In a recently posted new video, a former F-14 Tomcat Radar Intercept Officer, or RIO, describes exactly what happened when he was chosen to take part in the ultra-secretive Constant Peg program and given the unique chance to fly against actual enemy aircraft not far from a desolate airbase near Tonopah, Nevada.

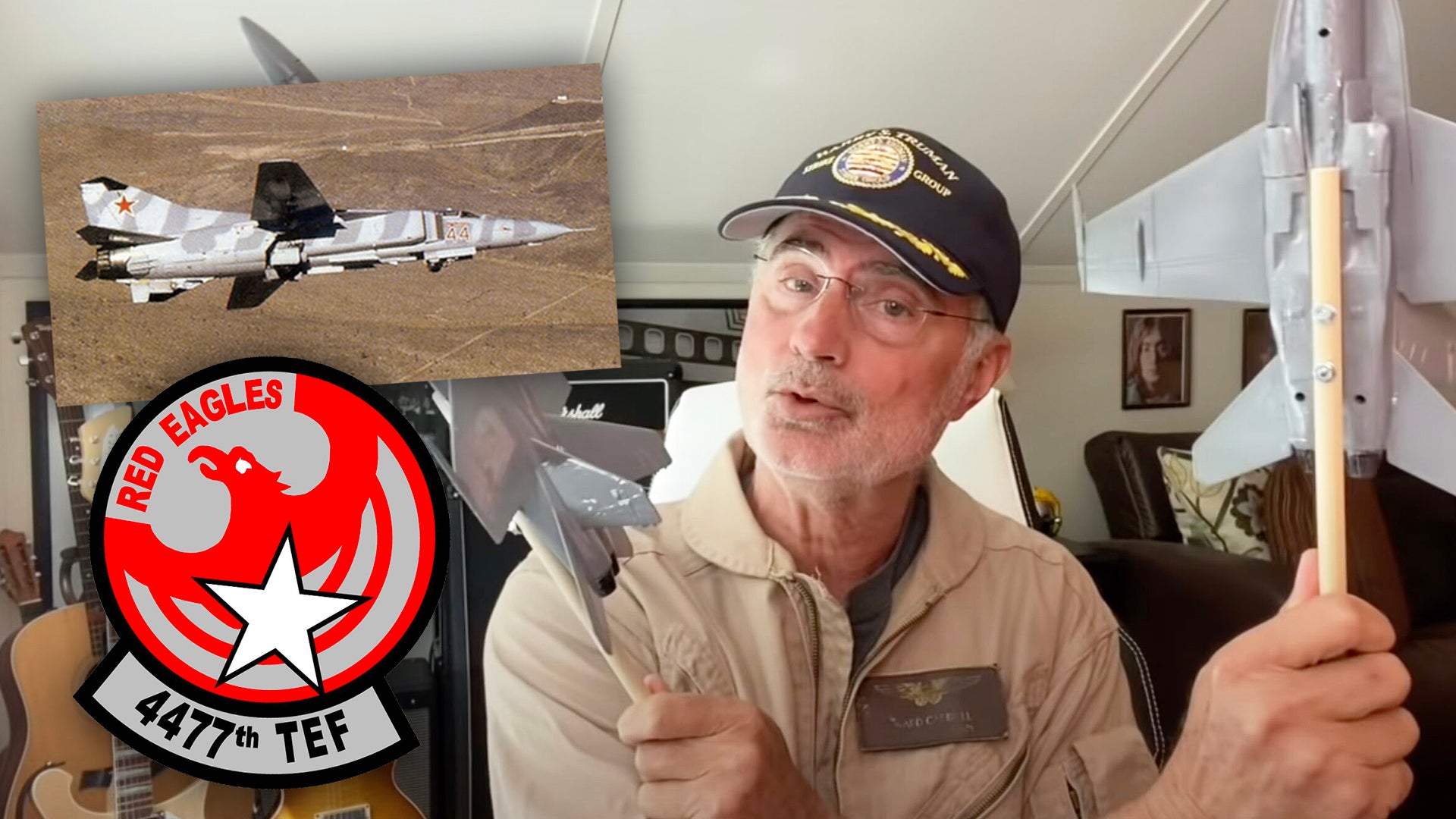

The video, on Ward Carroll’s YouTube channel, is well worth a look, since it deals not only with the mighty F-14 fleet air defender, but also Constant Peg, which yielded the 4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron, or “Red Eagles,” America’s Cold War MiG aggressor squadron. Since the existence of that program was formally declassified in 2006, more and more details, as well as photos and video, have gradually come to light. There are plenty more tales to tell.

In the fall of 1985, Ward was assigned to Fighter Squadron 32 (VF-32), the “Swordsmen,” and, after coming off his first deployment aboard the Forrestal class aircraft carrier USS Independence, was now engaged in workups for his second deployment, a process that took him to Fallon, Nevada — a hotbed of naval fighter activity, then, and now.

“One day we were informed that we were going to participate in an exercise called Constant Peg, something I had never heard of before we got to Fallon,” he recalls.

Constant Peg, of course, was the brainchild of Air Force Colonel Gaillard R. Peck, who had the idea of revamping dogfight training using actual Soviet-made fighter jets. The elite training unit would be made available to Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps pilots. You can see Peck’s awesome brief on the Constant Peg program in this past article of ours.

Ward explains how the instructors serving with the 4477th were the cream of the crop, their posting requiring around 3,000 flight hours in tactical jets as well as graduation from the Air Force Fighter Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, or from the Navy’s Topgun program. In order to preserve the secrecy of the unit, these instructors were technically based at Nellis, a deception that extended to their family members living nearby. For their day job, however, they would be shuttled by C-12 transport plane 150 miles north to Tonopah — “Wild West kind of operations,” in Ward’s considered opinion.

At the time Ward had the chance to go up against the 4477th, the unit was flying the Soviet-made MiG-21 Fishbed and the derivative Chinese-made F-7, as well as both air-to-air and air-to-ground versions of the swing-wing MiG-23 Flogger.

The maintenance effort was another aspect of the “Red Eagles” that really caught Ward’s eye. Mirroring the pilots who flew the jets, the technicians who looked after them — both Air Force personnel and civilian contractors — were the very best in the business. Not only did they sometimes have to fix broken jets using spare parts harvested from crashed aircraft and secreted out of foreign countries by CIA agents, but they kept up an aggressive schedule of flight operations. As of 1985, this called for eight MiG-21 and three MiG-23 sorties each morning, and the same pattern in the afternoon — meaning 11 jets had to be ready to go at any time of the day, without any kind of established spares source.

After a briefing from 4477th crews at Fallon, and another telephone call with the pilots who they’d be flying against, it was time for the sortie itself. This pitted Ward and his pilot, callsign “Truck,” against both an F-7 and a MiG-21 in the space of around 45 minutes.

Using a common radio frequency, the pilots were expressly prohibited from using the real names of the threat aircraft. The Air Force had given the Flogger the cover designation YF-113, while the Fishbeds and F-7s were collectively referred to as YF-110s.

First up was the Flogger and Ward’s initial impression was that the jet was much smaller than he’d anticipated. Until now, the most he’d seen of a MiG-23 was in grainy intelligence photos.

After joining up with the air-to-air variant of the MiG-23, the first point on the flight plan was a speed demo. With Tomcat and MiG-23 side-by-side, the command came over the radio: “On my mark, go to full afterburner.” In the F-14A, the TF30 engines had to be carefully advanced through the stages up to full military power. Not so in the MiG. “Bottom line is, the MiG-23 just walked away from us … First lesson learnt, don’t try to outrun a MiG-23,” Ward says.

Next up were maneuvers with the Tomcat alternating between defensive and offensive starting positions. With the MiG-23 on the offensive, a max-g turn by the F-14 was enough to force the MiG to overshoot immediately. Subsequently, with the F-14 on the offensive, the Navy jet was able to keep pace with the turning MiG, maintain the advantage, and get in close enough for a potential gun kill.

The third Flogger event was a neutral setup, starting with the jets three miles apart and at 350 knots. This time, the MiG-23 pilot dived very low and very fast, and the F-14 crew lost sight of it over the desert. The Soviet jet then reappeared on their wing line and took a simulated shot — it was “a real eye-opener” for Ward and his pilot.

The YF-110 — an F-7 in this case — was next and, conversely, this looked bigger than Ward was expecting.

In the speed demo, the F-14 could keep pace with the Chinese Fishbed clone. In the defensive setup, however, the F-7 was able to hang in the turn with the Tomcat, demonstrating a similar turn rate, but a smaller radius over the first 90 degrees of the turn. Beyond that, the F-7 pilot was “spat out,” unable to keep tabs on the Tomcat and overshooting. With the F-14 on the offensive, Ward and “Truck” could stay glued to the Fishbed throughout the turn.

The neutral setup provided another surprise for the VF-32 crew. With the F-7’s limited turning ability in mind, they didn’t expect the bandit to enter a one-circle fight. But then, the F-7 went vertical “in a way that was very surprising.” The adversary pilot deployed flaps in a “magic move” and was suddenly looming behind the F-14 in an offensive position. Another lesson learned.

“That was so awesome to actually see MiGs for real,” Ward reflected as they headed back from their adrenaline-filled trip over the Nevada desert. A big part of the Constant Peg program was elminating ‘buck fever’ pilots may get when actually seeing a long-touted foreign adversary for the first time, causing them to freeze or be distracted from making a kill.

Meeting the “Red Eagles” was enormously useful for Ward and the tactical lessons imparted from this kind of highly realistic training would be put to use by Tomcat crews during clashes with Libyan jets over the Gulf of Sidra and later in Operation Desert Storm over Iraq.

The two VF-32 aviators also left Fallon with the niggling feeling that there was something more at Tonopah, hidden by the already-secret MiGs. They had been told to not divert to Tonopah Test Range Airport unless they experienced a total failure of some kind. Even a single-engine emergency would have required nursing their jet back to Fallon.

“I think there’s something they care about more than the MiGs,” Ward’s pilot, “Truck,” observed at the time.

There was something else there, of course, with the F-117 stealth combat jet program being run out of the same base. This remarkable aircraft wasn’t revealed to the public until 1988, although the Constant Peg pilots knew about it, and how the exotic planes flew out regularly under cover of darkness.

It was, as Ward points out, “A miracle that they were able to develop and operationally test the stealth fighter in absolute secrecy.” It’s appropriate, therefore, that the same base still sometimes plays host to the F-117, as the stealth jet continues its mysterious second life.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com