Ukraine’s next long-range precision strike weapon could be the Ground-Launched Small Diameter Bomb, or GLSDB, with the Pentagon now apparently considering a Boeing proposal to supply Kyiv with the munition. The recently developed GLSDB, an adaptation of the widely used air-launched Small Diameter Bomb, or SDB, has not previously found a customer but would provide a significant boost to Ukraine’s capacity to strike in Russian rear areas.

The Reuters agency reported today that the U.S. Department of Defense is weighing up transferring an undisclosed number of GLSDBs to Ukraine, to meet that country’s insatiable demand for weapons, especially those that can reach targets far behind Russian lines with great precision. They have a unique ability to undermine Moscow’s ability to sustain its invasion.

According to the same report, if approved, the first GLSDBs could be delivered to Ukraine as early as spring 2023. That would mean the weapons would likely be available for a renewed spring offensive — or counter-offensive — depending on how the battle lines change over the critical winter months.

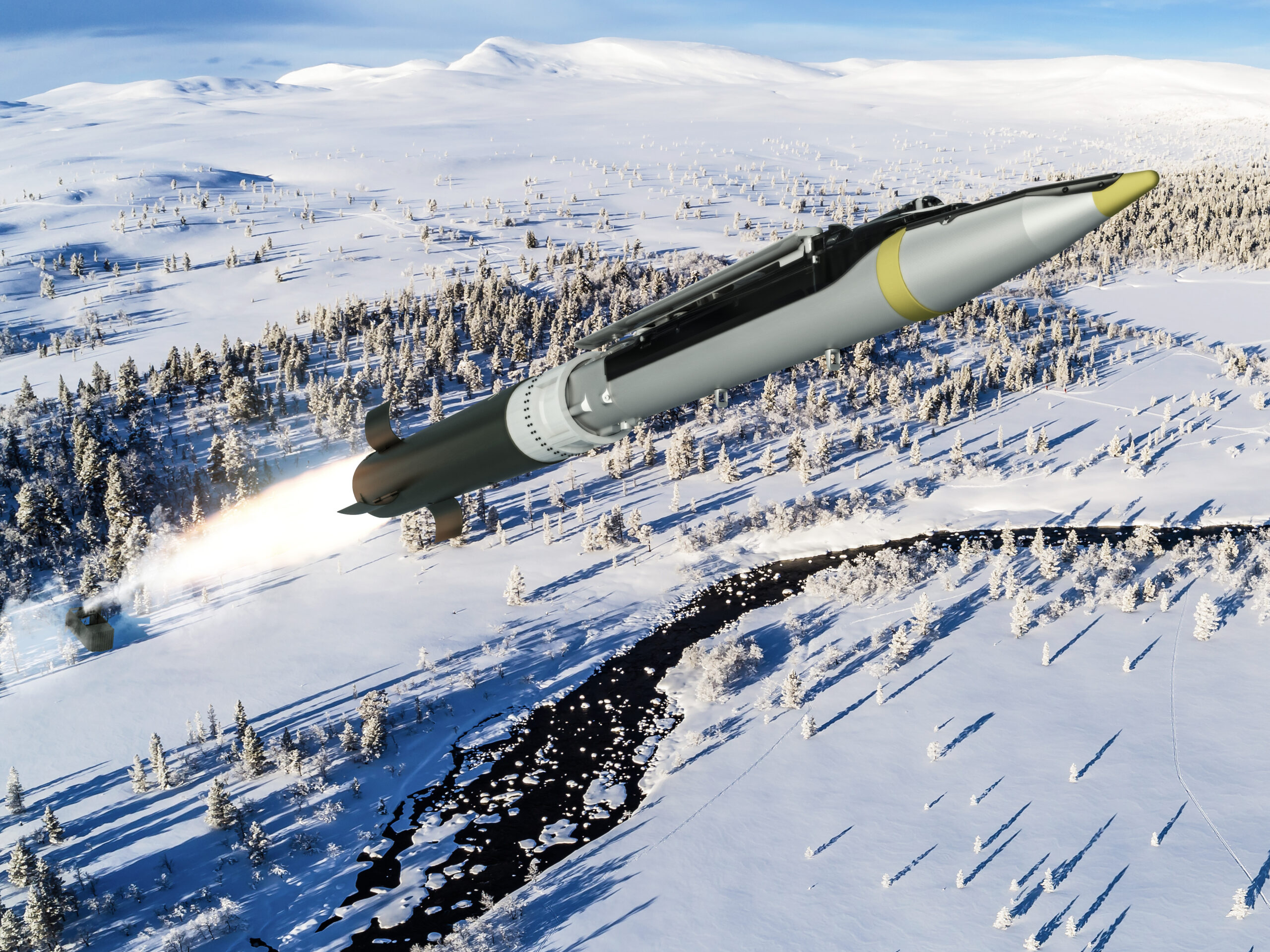

Developed by Boeing in partnership with Saab of Sweden, each GLSDB round is a combination of two existing systems, the air-launched 250-pound GBU-39/B SDB with its pop-out wing set and the rocket motor from the 227mm-caliber M26 artillery rocket. The M26 is among the rocket types that can be fired from M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS), and variants thereof, and the M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS). HIMARS is famously already in use with Ukraine, as are its tracked stablemate that fires the same ammunition, the M270 MLRS.

Propelled by the M26 rocket motor for the initial boost/loft phase, the GLSDB’s wings are then deployed and it flies unpowered, as a glide bomb. It uses the GBU-39/B’s existing inertial navigation system and embedded GPS to guide it to its target. That guidance system not only ensures accuracy to within 3 feet, according to Saab, but is also resilient to electronic warfare jamming, something that is of particular concern in the Ukrainian conflict.

The GLSDB has also been offered with the Laser SDB, which adds a laser seeker to the guidance package, allowing moving targets, including maritime ones, to be engaged. However, with the SDB II, or GBU-53/B StormBreaker already on the horizon, the Laser SDB has apparently seen only limited production, and it’s less likely to be available for supply to Ukraine.

While the air-launched SDB was already developed with low collateral damage in mind, the ground-based GLSDB application is said to deliver enough firepower to destroy a range of targets, from soft-skinned vehicles all the way up to hardened bunkers. The combined penetrating and blast-and-fragmentation warhead is triggered by a programmable electronic fuze. This means the weapon can be set to detonate above the ground or with a delay for deep penetration. There is also a dedicated low-collateral damage variant of the SDB, too, but like the LSDB, there are probably fewer of those in inventory to rapidly transfer.

Unlike most artillery rockets and ballistic missiles, the GLSDB doesn’t follow a ballistic path, meaning it can engage targets from a variety of angles and trajectories. In its promotional literature, Saab boasts of GLSDB being “launchable from hidden or protected positions to avoid detection,” making it less susceptible to counter-battery fire.

The GLSDB has a range of around 94 miles, or 150 kilometers, which is still well short of the longer-range versions of the ATACMS missile, which can engage threats out to 186 miles (300km) depending on the variant, and which is a much heavier weapon delivering a much bigger punch. The United States has so far proven resistant to supplying ATACMS, which would represent a major escalation in arms transfers and allow Ukraine to make precision strikes deep into Russian territory.

However, the GLSDB still has significantly greater reach than the longest-range 227mm artillery rockets currently available for the M270 MLRS and the M142 HIMARS. These can fire the M30 (submunition warhead) and M31 (unitary warhead) precision-guided rockets from podded launchers, and these can hit targets out to around 43 miles (70 kilometers).

The GLSDB also offers a good deal of versatility in that it can be fired from a number of different launchers, including the M270 MLRS tracked launcher and the M142 HIMARS which is based on a wheeled chassis. The podded launchers used by these systems could potentially be loaded with a mix of artillery rockets and GLSDB rounds. On the other hand, these same pods can accommodate only a single ATACMS missile.

So far, GLSDB has been demonstrated with a six-round launcher, although the “launcher-independent” nature of the munition means it can be fired from other interfaces, too. These include a modular launcher based on a purpose-built 20-foot ISO container, which can be mounted on a flatbed truck, a format that has been offered in the past to Finland, as seen in the tweet below.

All in all, the GLSDB appears to be a potentially very useful solution to meeting Ukraine’s demand for long-range precision firepower – not only in terms of its overall capabilities but since the M26 rockets and the GBU-39/B SDB are widely available in the stockpiles of the United States and other allies (a key selling point). The Boeing proposal would see the components for Ukraine’s GLSDBs drawn mainly from existing U.S. stocks.

Indeed, with the GBU-39/B having been developed for the kinds of low-intensity warfare that was prevalent in the Middle East and Afghanistan in the previous two decades, there’s an argument that at least a portion of these munitions would be better served being converted to GLSDB for use in Ukraine.

The overall cost of the GLSDB is also an attractive factor, with a single GBU-39/B priced at around $40,000. In contrast, a Guided MLRS round costs approximately $100,000.

The major question, perhaps, is the ability to produce the GLSDB in the kinds of volume that Ukraine requires. Reuters says that deliveries from spring 2023 would involve “a low rate of production” and, with no other customers so far for what is still a fairly new product, manufacturing the GLSDB, even making use of existing components, could take time to ramp up.

Boeing and Saab would no doubt be keen to see GLSDB exposed to combat against a high-end opposition in Ukraine, which would not only prove its capabilities but also bring it to the attention of other possible export customers. Central and Eastern European nations, in particular, are currently recalibrating their armed forces to meet the changing Russian threat, and long-range strike is a key area of concern.

However, the process of starting series production of GLSDB is not entirely straightforward, with Reuters reporting that Boeing’s proposal involves a price discovery waiver. This would ensure the manufacturer is exempt from the kind of procurement review that would normally accompany a Pentagon arms purchase, to ensure that it’s getting the best value for money. Ramping up production to the required level would also require “at least six suppliers to expedite shipments of their parts and services to produce the weapon quickly,” Reuters confirms.

Interestingly, it has been widely assumed that Boeing was responsible for helping to rapidly deliver a shore-launched Harpoon capability to Ukraine. That suggests some potential existing engagement between Boeing and the Pentagon on rapidly supplying capabilities to Kyiv, which could be leveraged here, too.

It remains to be seen if and when GLSDB ends up in Ukraine, but there’s no doubt that the country’s demand for advanced weapons frequently outstrips what’s currently readily available. At the same time, the continued flow to Ukraine of arms from the United States and other nations means that existing munitions stocks around the world are being depleted, with the ability of industry to backfill repeatedly coming into question.

If approved, GLSDB would give Ukraine a semi-readily available weapon that can more than double its standoff precision strike range capability, compared to the current MLRS/HIMARS. At the same time, it still lacks the punch and the range of ATACMS, making it politically more viable. It also can use existing launch infrastructure and tap into existing rocket motors and SDB stocks. Just as significantly, its range would increase the options for Ukraine to hit deep into Crimea, for instance, which has already been subject to long-range strikes by different means.

With all that in mind, GLSDB could well make a lot of sense for Ukraine and, if fielded, its success on the battlefield is likely to lead to more interest in what should be a relatively low-cost and highly versatile long-range strike weapon.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com