The Russian military appears to have emplaced Pantsir air defense systems on top of at least two different government buildings in Moscow, including the Ministry of Defense’s headquarters. The official reason for the apparent deployments is unclear, but Ukrainian forces have demonstrated their ability to conduct strikes at extended ranges using various types of drones. There could be other explanations, including this just being part of an ostensible exercise of some kind.

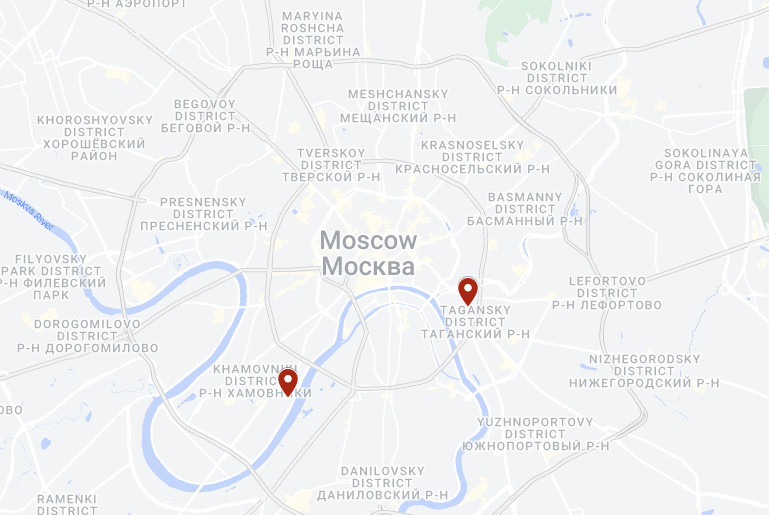

Multiple pictures and videos reportedly showing the rooftop Pantsirs began to emerge on social media earlier today, but it is not immediately clear when exactly they were taken. In addition to the one on top of the headquarters of Russia’s Defense Ministry, another looks to have been craned onto a building that is slightly closer to the city center and that Google Maps says belongs to the country’s Ministry of Education.

It is unclear what specific versions of the Pantsir system are seen in the imagery, but they appear to be variants with the improved search radar, referred to variously as SOTS or RLM SOC, on top. The radar, which is a rotating, mechanically-scanned array, is distinctive visually from earlier types used on Pantsir variants in that has two separate fixed-face antennas instead of just one.

Pantsir uses two radars, one to acquire targets and another to direct its command-guided missiles to intercept them. It is intended to primarily provide a point defense capability against various aerial threats, including fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, drones, and cruise missiles. It also has at least some ability to engage artillery rockets, mortar rounds, and bombs.

Most variants of the system are also armed with a pair of twin-barrel 30mm cannons, but versions have been offered with missiles only. The system can be mounted on various wheeled and tracked chassis, and a navalized type for use as a close-in weapon system exists, as well.

The SOTS/RLM SOC radar is said to increase the range at which targets can be detected and how many targets can be tracked at once, and how accurately they can then be engaged. This was reportedly a product of lessons learned from the less-than-stellar performance of earlier Pantsir types in Syria, especially against drones.

This is, however, not the most advanced configuration of Pantsir that has been seen to date. A variant that uses a more advanced active electronically-scanned array (AESA) search radar emerged in 2019.

Without knowing more, it is hard to say exactly what kind of defensive coverage Pantsirs on top of the Ministry of Defense headquarters, and the other building tied to the Ministry of Education, might be able to provide. The systems would offer protection in a ring around these sites and would have better overall fields of fire thanks to their elevated positions.

It is possible that additional Pantsirs or other air defense assets may now be positioned in or around Moscow, too. This would all be in addition to the substantial air and missile defense capabilities already protecting Russia’s capital.

The idea of positioning point defense systems like Pantsir around high-value and otherwise very sensitive locations as part of a larger integrated air defense network is certainly not unheard of. The U.S. military notably operates a number of Avenger air defense systems, which can engage various aerial threats with Stinger heat-seeking short-range surface-to-air missiles and .50 caliber M3P machine guns, in similar rooftop positions in Washington, D.C.

The Pantsir deployments could point to concerns about the potential for Ukrainian strikes targeting Moscow. Though the government in Ukraine is typically tight-lipped about the specifics, its forces have allegedly been responsible for a number of strikes inside Russia proper, including ones in December targeting an air base 300 miles from the border.

These strikes appear to have been conducted with various types of uncrewed aircraft drones, including Soviet-era jet-powered reconnaissance drones converted into weapons and commercially-available designs loaded with explosives.

In March 2022, shortly after Russia launched its all-out invasion of Ukraine, what appeared to be a Ukrainian Tu-141 reconnaissance drone with a warhead installed notably crashed in the Croatian capital Zagreb. This city is, at closest, around 340 miles from Ukraine. The shortest distance between Moscow and the Russian-Ukrainian border is around 286 miles.

Representatives of Ukraine’s state-run defense conglomerate Ukroboronprom claimed last week to have completed testing of a new strike drone design with a range of 1,000 kilometers (just over 620 miles). Reports about this system first emerged late last year.

Ukrainian operatives or anti-government partisans inside Russia could launch shorter-range armed drones, as well.

A demonstrated Ukrainian ability to hit targets deeper inside Russia, including in and around Moscow, could have significant operational implications. Destroying logistics, command and control, and other critical nodes within Russia proper could have very real impacts on battlefields in Ukraine. it could also force Russia’s military to redeploy critical air and missile defense assets back inside its borders.

In addition, Ukrainian forces have appeared for months now to be looking for ways to retaliate more and more directly against Russia in response to strikes inside their country, in general. The Russian military has been striking targets across Ukraine for almost a year now and continues to do so. This includes indiscriminate strikes on the capital Kyiv and other cities since all-out fighting began nearly a year ago. Just this past weekend, dozens of Ukrainian civilians died and more were wounded when a Russian air-launched Kh-22 cruise missile struck an apartment building in the city of Dnipro.

All told, even a symbolic strike on a legitimate military target in Moscow, or somewhere nearby, could be a propaganda coup for the government in Kyiv. This, in turn, could prompt further criticism of how Russian President Vladimir Putin and his government are handling the war in Ukraine, which has already been building publicly.

In this context, it’s interesting to note that, in December 2022, Yuri Knutov, the director of the Museum of Air Defense Forces, said during an interview on state television that gaps had emerged in Russia’s domestic air defense networks due to the demands for those capabilities to support forces in Ukraine. Knutov further warned that this might open a door to a possible Ukrainian strike on Moscow.

The previous apparent Ukrainian drone strikes on targets inside Russia indicate that the country’s air defense networks have already had difficulties in detecting and tracking uncrewed systems. Drones, by their nature, can be difficult to spot and intercept, and the Pantsirs in Moscow would offer an additional final line of defense against them and other aerial threats.

There is the possibility that the deployment of Pantsirs in Moscow might be part of a propaganda effort of some kind on the part of the Kremlin or an attempt to create some kind of pretext for escalation against Ukraine or its international partners. Today, a number of Western countries pledged to send even more military aid to the Ukrainian armed forces and dramatically increase the scope of that assistance.

The forthcoming aid packages, which have already prompted new vague threats of retaliation from Russia, will reportedly include Ground-Launched Small Diameter Bombs (GLSDB). GLSDB will significantly increase the range at which Ukraine can reliably conduct precision strikes, as you can read more about here. GLSDBs, however, would not be able to reach Moscow from Ukrainian territory. The United States continues to decline requests to transfer Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missiles, which also do not have the range to hit the Russian capital from Ukraine.

Russia has, of course, also claimed, without evidence, in the past that the United States and other Western countries have been plotting direct attacks of various kinds against Russia in support of Ukraine. Earlier this month, Yevgeny Fedorov, a deputy of Russia’s Duma, the country’s parliament, made an entirely unsubstantiated allegation that the U.S. government was planning to strike Moscow and was the actor actually responsible for other previous strikes inside Russia.

The apparent installation of Pantsir air defense systems on top of government buildings in Russia’s capital could turn out to just be temporary as part of an exercise or some other kind of military demonstration. In October 2022, Russia’s Federal Protective Service, or FSO, conducted an ostensible drill in Moscow that also turned heads on social media and prompted initial speculation that a coup or counter-coup might be in progress.

It remains to be seen what, if anything, Russian officials have to say about the apparent deployment of the Pantsirs on top of buildings in Moscow. Whatever the official reasoning might turn out to be, it may still not inspire confidence in Russian air and missile defenses amid the growing threat of Ukrainian strikes inside the country.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com