One of the great strengths of the Roman army was its ability to evolve over time — tactically, strategically, and technologically. Anything that could give its soldiers an extra edge on the battlefield was enthusiastically embraced, and as the enemies they fought changed over time, so too did the kit of the typical infantry soldier.

The gladius sword was a perfect example of this — but it too was abandoned once it no longer offered the advantages in combat it once had, in favor of the long-bladed spatha sword. The evolution of the Roman infantry sword weapons reveals a lot about the responsive and adaptive nature of Roman warfare over time.

The gladius

In the modern day, the short-bladed gladius is the archetypical sword type of the Roman army, favored across the board from screen depictions to reenactment groups. So ubiquitous has it become that it is almost difficult to imagine a Roman soldier without his gladius at his side, perfect for stabbing at the enemy from the front line on the battlefield. However, it was not the first, nor the only, sword used by the Roman infantry over its 900 years of existence.

The earliest Roman armies emerged around the mid 6th century BC onwards, when Rome was just one Italian city-state among many. the period before the 4th century BC is very problematic in terms of historical reliability, it should be noted. Prior to this, the Roman military capacity was likely limited to tribe-based war bands. The army was not made up of professional soldiers. Men levied for campaigning seasons when required, with the army dominated by heavy infantry, with a smaller supporting contingent of cavalry.

At this early stage, there was no distinctive ‘Roman’ sword. Instead, soldiers likely adopted the same equipment used by Ancient Greek hoplites. This took the form of a short iron sword, typically 18-24 inches, known as a xiphos — a double-edged, straight, one-handed blade whose overall design likely dates back to the Bronze Age. The xiphos sword was the preferred Roman infantry blade for at least two centuries.

The Roman adoption of the xiphos suggests that their preferred fighting style in this early period was similar to that of the Greeks. Swords were predominantly used to thrust at the enemy on the front line of the battlefield, rather than in open-space fighting or one-to-one combat. It was a weapon for an organized army that fought in tight formation, as the Roman legions did. The xiphos served the early Roman army well for more than two centuries. However, it would eventually become outdated, and would be replaced with what is probably the most iconic Roman sword — the deadly gladius.

Adopting a Spanish blade

Although the gladius would become intrinsically connected with the Roman army, the sword’s origins lie elsewhere. It was actually developed by the Celtiberian population of Hispania (the modern Iberian Peninsula, Spain/Portugal). The Romans faced the gladius in battle during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), when it was wielded by Celtiberian soldiers in the service of the Carthaginian army. The Romans saw that the sword was equally effective at both thrusting and slashing attacks, making it a more adaptable weapon than the xiphos.

The sword was rapidly adopted by the Roman army — probably while the Second Punic War was still being fought — and became known as the gladius Hispaniensis, or ‘Hispanic-type sword’. It was roughly the same length as the xiphos, initially 24-27 inches, and was also a double-bladed sword that could be wielded with one hand. It could be integrated into Roman military use without a significant change to customary battlefield operations. It was made of steel rather than iron, making it a higher-quality blade. The gladius was also simpler to manufacture and could be made from a single piece of steel, with a steel crosspiece and wooden hilt added to make it easier to wield.

The adoption of the gladius Hispaniensis proved to be a wise decision for the Roman army. Within a few decades, its superior technology provided it with both a military and psychological advantage on the battlefield. The Roman historian Livy, for example, describes the wounds which Roman soldiers were able to inflict with this new weapon; including the disembowelment of foes as well as the severing of their limbs and splitting apart of their necks or heads. Historical descriptions of the damage caused by the gladius have been backed up by archaeological discoveries at several sites in Spain (Cerro de la Cruz, Valencia), where mutilated human remains graphically illustrate the damage this weapon could inflict.

For enemies used only to puncture wounds caused by spears and arrows, the damage that could be caused by the gladius must have been horrifying — and the Romans did not shy away from using it to full effect. A highly effective weapon had now clearly met an army brutal enough to wield it appropriately. From there, it would become the sword of choice for the Roman army for more than four hundred years.

So popular was the gladius that it is depicted on many military tombstones, where the deceased was wealthy enough to include a portrait on his stone, more frequently than any other Roman weapon. It was not just soldiers who loved the blade. Small wooden toy versions have been found, most notably from the fort of Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall located in modern-day northern England, perhaps given to young boys to encourage them to become soldiers in later life.

A continuing evolution – the Mainz gladius

The nature of Rome’s army changed at the end of the 1st century BC, with the coming of the Imperial period after the creation of the Imperial regime by the first Roman emperor, Augustus. He replaced the military conscription system of the Republican era with a professional army, in which soldiers would enlist for a fixed period of at least 16, and later 20, years if they were citizens, or 20, and later 25, years if they were non-citizens. These enlistment periods were much longer than the typical Republican service of six years, enabling soldiers to become ever more proficient in fighting.

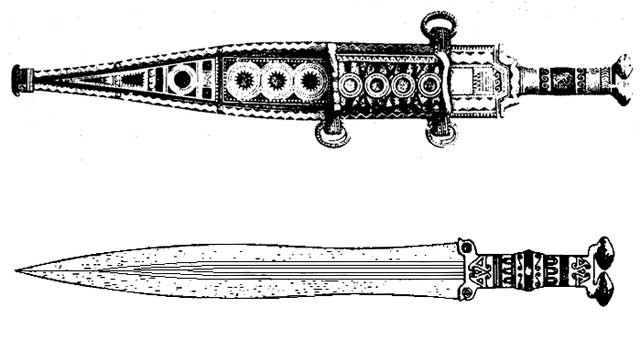

The Romans may have found their perfect sword in the gladius, but that did not mean there was no need for improvement over time. By the end of the 1st century BC, the Hispaniensis form had given way to a new variant of gladius, known today as the Mainz type, named for the German city where the type was discovered, and probably mass-produced in antiquity.

This type of gladius was shorter than its predecessor, with a typical blade length of 19-21 inches and was particularly suited to the new types of warfare that Rome was facing at the time. In previous centuries, the Roman army had mainly fought pitched battles against other organized armies, fielded by cohesive Mediterranean-based kingdoms or states. But by the late 1st century BC, Rome’s expansion had moved to northern Europe, where they faced more irregular conflict against tribal warrior bands. Pitched battles gave way to ambushes and skirmishes, often in difficult forested, marshy, or uneven terrain.

The Roman army had to adapt to these new military circumstances. Making the gladius blade shorter, and the sword lighter overall as a result, meant that they could operate more maneuverability, and still function effectively within the new types of terrain they were required to fight in. One Roman commander named Germanicus, for example, noted how well-suited the gladius was to fighting in the forests and brushwood of northern Europe, arguing to his men that it gave them a distinct advantage.

Although the swords were functional items, there was still room for decoration, particularly on the scabbards. One great example of this is the so-called ‘Sword of Tiberius,’ which was excavated from the bed of the Rhine near Mainz, later donated to the British Museum. The sword’s scabbard also survives, decorated with a scene showing the emperor Augustus as the god Jupiter, being presented with symbols of military victory by his stepson and heir, the future emperor Tiberius. The ornate nature of its decoration led to it being identified as a prestige item, commissioned by or for an officer to commemorate a significant victory, but the discovery of fragments of similarly ornate scabbards elsewhere suggests that many soldiers may have had decorative scabbards — provided that they could afford them.

The Mainz gladius was used from 20 BC until at least the 40s AD, as examples linked to the 43 AD Roman invasion have been found in Britain. However, a new type of gladius was already beginning to appear by that point, one which would become the most popular of all the gladius forms.

The Pompeii gladius

By the mid 1st century AD, the Mainz type had been superseded in popularity by the Pompeii-type gladius, named as such by modern historians after four examples were found at the famous volcano-buried city. It was already in use by the time of the Boudican revolt in Britain in 60/61 AD, and use of the blade probably crossed over with the Mainz type before the latter became obsolete.

The Pompeii gladius continued the trend set by the Mainz type for shorter and lighter blades, measuring in at around 18-20 inches. It was also a much narrower blade than its predecessors, requiring 10-20 percent less iron to produce — a significant economic saving that also made the sword much lighter.

This gladius was especially suited to delivering thrusting wounds from a tight battle line. Military-themed relief sculptures from this period predominantly show soldiers in the battle line using their swords to stab at their opponents. These same depictions also suggest that many soldiers wore segmented armor on their sword-arm from this period, which would have protected a vital but previously vulnerable part of their body, while also encouraging them to favor low thrusting blows over wider slashing.

Gladiators also made use of the Pompeii gladius. It became the sword of choice for the fighter types who were armed with a blade. Gladiators showed the adaptability of the blade to fighting outside the confines of the battle line, although the devastating injuries that could be inflicted by it led to high casualties within the arena.

The rise of the long sword

The gladius served the Roman army well for centuries, but eventually reached a point where it no longer suited the type of warfare Rome was facing. By the 3rd century AD, the gladius was increasingly giving way to the spatha, a straight long blade measuring 20-31 inches.

The spatha was not a new sword to the Roman army, as such, having probably been used since the 1st century AD by auxiliary soldiers from northern Europe, particularly by cavalry soldiers who would benefit from its length and suitability for slashing down at infantry enemies, although auxiliary foot-soldiers may also have carried the blade during this period. But by the late 2nd century AD, the spatha was also being used as an infantry sword, suggesting a significant change to the nature of Roman warfare by this period.

There are no descriptions from antiquity about why the longer spatha came to supersede the gladius, and it is not clear even today. The greater length of the blade must have offered some new advantage in battle against the enemies Rome was facing. By this time, warfare was largely concentrated either in northern Europe, including new invasions by peoples making territorial incursions from east of the empire, such as the Goths, or within the empire itself over a succession of civil wars. Roman warfare was no longer dominated by small-scale skirmishes in inhospitable terrain, but once again required the fighting of large-scale battles against organized and capable enemies — including other Romans — who used both infantry and cavalry against them. The entire Roman approach to warfare had to change once more, as did the weapons they used to wage it.

Roman soldiers had by this point adopted defensive neckguards on their helmets, which required them to fight with a very upright stance, which likely suited the use of a longer blade. The writings of the 4th century AD historian Vegetius suggest that by his time Roman soldiers were more spaced out on the battlefield front line, which would again favor a longer blade — but was the spacing increased because the spatha was adopted, or the spatha adopted because the spacing had increased?

In this new warfare, a blade that still offered the ability to thrust or slash from the front line, but from a slightly further range, became more suitable than the gladius which required soldiers to come in very close to the enemy. The gladius became a sword used only by light-armed infantry, if at all. However, the spatha was not particularly effective with regard to sword-on-sword fighting, with excavations suggesting that they were prone to breaking if they clashed against another blade too often. One Roman historian also suggests they could be easily blunted by this action.

The Romans were the ultimate pragmatists when it came to military matters, adopting whatever martial technology gave them the greatest chance of victory on the battlefield. The evolution of the Roman infantry sword illustrates this perfectly. For a long time, the short gladius most suited their needs, taking inspiration from the Celtiberians, with the blade itself adapted over time to make it shorter and lighter. But in later centuries, the gladius left them vulnerable, and a new approach was needed, with infantry soldiers adopting the longer spatha that had previously only been used by cavalrymen.

It was this adaptability that made the Roman army the preeminent military force for so much of antiquity — soldiers were given what they needed to win battles, and for many centuries, they did just that.

Dr. Jo Ball is a University Teacher and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Liverpool. Her research interests include the archaeology of Greek and Roman battle, insurgency in the Roman world, and Roman combat psychology. She has just completed her first book, The Life of Publius Quinctillius Varus: The Man Who Lost Three Legions in the Teutoburg Forest (2023, Pen & Sword Military), and can often be found lurking on Twitter ( @DrJEBall).

Contact the editor: oliver@thewarzone.com