well as both live fire and operational testing and currently [as of September 2017] the ship is operating on three of the four main turbine generators as a direct result of the second failure.”

Unfortunately, as the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation’s own review says up front, these issues are hardly new or even necessarily unexpected. When it began the program to develop a new carrier more than a decade ago, the Navy relied heavily on a concept called “concurrency,” whereby it would hire contractors to begin work immediately on production without having a final design fleshed out or its components tested.

As we at The War Zone have noted repeatedly, this entire theory, applied to the Ford-class and other systems, has turned out to be a farce. Both the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and Newport News said the Navy’s belief that it could build Ford for less than $10.5 billion was almost comically optimistic and they turned out to be entirely correct.

Each one of the Ford class carriers now carries a price tag of nearly $13 billion, which was fully in line with earlier estimates from GAO and Newport News. However, the true costs are now likely to be higher as the Navy now has to spend extra time and money making sure the ship’s various systems, many of which engineers have only tested on land to a limited degree due to concurrency, actually work.

All of this has meant that the Navy was already disinclined to conduct the shock testing on Ford and had wanted to focus on getting the ship into at least limited service first. The service had previously advocated for running the trials on the USS John F.

Kennedy and assuming the results would hold for both ships. But by then the Ford would supposedly be operational for years, albeit in an unvetted form.

Former Secretary of that Navy Ray Mabus vetoed that plan in 2015 and announced plans for Ford to go through the shock tests in 2019. Now, it appears that the service wants to return to its initial plan. It expects to commission Kennedy in 2024, or six years from now.

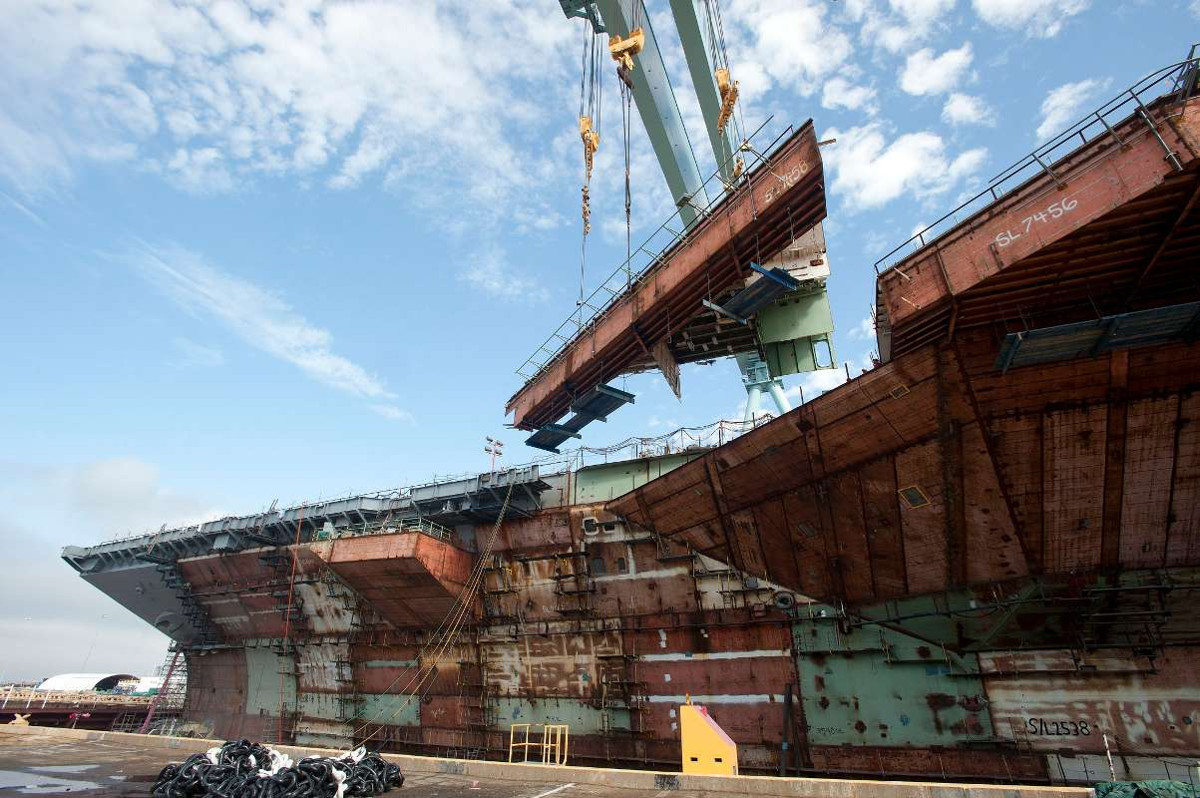

It’s not clear how any of these developments will affect the delivery schedule for the future USS John F. Kennedy, which is already under construction. The Navy has four Ford class carriers in hand, under construction, or on order, in total.

Aircraft carriers take too much time and money to build for the Navy to simply relegate Ford and even possibly Kennedy to non-combat roles – something the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Marine Corps are considering doing with early production F-35 Joint Strike Fighters that they also bought under a concurrency scheme – and hope the situation improves with the future ships in the class. You can read all about this harsh reality here.

The service already has to contend with a “carrier gap,” which makes it difficult to deploy enough flattops to meet demands, let along surge them in a crisis. This became particularly apparent when details emerged about what it took to get three Nimitz-class ships together for a massive show of force in the Pacific in 2017.

The oldest of the Nimitz class ships have been in service since the 1970s and are headed toward the end of their estimated 50-year service life whether the Navy has replacements or not. It’s becoming an increasingly more serious gamble that systems like EMALS and AAG will be ready for real world operations by the time it is absolutely necessary to have the ships they are installed on available for deployments. The Navy could decide to replace one or both of those systems on Kennedy and later ships in the class with existing steam-powered versions, an idea that President Donald Trump blurted out in an interview in May 2017, but retrofitting the design would be hugely time consuming and costly in its own right.

This is all happening as the Navy is struggling to maintain the surface ships and submarines it has amid a dangerous shortage of manpower and flagging morale. It now has to balance the Ford-class debacle against the urgent need to revitalize and expand its own shipyard capacity and improve training and overall readiness, as well as its long-standing desire to acquire more ships in general.

With regards to the shock trials specifically, the Navy now finds itself in a no-win situation almost entirely of its own making. Given the poor reliability of its systems to begin with, Ford is unlikely to pass the shock trials without at least some significant issues, which would be another embarrassing development for the ship. On the other hand, one cannot reasonably see putting the trials off for six years as anything but a tactic admission of this fact.

“I think we have to know if those systems continue to work in a combat environment,” Robert Behler, the Director of the Office of Operation Test and Evaluation, told Bloomberg in an interview. But that decision “is not mine to make” he added.

There’s no guarantee that a shock trial in 2019 would even accurately reflect the ship’s vulnerabilities due to the continued work on its critical systems. It’s also unclear when the ship would actually be ready for service at all.

At this point the possibility that it could be years before Ford is ready to deploy operationally into potential combat environments isn’t unthinkable. This might’ve made the shock trials delay irrelevant, except the Navy is building more of the supercarriers to the exact same design specifications. It could end up that major issues are found structurally with the design even after two of the vessels are totally complete and another nearly finished.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com