A video went viral this week depicting a cuirass in a museum with a massive hole ripped directly through its chest. Based on the condition of the armor, the massive wound that resulted is hard to fathom in terms of severity. While people mostly wanted to debate the caption of the video on Twitter, which stated the soldier wearing the armor was “wounded,” historians have since chimed in on social media to provide a wealth of knowledge about the armor’s former owner, his life before the battle, and how he likely died at Waterloo. Here’s the whole story.

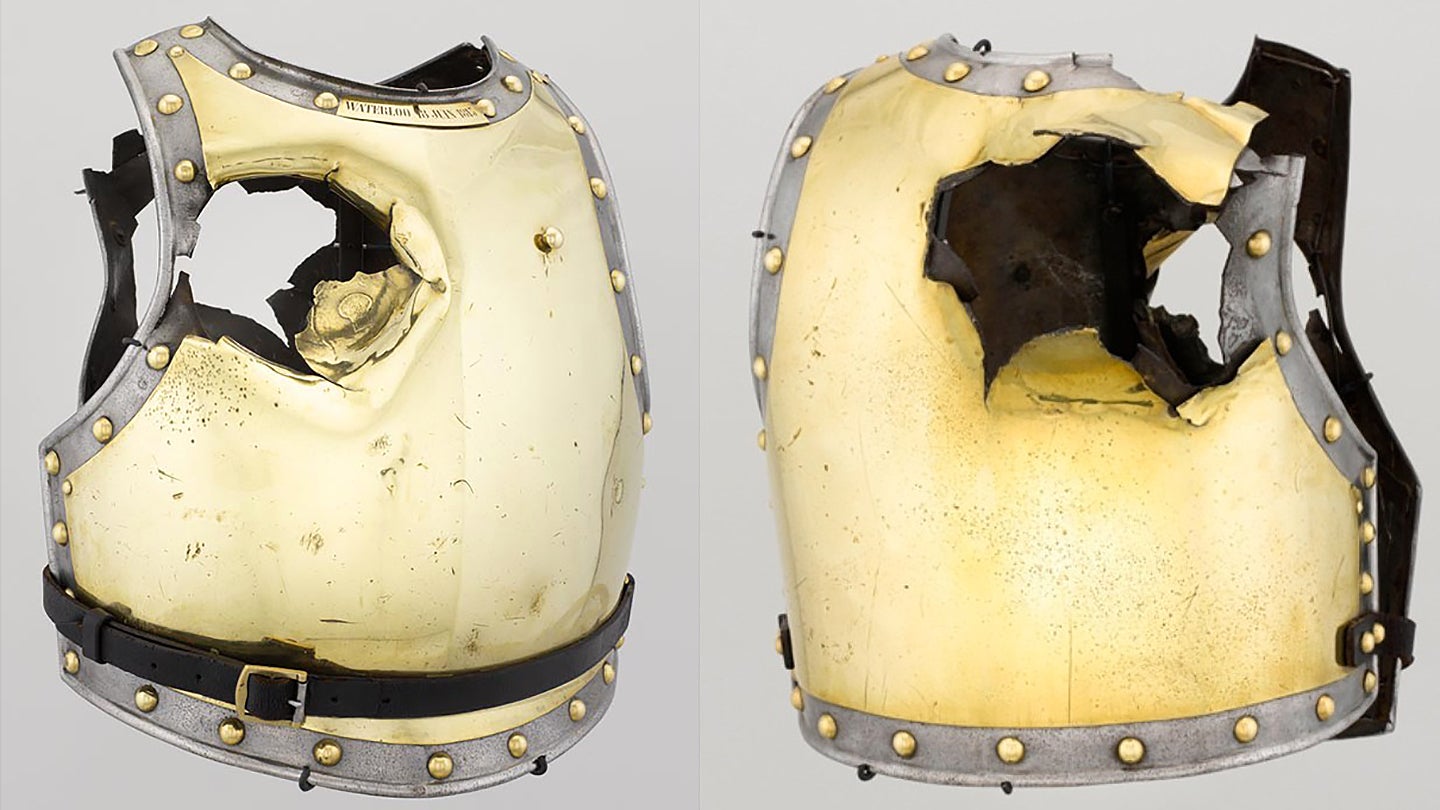

The video, shared by Twitter user @TheFigen, shows a nearly 360-degree view of a brass and iron cuirass, or breastplate, worn by a soldier who fell at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. A grapefruit-sized entry hole is punched through the breastplate, while the backplate is violently ripped open by the exiting cannonball, opening it up nearly all the way across the other side of the soldier’s back.

The cuirass is housed in the Musée de l’Armée (The Army Museum) in Paris, which houses a large collection of French military artifacts including uniforms, soldiers’ personal belongings, and weapons spanning from the 13th century to World War II. The cuirass is part of the museum’s sizeable Napoleonic war collection, which the facility calls “particularly remarkable.”

According to Dr. Tony Pollard, a professor of conflict history and archeology at the University of Glasgow who has conducted fieldwork at Waterloo, the cuirass in the viral video was worn by François-Antoine Fauveau, a 23-year-old Caribinier a Cheval, or heavy cavalryman, serving in the Napoleonic Army’s 4th company, 2nd Carabinier Regiment. These carabiniers wore brass and iron armor over white tunics, with white leather riding pants and knee-high riding boots. The carabiniers’ primary weapons were swords, but they also carried a pair of pistols and a carbine — a lighter, shorter-barrelled form of the infantry musket.

According to documents found on Fauveau after his death, the young man was a dairy farmer prior to the war and had a “long, freckled face with a large forehead, blue eyes, hooked nose, and a small mouth.” According to some accounts, the soldier was due to get married shortly before he was conscripted into Napoleon’s army. Pollard said Fauveau likely had less than seven days of military training before he was sent off to fight.

Fauveau’s time in the military would be cut short on June 18, 1815, at what would be the end of the Napoleonic Wars. On that date, self-proclaimed “Emperor of the French” Napoleon Bonaparte, having returned from exile from previous defeats, marched an army of around 72,000 soldiers to the village of Waterloo, south of Brussels in an attempt to catch British and allied forces, under Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, off guard. A brutal, day-long battle ensued, ending only after Prussian troops arrived late in the evening to flank the French, allowing British troops to drive Napoleon’s forces from the field. Some estimates put the total number of casualties at over 30,000 for the French forces and over 20,000 for the British and Prussian forces.

The heavy casualties on both sides were largely due to advances in artillery weapons that occurred throughout the 18th century. The Industrial Revolution made it much easier for forces on both sides to quickly manufacture weapons, and advances in heavy weaponry, largely driven by French innovations, made it easier to quickly deploy artillery on the battlefield or move it from location to location.

Unfortunately, Antoine Fauveau would be one of the casualties struck down by a nine-pound cannonball during the Battle of Waterloo. Hopefully, the incredible damage inflicted to his breastplate meant he did not suffer long after the cannonball tore through his torso.

While it can be easy to lose sight of the human cost of historical and ancient battles due to the distance we have from them, artifacts like this devastated cuirass help us remember there was a person behind each casualty figure and clearly spell out the brutal reality of Napoleonic warfare.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com