Between 17 and 24 AD, an African rebel – and former Roman soldier – named Tacfarinas led a campaign of resistance against the Roman Empire in North Africa, significantly destabilizing Imperial interests in the region. Conventional military tactics proved ineffective for multiple Roman commanders against an enemy who waged a campaign of irregular warfare, launching quick attacks and disappearing back into the desert afterwards. The uprising was only suppressed when the Romans adopted some irregular field tactics of their own, beating their opponents at their own game.

Although the Roman army was one of the most powerful military forces of the pre-modern world, like any other, it had its weaknesses. One particular vulnerability it had was to irregular or guerrilla-type warfare, often encountered as the Roman army expanded into areas of northern and eastern Europe and North Africa. The large and heavily-armed infantry soldiers of the Roman legions often struggled to cope with attacks by lightly-armed enemies, especially those who avoided pitched battle in favor of constant low-level harassment. An enemy leader who could master these tactics against Rome could sustain a campaign against them for years, and cause a significant amount of damage to Roman interests in the process.

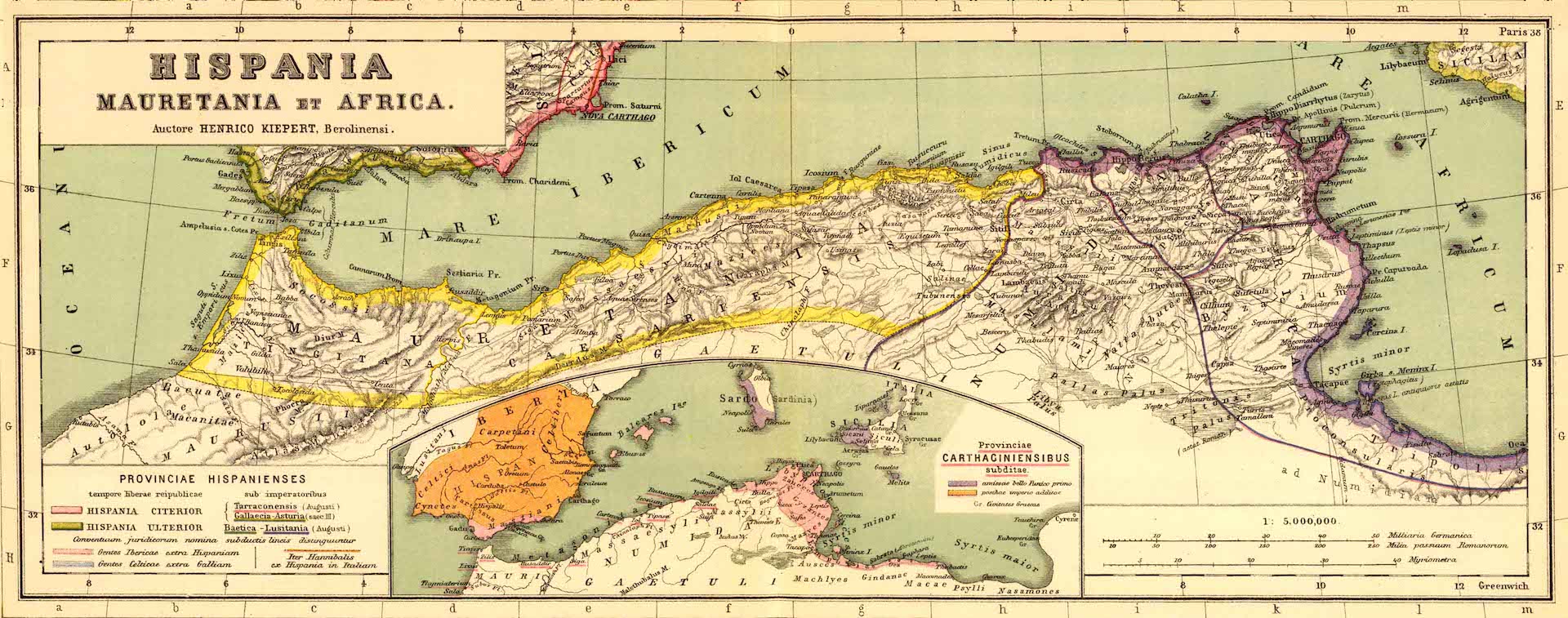

The rebellion led by Tacfarinas was one of the most challenging episodes in the Roman occupation of Africa. Rome’s presence in Africa at this time encompassed a large area, comprised of modern-day Tunisia, northeast Algeria, and western Libya. Not much is known about Tacfarinas himself. He was born in the last decades of the 1st Century BC into the Musulamii tribe, one of the Berber peoples of North Africa based in areas now part of Tunisia and Algeria. At some point during his late teens or early twenties, he enlisted in the Roman army, serving in a non-citizen auxiliary unit raised in Africa. It is not known whether he served as an infantry or cavalry soldier, whether he joined the army willingly, or as part of an enforced levy of men. He remained in the army for an unknown number of years before eventually deserting, turning from a soldier of Rome to a dangerous enemy.

Tacfarinas launched a series of raids against Roman interests in North Africa which rapidly developed into a much more coherent campaign of insurgency. He recruited a large number of wandering lawless individuals, promising them the spoils of raiding, but soon after began to impose on them a discipline that they had previously lacked. Drawing on his experiences in the Roman army, Tacfarinas organized his force into smaller units, imitating the Roman military model. He was soon recognized as a major figure in the region, and appears even to have been recognized as the de facto leader of the Musulamii tribe.

He began to draw in other tribes as allies, including the Moorish Numidian tribes, led by a man named Mazippa. The available troops were divided into two groups. One, under the command of Tacfarinas, was drawn from the best soldiers, who were trained and equipped in Roman-style, as an elite unit; the other, under Mazippa’s command, were lightly armed and less organized, and were sent out to conduct raids and small-scale attacks – to disseminate “fire, slaughter, and terror,” according to the Roman historian Tacitus. They avoided any pitched battle with the Romans, likely knowing that they would almost certainly be defeated if they did, relying instead on hit-and-run guerrilla-esque tactics, which proved highly effective.

The damage inflicted on Roman territories in the region was significantly more serious than the usual raids from the desert, a certain level of which could be tolerated by the Roman authorities – and worse, the heavily-armed forces were unable to mount an effective defense against these swift attacks that came from the desert. Each successful raid added to the economic reserves of the rebels, which could be used to buy more equipment and pay more allies. The situation in North Africa was becoming a real problem for Rome, and the longer it went on, the harder it would be to defeat.

It is not clear what exactly motivated Tacfarinas’ transformation from a Roman soldier to a rebel leader, nor why he entered into a more organized campaign of insurgency in the region – or why the local population embraced the cause so enthusiastically. Some have suggested that the campaign was sparked off by the construction of a Roman road between a military base at Ammaedara and Tacapae (modern Gabés, Tunisia), which cut through the Musulamii territory. This road may have threatened the tribe’s semi-nomadic way of life, particularly as land in the region more widely began to be fenced off and converted from animal pasture to wheat cultivation, and the movement of nomads was becoming increasingly restricted. These Roman policy actions may explain why the indigenous population of the region was ready to support a campaign of insurgency against Rome, but it is still unclear whether there were additional reasons that Tacfarinas chose to lead the resistance as he did. Defending his homeland and traditional way of life may have been motivation enough.

Rome quickly recognized that it needed to respond to the threat in Africa. Tacfarinas’ campaign put security in the region at risk – which provided much of the grain supply for the city of Rome – and with the imposition of discipline on the African rebels, the insurgency would only get harder to suppress the more time that passed.

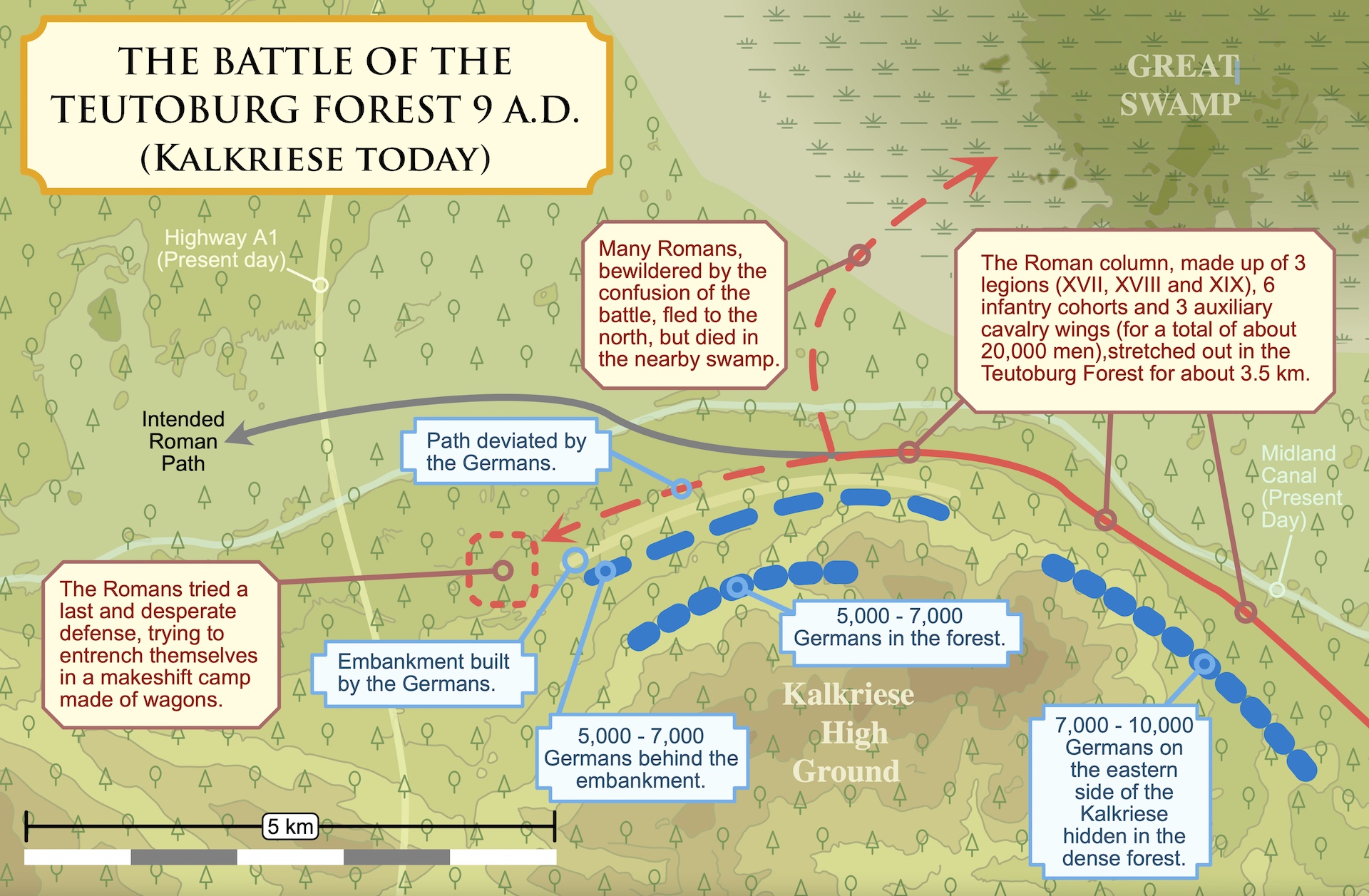

Less than a decade before, in 9 AD, the Romans had suffered a devastating defeat to a German tribal coalition in the Teutoburg Forest in Germany, in which three Roman legions had been ambushed on the march and almost completely wiped out. The Germans had been led by a chieftain named Arminius, who, like Tacfarinas, had served in the Roman auxiliary, and had used his knowledge of the field operation of the Roman army to exploit their weaknesses. Aware that the Roman army had a numerical and technological advantage that would lead to their almost certain victory on a conventional battlefield, the Germans instead attacked them at a time when they were not anticipating any danger, with Arminius having gained the trust of the Roman commander.

The Germans constantly harassed the Romans along the miles-long marching column, launching projectile attacks and then disappearing back into the forest. Although the Roman soldiers resisted annihilation for more than three days, they were ultimately unable to overcome the difficulty of their circumstances, and the majority were killed outright in battle, or captured and either enslaved or executed. The ambush in Germany demonstrated Rome’s weakness to irregular warfare tactics. Roman forces struggled to operate in inhospitable terrain, particularly where they were caught in such areas on the march and where they would be unable to adopt battle formations to defend themselves. The heavy-armed Roman troops could not easily respond to the rapid German attacks, and were unable to move fast enough to extricate themselves from the ambush. After the battle, the Romans struggled to reimpose control in the region, and had only managed to subdue Arminius a short time before the problems in Africa erupted. Even then, it had increasingly become clear that ambitions for Roman territorial control of the German regions east of the Rhine would be abandoned as a result of the defeat – a territorial loss that could not be repeated in Africa.

Accordingly, the Roman proconsul in Africa, Furius Camillus, had no choice but to take action against Tacfarinas. He fell back on the traditional Roman methods of warfare, which favored meeting the enemy in pitched battle, and set out to confront Tacfarinas’ army, leading the only legion stationed in Africa – the Augustan legion – and those auxiliary troops who still remained loyal. Camillus hoped to induce Tacfarinas to meet him on the battlefield, despite his reluctance to do so up until this point. The Romans were severely outnumbered by the African force, which Camillus appears to have counted on to persuade Tacfarinas to fight a pitched engagement, in the hope of winning a decisive victory. Tacfarinas took the bait and led his force into a battle in which they suffered a heavy defeat, losing a significant number of men and resources – although Tacfarinas himself escaped the battlefield.

After this battle, Rome appears to have become complacent, judging that the threat posed by Tacfarinas had been neutralized. The reality was far different. Tacfarinas continued his campaign against Rome in North Africa, having learned to avoid pitched battle no matter how small the Roman army seemed in comparison to his own. Further rapid raids were carried out, too fast for any Roman response to catch or prevent, followed by the destruction of settlements and the capture of ever-increasing amounts of plunder.

The situation worsened when Tacfarinas was able to surround and inflict a heavy defeat on a 480-man Roman cohort. Many of the Roman soldiers caught in the attack were said to have run away through fear of the African rebels, an action which later led to the decimation – the flogging to death of one man in every ten, chosen by lot – of the unit, a military punishment rarely enacted by this point.

Lucius Apronius, the new proconsul of Africa, took the unusual step of ordering this harsh punishment through fear that if he took no action more soldiers would run from future engagements, which would only worsen the situation. His actions evidently worked, as the next time that Tacfarinas and his men attacked a settlement, a small band of around 500 veteran soldiers were able to repel them, each fighting knowing that to run away would invite punishment itself. However, the Romans had still not found an effective way to counter the guerrilla-type tactics used by Tacfarinas and his men, and remained vulnerable to these attacks.

Tacfarinas only encountered difficulties in his campaign when he departed from irregular tactics or allowed his force to become over-encumbered with plunder. On hearing that Tacfarinas was pinned to a certain location due to a large baggage train of looted goods, a Roman force was dispatched to attack the Africans, knowing that they would be unable, or unwilling, to abandon their booty. The Romans sent a deliberately lightly-armed force, made up of the most mobile of their troops. Adopting irregular tactics, Tacfarinas and his men were defeated by the Romans in the ensuing battle, and were driven unwillingly into the desert. This defeat would not subdue the Africans for long, however, and only a short while later they were continuing their campaign against Rome.

The inability to win a conclusive victory against Tacfarinas began to stir debate in Rome. It was felt that more effort needed to be directed toward ending the insurrection in North Africa, particularly as the years of problems were beginning to impact food security in the heart of the Empire. In early 21 AD, Tacfarinas then offered, unexpectedly, a resolution to the conflict. He proposed to end his campaign in exchange for amnesty from the Roman state, and ownership of certain lands in the region, probably those which had once been the traditional grazing grounds of the Musulamii but subsequently fallen into Roman ownership.

His offer was angrily rejected by the Roman emperor Tiberius, seemingly outraged that such a dishonorable enemy – and a deserter from the Roman army, no less – would dare to try and negotiate as if he had political legitimacy.

A third commander, named Quintus Junius Blaesus, became the next man charged with ending the insurrection, by any means necessary. The Romans doubled the manpower dedicated to the campaign by transferring the 9th Hispana legion from the Danube to Africa, in the hope that the extra soldiers could make a decisive difference.

Blaesus approached the problem posed by Tacfarinas in a different way to his predecessors, recognizing that the conventional warfare that the Romans had been attempting to wage thus far was proving largely ineffective against the African force. He, therefore, tried a different approach. Blaesus began by undermining the unity of Tacfarinas’ force, offering them complete amnesty if they surrendered – although these terms were not extended to Tacfarinas himself, who was to be killed or captured. Many of the Africans were won over by these terms, having already prepared to end the campaign when Tacfarinas had sent an offer of peace to the emperor; the war had dragged on, and many were ready to stop fighting and return to normal life. Having reduced the size of the enemy force, he then used the doubled army at his disposal to cover more of the routes used by Tacfarinas to enter Roman territory, garrisoning the eastern, western, and southern borders year-round with small, rapid-response units of as few as 80 men.

Knowing that Tacfarinas would refuse an open battle, Blaesus did not attempt to engage him in one. Instead, he had sub-units trained in desert warfare, allowing them to enter the areas Tacfarinas and his men had previously been safe in, driving them from one camp to another, employing similar techniques to those used by the Africans against Rome. Tacfarinas’ raids into Roman territory were ended by Blaesus’ close control of the frontiers, which had a serious economic impact on his force, many of whom drifted away due to the Roman offer of amnesty and the dwindling opportunities to acquire booty.

By late 22 AD, it was felt that Tacfarinas’ threat had been extinguished, though he himself remained free, and the Romans withdrew from their frontier positions back to normal winter quarters. The 9th legion was returned to the Danube, and Blaesus was acclaimed as the victor who had finally defeated the African rebel. Some warned that victory could not be counted on while Tacfarinas himself remained alive, but these voices were drowned out by the victory celebrations. Unfortunately for Rome, however, Tacfarinas was not quite done yet.

One of the fatal flaws of the Roman strategy against Tacfarinas, and indeed other provincial rebels, was to assume that they would accept defeat when it was upon them, failing to recognize that for the enemy, it was a case of win or die. There could be no acceptance of a return to the status quo before the insurrection had begun, no life of peace to be had until Rome was either driven out, or they had died in the attempt of trying to do so. Even with severely depleted manpower and economic resources, Tacfarinas continued to fight against Rome. The men who had accepted Roman amnesty were replaced by new recruits from the tribes, eager to take their own chances for freedom, glory, and wealth.

Tacfarinas recast himself as a leader of national liberation against Rome, a freedom fighter against oppressive Imperial forces. He claimed that the withdrawal of the 9th legion showed that Rome was weak and could be driven from North Africa with sufficient effort; the defeat in Germany, which had ended Roman occupation east of the Rhine, was no doubt on the minds of leaders and soldiers from both sides. Many were drawn to Tacfarinas’ message, lured in by the desire to end Roman rule in the region, including Mauri warriors from the kingdom of Numidia, alongside a number of ordinary people who shared Tacfarinas’ desires. The new proconsul in the region, Publius Cornelius Dolabella, was taken by surprise by this renewed effort on Tacfarinas’ part. He wanted to retain the 9th legion in Africa, but was too afraid to contradict the orders of the emperor who wanted it back on the Rhine, likely fearing to have to explain to Tiberius just how bad the situation still was in Africa.

Having restored his army, Tacfarinas in 24 AD attacked the Roman town of Thubursicum, but was repulsed once more when Dolabella rushed the Roman army to the position. Tacfarinas once more fled into inhospitable terrain – but finally, the Romans recognized that he could not simply be left in this area to regather his strength. Dolabella recognized that there would be no end to the war while Tacfarinas lived, and that prevention of attacks was no longer sufficient – he had to be hunted down and either captured or killed.

Deploying his army in small units, assisted by using all his cavalry as scouts, Dolabella attempted to establish where Tacfarinas was hiding. He discovered him in a camp in Auzea (Sour El-Ghozlane, Algeria), a remote area bordered by a thick forest. Not having anticipated that the Romans would attempt to track him down, nor that they would find him if they tried, Tacfarinas did not post any sentries in the area, relying on the landscape to hide him and his men from danger.

He had made a devastating error.

Dolabella sent his cavalry and light-armed infantry through the woods by night, surrounding Tacfarinas’ camp.

At daybreak they launched an attack, catching the Africans by surprise and making it impossible for them to mount an effective defense. Many were slaughtered, not least as the Roman soldiers were in no mood for mercy after seven years of humiliation and defeat at the hands of this band – surrenders and pleas for mercy fell on deaf ears. Tacfarinas himself was surrounded and, recognizing the futility of his position and the tortures likely to come in captivity, threw himself onto the spears of the attacking Romans, ensuring that he died in the battle.

The insurrection was finally over.

As Rome had hoped, with the death of Tacfarinas the insurrection collapsed. No one tried to take over as the new leader of the rebels. Instead, the survivors drifted away to make what they could of the rest of their lives. The province immediately came under tighter Roman control, with tax registration of the entire region launched almost immediately afterward. Most of the lands used for pasture by the indigenous population were turned to grain production, and the tribes involved were likely permanently excluded from their traditional grazing grounds.

The Musulamii, Tacfarinas’ tribe, were never heard from again in the Roman historical record.

Tacfarinas had taught Rome a valuable lesson in Africa. Their initial conventional warfare responses to the irregular tactics employed by the insurrection had proved inadequate, failing to have any significant effect on Tacfarinas’ army. They were unable to mount an effective defense against the hit-and-run attacks used by the enemy, leading to significant economic losses across the region as well as a generalized destabilization of Roman interests in the area.

On the rare occasions where over-confidence led Tacfarinas to engage in more conventional warfare, the Romans prevailed. Rome seriously underestimated the manpower that Tacfarinas could draw on, wrongly judging that the rebel forces would tire of the conflict before the Romans did. Rome also failed to recognize the degree to which Tacfarinas was an almost talismanic figurehead. Three different Roman commanders in the region felt that they had ended the war when they inflicted a defeat on the Africans, but each success proved to be short-lived – not least because each left Tacfarinas alive to fight another day. It was only with the appointment of a commander who decided to adapt the tactics used by the rebels to chase them down into their hiding spots that the insurrection could finally be ended.

Rome had learned that sometimes to defeat the enemy, you had to fight on their level. Over time, irregular tactics would become increasingly used in the suppression of provincial rebellion.

Dr. Jo Ball is a University Teacher and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Liverpool. Her research interests include the archaeology of Greek and Roman battle, insurgency in the Roman world, and Roman combat psychology. She has just completed her first book, The Life of Publius Quinctillius Varus: The Man who Lost Three Legions in the Teutoburg Forest (2023, Pen & Sword Military), and can often be found lurking on Twitter (@DrJEBall ).

Contact the editor: oliver@thewarzone.com