Russia says it has formally linked its air defenses in Syria together with those of the regime of Bashar Al Assad. This could potentially limit the U.S. military’s ability to support its local partners fighting ISIS, increases the risk of a dangerous confrontation, and just add yet another layer to an ever more complicated situation on the ground.

Chief of Staff and Deputy Commander of the Russian Aerospace Forces Major-General Sergey Meshcheryakov made the announcement during a press roundtable at the Army-2017 International-Military Technical Forum on Aug. 25, 2017, according to state-run media outlet TASS. The event at the Patriot Expocentre in the Moscow Region is an annual military trade show and this year also includes a pavilion dedicated to the Kremlin’s intervention in Syria.

“Today, a unified integrated air defense system has been set up in Syria,” Meshcheryakov said. “We have ensured the information and technical interlinkage of the Russian and Syrian air reconnaissance systems. All information on the situation in the air comes from Syrian radar stations to the control points of the Russian force grouping.”

Russia’s air defense assets in Syria include S-300 and S-400 long-range surface-to-air missiles, as well as Pantsir-S1 short-to-medium range air defense systems. The bulk of these weapons are situated at Hmeimim Air Base south of Latakia, which also hosts Moscow’s air contingent, including advanced Su-27SM3 Flanker and Su-35S Super Flanker fighter jets and Su-34 Fullback multi-role combat aircraft.

Meshcheryakov claims that his troops can hit targets nearly 250 miles away and at altitudes above 100,000 feet. This maximum range theoretically gives Russia the ability to engage targets nearly anywhere in the country, as well as over neighboring Turkey and Lebanon.

When linked together with whatever additional radar coverage Assad’s forces might be able to provide, the systems present a significant threat to anyone flying over the country, including the U.S. military and its coalition partners. At the Army-2017 expo, the Syrian operations pavilion had a display that suggested the short-range Pantsir-S1s had already been very active in the country, possibly even engaging American or other coalition drones.

Though unconfirmed, the Russians claimed the systems had knocked down incoming rockets, small unmanned aerial vehicles, and surveillance balloons, according to one placard. On June 17, 2017, one of these anti-aircraft weapons reportedly knocked down an RQ-21A “Integrator” near their naval base at Tartus. Also known as the Blackjack, this system is in service with U.S. special operations forces.

But whether these reports are accurate or not, Russia’s decision to deploy its air defense elements have already been a concern, as evidenced by a number of heavily redacted weekly intelligence summaries from the U.S. Air Forces Central Command’s Coalition Intelligence Fusion Cell, which the author previously obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. These reports show, unsurprisingly, that this office at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar – which also hosts the so-called “hotline” with Russian forces in Syria – routinely tracks reports of “air-to-air encounter and SAM events affecting Coalition aircraft” and other threats to the aerial campaign against ISIS, including at least one report of “GPS jamming.”

Now that the Russians are connected directly to their Syrian counterparts, the presence of their air defense assets can only give the American-led coalition additional pause when planning operations in the country against terrorists in Syria. It adds new possibilities for a confrontation between U.S.-supported forces, or the U.S. military itself, to rapidly escalate into an even more dangerous situation, too.

Already this year, American multi-role combat aircraft have shot down

two Iranian drones and a Syrian Arab Air Force Su-22 ground attack aircraft that were menacing U.S.-supported Syrian groups. This highlighted the increasing danger U.S. troops faced while operating in close proximity to the Syrians and their allies, who are openly hostile, at least rhetorically, to their very presence in the country.

We at The War Zone have noted for some time that these and other incidents had pushed Russia and Syria toward even closer cooperation, which in turn could only limit the flexibility of U.S. forces and put them in riskier situations. After the United States’ pinprick attack at Shayrat Air Base in Syria in April 2017, following a reported chemical attack on civilians, Assad had already relocated most of his own Air Force behind the protective umbrella of Russia’s air defenses.

The Russia-Syria integrated air defense arrangement, which may have existed in some form before on an ad hoc level, only reinforces this status quo and makes it more difficult for the United States to apply pressure on Assad now and in the future. It has probably all but eliminated any meaningful discussion of imposing a no-fly zone against Assad’s air force in the near term. The Russians have already been able to dictate the prosecution of much of the conflict in western Syria.

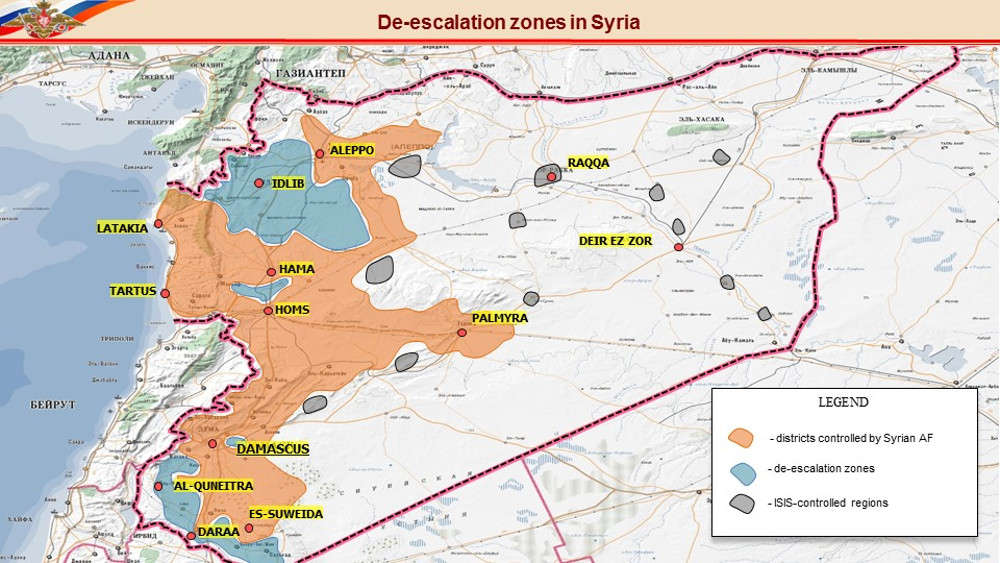

The Kremlin has also pushed to set up “de-escalation zones,” together with Iran and Turkey, which that benefit their collective interests. Earlier in August 2017, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov told members of the press after a diplomatic meeting in Cambodia that he expected the safe area in Idlib, along the border with Turkey, to come into effect soon.

The United States has already agreed to support some portion of these ceasefire deals in southwestern Syria, along the borders with Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon. On Aug. 23, 2017, the U.S. State Department announced that it would establish a shared monitoring office with Russian and Jordan personnel in the Jordanian capital Amman.

It is unclear how any of this increasing cooperation, especially the new Russian-Syrian air defense deal, will necessarily impact the American-led campaign against ISIS in Syria. At present, U.S.-supported Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) are in the midst of a pitched battle to eject the terrorists from their de facto capital in Raqqa.

There are indications that this relationship may be increasingly strained, though. Earlier in August 2017, an SDF spokesman told Reuters that American forces would remain in Syria after the defeat of ISIS, an assertion that both the Pentagon and the U.S. State Department subsequently refuted. Still, the U.S. government has yet to clearly articulate how it intends to transition its activities in the country if and when it deems to the terrorists are no longer a threat.

Needless to say, the situation in Syria is complex and often fluid. However, the Russians and the Syrians seem to be intent on making sure that American involvement in the country stays is limited and ends as soon as possible.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com