Much like its fellow warfare branches, United States Naval Aviation, or NAVAIR, has been built upon a foundation of rules, procedures, and traditions. Its aviators, however, have an uncanny personality not readily found in the other warfare domains: from their helmet-adorned crown, down across their patch-laden leather flight jackets, to the soles of their brown-shoed feet. That cocky, self-assured personality contains a rebellious there I was creativity willing to defy, within reason, the accepted norms of a Navy that needs to keep them reined in. One can find this character displayed in the stories of the art that defines their squadron patches.

My S-3 Viking unit, Air Anti-Submarine Squadron Twenty-Four (VS-24) was officially known as the “Scouts.” However, we also had another, unofficial — but officially accepted — squadron name, patch, and story known as the Duty Cat.

Called to the ready room

One late afternoon in January 1987, just after we passed into the Mediterranean Sea aboard the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN-68), AW2 Gil Gregg entered the VS-24 aircrew berthing informing me and AWAN Jones (callsign “War Baby”) that our presence was required in Ready Room 4. Gil, the prankster, added: “NOW! And you two are in a world of shit!”

In our fear and trembling, neither of us noticed that the other AWs (Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operators) were standing there with shit-eating grins etched across their faces.

Young Jones and I made our way, with a quickened nervousness, down the starboard 0-3 passageway and entered our ready room only to find the entire cadre of VS-24 officers there already. For the first time, I noticed the entourage of AWs from the berthing had piled in behind us… what had we done!?

“Nooner and War Baby! Up front!” our executive officer (XO) bellowed.

The joke, of course, was on us. We weaved our way among several pilots and Naval Flight Officers (NFOs) at the front of the ready room, careful not to trample on the deck tiles depicting the squadron’s iconic mascot. Our commanding officer (CO), Rocco Tominelli, who long ago flew the venerable S-2 Tracker, stood, and ordered the ceremony of the Awarding of the Duty Cat to commence.

A dark and stormy night (no, really… it was)

As the most junior officer (JO) among the awardees nervously stepped to the briefing podium, fumbling with his left breast pocket, an officer standing next to him unfurled a bright red flag. Centered on the flag was a very odd-looking black cat, its eyes crossed out and a lightning bolt striking its hind quarters. It was difficult to determine if the cat was dead or alive. From his pocket, the NFO pulled and unfolded a piece of paper and began to tell the tale of the Duty Cat:

“In 1948, VS-24, composed of 18 torpedo bombers, was ordered to the USS Wright (CVL-49) for a shakedown training cruise. One night during rough seas and stormy weather, flight operations were commenced, and a young squadron pilot drew a lightning-struck feline on the ready room briefing board. Throughout the night, the squadron flew sortie after sortie, braving the inclement weather and enduring the long hours of flight operations. The night’s missions completed safely, the flight crews returned to find their feline friend firmly affixed in chalk maintaining a vigil. Defiant, dauntless, pernicious yet serene, the image instilled vitality among the flight crews. From that time on, it was decreed that flight operations would not commence until the Duty Cat was placed on watch.”

A brief but complicated history of VS-24

It’s a great story if that is what happened in 1948, onboard Wright, in a squadron with 18 torpedo bombers. Harnessing the ‘actuals’ and ‘facts’ of naval history is, in a word, difficult. Herding cats is a far easier task than finding a consensus on what actually occurred. No one has written a single, well-researched book on the life of VS-24 that spanned over 66 years.

Sadly, even the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) website offers just two volumes of the Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons covering attack and patrol units. Hopefully, at some point, additional chapters will cover fixed-wing anti-submarine (VS), helicopter (HS), and fighter squadron (VF) histories and lineages. The only documented account of the Duty Cat’s story I could find is in the November 1960 issue of Naval Aviation News.

While most NAVAIR units assigned someone to maintain the squadron’s official history, that task normally fell into the overly eager arms of a newly arrived JO or the squadron’s intelligence officer. It wouldn’t take long for the weighty list of additional collateral duties, also piling up in his arms, to crush any sense of creative initiative and ambition. As I recall, the total effort to keep the historical record during my time at VS-24 consisted of a threatening XO loudly demanding: “You better damn-well make sure you’ve submitted something on what we’ve been doing out here in the Med for the next issue of Tailhook Magazine or the Skipper will have you buffing floors with the AWs for the rest of this and the next cruise.”

So, free of threats and collateral duties (but fearful of not getting it right), come along with me on a journey through the years as I attempt to herd a variety of publications and online sources together and explain how my squadron arrived at that day when I was awarded my Duty Cat.

VB-17

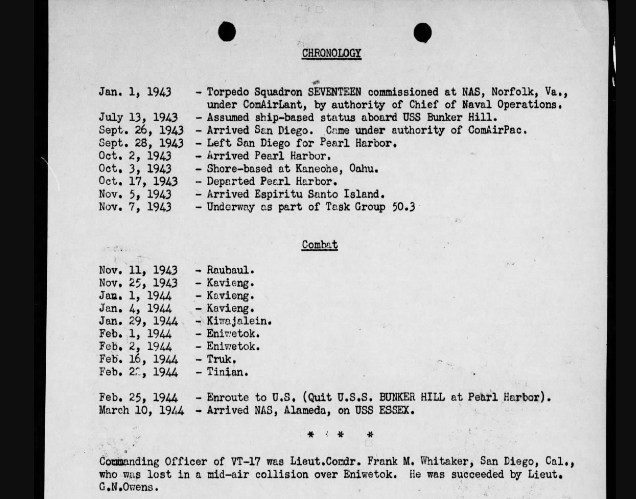

VB-17 was born “In Hangar LP-4 at Norfolk, Virginia, Naval Air Station (NAS) on New Year’s Day, 1943,” writes Robert Olds in his book Helldiver Squadron: The Story of Carrier Bombing Squadron 17 with Task Force 58, published in 1944. “Four new squadrons were formally commissioned — Torpedo 17, Fighting 17, Scouting 17, and Bombing 17.”

The author was invited by the War Department to document the first SB2C Helldiver squadron’s aggressive immersion into the Pacific War from September 1943 to February of the following year. Carried into the hornet’s nest aboard the USS Bunker Hill (CV-17), the squadron attacked Rabaul, Kavieng, Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Truk, and Tinian over a four-month period.

Throughout the story, Olds’ documents how the “Helldivers were sent out daily on anti-submarine patrols…” However, he doesn’t describe any combat action with these undersea warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Despite this, the original anti-submarine warfare (ASW) DNA was identified and would be replicated along the ancestral lineage that led to VS-24.

Olds’ book ends as the squadron returns to Pearl Harbor at the end of its first combat deployment. Apparently, VB-17 would continue to fight in the Southwest and West Pacific for the remainder of the war flying from USS Bunker Hill and USS Hornet. In the post-war turmoil, however, the squadron gets lost until Bombing 17 is redesignated VA-5B on November 15, 1946.

VA-5B “Black Lancers”

Rapidly evolving but still young, NAVAIR experienced squadron-level chaos that the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) attempted to define and control. Squadron designations, aircraft types, home bases, and deployments on specific aircraft carriers shifted — sometimes wildly — amid a world without war, a country with too many warfighting assets, and a rising Soviet threat everyone just wanted to ignore.

“The squadron received its first AD-1 Skyraider in October 1947,” writes Steve Ginter in his highly detailed two-volume work on the AD Skyraider, affectionately known as the ‘Spad’ and ‘Able Dog.’ “By 15 December 1947, VA-5B had its full complement of twenty-four AD-1s while still operating eight SB2C-5s and one SNJ.” I had no idea that my squadron flew the most remarkable combat aircraft, in a line of legendary airplanes, designed by Ed Heinemann!

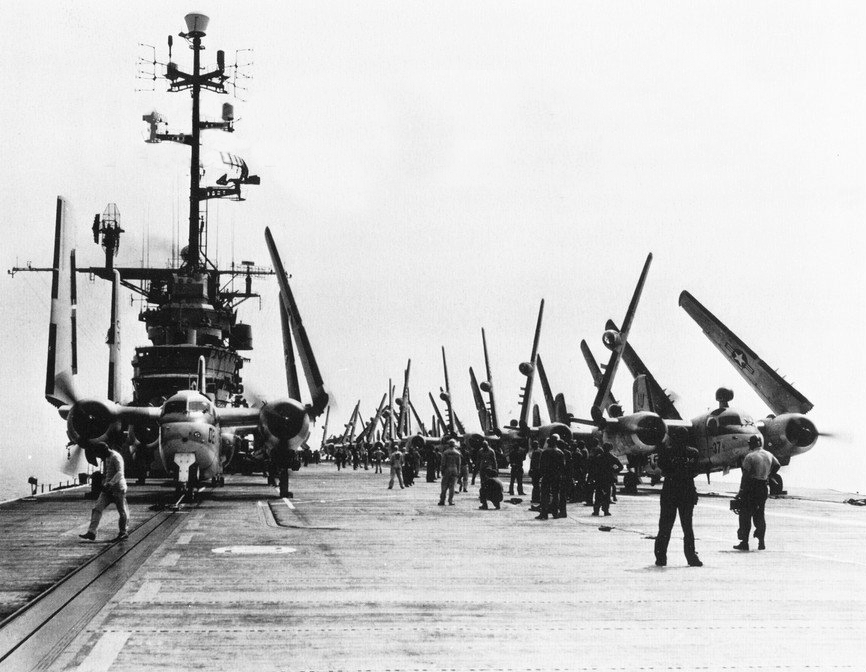

On December 10, 1947, CDR Paul Buie, the CO of VA-5B, is shown in a series of photographs making the first arrested landing and first deck-run takeoff from the newly commissioned USS Coral Sea (CVB-43) in a Spad. The squadron would embark upon the Coral Sea for her shakedown cruise from January 19, 1948, until April 5, with the rest of the carrier air group (CVBG-17) consisting of VF-5B/VF-6B, both flying F8F Bearcats and VA-6B, also flying the AD-1. No sources identify the presence of Helldivers aboard the aircraft carrier or with the “Black Lancers” during this deployment.

VA-5B would again embark on the Coral Sea for pilot carrier qualifications (CQ) in May and June 1948 before the third Midway class carrier set off on its first, very short Midshipman/Mediterranean cruise with an entirely different air wing on June 6. Meanwhile, the Navy stepped in on July 27 and changed the designation of the “Black Lancers” from VA-5B to VA-64 in what appears to be an attempt to simplify the numbering of its aviation squadrons.

VA-64 “Black Lancers”

The Coral Sea returned to the United States on August 6 and the newly designated squadron joined the carrier for a post-overhaul cruise to the Caribbean in September. Then in November, VA-64 embarked on the USS Midway (CVB-41) for a six-week work-up in the Caribbean where according to an article in the February 1949 issue of Naval Aviation News “the squadron turned in some credible shooting… both with Tiny Tim rockets and torpedoes. Using these two weapons for the first time, its pilots made four hits out of six with the torpedoes and 80 percent with the rockets.” The article continues describing the numbers of hours and carrier landings the pilots made “in the AD-1.”

But what about the USS Wright? Over most of 1948, the “Black Lancers” flew from the big-deck Midway class aircraft carrier decks. Then, at the end of 1947, the Wright:

“…underwent post-shakedown repairs and alterations before she returned to Pensacola two days before Christmas where she resumed her regular schedule of pilot qualification training under the operational control of the Chief of Naval Air Training, Commander Air Atlantic. Wright spent the year 1948 engaged in those pilot carrier qualification operations, before she put into the Norfolk Naval Shipyard on January 26, 1949, to commence a four-month overhaul.”

I’ll concede to the very real possibility that VA-5B/VA-64 performed CQ on a dark and stormy night aboard the light carrier at some point in 1948 between deployments aboard Coral Sea and Midway. Nevertheless, I’ve found nothing to support that.

As to the issue of the “18 torpedo bombers” recited in both the 1960 Naval Aviation News article and the 1987 version of the story, a third source also uses the number 18 to describe how many aircraft the next squadron in the lineage would have. Now, let me add another layer to further muddy the already confusing waters. Not only are there 18 aircraft in this subsequent squadron, but they also just happen to be post-war variants of the TBF/TBM Avenger. Even so, let me emphasize a very important point: the timeframe associated with this squadron is from 1949 to 1950, not 1948.

Could the lightning-struck feline have been drawn on a ready room chalkboard in 1949? That third source, a book about the S2F Tracker written by Doug Siegfried, a Tracker pilot, and Steve Ginter offers yet another layer: “The squadron took on the nickname ‘Duty Cats’ in 1948, based on a cartoon of the lightning-struck cat that symbolized night-carrier qualification” (italics mine).

It’s bewildering, isn’t it? But it seems to be less and less likely that the original story of the Duty Cat was inspired while the squadron was flying torpedo bombers. It is a fact that the Helldiver could carry torpedoes, but I could only find two VT (torpedo) squadrons listed that flew the SB2C. Additionally, I think the use of the phrase “torpedo bomber” just didn’t make sense for three reasons. Firstly, torpedo bombers had quickly become obsolete at the end of World War II due to the technological advancements in shipboard air defenses. Secondly, the ‘T’ in the VT designation would change on November 15, 1946, from ‘torpedo’ to ‘training’ squadron. Finally, the 18 Avengers I mentioned above were TBM-3E and -3S anti-submarine variants, not torpedo bombers.

A deeper dive into the Naval Archives or the historical records held at the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola might clear all of this up. Until that clarification can be found, I’m going to assume that in 1948 the newborn Duty Cat was drawn on a chalkboard to protect a bunch of pilots performing carrier qualifications aboard the USS Coral Sea while flying the AD-1 Skyraider. I love the Spad!

#FightMe

Why a (Black) Cat?

For an animal whose behavior can be so wonderfully or infuriatingly similar to their human ‘owners,’ it might make complete sense (or none at all) that the use of a cat in NAVAIR symbology was both common and popular.

I’m quite surprised, however, that the black cat was so readily used considering its reputation in the European and American past. Normally associated with satan, witches. and various emanations of the occult, its widespread 20th-century military use indicates a successful evolution into an animal signaling a sense of defiance against a variety of enemies. Many examples abound, but two immediately come to mind:

Felix the Cat has had a long, storied history and the public was already charmed by his antics on theater screens prior to World War II. But when they saw his bomb-carrying image in newsreels and newspapers as a squadron symbol associated with the Battle of Midway and the exploits of fighter pilots like “Butch” O’Hare and John S. Thach, the clever cat would achieve magical status. One of my favorite cartoons growing up in the 1970s, I had no idea Felix was riding the fuselages and tails of the Phantom IIs and Tomcats of VF-31.

The “Black Cat Raiders” of World War II fame finds another legendary use of the black cat image. Their nocturnal PBY Catalinas accomplished remarkable things under the cover of darkness, sabotaging the Imperial Japanese Navy’s attempts to hide and complete their own operations.

And, next to the Duty Cat, my favorite squadron emblem belonged to the U-boat hunters of VC-13. I just can’t get over their image of a cocky black cat boldly flying a double shot of the middle finger.

Now, let’s continue on the trail that leads to my squadron.

VC-24

“On April 8, 1949, VA-64 was redesignated Composite Squadron Twenty-Four (VC-24) and had two AD-1s on hand on April 31,” Ginter writes. “Only TBM-3Es were on hand in June 1949.” The squadron would end up flying with a normal complement of 18 TBM-3s. These comprised the E-model with wing leading-edge radar, wing hardpoints, deleted gun turret, and the S-model (ASW strike) variants. During its short life, VC-24 would give up the big-deck carrier life for the 557-foot escort carrier USS Palau (CVE-122).

According to NAVAIR, composite squadrons were designed “to identify a group of squadrons with several different missions…includ[ing]…anti-submarine warfare…” The squadron numbers were significant. A single digit indicated night or attack units. Numbers in the teens were given to airborne early warning (AEW) and ASW squadrons had numbers in the twenties and thirties. Thus, with the numerical designation of 24, the Navy decided to focus the mission of a former attack squadron on ASW.

It was a prescient move. In the next five to 14 months many events were about to take place:

Several sources, including Jane’s Fighting Ships, would sound the alarm that the Soviet Union could have up to 1,000 submarines by the end of 1950, or 1951.

Grumman would deliver a brand new, inadequate team of ASW hunter-killer aircraft to replace their obsolete Avengers.

North Korea would invade the South, igniting concerns that the Navy would be fighting an anti-submarine war it was unprepared for.

VC-24 would no longer exist.

VS-24 (the first go-round)

On April 20, 1950, just 12 days after its first anniversary, Composite Squadron Twenty-Four was redesignated VS-24. In the past, VS was used to identify a ‘scouting’ squadron. From 1950 until the mid-1980s, the designation would stand for Air Anti-Submarine Squadron, reflecting the growing emphasis on ASW. VS-24 held on to its Avengers until September.

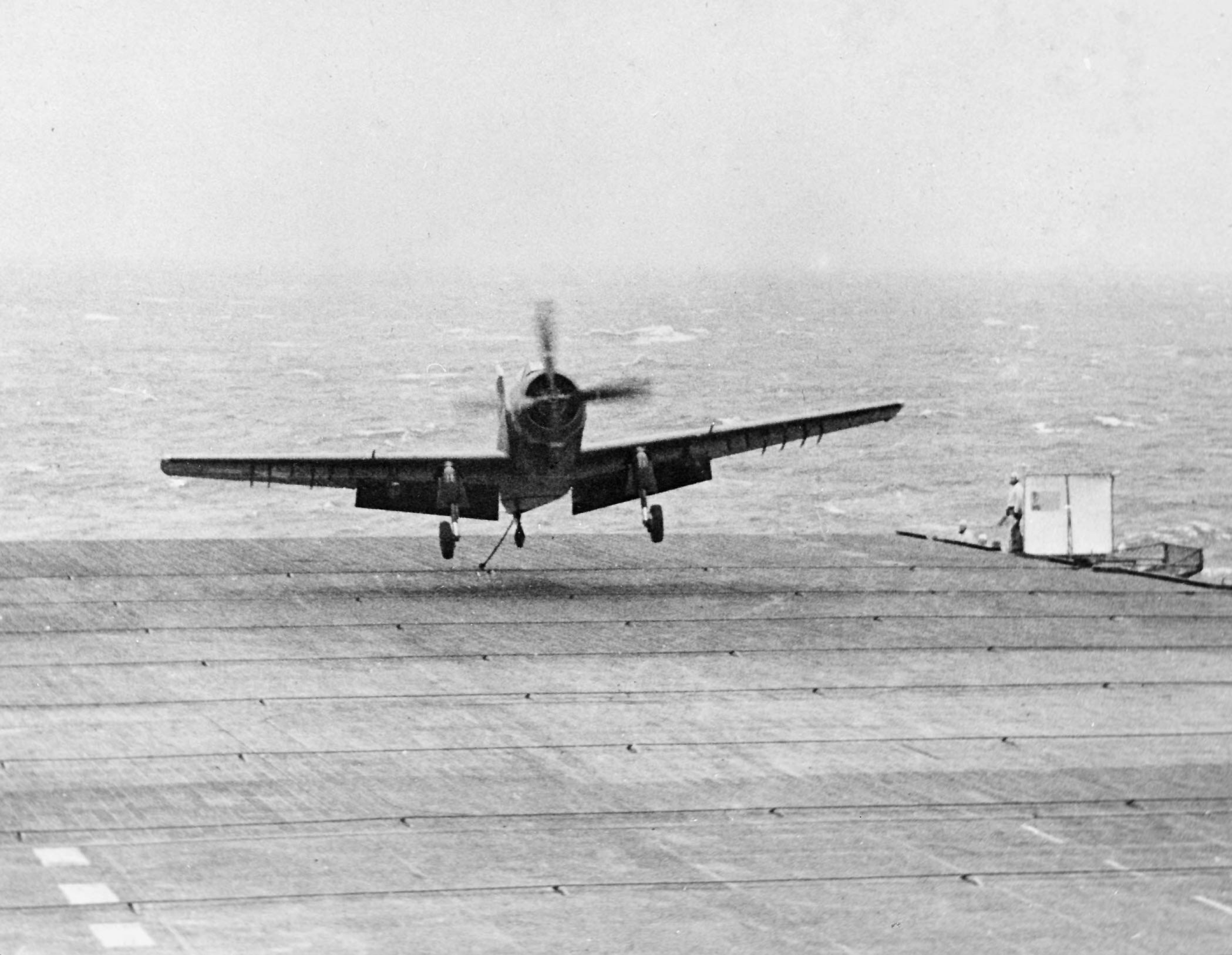

The squadron had been picked by NAVAIR to be the first to receive the Grumman AF Guardian. A total of 18 aircraft would be delivered forming a hunter-killer team: nine of the AF-2W version, known as the ‘Guppy’ because of the large bulbous AN/APS-20 radome protruding from the belly, and nine of the AF-2S attack version of the aircraft.

As the first squadron to receive the new aircraft, VS-24 was charged with the responsibility to evaluate the Guardian team for the fleet. First up were carrier suitability tests that would bring them back aboard the USS Palau in December and then again in January of 1951. Developing aircraft flight and handling procedures as well as ASW tactics suitable for the performance of their new aircraft would occupy the months that followed.

Pilots and aircrews from all the VS squadrons would soon become painfully aware of the airplane’s shortcomings and faults, some of them dangerous and many which could not be solved over the Guardian’s short life. In a letter to the Naval Aviation Museum’s magazine Foundation, written almost six decades after his last flight in the aircraft, John Morse expressed his feelings about the AF: “After training in Corpus Christi and receiving my Wings of Gold in the great ‘Able Dawg,’ I met the ugliest, most underpowered, poorly instrumented (for its mission of all-weather flight) dog of an aircraft that Grumman (and maybe anyone else) had ever manufactured.” Being underpowered contributed to many of the aircraft’s numerous mishaps.

The issues described by Morse were only exacerbated by a NAVAIR decision to fly the Guardian, almost exclusively, from the very small decks of escort and light aircraft carriers. Even squadron and flight deck crews had great difficulty with the ungainly aircraft. At one point, the CO of VS-24 required his pilots to man the airplanes every time an aircraft was moved on the flight deck or in the hangar bay due to the extremely high rate of towing collisions and consequent damage. Sitting in the cockpit to ‘ride the brakes’ was normally done by a very junior enlisted plane captain. Without affection, the Guardian soon acquired the name ‘Able Fud.’

It should come as no surprise, then, that the Duty Cat found itself being drawn on another ready room chalkboard. This time, we can be certain of both the aircraft carrier and the type of aircraft that inspired this feline resurrection. The USS Gilbert Islands (CVE-107) was conducting CQ off the Atlantic coast for VS-24 in January 1953.

Oscar Schaer, CDR, USN (Ret.) writes the following in Grumman AF Guardian:

“We had 10 planes up for night quals and the pilots were getting a lot of wave-offs. Someone said [to] draw the Duty Cat on the board. We did and all of the sudden, the pilots started coming aboard. From that time on, the Duty Cat was drawn on the ready room board whenever we were embarked.”

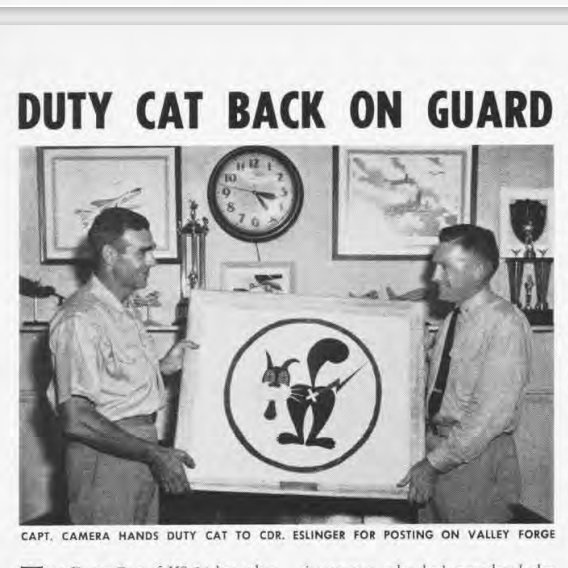

VS-24’s evolution as an itinerant squadron would continue until 1960 when a sense of platform, air wing, aircraft carrier, and land basing permanence would finally begin to set in. The squadron mascot would also trade the impermanence of the chalkboard for a framed plaque that could easily be perched at the front of the ready room during flight ops and stored away when the flight deck was quiet.

In the meantime, the summer of 1951 would find the squadron transferring from its home base at NAS Norfolk to NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island. In late 1954, their Guardians were exchanged for the latest Grumman ASW aircraft, the S2F-1. And then, in the summer of 1956, VS-24 was decommissioned.

VS-24 (the second go-round)

“On April 1, 1958, Antisubmarine Defense Group Alfa was established by the Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet… it consisted of an augmented Hunter-Killer Group and had a primary mission of advancing anti-submarine defense in the Atlantic Fleet. Forces assigned were to operate with the Group on a semi-permanent basis. Under the original directive, the group was set up for an 18-month period, although present indications are that it will be continued for an indefinite period. This probability is reinforced by the establishment of Task Groups Bravo [focused on hunter-killer tactics] and Charlie [focused on escort of convoys]… In addition to the forces normally comprising a Hunter-Killer Group (a carrier, destroyers, carrier fixed-wing aircraft, and helicopters), Task Group Alfa was augmented by two anti-submarine submarines and a patrol plane element.”

— “Antisubmarine Defense Group Alfa” by CAPT Thomas McGrath in USNI Proceedings, August 1959

The U.S. Navy was very worried. The USS Nautilus (SSN-571), the world’s first nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN), had the surface escorts, aircraft carriers, and ASW aircraft running helter-skelter trying to keep the fast and maneuverable submarine localized and tracked as it assaulted their screens. And now, the Soviets had three operational Project 627A November class SSNs operating with their Northern Fleet.

Admiral Arleigh Burke, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), assigned the genius tactician and fighter pilot, CAPT John Thach, with the task of weaving together a plan for ASW forces to defeat the submarine threat. The Navy had begun converting most of its Essex class aircraft carriers to ASW carriers back in 1953. Now, Admiral Burke authorized anti-submarine carrier groups (CVSGs) like those described above.

On May 25, 1960, the second VS-24, officially named the “Scouts” was born again. According to Siegfried and Ginter, “…CVSG-56 was formed at NAS Norfolk causing VS-27, a large 20-24 [aircraft] S2F-1 squadron to be split in two to form VS-24.” Until 1973, the “Scouts” would remain with this anti-submarine group.

Over the years, the squadron would still deploy on various ASW carriers based on availability. For the most part, however, they would call the USS Intrepid (CVS-11) home. Stationed at NAS Quonset Point, which was also a deep-water port, they had the advantage of having most of their carriers home-ported right there with them.

Because of this relative stability, the squadron decided to make the Duty Cat’s presence in their ready room aboard Intrepid far more permanent. For the first time, they created floor tiles with the cat’s image on them and placed them on the deck at the front of the squadron’s gathering place.

In the early 1970s, with the end of the very expensive Vietnam War, the Navy was hard-pressed to obtain a good share of the dwindling defense budget. As a result, all ASW carriers were decommissioned. The CVSGs were broken up and their squadrons were dispersed among the supercarrier air wings as the Navy moved from the attack carrier (CVA) to the multi-mission carrier (CV). Also, as part of a money-saving effort, NAS Quonset Point was closed in June of 1974 and all the VS squadrons moved to NAS Cecil Field, Florida.

On September 27, 1974, with very little time to settle into their new Florida home base, the “Scouts” would join CAG-3 aboard the USS Saratoga (CV-60), which was homeported about 40 miles to the east at Mayport Naval Station. This would be the squadron’s final S-2 Tracker deployment. Two years before, the ‘Sara’ had evaluated whether equipping attack aircraft with sonobuoy pods would help make the ASW team protect the carrier battle group from the much-advanced threat of nuclear submarines that were now carrying anti-ship cruise missiles, along with keel-breaking torpedoes. You can read more about that little-known experiment here.

Despite flying the most advanced (and final) version of the S-2, the G-model, VS-24 and the Navy knew the Grumman aircraft couldn’t fly fast enough to cover the mid-outer ASW zone that surrounded the aircraft carrier battle groups (CVBGs). More importantly, the Tracker simply had nowhere else to grow in a world of rapidly advancing submarine and ASW technology.

After the Scouts returned from their Mediterranean deployment aboard the Saratoga, they spent the next two years transitioning to the S-3A Viking which had just joined the fleet. Then, on December 1, 1977, the squadron would begin a 10-year relationship with CAG-8 and the USS Nimitz, embarking on their first deployment with their new aircraft aboard the lead ship of the Navy’s newest class of nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.

Once again, the “Scouts” had found a long-term home and the Duty Cat would take its place of permanence in deck tiles at the front of Ready Room 4.

The rest of my story

Aboard Nimitz in 1987, that JO who was telling the tale of the Duty Cat completed the story and then fumbled in his pocket again for another piece of paper. This time, he began reading the poem he and the other newly qualified officers were obliged to write. The poem’s purpose was to creatively mock the CO, the XO, and all the squadron department heads. If his literary efforts were considered appropriately demeaning by the ‘offended’ senior officers, the ceremony would continue.

The gathered aircrew were then reminded of the requirements that must be completed before obtaining the right to wear the coveted Duty Cat patch on their flight jackets: each of the awardees must have accumulated 10 arrested landings during the day and six at night. Most of the pilots and NFOs were able to quickly achieve these numbers during carrier qualification flights which had occurred before the Nimitz crossed the Atlantic Ocean. The AWs, on the other hand, might not arrive at those required 16 traps so easily. SENSOs were not required to fly in the aircraft during CQ and some squadrons preferred to leave the back seats empty for what could be a dangerous evolution. While I served with VS-24 it was not an issue and most of us jumped at any opportunity to get flight time and rack up the traps.

As the ceremony closed, each of us received a large patch depicting the Duty Cat. In addition to the patch, the most junior SENSO would be tasked with the stewardship of a large, dirty, smelly old stuffed black cat that didn’t resemble the Duty Cat at all. I was an AW3 (E-4). Jones? He was an AWAN (E-3).

War Baby was pissed.

Endings

At the end of our Med cruise, we brought the USS Nimitz around Cape Horn for its transfer to the Pacific Fleet. VS-24 and CAG-8 would acquire the newly commissioned carrier, USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71). We would take the ‘TR’ on its first Med cruise in 1989. When we returned to NAS Cecil Field that summer, we would transition to the most advanced and final version of the Viking, the B-model. Now armed with the Harpoon anti-ship missile, the AN/APS-137 inverse synthetic-aperture radar (ISAR), and an incredible acoustic processing system, the Viking had finally evolved into a genuine threat against any subsurface or surface warship in service at the time or on the next-generation drawing boards.

Reluctantly, I would leave the “Scouts” in late 1990 as they were preparing to go to war. After Desert Storm, VS-24 would deploy to the Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Red Seas in 1993 to participate in Operations Deny Flight and Southern Watch. In the same decade, it would become Sea Control Squadron Twenty-Four (VS-24), as part of a fleet-wide name change reflecting new roles and broader responsibilities.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, VS-24 would, once again, become an itinerant squadron. NAS Cecil Field would close in 1997 and the East Coast VS community would move to NAS Jacksonville, just 19 miles to the east. The squadron and CAG-8 would find themselves flying from the decks of the USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) and USS Enterprise (CVN-65) for various deployments before returning to the Roosevelt.

In March of 2007, as VS-24 was disestablished, the Duty Cat drew its final breath.

Author’s note

I want to dedicate this story to Gil Gregg. A magnificent soul who left us well before his time.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com